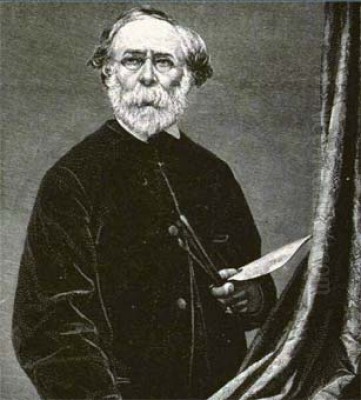

Introduction: A Bridge Between Eras

Paul Huet (1803-1869) stands as a pivotal figure in the history of French art, particularly renowned as a leading landscape painter of the Romantic era. Born and active in France throughout the 19th century, Huet carved a unique path, distinct from the prevailing Neoclassical traditions of his youth. His work is characterized by a profound emotional engagement with nature, a fascination with atmospheric effects, and a technical approach deeply influenced by British contemporaries. He masterfully blended Romantic sensibility with a keen observation of the natural world, effectively bridging the gap between the dramatic intensity of Romanticism and the burgeoning realism that would pave the way for Impressionism. His legacy lies not only in his evocative canvases but also in his role as an innovator and an influence on subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Paul Huet was born in Paris in 1803 into a family of comfortable means. His father, a prosperous cloth and linen merchant, initially envisioned a different future for his son, hoping he would pursue a career as a writer or scholar. However, the young Huet felt an undeniable pull towards the visual arts. Demonstrating his commitment at an early age, he interrupted his classical education around the age of thirteen to dedicate himself fully to painting.

His formal artistic training began under the tutelage of established figures within the French academic system. He initially entered the studio of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, a prominent painter known for his Neoclassical historical scenes. Guérin's studio was a hub of artistic activity, and it was here that Huet would form connections that would shape his career. Following his time with Guérin, Huet moved to the studio of Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, another significant painter celebrated for his large-scale historical and military subjects, often imbued with a pre-Romantic dynamism. While trained within this Neoclassical framework, Huet's artistic inclinations soon led him towards a different mode of expression, one more attuned to the direct experience of nature.

The Transformative Influence of British Landscape Painting

A crucial turning point in Huet's development came through his encounters with British art and artists. The early 19th century saw a burgeoning appreciation in France for the naturalism and atmospheric sensitivity of British landscape painting, particularly the works of John Constable and J.M.W. Turner. Constable's paintings, exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1824, caused a sensation with their fresh, direct approach to capturing the effects of light and weather.

Huet was deeply receptive to these influences. His connection became more personal and direct when, around 1820, while likely still associated with Gros's studio, he met the young English painter Richard Parkes Bonington. Bonington, though tragically short-lived (1802-1828), was a brilliant exponent of watercolor and plein air (outdoor) sketching. The two artists formed a close bond, sharing a passion for landscape.

Bonington's example was particularly formative for Huet. He introduced Huet to the fluid, transparent techniques of English watercolor, a medium perfectly suited for capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. Furthermore, Bonington's practice of sketching directly from nature outdoors encouraged Huet to move beyond studio conventions and engage more intimately with the landscape itself. Together, they embarked on sketching trips, notably to the coast of Normandy, where the dramatic cliffs, changing skies, and coastal light provided ample inspiration. This period solidified Huet's commitment to landscape and equipped him with new technical means to express his vision.

A Lifelong Friendship: Eugène Delacroix

Another significant relationship forged during Huet's formative years was his friendship with Eugène Delacroix, the towering figure of French Romantic painting. They met in 1822, likely in the studio of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, where both were students for a time. Despite their different primary subjects – Delacroix focusing on historical, literary, and exotic themes, Huet on landscape – they found common ground in the expressive intensity and emotional depth of the Romantic spirit.

Their connection developed into a deep and enduring friendship that lasted throughout their lives. They shared artistic ideas and provided mutual support. Evidence of their collaboration exists: Huet is known to have painted parts of the landscape background for Delacroix's portrait of Louis-Auguste Schwiter (c. 1826-30), now housed in the National Gallery, London. This friendship placed Huet firmly within the circle of leading Romantic artists and reinforced his departure from the cooler rationalism of Neoclassicism. Delacroix admired Huet's dedication to landscape and his ability to convey nature's power and poetry.

Forging a Path: Romantic Landscape Takes Root

By the late 1820s and early 1830s, Paul Huet was establishing himself as a distinct voice in French landscape painting. He moved away from the idealized, historical landscapes favored by the Neoclassical school, represented by artists like Jacques-Louis David and his followers, including Huet's own early teachers Guérin and Gros to some extent. Instead, Huet sought to capture the specific character and mood of the French countryside, infused with Romantic feeling.

His breakthrough came at the Paris Salon of 1831. This exhibition marked a significant success for the young artist. He submitted an impressive group of nine oil paintings and four watercolors. Among the works exhibited were titles that hinted at his Romantic preoccupations: Rouen Beach, Sunset Fog, and The Flood at Saint-Cloud. These works showcased his developing style, characterized by dynamic compositions, attention to atmospheric conditions, and an often dramatic rendering of natural phenomena. His success at this Salon helped solidify his reputation as a leading proponent of the new, Romantic approach to landscape.

Masterworks: Capturing Nature's Drama and Subtlety

Throughout his long career, Paul Huet produced a significant body of work, exploring various landscapes and employing different media. Several works stand out as particularly representative of his artistic vision and technical skill.

View of Rouen: Perhaps one of Huet's most ambitious early projects was the General View of Rouen, created around 1831-1833. Originally conceived as a massive panorama, reportedly over thirteen feet long, for the popular Diorama Montesquieu in Paris, it depicted the city from a commanding viewpoint. Inspired partly by Constable's handling of skies and atmosphere, the work featured dramatic cloud formations and strong contrasts of light and shadow, imbuing the urban landscape with Romantic grandeur. Unfortunately, the original Diorama painting faced a troubled fate. Financial difficulties led to the seizure of the work, and it was ultimately destroyed in a fire at the Théâtre du Cirque-Olympique in 1835. However, preparatory studies, sketches, and possibly a smaller studio version survive, testifying to the scale and artistic merit of this significant undertaking.

Environs de Rouen: Reflecting his early engagement with the Normandy region, works like Environs de Rouen (c. 1825-26) capture the specific character of the local landscape. These early studies often served as inspiration for later works, including a series of lithographs titled Six Seascapes Lithographed from Nature, demonstrating his interest in exploring different printmaking techniques alongside painting. These works show his developing ability to render the textures and light of the Norman countryside.

Brans Pass: Painted during the winter of 1838, Brans Pass (or The Pass of Brans) showcases Huet's mastery of watercolor and his sensitivity to subtle atmospheric effects. Depicting a tranquil valley scene in the South of France, the work is remarkable for its delicate handling of light and color. Huet uses soft washes and nuanced tones to convey the quiet beauty and specific quality of light in the mountain landscape. Often considered a high point in his watercolor practice, it demonstrates his ability to capture intimacy and serenity as effectively as drama.

Forest of Fontainebleau: Hunters: Dating from the 1860s, this later work exemplifies Huet's continued engagement with the Forest of Fontainebleau, a location that would become central to the Barbizon School painters. Forest of Fontainebleau: Hunters reveals his mature style, characterized by a keen observation of natural detail – the textures of bark, foliage, and earth – combined with a sophisticated handling of dappled sunlight filtering through the trees. It shows his enduring ability to balance naturalistic rendering with a sense of atmosphere and narrative suggestion.

The Essence of Huet's Style: Romanticism Meets Nature

Paul Huet's artistic style is a compelling synthesis of Romantic fervor and careful observation of the natural world. He was not content merely to transcribe appearances; he sought to convey the emotional impact of the landscape, its power, mystery, and beauty.

His Romanticism is evident in his frequent depiction of dramatic weather – turbulent skies, gathering storms, shafts of sunlight breaking through clouds, and the effects of mist and floods. He used strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten the emotional intensity and create a sense of dynamism within the scene. His compositions often employ low horizons, emphasizing the vastness of the sky, a characteristic shared with some Dutch Golden Age masters like Jacob van Ruisdael, as well as his British contemporaries.

Yet, this Romantic drama was always grounded in naturalism. Huet was a dedicated observer of nature's specifics. His numerous outdoor sketches, made during his travels, provided the raw material for his studio paintings. He paid close attention to the particularities of place, the structure of trees, the formation of rocks, and the quality of light at different times of day and under various weather conditions. This commitment to observation lends authenticity and conviction to even his most dramatic canvases.

Huet's technical versatility was also a hallmark of his art. While accomplished in oil painting, he was a particularly gifted watercolorist, mastering the transparent washes and fluid application favored by the English school. He was also an adept printmaker, exploring the possibilities of etching and lithography to disseminate his landscape visions more widely. This multi-faceted approach allowed him to explore different aspects of landscape representation, from broad atmospheric effects to fine linear detail.

Travels and the Importance of Plein Air

Like many landscape painters of his generation, Paul Huet was an avid traveler. He believed in the importance of direct experience and observation, spending considerable time sketching outdoors (en plein air) in various regions of France. Normandy, with its dramatic coastline and changeable weather, was a recurring destination throughout his career. He also traveled extensively in the South of France, capturing the unique light and landscapes of Provence and the mountainous regions like the Auvergne.

The Forest of Fontainebleau, near Paris, was another crucial site for Huet. He worked there frequently, drawn to its ancient trees, rocky outcrops, and varied woodland scenery. While the final, often large-scale paintings were typically completed in the studio, his numerous oil sketches and watercolors made on location were essential to his process. These studies captured the immediate sensations of light, color, and atmosphere, which he would then translate and elaborate upon in his finished works. This practice of outdoor sketching connected him to the emerging Barbizon School, even though he remained somewhat independent of the group itself. His travels provided a rich inventory of motifs and a deep understanding of the diverse character of the French landscape.

Connections to Barbizon and Corot

Paul Huet is often considered an important precursor to the Barbizon School, the group of painters who, from the 1830s onwards, gathered near the village of Barbizon to paint the Forest of Fontainebleau directly from nature. While Huet shared their commitment to landscape and naturalistic observation, his style generally retained a more pronounced Romantic emotionalism compared to the often quieter realism of core Barbizon figures like Théodore Rousseau or Jean-François Millet.

However, Huet certainly interacted with artists associated with Barbizon. He frequented the same locations, particularly Fontainebleau, and shared artistic concerns. He maintained connections with painters like Rousseau, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, and Jules Dupré, likely encountering them in Paris or during excursions to the forest. His emphasis on capturing the specific moods and effects of French nature paved the way for their more systematic exploration of the Fontainebleau landscape.

His relationship with Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot is particularly noteworthy. Corot, another giant of 19th-century French landscape painting, also bridged Romanticism and Realism. Huet and Corot knew each other and sometimes worked in the same areas, such as the forests around Paris and Versailles. While their temperaments and styles differed – Corot often favoring a more lyrical and silvery tonality – they shared a dedication to observing light and atmosphere. Corot's developing realism likely influenced Huet, while Huet's earlier embrace of Romantic landscape may have resonated with Corot. Huet also associated with marine painters like Eugène Isabey and Charles Mozin, sharing sketching sessions on the Normandy beaches, further expanding his network within the landscape painting community.

Later Career, Recognition, and Politics

Paul Huet continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, adapting his style while remaining true to his core vision. He participated regularly in the Paris Salons, the main venue for artists to display their work and gain recognition. His dedication and talent earned him official accolades over the years. He was awarded a gold medal at the Salon of 1848, a year of significant political upheaval in France. He also received awards at major international exhibitions, including the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855 and again in 1867, confirming his established position within the French art world.

Beyond his artistic activities, Huet held Republican political sympathies. While not overtly political in most of his landscape paintings, his engagement with the political currents of his time reflects a broader awareness characteristic of many Romantic figures who believed in individual liberty and social progress. His career spanned a period of immense change in France, from the Bourbon Restoration through the July Monarchy, the Second Republic, and the Second Empire, and his consistent artistic production amidst these shifts underscores his dedication to his craft.

Legacy: A Romantic Visionary's Enduring Influence

Paul Huet's death in 1869 marked the end of a significant career that spanned much of the evolution of 19th-century French landscape painting. His primary legacy lies in his role as a key figure in establishing Romantic landscape painting in France. He successfully challenged the dominance of Neoclassical conventions, championing a more personal, emotional, and observation-based approach to depicting nature.

His unique synthesis of French Romantic sensibility with the techniques and atmospheric concerns of British landscape painting created a powerful and influential style. He demonstrated how landscape could be a vehicle for profound emotional expression, capturing both the sublime power and the intimate beauty of the natural world. His mastery of light, shadow, and weather effects set a high standard for landscape representation.

Huet's influence extended to subsequent generations. His work served as an important precedent for the painters of the Barbizon School, who further developed the practice of direct painting from nature. Moreover, his emphasis on capturing fleeting atmospheric effects and his increasingly free brushwork in some later works can be seen as anticipating aspects of Impressionism. Artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, who revolutionized painting later in the century, would have been aware of Huet's contributions to landscape and his exploration of light and atmosphere. His works continue to be held in major museum collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, ensuring his contribution to art history is recognized and studied.

Conclusion: Nature's Poet

Paul Huet remains a vital figure in the narrative of French art. He was more than just a landscape painter; he was a poet of nature, capable of translating its myriad moods onto canvas and paper. Through his deep engagement with the French countryside, his absorption of international influences, and his unwavering commitment to his personal vision, he carved out a unique space within the Romantic movement. His evocative depictions of storms, forests, coasts, and valleys continue to resonate with viewers today, reminding us of the power and beauty of the natural world as seen through the eyes of a master. His role as an innovator, a bridge between artistic movements, and a profound interpreter of landscape secures his lasting importance in the history of art.