John Boultbee (1753–1812) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of British art, particularly within the specialized genre of animal and sporting painting. Flourishing in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a period often dubbed the "Golden Age" of British sporting art, Boultbee carved a niche for himself with his sensitive and anatomically astute depictions of livestock, horses, and rural scenes. His work not only captured the aesthetic appeal of these subjects but also reflected the profound agricultural and social transformations sweeping across Georgian England.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Osgathorpe, Leicestershire, in 1753, John Boultbee emerged from a region deeply rooted in rural traditions and agricultural pursuits. This environment undoubtedly shaped his early sensibilities and provided a rich source of inspiration for his future artistic endeavors. While details of his earliest training are somewhat scarce, it is widely accepted and documented that Boultbee benefited from tutelage under two of the era's most eminent artists: Sir Joshua Reynolds and George Stubbs.

His association with Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), the leading portrait painter of the day and the first President of the Royal Academy of Arts, would have provided Boultbee with a strong foundation in draughtsmanship, composition, and the sophisticated handling of paint. Reynolds was renowned for his ability to capture the character and status of his sitters, often imbuing them with a sense of dignity and classical grace. While Boultbee would primarily focus on animal subjects, the principles learned from Reynolds regarding observation and representation were undoubtedly transferable.

Perhaps even more formative for Boultbee's specific career path was his time as a pupil of George Stubbs (1724–1806). Stubbs was, and remains, the preeminent animal painter of the period, celebrated for his unparalleled understanding of equine anatomy, derived from years of meticulous dissection and study. His paintings of horses, such as the iconic "Whistlejacket," set a new standard for realism and scientific accuracy in animal art. Learning from Stubbs would have exposed Boultbee to rigorous anatomical study and the techniques required to render animals with lifelike precision and vitality.

The Boultbee family itself had artistic inclinations. John's brother, Thomas Boultbee (c. 1747–c. 1804), was also a painter, specializing in similar subjects, and the two brothers sometimes collaborated or worked in a similar vein, occasionally leading to confusion in attributions. This familial artistic environment would have further nurtured John's talents.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

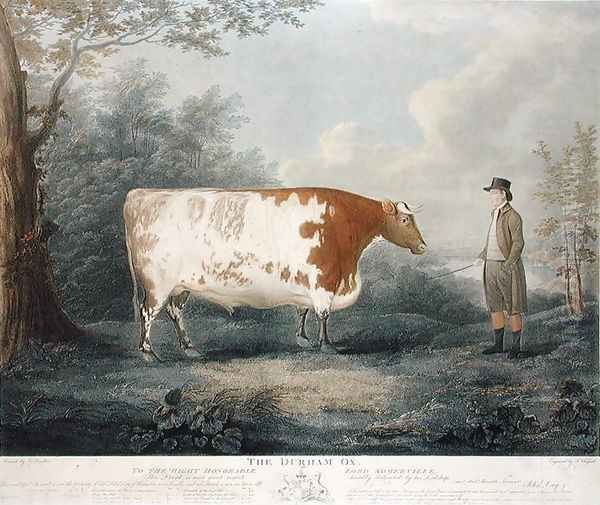

John Boultbee's artistic style is characterized by a robust realism, a keen eye for anatomical detail, and a sympathetic portrayal of his animal subjects. While influenced by Stubbs's scientific approach, Boultbee's work often possesses a slightly softer, more pastoral quality. He excelled in capturing the individual character of the animals he painted, moving beyond mere representation to convey a sense of their presence and, in the case of prized livestock, their economic and agricultural importance.

His primary thematic focus was on the depiction of horses and, notably, cattle. This was an era of significant agricultural advancement in Britain, often termed the Agricultural Revolution. Landowners and innovative farmers like Robert Bakewell of Dishley Grange, Leicestershire, were pioneering new breeding techniques to improve livestock. Boultbee became closely associated with this movement, receiving commissions to paint these prize animals. His portraits of selectively bred Longhorn cattle, for instance, served not only as works of art but also as records of agricultural achievement and status symbols for their owners.

Boultbee's compositions often place his animal subjects in serene, naturalistic landscapes, typically characteristic of the English countryside. These settings, while sometimes idealized, contribute to the overall harmony of his works and provide context for the animals depicted. He paid careful attention to the textures of fur, hide, and foliage, demonstrating a skilled handling of paint to achieve verisimilitude. His palette was generally naturalistic, employing earthy tones and subtle gradations of light and shade to model form.

Beyond individual animal portraits, Boultbee also painted sporting scenes, though he is perhaps less prolific in this area than some of his contemporaries. These works would have included hunting scenes or depictions of racehorses, popular themes among the landed gentry who were his primary patrons.

Key Patrons and Commissions

A significant aspect of John Boultbee's career was his connection with prominent figures in the agricultural world. His proximity to Leicestershire, a hub of breeding innovation, brought him into contact with influential agriculturalists. Among the most notable was Robert Bakewell (1725–1795), a revolutionary figure in livestock breeding. Bakewell's systematic methods of selective breeding led to dramatic improvements in sheep (the New Leicester breed) and cattle (improved Longhorns), and also influenced horse breeding.

Boultbee was commissioned to paint several of Bakewell's prize animals. These portraits were more than just artistic endeavors; they were a form of documentation and promotion for Bakewell's breeding programs. Paintings of magnificent bulls, hefty rams, or sleek horses served to advertise the success of these new breeding lines and the wealth and discernment of their owners. For Boultbee, such commissions provided a steady stream of work and aligned him with the progressive agricultural spirit of the age.

His patrons were typically country gentlemen, landowners, and prosperous farmers who took immense pride in their estates and their livestock. For them, a Boultbee painting was a testament to their success and a cherished depiction of their prized possessions. The demand for such paintings underscores the cultural importance of agriculture and animal husbandry in 18th-century Britain.

Notable Works

While a comprehensive catalogue of John Boultbee's oeuvre can be challenging to assemble definitively due to the passage of time and occasional attribution issues, several works and types of works are representative of his skill and focus.

His depictions of Robert Bakewell's Longhorn cattle are among his most recognized contributions. These paintings showcase the impressive physique of these selectively bred animals, emphasizing their bulk, musculature, and distinctive long, curving horns. One such example is "A Longhorn Bull," which captures the animal's powerful presence and the specific characteristics valued by breeders. These works are invaluable historical documents of early systematic livestock breeding.

Boultbee also painted Shorthorn cattle, another breed undergoing significant development during this period. His painting "A Shorthorn Bull, called 'Patriot', the Property of the Rt. Hon. Lord Yarborough" (though sometimes dates and specific attributions for famous named bulls like the "Durham Ox" or "Comet" can be complex and involve other artists like Thomas Weaver) exemplifies his ability to render these animals with precision and a sense of their individual importance. The famous "Durham Ox," for instance, painted by several artists including John Day and most famously by Thomas Weaver, epitomized the public fascination with such magnificent creatures, and Boultbee worked within this tradition of celebrating agricultural marvels.

Beyond cattle, Boultbee was an accomplished painter of horses. His equine portraits display a clear understanding of horse anatomy, likely honed under Stubbs. He painted various types of horses, from sturdy hunters to elegant carriage horses and thoroughbreds. These paintings would often include their owners or grooms, adding a narrative element and further emphasizing the bond between humans and these valued animals.

A particularly evocative and somewhat atypical work is "An oak tree struck by lightning in Dunham Park" (c. 1790s). This painting, held by the National Trust at Dunham Massey, Cheshire, depicts a dramatic natural event. It showcases Boultbee's skill in landscape painting and his ability to capture atmospheric effects. The splintered, ravaged oak stands as a powerful symbol, demonstrating his versatility beyond straightforward animal portraiture. The painting is noted for its accurate depiction of the explosive effect of a lightning strike on a tree, rather than just a burned appearance.

His works often appeared in exhibitions, including those at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, which helped to establish his reputation among a wider audience.

The Context: British Sporting Art and Contemporaries

John Boultbee worked during a flourishing period for British sporting and animal art. This genre, which had its roots in earlier European traditions, truly came into its own in Britain during the 18th century, fueled by the passions of the landed gentry for hunting, racing, and agriculture.

George Stubbs was undoubtedly the towering figure, but many other talented artists contributed to the richness of this field. Understanding Boultbee's place requires acknowledging his contemporaries.

Sawrey Gilpin (1733–1807) was another prominent animal painter, known for his romantic and often dramatic depictions of horses, sometimes in wild or exotic settings. He collaborated with other artists, such as Philip Reinagle (1749–1833), who himself was a versatile painter of animals, landscapes, and portraits. Reinagle was particularly noted for his sporting dogs and game birds.

Benjamin Marshall (1768–1835) emerged slightly later than Boultbee but became a leading figure in sporting art in the early 19th century. Marshall was celebrated for his vigorous and unsentimental portrayals of racehorses and hunting scenes, often capturing the raw energy and excitement of the sport. He famously stated that he discovered "many a man who would pay fifty guineas for a painting of his horse, who would not pay ten for a painting of his wife."

James Ward (1769–1859), a brother-in-law of George Morland, was another highly accomplished animal painter and engraver. Ward's work ranged from intimate studies of farm animals to grand, almost allegorical, depictions like his monumental "Gordale Scar." His style was often more dramatic and Romantic than Boultbee's.

Other notable names in this sphere include Henry Bernard Chalon (1770–1849), who became Animal Painter to the Prince Regent, and Abraham Cooper (1787–1868), known for his battle scenes as well as his sporting subjects. Jacques-Laurent Agasse (1767–1849), a Swiss painter who settled in England, also made significant contributions with his elegant and meticulously detailed animal portraits and genre scenes.

Earlier artists had laid the groundwork for this "Golden Age." Francis Barlow (c. 1626–1704) is often considered the "father of British sporting art," known for his detailed drawings and paintings of birds and animals. John Wootton (c. 1682–1764) and Peter Tillemans (1684–1734) were also key figures in the early development of sporting painting, specializing in equestrian portraits, hunting scenes, and race meetings.

Later, artists like John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795–1865) would continue the tradition, becoming immensely popular for his depictions of farmyard scenes and racehorses, including many winners of the St. Leger and Derby. Sir Edwin Landseer (1802–1873), while broader in his scope, also produced iconic animal paintings, often with a strong narrative or sentimental appeal, such as "The Monarch of the Glen."

Boultbee's work fits comfortably within this milieu. He may not have achieved the overarching fame of Stubbs or the dramatic flair of Ward, but his dedication to the accurate and sympathetic portrayal of agricultural animals, particularly cattle, gives him a distinct and important place. He catered to a specific, yet significant, demand, documenting a crucial aspect of British rural life and economic development.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

In the later part of his career, John Boultbee moved from his native Midlands. He is recorded as living and working in Liverpool for a period and eventually settled in Derby. He continued to paint, and his works were exhibited periodically. John Boultbee passed away in Derby in November 1812.

His legacy is primarily that of a skilled and diligent animal painter who made a valuable contribution to the art of Georgian England. His paintings are important not only for their artistic merit but also as historical documents. They provide visual records of specific animal breeds at a key stage in their development, offering insights into the agricultural practices and aesthetic preferences of the time. The portraits of Bakewell's Longhorns, for example, are tangible links to a pivotal moment in the history of livestock breeding.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, Boultbee's work is held in various public and private collections, including the National Trust, regional museums, and specialist agricultural collections. His paintings are appreciated by art historians, agricultural historians, and collectors of sporting art for their honesty, craftsmanship, and their quiet celebration of the British countryside and its animal inhabitants.

His dedication to capturing the essence of these animals, particularly the prized livestock that were symbols of national pride and agricultural prowess, ensures his enduring relevance. He was a master of his specific craft, contributing a distinct voice to the chorus of artists who chronicled the life and passions of rural Britain during a transformative era. John Boultbee's art reminds us of the deep connections between art, agriculture, and social history, offering a window into a world where the depiction of a prize bull or a fine horse was a matter of considerable importance and pride. His contribution, therefore, remains a noteworthy chapter in the story of British art.