Harry Humphrey Moore (1844-1926) stands as a notable figure in American art history, particularly distinguished for his contributions to Orientalist painting and his pioneering depictions of Japanese culture. His life and career were marked by a unique personal journey, overcoming profound hearing loss to forge an international artistic path that spanned continents and absorbed diverse cultural influences. Moore's legacy is one of meticulous observation, vibrant portrayal, and a deep engagement with the peoples and places he encountered, leaving behind a body of work that offers a fascinating window into late 19th and early 20th-century artistic trends and cross-cultural encounters.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in New York City in 1844, Harry Humphrey Moore hailed from a prosperous family. His father was George Humphrey Moore, a successful shipbuilder, and he was also a descendant of the esteemed English painter Ozias Humphrey (1742-1810), suggesting an early familial connection to the arts. A significant challenge marked Moore's early childhood: at the tender age of three, he lost his hearing. This profound deafness necessitated specialized education, and he diligently learned lip-reading and sign language, which became his primary means of communication throughout his life.

Despite this obstacle, Moore's artistic inclinations emerged early. His initial artistic instruction came from Samuel Waugh and Louis Bail in New York. Seeking further development, he later moved to San Francisco, where he received training at the Mark Hopkins Institute (later the San Francisco Art Institute). These formative experiences laid the groundwork for a career that would see him travel extensively and absorb a wide range of artistic influences. His determination to pursue art, despite his deafness, speaks volumes about his passion and resilience.

European Sojourn and Academic Foundations

The mid-1860s marked a pivotal period for Moore as he embarked on a European tour, a common practice for aspiring American artists of the era seeking to immerse themselves in the continent's rich artistic heritage. Between 1864 and 1865, his travels took him to key artistic centers, including Munich, Paris, and Rome. It was in Paris that he encountered one of the most significant influences on his artistic development: Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Moore enrolled in Gérôme's atelier, a highly sought-after place of study. Gérôme was a towering figure in French Academic art, renowned for his meticulously detailed historical and Orientalist scenes. Under Gérôme's tutelage, Moore absorbed the principles of precise draughtsmanship, polished finish, and a commitment to verisimilitude that characterized the academic tradition. Gérôme's own fascination with North African and Middle Eastern subjects likely played a role in kindling Moore's later interest in Orientalist themes. During his time in Paris, Moore would have been in an environment bustling with artistic talent; for instance, Thomas Eakins, another prominent American painter, also studied with Gérôme around this period.

Following his studies in Paris, Moore continued his artistic education in Rome. The Italian capital, with its classical ruins and Renaissance masterpieces, offered another layer of artistic enrichment. Here, he reportedly interacted with Spanish painters, including Mariano Ricote Martín and Juan Martín Rodríguez. This exposure to Spanish art, particularly the vibrant colors and lively genre scenes often associated with it, may have further broadened his stylistic palette. The great Spanish master Mariano Fortuny y Marsal was also active in Rome and Paris during these years, and his dazzling Orientalist works and genre scenes were highly influential, potentially impacting Moore's developing vision.

Pioneering in Morocco: The Allure of the Exotic

In the 1870s, Harry Humphrey Moore ventured into a region then considered highly exotic and relatively unexplored by American artists: Morocco. He was among the first wave of American painters to work extensively in this North African country, drawn by its vibrant culture, distinct architecture, and the "picturesque" quality of its daily life. This period marked a significant phase in his development as an Orientalist painter.

Moore dedicated himself to capturing the essence of Morocco. His canvases from this time often feature bustling marketplaces, intricate architectural details of mosques and traditional dwellings, and portraits of local inhabitants in their traditional attire. His works from Morocco are characterized by a keen eye for detail, likely honed under Gérôme, combined with a sensitivity to the unique atmosphere of the region. He employed a delicate brushstroke and a palette that could convey both the bright North African light and the rich textures of textiles and decorative arts.

His Moroccan paintings contributed to the growing fascination with "the Orient" in Western art and popular culture. Artists like John Singer Sargent, though perhaps more famously associated with Venice and society portraiture, also traveled to North Africa and painted Orientalist subjects, reflecting a broader artistic trend. Moore's early immersion in this genre positioned him as a significant American contributor to Orientalist art, capturing scenes that were both documentary in their detail and romantic in their appeal to Western audiences.

A Groundbreaking Journey to Japan: Immersing in a New Culture

Perhaps the most distinctive and pioneering phase of Harry Humphrey Moore's career was his journey to Japan from 1880 to 1881. At this time, Japan had only relatively recently opened its borders to the West after centuries of isolation, and few Western artists had ventured there to live and work. Moore was among the vanguard of American artists to explore Japanese culture firsthand, an experience that profoundly impacted his art.

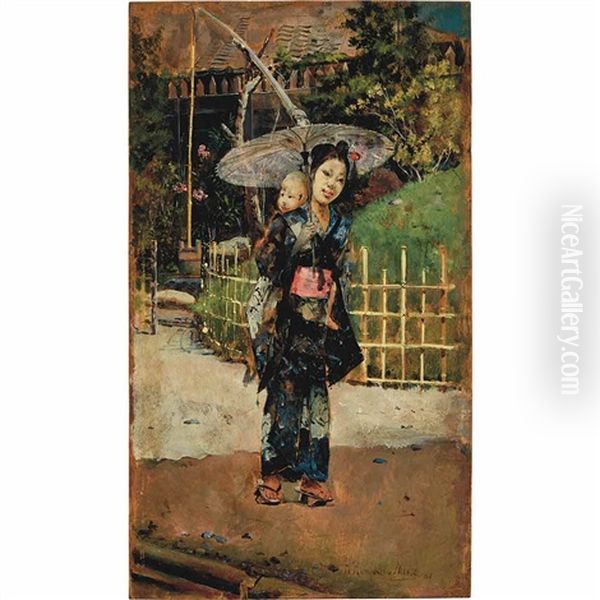

He spent considerable time in major cities like Tokyo, Yokohama, and Kyoto, immersing himself in the local environment. Unlike artists who relied on photographs or Japanese prints seen in the West, Moore directly observed the daily lives of Japanese people. He was particularly drawn to depicting children and family life, capturing intimate moments with sensitivity and charm. His Japanese works often feature figures in traditional kimonos, engaged in everyday activities, set against backdrops of Japanese homes or gardens.

Moore produced a significant body of work during and after his Japanese sojourn, reportedly creating around sixty paintings on wood panels. These pieces are celebrated for their vibrant colors, lively compositions, and the palpable sense of empathy Moore felt for his subjects. His depictions went beyond mere exoticism, reflecting a genuine effort to understand and portray Japanese customs and social fabric. This deep engagement distinguished his work from more superficial Japonisme that was becoming fashionable in the West, which often focused on stylistic borrowings rather than cultural immersion.

His experiences in Japan were groundbreaking. Other American artists, such as John La Farge, Robert Frederick Blum, and Theodore Wores, also traveled to Japan around this period or shortly thereafter, contributing to an American understanding and artistic interpretation of Japanese culture. La Farge, for instance, was known for his stained glass and murals, and his Japanese-inspired works were highly influential. Blum became particularly noted for his depictions of Japanese life, and Wores also dedicated a significant portion of his career to Japanese subjects. Moore, however, was among the very first to provide such an extensive visual record from an American perspective.

Artistic Style, Thematic Focus, and Representative Works

Harry Humphrey Moore's artistic style evolved throughout his career, shaped by his academic training and his extensive travels. A consistent thread, however, was his commitment to detailed representation and his fascination with cultural subjects. His work can be broadly categorized within the Orientalist and Japoniste movements, but also includes significant portraiture.

His training under Gérôme instilled in him a respect for meticulous detail and a polished finish, evident in the careful rendering of textures, costumes, and architectural elements in his paintings. When depicting Moroccan scenes, his style aligned with the broader Orientalist tradition, emphasizing the "exotic" and often romanticized aspects of North African life. He used a rich color palette to convey the vibrancy of the markets and the intensity of the light.

Moore's Japanese works, while still detailed, often possess a particular charm and intimacy. His focus on children and domestic scenes allowed for a gentler, more observational approach. He skillfully captured the patterns of kimonos, the expressions of his subjects, and the specificities of Japanese interiors and gardens. These works are characterized by bright, clear colors and a sense of immediacy.

One of his most well-known works is Japanese Girl Promenading, created in 1881. This painting exemplifies his Japanese period, depicting a young woman in traditional attire, possibly carrying a child on her back, in a setting that evokes everyday Japanese life. The artwork is noted for its vibrant colors, the careful depiction of the kimono, and the gentle, observant portrayal of the subject. It showcases his ability to combine ethnographic detail with artistic sensitivity.

Another representative work mentioned is Girl Holding a King Charles Spaniel. While the specific context of this piece isn't as detailed in the provided information, it suggests his engagement with portraiture, a genre he continued to pursue upon his return to the United States. Such a subject, common in Western portraiture, would contrast with his Orientalist and Japanese themes, highlighting his versatility.

Upon returning to the United States, Moore settled in New York City. He continued to paint, focusing on portraits, often of children, aristocrats, and prominent social figures. His Japanese subjects remained particularly popular, capitalizing on the Western fascination with Japanese culture that was then at its height, a phenomenon often termed Japonisme, which influenced artists like James McNeill Whistler and Mary Cassatt in their compositions and subject matter.

Interactions with Contemporaries and Influence

Throughout his career, Harry Humphrey Moore moved within significant artistic circles, both in America and abroad. His decision to study under Jean-Léon Gérôme in Paris placed him at the heart of the academic art world. Gérôme's atelier was a hub for international students, and Moore's contemporaries there included figures like Thomas Eakins, who would go on to become one of America's most important realist painters. The shared experience of rigorous academic training under such a dominant figure would have fostered a unique camaraderie and exchange of ideas.

His time in Rome and his interactions with Spanish painters like Mariano Ricote Martín and Juan Martín Rodríguez, and his likely awareness of the work of Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, connected him to the vibrant Spanish art scene. Fortuny, in particular, was a sensation, and his influence on Orientalist painting and genre scenes was widespread. Moore's exposure to these artists would have enriched his understanding of color, light, and composition.

Moore's pioneering work in Japan did not go unnoticed. His depictions of Japanese life were among the earliest by an American artist working extensively in the country. This naturally drew the attention of other artists interested in Japan. Figures like Robert Frederick Blum, Theodore Wores, and John La Farge, who also made significant contributions to the Western artistic interpretation of Japan, were part of a wave of artists exploring this newly accessible culture. While the exact nature of his direct interactions with all of them isn't fully detailed, his work would have been known within these circles. For instance, La Farge was an older, established artist whose travel to Japan with Henry Adams was a significant cultural event. Blum and Wores were closer contemporaries who also dedicated substantial efforts to depicting Japan.

The broader context of American art at the time included figures like Winslow Homer, known for his powerful depictions of American life and the sea, and landscape painters of the Hudson River School tradition like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, who captured the grandeur of the American continent. While Moore's focus was distinctly international and ethnographic, he operated within an American art world that was increasingly looking both inward at its own identity and outward to global cultures. His choice to depict foreign lands and peoples set him apart from many of his American contemporaries who focused on domestic scenes or landscapes, aligning him more with the cosmopolitan and internationally-minded artists of his generation.

His early teachers, Samuel Waugh and Louis Bail, provided his foundational training, while Adolphe Yvon, another prominent French academic painter whom he reportedly studied under, would have further reinforced the principles of historical and large-scale composition. These connections illustrate a career built on diverse educational experiences and engagement with leading artistic figures of his time.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Harry Humphrey Moore's art received considerable acclaim during his lifetime, particularly for its exotic themes, bright and appealing color palette, and the perceived authenticity of his detailed depictions. His formal training in Paris under Gérôme lent his work an academic credibility, while his adventurous travels provided him with unique and captivating subject matter.

His contributions to American Orientalism are significant, especially his early work in Morocco. He was among the first American artists to immerse himself in the region and bring back vivid portrayals of its culture. These works catered to a Western audience eager for glimpses into what they considered exotic and distant lands, and Moore provided these with a skilled hand and an observant eye.

However, it is arguably his work in Japan that constitutes his most unique and lasting legacy. As one of the very first American artists to live and paint extensively in Japan, he played a crucial role in introducing Japanese life and culture to American audiences through fine art. His paintings from this period are valued not only for their artistic merit—their vibrant colors and lively scenes—but also as important historical documents. They reflect a deep observation and an empathetic understanding of Japanese culture, going beyond superficial exoticism.

The anecdote about his refusal to sell his collection of Japanese paintings to the Parisian art dealers Goupy & Cie, choosing instead to keep them as cherished memories of his time there, speaks to the personal significance of this experience. It suggests that his engagement with Japan was more than just a source of novel subject matter; it was a deeply formative personal and artistic journey. This decision, while perhaps limiting the immediate commercial dissemination of these specific works, underscores his profound connection to his Japanese experiences.

Historically, Moore is recognized as a pioneer. His willingness to travel to and immerse himself in distant cultures, especially considering the communication challenges posed by his deafness, is remarkable. His work provided a bridge between cultures, offering Western viewers a nuanced and detailed look at societies that were, at the time, largely unknown or misunderstood. While the lens of Orientalism and Japonisme is now understood within a complex post-colonial critique, Moore's dedication to firsthand observation and his evident respect for the cultures he depicted lend his work a particular integrity.

Conclusion: A Life Forged in Art and Exploration

Harry Humphrey Moore's life was a testament to the power of art to transcend personal challenges and bridge cultural divides. From his early artistic training in New York and San Francisco to his immersive experiences in the academic circles of Paris, the vibrant landscapes of Morocco, and the rich cultural tapestry of Japan, Moore forged a unique artistic path. His deafness, rather than hindering him, perhaps sharpened his visual acuity and deepened his observational skills, allowing him to capture the nuances of the worlds he explored with remarkable detail and sensitivity.

As an artist, he was a skilled practitioner of academic realism, yet his true distinction lies in his role as a cultural interpreter. His paintings of Morocco and, most notably, Japan, stand as important contributions to American Orientalism and the early artistic engagement with Japanese culture. Works like Japanese Girl Promenading continue to be appreciated for their aesthetic qualities and their historical significance, offering a glimpse into a world captured by an artist who dared to venture far beyond the familiar. Harry Humphrey Moore's legacy is that of a dedicated, resilient, and adventurous painter who expanded the horizons of American art through his profound engagement with diverse global cultures.