Thomas Weaver (1774-1843) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the annals of British art, particularly renowned for his meticulous and dignified portrayals of livestock and rural life. Active during a transformative period in British agriculture and art, Weaver's oeuvre provides an invaluable visual record of the era's prized animals and the pride of the landed gentry and farming communities who commissioned his work. His paintings are more than mere animal portraits; they are documents of agricultural progress, social status, and a deep-seated connection to the land.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in 1774, Thomas Weaver emerged as an artist during a vibrant period for British painting. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw the Royal Academy of Arts, founded in 1768 under the presidency of Sir Joshua Reynolds, firmly establishing London as a major art centre. While grand historical narratives and society portraiture, championed by artists like Reynolds himself and his contemporary Thomas Gainsborough, often took centre stage, a growing appreciation for other genres, including landscape and animal painting, was also evident.

Details about Weaver's specific artistic training are not extensively documented, which was not uncommon for artists specializing in less academically lauded genres. However, it is clear he developed a keen eye for anatomical accuracy and a patient, detailed technique. He likely honed his skills through direct observation and possibly by studying the works of earlier masters of animal depiction, such as Francis Barlow from the 17th century, or more immediate predecessors like the celebrated George Stubbs, whose scientific approach to equine anatomy had set a new standard for animal painters.

Weaver's career began to flourish in the early 19th century. He started exhibiting his works at prominent London venues, including the Royal Academy and the British Institution. This exposure was crucial for an artist seeking patronage and recognition beyond a purely local sphere. His chosen specialty, the portrayal of prize-winning farm animals, resonated deeply with the agricultural advancements and the competitive spirit prevalent among landowners and breeders of the time.

The Golden Age of British Agriculture and Animal Portraiture

Thomas Weaver's career coincided with what is often termed the "Golden Age of British Agriculture." Innovations in land management, crop rotation, and, crucially, selective animal breeding led to significant improvements in livestock quality and productivity. Figures like Robert Bakewell had pioneered systematic breeding techniques in the latter half of the 18th century, leading to larger, more productive sheep, cattle, and pigs. This agricultural revolution was a source of national pride and economic strength.

Landowners and tenant farmers took immense pride in their improved breeds. Commissioning a portrait of a prize bull, a champion ram, or a particularly fine sow was a way to immortalize their achievements, advertise their stock, and display their status. Weaver stepped into this niche, providing a service that was both practical and prestigious. His paintings became visual testaments to the success of selective breeding, capturing the specific characteristics that made these animals champions.

Unlike some of his contemporaries who might have romanticized or overly dramatized their animal subjects, Weaver's approach was generally characterized by a straightforward, almost documentary realism. He paid close attention to the conformation, coat, and specific markings of each animal, ensuring an accurate likeness that would satisfy his discerning patrons. This fidelity to detail was paramount, as these paintings often served as records of breeding lines.

Weaver's Distinctive Style and Subject Matter

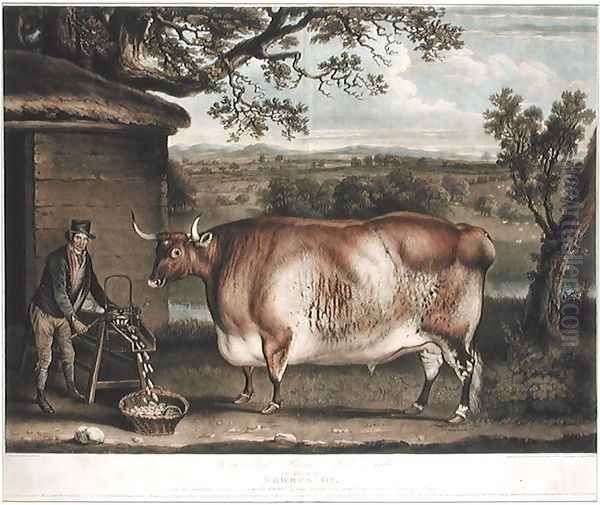

Thomas Weaver's paintings are typically characterized by their clarity, detailed rendering, and often a slightly formal, posed quality. The animals are usually depicted in profile or a three-quarter view, allowing for a full appreciation of their physique. They often stand in pastoral landscapes, sometimes with their proud owners or handlers nearby, further emphasizing the connection between human endeavor and agricultural success.

His subjects were diverse within the realm of livestock. He painted numerous prize cattle, such as the famous "Lincolnshire Ox" or the "Durham Ox," capturing their immense size and well-fleshed forms. Sheep, particularly breeds like the New Leicester or Southdown, were also frequent subjects, their dense fleeces and sturdy builds meticulously rendered. Horses, too, featured in his work, though perhaps less centrally than in the oeuvre of dedicated sporting artists like Ben Marshall or John Frederick Herring Sr., who focused more on racehorses and hunting scenes.

Weaver's human figures, when included, are often depicted with a similar attention to detail, their attire and demeanor reflecting their social standing and connection to the agricultural world. These "conversation pieces," combining animal and human portraiture, offer valuable insights into rural society of the period. The landscapes in his paintings, while secondary to the animal subjects, are typically well-observed, depicting the cultivated fields, hedgerows, and gentle hills of the British countryside.

Notable Works and Commissions

Among Thomas Weaver's most recognized works are his portraits of specific, named animals that had achieved fame in agricultural circles. "The Newbus Ox," painted in 1812, is a prime example, showcasing a magnificent beast that was a testament to breeding advancements. Another significant work is "The Ketton Ox," which, like many such paintings, was also reproduced as a print, allowing for wider dissemination and recognition.

The painting "A Prize Ram belonging to Mr. Coke of Holkham" exemplifies his skill in capturing the prized qualities of improved sheep breeds. Thomas Coke, later Earl of Leicester, was a leading agricultural reformer, and a portrait of his champion ram would have been a significant commission. Such works underscored the scientific and economic importance attached to livestock breeding.

Weaver also undertook commissions for portraits of landowners with their favorite animals or in rural settings. These paintings served a dual purpose: celebrating the individual's connection to their estate and their role in agricultural improvement, while also providing a dignified personal portrait. His ability to capture both animal and human likenesses with competence made him a sought-after artist in these circles. The demand for engravings after his paintings, such as "The Unrivalled Lincolnshire Heifer," further attests to their popularity and the public interest in these exceptional animals.

Context within British Art: Sporting Art and Romanticism

Thomas Weaver's work is firmly rooted in the tradition of British sporting and animal art, a genre that had gained considerable traction by the late 18th century. George Stubbs (1724-1806) was undoubtedly a towering figure whose anatomical studies and sophisticated compositions elevated animal painting. While Weaver may not have possessed Stubbs's profound scientific depth or classical compositional grandeur, he shared a commitment to accurate representation.

Other contemporaries in the field included Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807), known for his spirited depictions of horses and wild animals, often with a more romantic or dramatic flair. Ben Marshall (1768-1835) was a leading painter of racehorses and sporting scenes, capturing the excitement and elegance of the turf. James Ward (1769-1859), a versatile artist who also painted landscapes and historical subjects, produced powerful and often monumental animal paintings, sometimes imbued with a Romantic sensibility, such as his famous "Bulls Fighting."

While Weaver's primary focus was on the objective portrayal of agricultural animals, his career unfolded during the peak of the Romantic movement in Britain. The Romantic emphasis on nature, the sublime, and the individual experience found expression in the landscape paintings of J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837). Though Weaver's style was less overtly Romantic, the era's heightened appreciation for the natural world and rural life undoubtedly contributed to the appeal of his subject matter. His depictions of magnificent animals, products of nature carefully guided by human ingenuity, could be seen as a form of pastoral idyll, albeit one grounded in economic reality.

The broader art scene also included prominent portraitists like Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), who captured the elite of society with dazzling virtuosity, and landscape painters like John Crome (1768-1821) and John Sell Cotman (1782-1842) of the Norwich School, who focused on the specific scenery of their native East Anglia. Weaver's work, therefore, existed within a rich and diverse artistic landscape, catering to a specific but important segment of patronage.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and the Role of Prints

Thomas Weaver consistently exhibited his works at major London venues, which was crucial for maintaining visibility and securing commissions. He showed paintings at the Royal Academy of Arts on numerous occasions between 1801 and 1840. He also exhibited at the British Institution and the Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street. This regular participation in the London art world indicates a professional artist actively engaged with his peers and patrons.

The practice of creating engravings and aquatints after popular paintings was widespread in the 18th and 19th centuries, and Weaver's works were no exception. Prints made his images accessible to a broader audience beyond the original commissioner. They served as advertisements for famous breeds and breeders, and also catered to a growing middle-class market interested in art and agricultural subjects. Artists like William Ward, a renowned engraver and brother of James Ward, often translated paintings into prints. The availability of prints of Weaver's prize animals helped to solidify their fame and, by extension, the artist's reputation.

This system of exhibition and reproduction was vital for artists like Weaver. It allowed them to reach patrons across the country and ensured their work had a lasting impact beyond the lifespan of the original canvas. The detailed nature of his paintings lent itself well to the engraver's art, allowing the specific characteristics of the animals to be faithfully reproduced.

Later Life and Legacy

Thomas Weaver continued to paint and exhibit throughout the first four decades of the 19th century, adapting his style subtly over time but remaining true to his core subject matter. He passed away in 1843, leaving behind a substantial body of work that documents a key period in British agricultural history.

His legacy is multifaceted. Firstly, his paintings are invaluable historical documents. They provide visual evidence of the breeds of livestock that were being developed and celebrated, offering insights into the science and aesthetics of animal breeding in his era. For agricultural historians, his work is a rich resource.

Secondly, from an art historical perspective, Weaver represents a competent and dedicated practitioner within the genre of animal painting. While perhaps not reaching the artistic heights of a Stubbs or the dramatic intensity of a Ward, his work possesses a quiet dignity and an honesty that is appealing. He fulfilled the needs of his patrons with skill and diligence, creating works that were both accurate records and pleasing compositions. His paintings can be found in numerous public and private collections, particularly those with a focus on British art, rural life, or agricultural history, such as the Tate Britain and regional museums.

The appreciation for sporting and animal art has grown in recent decades, and artists like Thomas Weaver are increasingly recognized for their contribution to the British artistic tradition. His paintings offer a window into a world where the land and its produce were central to national identity and prosperity, and where the careful breeding of an ox or a sheep could be a matter of considerable pride and artistic celebration. His work reminds us of the deep historical connections between art, agriculture, and society.

The Market for Weaver's Art: Then and Now

During his lifetime, Thomas Weaver's primary patrons were landowners, gentlemen farmers, and successful breeders. These individuals commissioned portraits of their prize animals or themselves with their livestock, viewing the paintings as status symbols, records of achievement, and sometimes even as tools for promoting their breeding stock. The cost of such commissions would have varied depending on the size and complexity of the work, but they represented a significant investment.

The market for prints after his paintings extended his reach. These engravings were more affordable and allowed a wider public to own images of celebrated animals. This secondary market was an important source of income and recognition for many artists of the period, including those like George Morland, whose rustic scenes were immensely popular in print form.

Today, Thomas Weaver's original paintings appear periodically on the art market, at auctions and through specialist dealers in British art. Prices for his works can vary considerably, influenced by factors such as the size, condition, subject matter (a particularly famous animal or a well-composed group might command higher prices), and provenance. While not typically reaching the astronomical figures of some of his more famous contemporaries like Turner or Constable, good examples of Weaver's work are sought after by collectors of British traditional art, sporting art, and agricultural history. His paintings are appreciated for their historical significance, their charm, and their skilled execution within their specific genre. The enduring appeal of rural life and the British countryside also contributes to the continued interest in his art.

Conclusion

Thomas Weaver carved a distinct niche for himself in the British art world of the late Georgian and early Victorian eras. As a dedicated painter of livestock and rural scenes, he provided an invaluable service to the agricultural community, meticulously documenting their prized animals and, in doing so, chronicling a period of significant agricultural advancement. His work, characterized by its detailed realism and quiet dignity, stands as a testament to the pride and passion invested in British farming.

While operating in a genre that was sometimes considered secondary to the grand historical or mythological subjects favored by the academic establishment, Weaver and his contemporaries in animal and sporting art, such as Philip Reinagle or Abraham Cooper (who was also known for battle scenes), catered to a vital and enthusiastic clientele. Their paintings offer a unique lens through which to view the social, economic, and cultural landscape of their time. Thomas Weaver's legacy endures not only in the galleries and collections that house his work but also in the ongoing appreciation for the rich heritage of British rural life that his art so faithfully represents. His paintings remain a charming and informative record of a bygone era, capturing the essence of agrarian Britain with skill and integrity.