John Constable (1776-1837) stands as one of the most influential figures in British art history, a painter whose dedication to the landscapes of his native Suffolk revolutionized the genre and paved the way for future artistic movements. Living and working during the height of the Romantic era, Constable rejected the idealized, classical landscapes favored by many contemporaries, choosing instead to capture the authentic beauty, changing light, and atmospheric conditions of the English countryside he knew intimately. His work, characterized by its naturalism, emotional depth, and innovative technique, continues to resonate with audiences today.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Constable was born on June 11, 1776, in East Bergholt, a village nestled in the picturesque Stour Valley of Suffolk, England. He was the second son of Golding and Ann Constable. His father was a prosperous corn merchant and miller, owning Flatford Mill and later Dedham Mill, as well as managing a mill in East Bergholt itself. The family's wealth also stemmed from coal trading, providing a comfortable and stable upbringing for young John. His mother, Ann, managed the domestic side of their enterprise, overseeing aspects like the household brewery and dairy.

The Suffolk landscape, with its gentle rivers, rolling fields, water meadows, and dramatic skies, became Constable's first and most enduring love. His childhood spent exploring the area around his father's mills deeply imprinted upon him the sights, sounds, and textures of rural England. This environment, later affectionately termed "Constable Country," would become the primary subject matter for his entire artistic career.

Initially, Golding Constable hoped his son would enter the clergy or, failing that, join the family milling business. John's elder brother, also named Golding, had an intellectual disability, making him unsuitable to take over. For a time, John did work alongside his father, learning the intricacies of the milling trade. However, his passion lay elsewhere. From a young age, he demonstrated a keen interest in drawing and painting, often sketching outdoors. He formed a friendship with John Dunthorne, a local plumber, glazier, and amateur painter, who shared his enthusiasm for observing and sketching nature directly.

Despite his father's initial reservations, Constable's artistic inclinations eventually won out. Recognizing his son's talent and determination, Golding granted him a small allowance and permission to pursue art seriously. In 1799, Constable traveled to London and enrolled as a probationer at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. There, he received formal training, studying anatomy, drawing from plaster casts and life models, and dissecting human bodies to understand structure. He also immersed himself in the works of Old Masters, particularly admiring the landscapes of Claude Lorrain, the naturalism of Dutch painters like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema, and the rich textures and compositions of Peter Paul Rubens and Thomas Gainsborough, whose own Suffolk roots likely resonated with Constable.

The Development of a Unique Vision

Constable's time at the Royal Academy provided essential technical grounding, but his artistic heart remained firmly rooted in the Suffolk countryside. He famously declared in 1802, "For the last two years I have been running after pictures, and seeking the truth at second hand... I shall return to Bergholt, where I shall endeavour to get a pure and unaffected manner of representing the scenes that may employ me... There is room enough for a natural painture." This marked a turning point, a conscious decision to prioritize direct observation and personal experience over academic convention and the imitation of established styles.

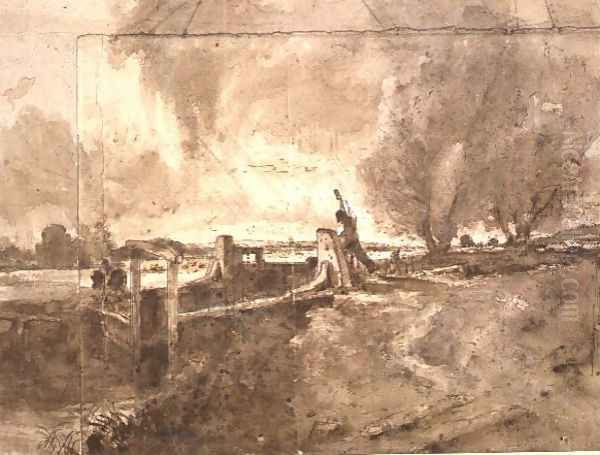

He became a pioneer of plein air (outdoor) sketching, taking small, portable easels and oil paints directly into the fields and along the riverbanks. These oil sketches, often completed rapidly to capture fleeting effects of light and weather, were crucial to his process. They were not typically intended as finished works for exhibition but served as vital reference material, imbued with an immediacy and freshness that he sought to translate into his larger studio paintings. His cloud studies, in particular, demonstrate an almost scientific approach to observation, meticulously noting the date, time, and weather conditions on the back of the sketches.

Constable believed that landscape painting should be based on observable facts, on the specific character of a place under particular conditions. He rejected the picturesque conventions popular at the time, which often involved rearranging natural elements to create an idealized, aesthetically pleasing composition. Instead, he focused on the "chiaroscuro of nature"—the interplay of light and shadow—and the transient effects of weather, seeking to capture the sparkle of dew on grass, the movement of clouds across the sky, and the reflections of light on water. His dedication was to truthfulness, aiming to paint familiar scenes with deep feeling and accuracy.

His primary focus remained the Stour Valley, the area encompassing Flatford, Dedham, and East Bergholt. He painted the locks, mills, towpaths, and farmhouses he had known since childhood, viewing these ordinary scenes with profound affection and finding in them endless artistic inspiration. Works like Dedham Vale (1802) show his early commitment to this landscape, a theme he would return to throughout his career with increasing sophistication.

Masterworks and the "Six-Footers"

While Constable produced numerous smaller paintings and sketches, he is perhaps best known for his series of large-scale canvases, often referred to as the "six-footers" due to their approximate width. These ambitious works, intended for exhibition at the Royal Academy, aimed to elevate landscape painting to the status historically accorded to grand history painting. They represent the culmination of his outdoor studies and studio work, synthesizing detailed observation with powerful composition and emotional resonance.

Among the most celebrated is The Hay Wain (1821). Depicting a hay cart (or wain) crossing the River Stour near Willy Lott's Cottage (a house still standing today), the painting is a quintessential image of rural England. Its detailed rendering of foliage, water, and sky, combined with a sense of peaceful, working life, captured the public imagination, particularly when exhibited in France. It remains one of the most iconic works in British art.

The White Horse (1819) was the first of the six-footers and earned Constable election as an Associate of the Royal Academy. It shows a barge horse being ferried across the Stour, notable for its vigorous handling of paint and dramatic sky. Stratford Mill (1820), sometimes known as The Young Waltonians, depicts another scene on the Stour, featuring anglers near the mill, showcasing his mastery of light on water and complex reflections.

The Leaping Horse (1825) is perhaps the most dynamic of the series, capturing the moment a barge horse jumps over a barrier on the towpath. The energy of the horse, the turbulent sky, and the textured application of paint convey a sense of raw natural power and movement. The Lock (1824) returns to a calmer scene, depicting a barge passing through a lock on the Stour, bathed in shimmering light. This work proved commercially successful for Constable.

Later in his career, Constable expanded his subject matter beyond Suffolk, notably painting several views of Salisbury Cathedral, often from the grounds of his friend Archdeacon John Fisher's house. Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds (c. 1823 and later versions) is a majestic work, capturing the soaring Gothic architecture under dramatic, cloud-filled skies, reflecting both the sublime power of nature and perhaps a spiritual dimension. Wivenhoe Park, Essex (1816), an earlier commission, demonstrates his skill in rendering a specific estate with meticulous detail while still imbuing it with atmospheric life.

A key aspect of Constable's process for the six-footers was the creation of full-size oil sketches. These were not mere preliminary drawings but fully worked-out compositions in oil, often executed with remarkable freedom and energy. Comparing these sketches to the final exhibition pieces reveals his working method: the sketches often possess a raw vigour and spontaneity, while the finished paintings show greater refinement and detail, though sometimes at the expense of the initial sketch's freshness.

Technique and Artistic Style

Constable's technique was as innovative as his vision. He developed a highly personal style characterized by several key features. His brushwork was often bold and broken, using small dabs and strokes of colour applied side-by-side or layered to create texture and vibrancy. He frequently used a palette knife to apply thick impasto, particularly for highlights on water or foliage, giving his surfaces a tangible, almost sculptural quality.

He was a master of capturing light. His famous use of flickering touches of white paint, often referred to as "Constable's snow," was employed not to depict actual snow but to represent the sparkle of sunlight on leaves and water, adding vibrancy and a sense of movement to his scenes. This technique, while criticized by some contemporaries as unfinished or messy, was crucial to conveying the transient effects of light he observed so closely.

His colour palette was generally naturalistic, based on the greens, browns, and blues of the English landscape. However, he understood the importance of complementary colours, often using touches of red (visible in details like harnesses or poppies) to enhance the vibrancy of the dominant greens. His skies were never mere backdrops but active, expressive elements of the composition, reflecting his deep study of meteorology and cloud formations. He believed the sky was the "key note, the standard of scale, and the chief organ of sentiment" in a landscape painting.

Constable often employed a technique similar to wet-on-wet painting, particularly in his sketches, allowing colours to blend slightly on the canvas, contributing to the atmospheric unity of the work. His commitment to naturalism meant rendering details accurately – the specific types of trees, the structure of locks and mills, the textures of bark and stone – yet always within the context of the overall atmospheric effect. His paintings feel lived-in, capturing not just the appearance of the landscape but the feeling of being within it.

Personal Life and Professional Challenges

Constable's personal life was marked by deep affection but also significant challenges. In 1809, he declared his love for Maria Bicknell, whose grandfather was the rector of East Bergholt. Their courtship was long and fraught with difficulty. Maria's family, particularly her grandfather Dr. Durand Rhudde, strongly disapproved of the match, considering the Constable family socially inferior and viewing John's profession as financially unstable. They threatened Maria with disinheritance if she married him.

Despite this opposition, John and Maria remained devoted to each other, maintaining a clandestine correspondence for years. They finally married in October 1816, after the death of Constable's father secured him a degree of financial independence (he inherited a one-fifth share in the family business, now managed by his brother Abram). The marriage, officiated by John's close friend, the Reverend John Fisher (later Archdeacon of Berkshire), was a source of great happiness for Constable.

Maria became his muse and steadfast supporter, and they had seven children together. However, their happiness was overshadowed by Maria's declining health. She suffered from tuberculosis, and Constable spent considerable time and resources seeking cures and moving the family to healthier locations like Hampstead Heath, known for its fresh air. Tragically, Maria died in November 1828 at the age of 41. Her death devastated Constable, plunging him into deep grief from which he never fully recovered. He wore mourning clothes for the rest of his life and took on the sole responsibility of raising their young children.

Professionally, Constable faced ongoing struggles for recognition within the British art establishment. While respected by some fellow artists, his work often met with criticism for its perceived lack of finish and departure from classical ideals. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1819, but full membership as a Royal Academician (RA) eluded him until 1829, relatively late in his career. This delay was a source of considerable frustration for him. He felt undervalued in his own country, particularly in comparison to the more dramatic and commercially successful landscapes of his contemporary, J.M.W. Turner.

Financial worries were also a persistent issue. Although he inherited money, supporting a large family and maintaining studios in London and Hampstead strained his resources. In the late 1820s and early 1830s, he collaborated with the engraver David Lucas on a series of mezzotints based on his paintings, titled Various Subjects of Landscape, Characteristic of English Scenery. While intended to promote his work and generate income, the project proved costly and commercially disappointing, adding to his financial burdens. Despite these challenges, he remained dedicated to his artistic principles, continuing to paint and lecture on landscape painting at the Royal Institution and the RA. He never travelled outside of England, finding all the inspiration he needed in his native land.

Reception and Influence During His Lifetime

Constable's reception during his lifetime was complex and often contradictory. In England, while he exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy, critical opinion was divided. Some admired his naturalism and originality, but many found his broken brushwork and emphasis on ordinary scenery unsettling or crude compared to the polished, idealized landscapes then in vogue. Critics sometimes complained his paintings looked "unfinished" or that his use of white highlights resembled "snow." He sold relatively few large paintings in England during his lifetime.

The situation in France was markedly different. In 1824, the Parisian art dealer John Arrowsmith exhibited several of Constable's works, including The Hay Wain, at the Paris Salon. The paintings caused a sensation. French artists and critics were struck by their freshness, naturalism, and bold technique. The Hay Wain was awarded a gold medal by King Charles X. Eugène Delacroix, the leading figure of French Romantic painting, was reportedly so impressed by Constable's handling of light and colour that he repainted parts of his own masterpiece, The Massacre at Chios, after seeing Constable's work.

This French acclaim, while gratifying, did little to immediately boost Constable's standing in England. However, it planted the seeds for his future influence abroad. His success in Paris highlighted a growing divergence between British and French artistic tastes, with the French proving more receptive to the innovations inherent in Constable's approach to landscape. His emphasis on direct observation, capturing specific atmospheric effects, and using broken colour resonated with French artists who were themselves beginning to challenge Neoclassical conventions.

Enduring Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

John Constable died suddenly on the night of March 31, 1837, in Hampstead. While his reputation in England was still developing at the time of his death, his influence grew steadily in the following decades, particularly on the continent.

His most significant impact was on the development of French landscape painting. The artists of the Barbizon School, active from the 1830s onwards, shared Constable's commitment to painting directly from nature and depicting rural life realistically. Figures like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny admired Constable's naturalism and atmospheric effects. They sought to capture the specific character of the French countryside, particularly the Forest of Fontainebleau, echoing Constable's devotion to his native Suffolk.

Constable's influence extended further to the Impressionists, who emerged in the 1860s and 1870s. His emphasis on capturing fleeting moments of light and weather, his use of broken brushwork and vibrant colour, and his practice of plein air sketching were all precursors to Impressionist techniques and concerns. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley studied Constable's work, recognizing him as a pioneer in the objective study of nature and the representation of light. Gustave Courbet, the leading figure of French Realism, also acknowledged Constable's importance in grounding art in tangible reality.

In Britain, Constable's legacy took longer to fully mature but eventually secured his position as a national icon. His dedication to the English landscape resonated with Victorian sensibilities, and his works became synonymous with an idealized vision of rural England. Later generations of British artists looked to him as a foundational figure who asserted the importance of native scenery and direct observation.

Constable's Place in Art History

John Constable occupies a pivotal position in the history of Western art. He fundamentally changed the way landscape was perceived and painted. By rejecting idealized formulas and focusing on the specific, observable realities of his environment, he infused landscape painting with a new level of naturalism and emotional sincerity. His work embodies key tenets of Romanticism – the emphasis on individual feeling, the power and beauty of nature, and a connection to one's homeland – yet his methods anticipated the scientific objectivity that would characterize Realism and Impressionism.

He demonstrated that ordinary, familiar scenes could be subjects for great art, elevating the status of landscape painting. His innovative techniques, particularly his handling of light and his expressive brushwork, opened up new possibilities for representing the natural world. While J.M.W. Turner explored the sublime and dramatic potential of nature, Constable focused on its intimate, tangible beauty, capturing the "dewy freshness" of the English countryside.

Today, John Constable is celebrated as one of Britain's greatest artists. His paintings, particularly the iconic Hay Wain, are beloved national treasures. His deep love for the Suffolk landscape, combined with his revolutionary artistic vision and technique, ensures his enduring importance as a master painter who taught the world to see the beauty in the everyday, natural world around them. His influence continues to be felt, reminding us of the power of close observation and the profound connection between art and nature.