Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1501) stands as one of the most versatile and innovative figures of the Italian Renaissance. Born in Siena, a city with a rich artistic heritage distinct from that of Florence, Martini embodied the period's ideal of the "Uomo Universale" or Universal Man. His prodigious talents spanned painting, sculpture, architecture, and, perhaps most significantly, civil and military engineering. His theoretical writings, particularly his treatise on architecture and engineering, would influence generations of artists and builders, including luminaries like Leonardo da Vinci. This exploration delves into the multifaceted career of Francesco di Giorgio Martini, examining his artistic development, his groundbreaking engineering work, his influential theories, and his lasting impact on Renaissance art and technology.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Siena

Francesco di Giorgio Martini was baptized on September 23, 1439, in Siena. His early training is believed to have been under the painter and sculptor Lorenzo di Pietro, better known as Vecchietta, a prominent Sienese artist who himself was a multifaceted talent. Siena, though politically and economically less dominant than Florence, possessed a vibrant artistic culture that had produced masters like Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers in earlier centuries. By Francesco's time, Sienese art, while still retaining some of its Gothic elegance and decorative qualities, was increasingly engaging with the humanist and naturalistic innovations emanating from Florence and other Italian centers.

Martini's early career was primarily focused on painting and sculpture. He is documented as a painter from 1464. His style in these early years reflects the Sienese tradition, characterized by a lyrical grace, an emphasis on line, and often a rich color palette. However, one can also discern an emerging interest in perspective and anatomical accuracy, likely stimulated by developments in Florence and the work of artists like Piero della Francesca, whose mathematical approach to perspective was profoundly influential throughout Italy.

The Painter and Sculptor

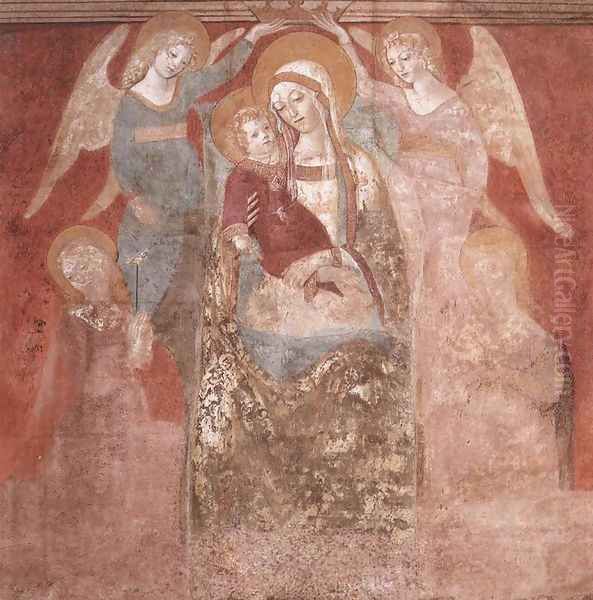

As a painter, Francesco di Giorgio Martini belonged to the Sienese School. His works often display a delicate sensibility and a keen observational skill. One of his most notable early paintings is the Coronation of the Virgin (1472), now housed in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. This work, while rooted in Sienese conventions, shows a sophisticated handling of space and a gentle humanity in its figures. Another significant painting, and his only signed panel, is the Nativity with Saints Bernard and Thomas Aquinas (c. 1475), also in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. This piece is remarkable for its complex composition, its atmospheric landscape, and the expressive intensity of its figures. It demonstrates Martini's growing mastery of perspective and his ability to convey deep religious feeling.

His paintings were also influenced by contemporaries like Luca Signorelli, known for his dynamic figures and dramatic compositions, and perhaps by Florentine artists such as Andrea del Verrocchio and Alessio Baldovinetti, whose workshops were crucibles of innovation in painting and sculpture. Martini's engagement with these broader artistic currents enriched his Sienese foundations.

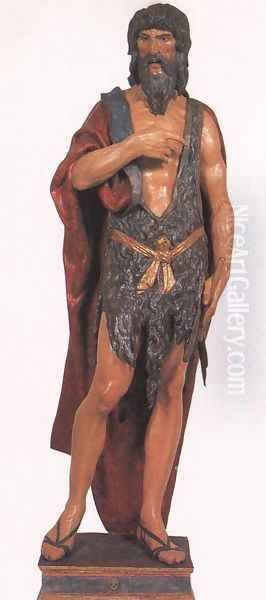

In sculpture, Martini demonstrated equal skill. He created a notable wooden statue of St. John the Baptist early in his career. More significantly, he produced a series of bronze angels for the high altar of the Siena Cathedral between 1495 and 1497. These angels are celebrated for their elegant forms and expressive power, showcasing his mastery of bronze casting, a technically demanding medium. He also produced bronze reliefs, such as a Lamentation over the Dead Christ, which shows the influence of Donatello's dramatic intensity and Piero della Francesca's compositional clarity. He is also credited with creating a model for the dome (tiburio) of Milan Cathedral around 1490, a testament to his growing reputation as an architectural consultant.

A significant aspect of his early artistic life was his partnership with another Sienese artist, Neroccio de' Landi. They collaborated from around 1468 to 1475, sharing a workshop and producing a variety of works, including altarpieces and cassone panels. Their styles, while distinct, complemented each other. This partnership, however, eventually dissolved due to disagreements, reportedly culminating in a lawsuit.

The Call to Urbino: Architect to Federico da Montefeltro

A pivotal moment in Francesco di Giorgio Martini's career came in the mid-1470s when he was summoned to Urbino to serve Duke Federico da Montefeltro. Federico was one of the most enlightened patrons of the Renaissance, a renowned condottiero (mercenary captain) and a cultivated humanist. His court at Urbino became a vibrant center of art, learning, and culture, attracting talents from across Italy and beyond. Artists like Piero della Francesca, the Flemish painter Justus van Ghent, and the Spanish painter Pedro Berruguete were active at Urbino during this period.

At Urbino, Martini's focus shifted decisively towards architecture and military engineering. While Luciano Laurana is credited with the initial design and much of the early construction of the magnificent Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, Francesco di Giorgio Martini played a crucial role in its later phases, particularly after Laurana's departure around 1472. Martini contributed to the palace's engineering aspects, its fortifications, and possibly some of its interior decorative schemes and service areas. His practical ingenuity was invaluable in completing this complex and ambitious project.

He is also credited with the design of the Church of San Bernardino degli Zoccolanti, located just outside Urbino. This church, intended as a mausoleum for Duke Federico and his successors, is a remarkable example of Renaissance architecture, characterized by its harmonious proportions, classical detailing, and serene atmosphere. Its centralized plan and elegant dome reflect the architectural ideals of the period, influenced by figures like Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti.

The Master Military Engineer

It was in the realm of military engineering that Francesco di Giorgio Martini truly excelled and gained widespread fame. The 15th century was a period of significant change in warfare, largely due to the increasing effectiveness of gunpowder artillery. Traditional medieval fortifications with high, thin walls were becoming obsolete. Martini was at the forefront of developing new defensive systems capable of withstanding cannon fire and employing artillery offensively.

For Federico da Montefeltro, and later for other patrons, Martini designed and supervised the construction or modernization of an astonishing number of fortresses – nearly seventy are attributed to him, many located within the Duchy of Urbino and surrounding territories in the Marche region. Notable examples include the Rocca Ubaldinesca at Sassocorvaro, the Rocca di Mondavio, and fortifications at Cagli, Fossombrone, and Gubbio.

His designs were innovative, featuring lower, thicker walls, often with angled or rounded bastions (trace italienne or star fort precursors) to deflect cannonballs and provide flanking fire. He incorporated gun platforms, casemates for protected artillery positions, and complex systems of outworks. He understood the importance of a layered defense and the strategic placement of fortifications to control territory. One of his more unusual, though historically attested, contributions was the invention or development of landmines. His expertise was sought after throughout Italy; he advised on fortifications for the King of Naples and other rulers.

The Theorist: Trattato di Architettura Civile e Militare

Francesco di Giorgio Martini's most enduring intellectual legacy is arguably his Trattato di Architettura Civile e Militare (Treatise on Civil and Military Architecture). This was not merely a theoretical text but a practical manual, richly illustrated with his own exquisite drawings. He worked on various versions of this treatise from the 1470s until his death. It compiled his vast knowledge gleaned from studying ancient Roman sources, particularly the writings of Vitruvius (whose De Architectura was rediscovered and avidly studied during the Renaissance), and his own extensive practical experience.

The Trattato is a comprehensive work covering a wide range of topics. In civil architecture, Martini discussed principles of urban planning, the design of palaces, churches, and other public buildings, and the importance of proportion and harmony. He famously explored the analogy between architecture and the human body, a concept derived from Vitruvius, using human proportions as a basis for architectural design. He believed that buildings, like the human form, should exhibit symmetry, balance, and a harmonious relationship between their parts.

The sections on military architecture were particularly groundbreaking, codifying many of the innovations he had implemented in his fortress designs. He provided detailed plans and explanations for various types of fortifications, siege engines, and artillery. His understanding of ballistics and the effects of gunpowder weapons was remarkable for his time.

Furthermore, the Trattato included extensive sections on engineering, particularly hydraulics and mechanics. Martini designed and illustrated a wide array of machines, including watermills, windmills, pumps, cranes, and various military devices. His drawings of these machines are not only technically proficient but also aesthetically pleasing, demonstrating his skill as a draftsman. These designs often improved upon existing technologies or proposed novel solutions to engineering problems. The treatise circulated in manuscript form and had a profound influence on subsequent architects and engineers, most notably Leonardo da Vinci, who owned a copy and annotated it.

Later Career and Engineering Feats

After the death of Duke Federico da Montefeltro in 1482, Francesco di Giorgio Martini continued to work for his son, Guidobaldo. He also undertook commissions in other parts of Italy. He was called to Naples to serve King Alfonso II (then Duke of Calabria) as a military architect and engineer from around 1491 to 1495, where he designed fortifications and advised on military matters. His expertise was highly valued in a politically turbulent Italy where warfare was frequent.

Martini also maintained his connections with his native Siena. He was appointed city architect and engineer, a role in which he was responsible for various public works. One of his significant contributions to Siena was his work on the city's unique and complex system of underground aqueducts, known as the bottini. These ancient tunnels supplied water to the city's fountains and cisterns, and Martini was involved in their maintenance and extension, a challenging feat of hydraulic engineering. He also designed the Maccerato Bridge in Siena.

His reputation as an architectural consultant led him to be consulted on major projects, such as the design of the dome (tiburio) for Milan Cathedral in 1490. He traveled to Milan and Pavia, where he likely interacted with other leading architects and engineers of the day, including Donato Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci, who were also involved in the Milan Cathedral project.

Interaction with Leonardo da Vinci

The relationship between Francesco di Giorgio Martini and Leonardo da Vinci is a fascinating aspect of Renaissance intellectual history. The two men undoubtedly knew each other and respected each other's work. Leonardo owned a copy of Martini's Trattato and studied it carefully, as evidenced by his annotations in the margins. Both were polymaths with a keen interest in mechanics, engineering, and the scientific principles underlying art and architecture.

They are known to have met, notably in Pavia in 1490 when both were consulted on the construction of the cathedral there, and possibly in Piombino. Martini's work, particularly his designs for machines and his theories on military architecture, clearly influenced Leonardo. Conversely, it is possible that Leonardo's own investigations into anatomy and mechanics may have stimulated Martini's thinking. Some of Martini's later manuscript drawings, such as a study of an Etruscan Tomb (now in the Louvre), show a dynamism and observational acuity that resonates with Leonardo's style. Their shared interest in Vitruvius and the application of mathematical principles to design created a common ground for intellectual exchange.

Artistic Style and Evolution: From Sienese Painter to Renaissance Engineer

Francesco di Giorgio Martini's artistic style underwent a significant evolution throughout his career, reflecting his diverse talents and changing professional focus. He began as a painter and sculptor firmly rooted in the Sienese tradition, characterized by its elegant linearity, decorative richness, and often conservative approach compared to the more radical innovations of Florence. His early paintings, like the Coronation of the Virgin, show a mastery of this Sienese idiom, albeit with an increasing awareness of perspective and volume.

His exposure to the humanist court of Urbino and his deep engagement with classical antiquity, particularly through Vitruvius, profoundly shaped his development. As he increasingly focused on architecture and engineering, his approach became more analytical and scientific. His architectural designs, such as the Church of San Bernardino, demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of classical forms, proportion, and spatial harmony, moving beyond purely regional styles to embrace the broader ideals of Renaissance classicism.

In his military architecture, Martini was a true innovator. His designs were driven by functional necessity and a pragmatic understanding of the new realities of gunpowder warfare. This led to a new aesthetic of fortification, characterized by powerful, geometric forms that were both imposing and efficient.

His Trattato represents the culmination of his intellectual and artistic journey. The drawings within it are not merely technical illustrations but works of art in themselves, displaying a clarity of line, a precision of detail, and an elegance of presentation that reflect his training as a painter. His ability to visualize and represent complex three-dimensional structures and mechanical systems was exceptional. He effectively synthesized the empirical knowledge of a practicing engineer with the theoretical framework of a humanist scholar.

Legacy and Influence

Francesco di Giorgio Martini's influence on subsequent generations of artists, architects, and engineers was substantial, though perhaps not as widely recognized in popular accounts of the Renaissance as that of some of his Florentine contemporaries. His Trattato di Architettura Civile e Militare, even in manuscript form, was a vital source of knowledge and inspiration.

Leonardo da Vinci, as mentioned, was a direct beneficiary of Martini's work. Donato Bramante, a key figure in the High Renaissance and the original architect of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, was also likely influenced by Martini, particularly during their time in Milan and Urbino. Other architects and theorists who drew upon Martini's ideas include Giuliano da Sangallo and his brother Antonio da Sangallo the Elder, both prominent Florentine architects who also specialized in military constructions, and Baldassare Peruzzi, another Sienese artist who became a leading architect in Rome. Even later figures like Vincenzo Scamozzi, a prominent theorist and architect of the late 16th century, acknowledged Martini's contributions.

His innovations in military architecture laid the groundwork for the development of the bastion fort system (trace italienne) that would dominate European military engineering for centuries. His emphasis on the integration of art and science, theory and practice, exemplified the Renaissance ideal and paved the way for future advancements. He demonstrated that an artist could also be a scientist and an engineer, and that these disciplines could enrich and inform one another.

Francesco di Giorgio Martini died in Siena in late 1501, leaving behind a rich legacy of built works, artistic creations, and influential writings. He was a pivotal figure in the transition from the Early to the High Renaissance, a man whose intellectual curiosity and practical ingenuity knew few bounds. His life and work offer a compelling testament to the extraordinary creativity and versatility that characterized the Italian Renaissance at its zenith. He remains a towering figure, not just for Siena, but for the entire history of Western art, architecture, and engineering.