John Carlin (1813-1891) stands as a remarkable figure in the annals of 19th-century American art and deaf history. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Carlin navigated a world largely unaccommodating to the deaf, yet he rose to prominence not only as a gifted painter, particularly of miniatures and genre scenes, but also as a respected poet, writer, and an influential advocate for the deaf community. His life and work offer a compelling narrative of talent, perseverance, and the power of art to transcend barriers.

Early Life and Formative Education

John Carlin was born on June 15, 1813, in Philadelphia, into a family of modest means; his father was a cobbler. He became deaf at a very young age, a circumstance that profoundly shaped his life's trajectory but did not hinder his intellectual or artistic development. Recognizing the importance of specialized education, at the age of twelve, around 1825, he was enrolled in the Mount Airy School, which would later become the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf. This institution, founded by Laurent Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, was a beacon for deaf education in America.

At the Mount Airy School, Carlin received a foundational education that was crucial for his future. He learned to read and write, mastered sign language, and, significantly, received his initial instruction in drawing. This early exposure to artistic practice ignited a passion that would define his professional life. The environment at such schools often fostered a strong sense of community and identity among deaf individuals, and Carlin's experiences there undoubtedly contributed to his later advocacy work. His ability to communicate effectively through written English and sign language, alongside his burgeoning artistic skills, set him on a path of self-reliance and creative expression.

Embarking on an Artistic Career

Upon completing his studies, Carlin was determined to make his way as an artist. The early 19th century in America was a period of growing cultural self-awareness, and portraiture was in high demand. In 1834, at the young age of 21, Carlin demonstrated his entrepreneurial spirit by opening his own studio and gallery in Philadelphia. He initially focused on creating portraits and landscape paintings, seeking to establish his reputation in a competitive field.

His ambition, however, extended beyond the confines of his native city. Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Carlin understood the value of European study to refine his technique and broaden his artistic horizons. The established art academies and the opportunity to study Old Masters firsthand were powerful lures. Philadelphia itself had a burgeoning art scene, with figures like Thomas Sully and Rembrandt Peale being prominent portraitists, and the legacy of Charles Willson Peale and his museum providing a rich artistic environment. Carlin would have been aware of these local masters and the standards they set.

European Sojourn: Refining His Craft

In 1838, John Carlin embarked on a transformative journey to Europe, a common pilgrimage for ambitious American artists seeking to immerse themselves in the continent's rich artistic traditions. His first stop was London, where he dedicated himself to improving his drawing skills. Drawing was considered the bedrock of academic art, essential for accurate representation and compositional strength. London offered access to collections and potentially instruction that would have been invaluable.

Following his time in London, Carlin moved to Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. There, he had the distinct privilege of studying under Paul Delaroche (1797-1856), one of the most famous and respected academic painters of his era. Delaroche was renowned for his meticulously detailed historical scenes, such as "The Execution of Lady Jane Grey," and his insightful portraits. Studying in Delaroche's atelier would have exposed Carlin to rigorous academic training, emphasizing precision, careful modeling of form, and polished finish. This experience undoubtedly honed his technical abilities, particularly in capturing likenesses and rendering detail, skills that would serve him well in his later specialization in miniature painting. Other artists who benefited from Delaroche's tutelage included Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean-François Millet, highlighting the caliber of instruction Carlin received.

During his time abroad, Carlin was not solely focused on painting. He continued to develop his literary talents, reportedly working on sketches for illustrations of John Milton's "Paradise Lost" and John Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress," and also engaging in poetry and translation. This multifaceted intellectual engagement was characteristic of Carlin throughout his life.

Return to America and Mastery of Miniature Painting

John Carlin returned to the United States in 1841, his skills significantly enhanced by his European studies. He chose to settle in New York City, which was rapidly becoming the nation's leading artistic and commercial center. It was here that Carlin truly distinguished himself as a master of miniature portraiture. Miniature painting, typically executed on ivory or vellum, required extraordinary precision and a delicate touch. Before the widespread adoption of photography, miniatures served as intimate keepsakes, cherished mementos of loved ones.

Carlin's meticulous technique, likely refined under Delaroche, was perfectly suited to this demanding art form. He gained a considerable reputation for his lifelike and finely wrought miniatures, attracting a distinguished clientele. He worked alongside other miniaturists active in New York and Philadelphia, such as George Freeman and George Lethbridge Saunders, who also catered to the demand for these small, precious portraits. The demand for miniatures was high, and Carlin's ability to capture not just a likeness but also a sense of the sitter's personality made his work highly sought after. His success in this field provided him with a stable income and a platform for his artistic endeavors.

Expanding Horizons: Portraits and Genre Scenes

While renowned for his miniatures, John Carlin's artistic output was not limited to this specialty. He also painted larger-scale portraits and, significantly, genre scenes. His portraits captured a diverse range of individuals, and his skill in this area was widely acknowledged. One of his most notable portraits is that of Laurent Clerc, the pioneering deaf educator who had co-founded the American School for the Deaf and the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf, where Carlin himself had studied. This portrait, commissioned by the Kentucky School for the Deaf, remains a testament to Carlin's respect for his mentor and his connection to the deaf community. It is said to still hang in the school's chapel.

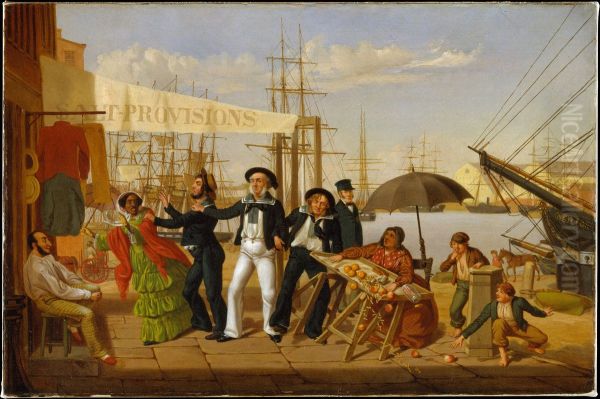

Carlin's genre paintings offer a fascinating glimpse into mid-19th-century American life, often imbued with a gentle humor and keen observation. Perhaps his most famous genre scene is "After a Long Cruise" (1857), now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This lively painting depicts sailors returning to port in New York, joyfully greeted by their families. The work is characterized by its vibrant color, detailed rendering of figures and setting, and a narrative quality that engages the viewer. It showcases Carlin's ability to compose complex scenes and capture a sense of everyday life, a departure from the more formal demands of portraiture. This painting aligns with a broader trend in American art, exemplified by artists like William Sidney Mount and George Caleb Bingham, who found inspiration in the activities and stories of ordinary Americans.

Artistic Style: Precision, Realism, and Narrative

John Carlin's artistic style is characterized by its meticulous attention to detail, a hallmark of his miniature work that carried over into his larger paintings. He adhered to a broadly realistic approach, aiming for accurate representation and a clear depiction of his subjects. His training under Paul Delaroche would have reinforced a commitment to polished finishes and careful draftsmanship, typical of the academic tradition.

In his portraits, Carlin sought to capture not just the physical likeness but also the character and personality of his sitters. This psychological insight, combined with his technical skill, made his portraits compelling. In his genre scenes, such as "After a Long Cruise," there is a strong narrative element. He constructs scenes that tell a story, often with an element of warmth or humor, inviting viewers to engage with the depicted events and characters. His use of color was often bright and appealing, contributing to the accessibility of his work. While not an innovator in the sense of breaking from established artistic conventions, Carlin was a highly skilled practitioner who adapted academic principles to American subjects and sensibilities. His work can be situated within the broader currents of 19th-century American realism, alongside contemporaries who sought to depict the burgeoning nation and its people.

A Champion for the Deaf Community

Beyond his artistic achievements, John Carlin was a tireless advocate for the rights and education of deaf individuals. Having experienced firsthand the challenges and opportunities available to the deaf, he dedicated much of his energy to improving their social standing and access to education. He was a prolific writer and poet, using his literary talents to give voice to the experiences and aspirations of the deaf community.

His poem, "A Mute’s Lament," poignantly expresses the frustrations and hopes of a deaf person in a hearing world. He also wrote influential articles, such as "The National College for the Deaf," advocating for higher education for deaf students. Carlin played a significant role in the movement that led to the establishment of the National Deaf-Mute College in Washington, D.C., in 1864, which is now Gallaudet University. He was honored with the first Master of Arts degree conferred by the institution, a testament to his intellectual contributions and his advocacy. He was a respected public speaker, using sign language to communicate effectively with deaf audiences and to champion their cause before the wider public. His efforts helped to foster a sense of pride and community among deaf Americans and contributed to tangible improvements in their educational opportunities.

Connections and Contemporaries

Throughout his career, John Carlin moved within notable artistic and social circles. His tutelage under Paul Delaroche in Paris connected him to a major stream of European academic art. In America, his work as a portraitist brought him into contact with prominent individuals. The provided information mentions friendships with figures such as Jefferson Davis (before he became President of the Confederacy), Jane Pierce (wife of President Franklin Pierce), and Senator William H. Seward. These connections underscore his standing in society.

In the art world, he would have been aware of, and likely interacted with, many leading American artists of his time. The field of portraiture included figures like George Peter Alexander Healy, Daniel Huntington, and Charles Loring Elliott. The Hudson River School, with landscape painters such as Asher B. Durand (who also began as an engraver and portraitist), Frederic Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt, was defining American landscape painting. Genre painters like Eastman Johnson were also gaining prominence. While Carlin's primary focus differed from these landscape and genre specialists in some respects, he was part of this vibrant, evolving American art scene. His teachers, John Neagle and John Reubens Smith, were also established figures in the Philadelphia art community.

Anecdotes, Perceptions, and Challenges

John Carlin's deafness was an intrinsic part of his identity and, undoubtedly, shaped perceptions of him and his work. In an era with less understanding of deafness, his achievements were all the more remarkable. He overcame significant communication barriers to study in Europe and build a successful career.

The suggestion that some of his work, particularly his genre scenes with their humorous elements, might have been considered "lowbrow" by certain segments of society is plausible. The 19th century saw ongoing debates about "high art" versus "popular art." Academic art, often focused on historical, mythological, or religious subjects, was generally held in higher esteem than genre scenes depicting everyday life, especially those with a humorous or anecdotal quality. However, genre painting was gaining popularity in America, reflecting a democratic spirit and an interest in national identity. Carlin's engagement with such themes, as in "After a Long Cruise," suggests an artist attuned to these evolving tastes, even if they diverged from the more classical or "elevated" subjects favored by strict academic tradition. His success indicates that his work found an appreciative audience.

Literary Contributions and Children's Literature

Carlin's talents were not confined to the visual arts. He was a recognized poet and writer. His poem "A Mute's Lament" is a significant piece, articulating the inner world of a deaf individual with eloquence and emotion. He also contributed articles on deaf education and advocacy, demonstrating his intellectual engagement with the issues facing his community.

Interestingly, Carlin also ventured into children's literature. He authored and illustrated a book titled "The Scratchiest Family" (sometimes cited as "The Itchiest Family"). This work, featuring his own illustrations, showcases another dimension of his creativity and his ability to connect with a younger audience. Creating children's books was not uncommon for artists, but for Carlin, it represented another avenue for expression and perhaps a way to subtly promote understanding and empathy. His diverse literary output complements his artistic achievements, painting a picture of a man with wide-ranging intellectual and creative interests.

Legacy and Lasting Influence

John Carlin passed away on April 23, 1891, in New York City, leaving behind a significant legacy. As an artist, he is remembered for his exquisite miniatures, his insightful portraits, and his engaging genre scenes. Works like "After a Long Cruise" and his portrait of Laurent Clerc hold important places in American art history and the history of the deaf community, respectively. His technical skill, honed through rigorous training, is evident in the quality and refinement of his paintings.

Perhaps even more enduring is his impact as an advocate for the deaf. His passionate efforts to promote deaf education, his role in the founding of what became Gallaudet University, and his articulate writings and speeches helped to empower the deaf community and advance their cause. He demonstrated through his own life that deafness was not a barrier to profound intellectual and artistic achievement. He served as an inspiring role model for generations of deaf individuals.

In art historical evaluations, Carlin is recognized for his contributions to American portraiture and genre painting in the mid-19th century. He is a notable example of an American artist who successfully combined European training with American subjects and sensibilities. His unique position as a prominent deaf artist in a hearing world adds another layer to his significance, making his story one of resilience, talent, and advocacy. He is distinct from the contemporary artist John Currin (b. 1962), whose style and thematic concerns are vastly different, and it's important to maintain this distinction. John Carlin's contributions ensure his place as a respected and multifaceted figure in American cultural history.

Conclusion

John Carlin's life was a testament to the power of the human spirit to overcome adversity and achieve excellence. As a deaf artist in 19th-century America, he carved out a successful career, producing works of lasting beauty and historical importance. His mastery of miniature painting, his sensitive portraits, and his lively genre scenes reflect a keen eye and a skilled hand. Simultaneously, his unwavering dedication to the cause of deaf education and rights established him as a pivotal figure in the history of the American deaf community. John Carlin's legacy is thus twofold: that of a gifted artist who captured the likenesses and life of his era, and that of a pioneering advocate who helped to open doors and create opportunities for others. His story continues to inspire, reminding us of the profound impact one individual can have on both the cultural landscape and the social fabric of their time.