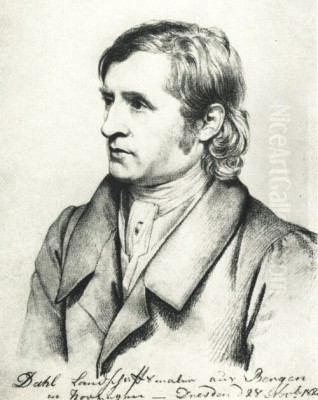

Johan Christian Claussen Dahl, often known simply as J.C. Dahl, stands as a monumental figure in the history of Norwegian art. Born on February 24, 1788, in Bergen, Norway, and passing away on October 14, 1857, in Dresden, Germany (then Kingdom of Saxony), Dahl is widely revered as the "father of Norwegian landscape painting." He was not only the first Norwegian painter to achieve significant international renown but also a foundational pillar of the artistic period known as the Norwegian National Romanticism, often referred to as the "Golden Age" of Norwegian painting. His life and work bridge the artistic currents of Scandinavia and Germany, leaving an indelible mark on the Romantic movement.

Humble Beginnings in Bergen

Dahl's origins were modest. He was born into a simple fishing family in Bergen, a bustling port city on Norway's west coast. His father, Claus Dahl, worked as a fisherman and ferryman, and the family's economic situation was often precarious. Despite these humble beginnings, young Johan Christian showed an early and remarkable aptitude for drawing. His talent did not go unnoticed; a sympathetic mentor from the Bergen Cathedral School recognized his potential.

This recognition led to him being placed as an apprentice in the workshop of Johan Georg Müller around the age of fifteen. Müller was considered the preeminent decorative painter in Bergen at the time, and under his tutelage, Dahl received his initial formal training in the craft of painting. However, Dahl himself later felt that the artistic environment and the training available in Bergen were somewhat limited, describing his education there as "mediocre." He yearned for broader horizons and a deeper understanding of fine art. A significant influence during this formative period was the educator Lyder Sagen, who encouraged Dahl's interest in history and fostered a sense of patriotism, themes that would subtly inform his later work.

Copenhagen: Academic Training and Artistic Awakening

In 1811, seeking more advanced artistic education, Dahl moved to Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark (Norway was then in a union with Denmark). This move was pivotal. He enrolled at the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, a center of artistic learning in Northern Europe. There, he studied under Professor Christian August Lorentzen, a respected painter known for his portraits, landscapes, and historical scenes.

The Academy exposed Dahl to a wider range of artistic influences. He diligently studied the works of 17th-century Dutch Golden Age landscape masters, particularly Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema, whose dramatic yet naturalistic depictions of scenery resonated deeply with him. Equally important was the influence of contemporary Danish artists. He encountered the work, and likely the person, of Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, a leading figure of the Danish Golden Age who was himself returning from studies abroad and bringing a new clarity and realism, especially influenced by his time in Rome. Dahl also absorbed the artistic atmosphere shaped by earlier Danish masters like Jens Juel. In Copenhagen, Dahl began to refine his skills, focusing increasingly on landscape painting and developing a keen eye for the effects of light and atmosphere.

The Italian Sojourn: Nature Observed

A crucial chapter in Dahl's development began in 1820 when he embarked on a journey to Italy. This trip was made possible through the support of Prince Christian Frederik of Denmark (later King Christian VIII), who recognized Dahl's burgeoning talent. Italy, particularly Rome and the Bay of Naples, was considered an essential destination for aspiring landscape painters, a place to study classical ruins and the luminous Mediterranean light that had inspired artists for centuries, including the great French master Claude Lorrain.

Dahl, however, approached Italy with a distinctly Romantic sensibility, less interested in classical idealism and more focused on the direct, unmediated experience of nature's power and beauty. He spent considerable time in the Naples area, famously witnessing and sketching eruptions of Mount Vesuvius. These experiences resulted in several dramatic paintings, including his renowned Eruption of Vesuvius (1826), which captures the terrifying sublimity of the volcanic event with remarkable immediacy. His time in Italy reinforced his commitment to outdoor sketching and the meticulous observation of natural phenomena – clouds, rock formations, light on water – which became hallmarks of his style. While in Rome, he moved within artistic circles that included figures like the celebrated Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and may have encountered members of the German Nazarene movement, such as Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius, though his own artistic path remained firmly rooted in landscape.

Dresden: A Second Home and Artistic Hub

Even before his Italian journey, Dahl had visited Dresden in 1818, and he eventually settled there, making it his primary residence for much of his adult life. In 1824, he achieved a significant professional milestone when he was appointed an extraordinary professor at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. This position solidified his standing in the German art world and provided him with a stable base for his work and influence.

Dresden was a major center of German Romanticism, and Dahl quickly became integrated into its vibrant artistic community. His most significant relationship there was with Caspar David Friedrich, the leading figure of German Romantic painting. Dahl and Friedrich became close friends, neighbors (sharing a house on the Elbe river for a period), and respected colleagues. They embarked on sketching trips together and engaged in deep artistic dialogue. While their styles remained distinct – Friedrich's work often imbued with more overt symbolism and spiritual allegory, Dahl's generally more grounded in naturalistic observation – they shared a profound reverence for nature and influenced each other's approach to landscape.

Dahl's circle in Dresden also included Carl Gustav Carus, a physician, philosopher, scientist, and talented painter in his own right. Carus, Dahl, and Friedrich formed a trio that significantly shaped the landscape painting of the era in Dresden. Dahl also interacted with other artists associated with the Dresden scene, such as Ludwig Richter. His presence enriched the city's artistic life, bringing a distinct Northern European perspective to German Romanticism.

The Romantic Vision: Style and Subject Matter

Dahl's art is quintessentially Romantic, characterized by its emotional depth, emphasis on individuality, and fascination with the power and beauty of the natural world. He excelled at capturing the specific moods of nature, often depicting dramatic weather conditions – gathering storms, the turbulent sea, the ethereal effects of moonlight, or the warm glow of sunrise and sunset. His landscapes are rarely tranquil in a classical sense; they often possess an energy, a sense of dynamism, reflecting the untamed forces of nature.

Unlike the more allegorical landscapes of Friedrich, Dahl's work generally maintains a stronger connection to observed reality. His paintings feel topographically specific, grounded in the careful studies he made directly from nature. He possessed a remarkable ability to render the textures of rock, the movement of water, the intricate forms of trees, and the ephemeral quality of clouds and light. His brushwork could be precise in details but also wonderfully free and expressive, particularly in his numerous oil sketches made outdoors.

Discovering Norway: The National Landscape

While Dahl spent much of his career abroad, his heart remained deeply connected to his homeland. Starting with his first return trip in 1826, he made several journeys back to Norway throughout his life. These trips were artistically transformative. Dahl effectively "discovered" the Norwegian landscape as a subject for high art. He travelled extensively, sketching and painting the unique and dramatic scenery of his native country: towering mountains, deep fjords, cascading waterfalls, dense forests, and the rugged coastline.

His depictions of Norway were groundbreaking. He captured the specific character of the Norwegian wilderness, its grandeur, and sometimes its harshness. Works featuring subjects like the stave churches (ancient wooden churches unique to Norway), traditional rural life, and identifiable locations like Stalheim or the Hardangerfjord played a crucial role in shaping a national artistic identity for Norway, which had recently entered a new union with Sweden (after 1814) and was undergoing a period of national awakening. Dahl's Norwegian landscapes resonated with a growing sense of national pride and cultural self-awareness.

Masterworks: Capturing Nature's Drama

Dahl's prolific output includes numerous masterpieces that exemplify his artistic vision.

The Eruption of Vesuvius (versions from the 1820s, e.g., 1826): These paintings showcase Dahl's ability to capture the sublime terror and awe-inspiring power of nature. Based on direct observation, they are dynamic compositions filled with fire, smoke, and molten lava, demonstrating his skill in rendering dramatic light and atmospheric effects.

View of Dresden by Moonlight (e.g., 1838, 1839): A recurring theme for Romantic painters, Dahl's moonlit views of his adopted city, often featuring the Augustus Bridge and the Elbe River, are exercises in atmosphere. They differ from Friedrich's similar subjects by often feeling more grounded and less overtly symbolic, focusing on the interplay of moonlight, shadow, and architectural forms.

Stalheim (e.g., 1842): This iconic view, depicting the dramatic landscape near Stalheim in Western Norway with its steep cliffs and winding valley, became one of his most famous Norwegian motifs. It perfectly encapsulates the majestic and untamed character of the Norwegian wilderness that Dahl sought to portray.

Birch Tree in a Storm (e.g., 1849): A recurring motif, the lone birch tree battling the elements often serves as a symbol of resilience and the enduring spirit of nature, perhaps even reflecting Norwegian fortitude. These works highlight Dahl's expressive brushwork and his interest in depicting movement and natural forces.

Shipwreck off the Norwegian Coast (various versions): Dahl frequently painted scenes of maritime disaster, capturing the terrifying power of the sea and the vulnerability of human endeavors against it. These works are prime examples of the Romantic sublime, evoking feelings of awe and terror.

Frederiksborg Castle (1817) and views of Copenhagen, such as Two Church Towers in Copenhagen against the Evening Sky (c. 1830), demonstrate his skill in depicting architectural subjects and cityscapes, often imbued with a specific atmospheric mood tied to the time of day or weather.

His numerous cloud studies and oil sketches made en plein air are also highly valued today, revealing his process of direct observation and his mastery of capturing fleeting effects of light and weather with remarkable freshness and spontaneity.

Influence, Teaching, and Cultural Legacy

Johan Christian Dahl's influence extended far beyond his own canvases. As a professor at the Dresden Academy, he taught and inspired a generation of students. His most significant Norwegian pupil was Thomas Fearnley, who followed closely in Dahl's footsteps as a landscape painter, traveling extensively and depicting Norwegian scenery with a similar Romantic sensibility. Dahl's pioneering work laid the foundation for subsequent Norwegian landscape painters like Peder Balke and Hans Gude, who continued to explore and celebrate the national landscape.

Beyond his artistic output, Dahl was a passionate advocate for Norwegian culture and heritage. He played an active role in the efforts to preserve Norway's unique medieval stave churches. Notably, he was instrumental in saving the Vang Stave Church, arranging for its purchase by King Frederick William IV of Prussia and its relocation to Silesia (now in Poland) when it faced demolition in Norway. He was also a key proponent for the establishment of a national art collection in Norway, contributing significantly to the founding of the National Gallery in Christiania (now Oslo). His international standing was confirmed by memberships in the art academies of Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Berlin, among others.

Personal Life: Triumphs and Tragedies

Dahl's personal life was marked by both professional success and profound personal loss. In 1820, he married Emilie von Block. Their happiness was short-lived, as Emilie died in childbirth in 1827, a devastating blow to the artist. He found love again and married his student Amalie von Bassewitz in 1830, but tragedy struck once more when Amalie also died shortly after childbirth later that same year. These successive losses of his wives, along with the deaths of several of his children in infancy or childhood, undoubtedly cast a shadow over his life and perhaps infused some of his later works with a deeper sense of melancholy or drama.

Despite these sorrows, Dahl continued to paint and teach. He maintained his deep connection to Norway through correspondence and return visits. His surviving son, Siegwald Johannes Dahl (1827–1902), born to his first wife Emilie, also became a painter, specializing initially in animal painting and later landscapes, clearly influenced by his father's legacy. Dahl remained in Dresden for the rest of his life, a respected figure in the city's cultural landscape. He passed away there on October 14, 1857, and was buried in the Elias Cemetery, though his grave was later moved.

Enduring Significance

Johan Christian Dahl occupies a unique and pivotal position in 19th-century European art. He successfully synthesized the influences of Dutch landscape tradition, Danish Golden Age clarity, and German Romantic philosophy into a style uniquely his own. While deeply integrated into the German art scene in Dresden and a close associate of Caspar David Friedrich, he never lost his distinct artistic identity or his profound connection to his Norwegian roots.

He is rightfully celebrated as the father figure of Norwegian painting, the artist who first truly captured the specific character and grandeur of the Norwegian landscape and elevated it to a subject of international artistic importance. His work not only inspired generations of Scandinavian artists but also contributed significantly to the broader European Romantic movement's fascination with untamed nature and national identity. Dahl's legacy endures in his powerful, evocative landscapes that continue to speak of the beauty, drama, and enduring spirit of the natural world.