John Cooke Bourne stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century British art, not primarily for grand historical canvases or society portraits, but for his meticulous and evocative documentation of one of the era's most transformative forces: the railway. Born in London in 1814, Bourne lived until 1896, witnessing the zenith of the Industrial Revolution and the profound impact of steam locomotion on the British landscape, economy, and society. Trained initially as an engraver and later mastering the art of lithography, Bourne applied his considerable artistic skill to capturing the monumental engineering feats and the often-chaotic process of railway construction, leaving behind a visual record that remains invaluable to historians and art lovers alike.

Bourne's work occupies a unique intersection between art, engineering, and social history. He was more than a mere topographical draughtsman; he possessed a keen eye for composition, light, and atmosphere, elevating his depictions of cuttings, tunnels, viaducts, and stations beyond simple records. He captured the sublime power of industry reshaping nature, the human toil involved, and the emergence of a new kind of landscape where iron and steam met earth and sky. His legacy rests largely on two major published collections of lithographs, which cemented his reputation as the foremost artistic chronicler of Britain's "Railway Mania."

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Cooke Bourne entered the world in London, a city on the cusp of unprecedented growth fueled by industrial innovation. His artistic inclinations led him, in 1828, to an apprenticeship under the respected engraver John Pye. Pye was known for his skillful interpretations of other artists' work, notably his engravings after the celebrated landscape painter J.M.W. Turner. This connection, even if indirect, placed the young Bourne within the orbit of Britain's leading artistic currents, particularly the Romantic fascination with landscape, light, and atmosphere, elements that would subtly inform his later work.

While engraving provided a foundation in precision and line work, Bourne also absorbed influences from the flourishing school of English watercolour painting. Artists like Thomas Girtin, a tragically short-lived contemporary of Turner known for his broad, atmospheric washes and mastery of landscape, and John Sell Cotman, celebrated for his structural clarity and pattern-making in architectural and landscape subjects, likely shaped Bourne's developing aesthetic. He learned to see the pictorial possibilities in structure and scenery, a skill he would later adapt to the seemingly utilitarian subject of railway engineering.

Bourne's training instilled in him a respect for classical artistic principles, emphasizing composition, balance, and careful observation. However, rather than applying these skills solely to traditional subjects, he turned his attention to the dynamic, rapidly changing world around him. The rise of the railways presented a novel and compelling theme – a testament to human ingenuity and ambition, dramatically altering the familiar British countryside. This fusion of classical training and contemporary subject matter would become a hallmark of his distinctive style. He also became highly proficient in lithography, a relatively new printing technique invented by Alois Senefelder that allowed for greater tonal subtlety and a more direct translation of the artist's drawing onto the printing plate compared to engraving.

The London and Birmingham Railway: A Monumental Record

Bourne's first major triumph came with his series documenting the construction of the London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR). Engineered by the brilliant Robert Stephenson, the L&BR was one of Britain's first long-distance, inter-city railway lines, a project of immense scale and complexity that captured the public imagination. Commencing work in the mid-1830s, Bourne immersed himself in the project, sketching tirelessly along the route as it snaked its way from the capital towards the industrial heartlands.

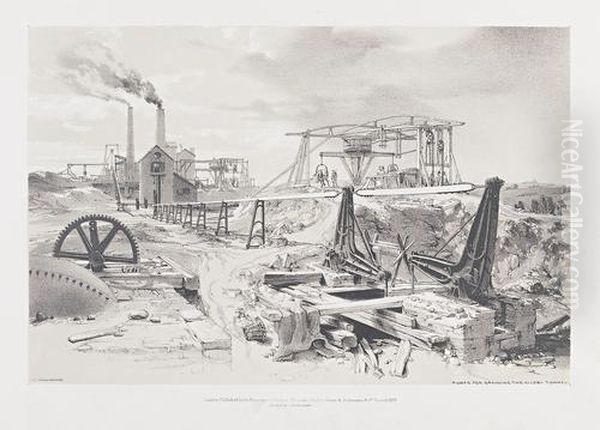

The resulting publication, Drawings of the London & Birmingham Railway, appeared in 1839, with lithographs executed by Bourne himself based on his on-site sketches. The collection was remarkable for its comprehensive scope, depicting not just the finished structures but the raw, often chaotic process of construction. Viewers could witness the vast excavations of cuttings like the one at Tring, teeming with navvies and their rudimentary equipment, the challenging tunnelling work at Kilsby, battling quicksand and water ingress, and the erection of bridges and viaducts.

Bourne's artistic approach was multifaceted. He rendered engineering details with impressive accuracy, satisfying the technical interest in the project. Yet, he simultaneously infused the scenes with a sense of drama and atmosphere. His use of light and shadow, the framing of structures within the landscape, and the inclusion of human figures – labourers, engineers, onlookers – brought the monumental undertaking to life. Works like the view of the grand Doric Euston Arch, the railway's London terminus, showcased the architectural ambitions associated with the new mode of transport, linking it to classical precedents.

The L&BR series demonstrated Bourne's ability to find beauty and grandeur in industrial activity. He didn't shy away from the disruption caused by construction but framed it within a picturesque sensibility, often using trees and foliage to soften the hard edges of engineering. The lithographs were not just records; they were carefully composed images that conveyed the awe-inspiring nature of the railway's creation, capturing a pivotal moment in British history through the lens of a skilled and sensitive artist. The publication was a significant achievement, establishing Bourne as a leading practitioner of topographical and industrial art.

Charting the Great Western: Brunel's Vision

Following the success of his L&BR portfolio, Bourne turned his attention to another titan of the railway age: Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Great Western Railway (GWR). Known for its ambitious engineering, distinctive architectural style, and controversial broad gauge track, the GWR represented a different, perhaps more flamboyant, approach to railway building compared to the L&BR. Bourne undertook the task of documenting this line, culminating in the publication of The History and Description of the Great Western Railway in 1846.

This volume was a collaborative effort, with historical and descriptive text provided by the antiquarian John Britton. Bourne, however, was responsible for the stunning lithographic plates that formed the core of the work. He captured the unique character of the GWR, from the neoclassical grandeur of Paddington Station's original buildings to the engineering marvels along the line, such as Brunel's elegant Maidenhead Bridge with its remarkably flat brick arches spanning the Thames, and the formidable Box Tunnel, then the longest railway tunnel in the world.

Bourne's style continued to blend technical fidelity with artistic interpretation. His depictions of GWR structures often emphasized their integration into the landscape, sometimes presenting an almost pastoral vision despite the industrial subject matter. He captured the scale of Brunel's designs, the solidity of the masonry, and the sense of power embodied by the locomotives and infrastructure. Compared to the L&BR series, the GWR collection perhaps focused slightly more on the completed railway in operation, showcasing trains traversing the landscape and the finished stations serving passengers.

Through works like the GWR volume, Bourne helped shape the public perception of railways. His images presented them not merely as utilitarian transport systems but as aesthetically significant additions to the national landscape, monuments to British ingenuity and progress. He documented Brunel's distinctive architectural flourishes and engineering solutions, providing a visual counterpoint to the often-heated debates surrounding the GWR's gauge and construction methods. Like his earlier work, the GWR series remains a vital resource for understanding this crucial railway line and the era it embodied.

Artistic Style: Precision, Atmosphere, and the Picturesque

John Cooke Bourne's artistic style is characterized by a remarkable synthesis of seemingly disparate elements. At its core lies a commitment to accuracy and detailed observation, essential for documenting complex engineering projects. His training as an engraver under John Pye undoubtedly honed his ability to render precise lines and technical features, a skill evident in his depictions of bridges, tunnels, earthworks, and station architecture. Viewers could understand the construction methods and the scale of the undertakings through his clear, informative drawings.

However, Bourne was far more than a technical illustrator. He possessed a strong sense of pictorial composition and atmosphere, drawing heavily on the British landscape tradition. His work often incorporates elements of the Picturesque aesthetic, popularised by figures like William Gilpin, which valued irregularity, texture, and the harmonious integration of man-made structures within natural settings. Bourne frequently used framing devices like trees or archways, employed dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, and paid careful attention to weather effects and the quality of light to enhance the mood of his scenes.

This approach allowed him to romanticize the often-brutal reality of railway construction. While depicting the immense labour involved, as seen in the Tring Cutting, the overall impression is often one of heroic endeavour and eventual harmony between industry and nature. He softened the visual impact of raw earthworks and masonry with foliage and atmospheric effects, suggesting that the railways, despite their novelty and scale, could become a natural and enduring part of the British scene. This contrasts with the approach of some earlier artists who depicted industry, like Philip James de Loutherbourg in his dramatic Coalbrookdale by Night, which emphasized fire and infernal power, or Joseph Wright of Derby, who focused on the scientific and intellectual aspects of the industrial age.

Bourne's mastery of lithography was crucial to his style. The medium allowed for rich tonal variations, from deep shadows to delicate highlights, enabling him to convey texture and atmosphere effectively. His work stands comparison with other skilled lithographers of the period, such as Thomas Shotter Boys, known for his picturesque views of London and Paris street scenes, though Bourne's focus on large-scale industrial construction was unique. He successfully translated the weight of stone, the texture of earth, and the ephemeral quality of steam and smoke into compelling printed images.

Beyond Britain: Documenting the Kyiv Bridge

Bourne's reputation extended beyond British railway projects. In 1847, he was invited by the prominent engineer Charles Vignoles to travel to the Russian Empire (specifically, modern-day Ukraine) to document the construction of a major new bridge across the Dnieper River at Kyiv (then often spelled Kiev). Vignoles, an accomplished railway engineer himself who had worked on early lines in Britain and Ireland, was responsible for designing this ambitious suspension bridge, a significant feat of engineering in its time.

This commission marked an important expansion of Bourne's horizons, taking his skills to an international stage. He spent considerable time in Kyiv, producing drawings and watercolours of the bridge's construction process. These works, similar in approach to his railway series, captured the various stages of building the piers and erecting the chains for the suspension structure, again blending technical detail with atmospheric depiction of the location and the human activity involved.

Intriguingly, during his time in Kyiv, Bourne also experimented with the relatively new medium of photography. It is recorded that he took calotype photographs, primarily portraits of the engineers and workers involved in the bridge project. This early adoption of photography alongside his traditional drawing practice demonstrates Bourne's engagement with new technologies, not just as subjects for his art but as tools for documentation. While his primary legacy remains his lithographs, his photographic work in Kyiv represents a fascinating, though less well-known, aspect of his career, placing him among the pioneers using photography for engineering project records. The Kyiv bridge plates were later published, further cementing his reputation for documenting major engineering works.

Bourne in the Context of His Time: Art, Industry, and Society

John Cooke Bourne worked during a period of intense artistic and social ferment in Britain. The Romantic movement, with its emphasis on nature, emotion, and the sublime, was reaching its zenith, exemplified by the dramatic landscapes of J.M.W. Turner and the pastoral scenes of John Constable. While Bourne shared the Romantics' interest in landscape and atmosphere, his subject matter – the intrusion of heavy industry into that landscape – set him apart. He navigated a path between celebrating industrial progress and acknowledging its impact on the traditional environment.

His detailed, observational style also connects him to the strong British tradition of topographical and architectural drawing. Artists like Augustus Pugin were meticulously documenting Gothic architecture, albeit with a focus on revivalism rather than modern engineering. Bourne applied a similar level of detail to contemporary structures, creating a valuable record for future generations. His work provided a visual narrative of the Industrial Revolution that complemented written accounts and statistical data.

The railway itself was a potent symbol in the nineteenth century, representing progress, speed, national unity, and economic power, but also social disruption, environmental change, and the perceived threat to traditional ways of life. Bourne's work inevitably engaged with these themes. His images often carried an implicit endorsement of the railway project, presenting it as a heroic and ultimately beneficial enterprise. They served, perhaps unintentionally, as effective publicity for the railway companies and the engineers, like Stephenson and Brunel, who built them.

The "Railway Mania" of the mid-1840s saw frenzied investment and speculation in railway projects. Bourne's GWR publication appeared at the height of this boom. However, the subsequent crash and the gradual normalization of railway travel perhaps lessened the public appetite for heroic depictions of railway construction. While later artists like William Powell Frith would capture the social scene of The Railway Station (1862), focusing on passengers and human drama, Bourne's primary contribution was documenting the physical creation of the network itself during its pioneering phase. His focus remained steadfastly on the engineering and its interaction with the landscape.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Following his major railway publications and the Kyiv bridge project, Bourne continued to work as an artist and lithographer, though his later output is generally considered less impactful than his celebrated railway series. The intense public fascination with the construction of railways perhaps waned as the network became an established part of British life. While he produced other works, including landscapes and architectural views, none achieved the same level of recognition as his L&BR and GWR portfolios.

Despite this, John Cooke Bourne's legacy is secure. His railway lithographs are now recognized as masterpieces of industrial art and invaluable historical documents. They offer a unique window into the ambition, scale, and visual character of the early railway age in Britain. His ability to combine technical accuracy with genuine artistic sensibility created images that are both informative and aesthetically compelling. He demonstrated that industrial subjects could be treated with the same seriousness and artistry traditionally reserved for landscape, portraiture, or historical scenes.

Modern historians and art critics appreciate Bourne's work for its nuanced depiction of the relationship between technology and nature. His images capture the sublime power of engineering while often retaining a sense of picturesque beauty, reflecting the complex attitudes of the era towards industrialization. He documented not just the structures themselves but also the human effort involved, providing glimpses of the navvies, engineers, and surveyors who built the lines. His high level of draughtsmanship led some commentators, like F.D. Klingender, to rank him highly among the landscape artists of his day, irrespective of his specific subject matter.

Long after his death in 1896, Bourne's work continues to be studied and admired. His lithographs are frequently reproduced to illustrate histories of the Industrial Revolution and railway development. Artists who later tackled industrial or transport themes, even much later figures like Terence Cuneo known for his dynamic paintings of steam locomotives, owe a debt to pioneers like Bourne who first established industry as a valid subject for serious art. He remains the pre-eminent visual chronicler of the birth of the British railway system.

Conclusion: A Visionary Documentarian

John Cooke Bourne occupies a vital place in the history of British art and the documentation of the Industrial Revolution. As a skilled engraver and a master lithographer, he possessed the technical prowess to record the complex engineering feats of the early railway age with remarkable clarity. Yet, his contribution transcends mere technical illustration. Influenced by the Romantic landscape tradition and possessing a sophisticated compositional sense, he imbued his depictions of railway construction with atmosphere, drama, and a unique aesthetic sensibility.

His major works, particularly the series on the London & Birmingham and Great Western Railways, stand as unparalleled visual records of these transformative projects. They capture the heroic scale of the undertakings, the challenges faced by engineers like Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the human labour involved, and the profound impact of the iron road on the British landscape. Bourne's art navigated the complex relationship between burgeoning industry and the natural world, often presenting a vision of potential harmony through a picturesque lens.

While perhaps not achieving the widespread fame of some of his purely landscape-focused contemporaries like Turner or Constable during his lifetime, Bourne's focused dedication to chronicling the railway revolution produced a body of work of immense historical and artistic significance. He demonstrated that art could engage directly with the defining technological and social changes of its time, creating images that were both beautiful and informative. John Cooke Bourne remains a key figure for understanding how nineteenth-century Britain saw itself and its monumental achievements, forever capturing the power and the poetry of the age of steam.