John George Brown stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century American art, a painter whose name became synonymous with sentimental yet meticulously rendered depictions of urban youth. Though born across the Atlantic, his artistic identity was forged on the streets of New York City, capturing the public imagination with images of newsboys, bootblacks, and street musicians. His work, immensely popular during his lifetime, offers a unique window into the social fabric and popular tastes of Victorian America, blending technical skill inherited from British traditions with distinctly American subject matter. Understanding Brown requires exploring his transatlantic journey, his artistic development, his engagement with the American art establishment, and the enduring, if sometimes debated, legacy of his work.

From Durham to New York: An Atlantic Crossing

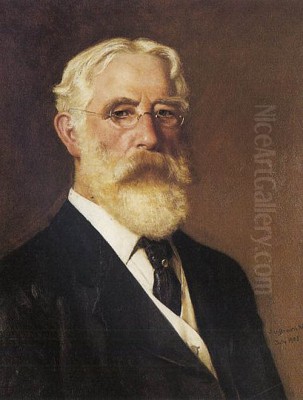

John George Brown's story begins not in the bustling metropolis he would later call home, but in the historic city of Durham, England, where he was born on November 11, 1831. His origins were modest, and his parents, perhaps concerned about the precariousness of an artistic career, initially steered him towards a more practical trade. He was apprenticed as a glass cutter and worked in the glass industry for several years, first in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and later in Edinburgh.

Despite the demands of his trade, Brown's artistic inclinations could not be suppressed. He pursued his passion through evening classes, demonstrating early dedication. In Newcastle, he studied at the School of Design under William Bell Scott, a painter and poet associated with the Pre-Raphaelite circle, known for his historical subjects and detailed style. This early exposure to meticulous draftsmanship likely left an imprint on Brown's developing technique.

His studies continued in Edinburgh at the Trustees' Academy, an institution that had nurtured earlier Scottish talents like Sir Henry Raeburn and Sir David Wilkie. Working by day and studying by night, Brown honed his skills, absorbing the academic principles of drawing and composition. However, the lure of greater opportunities, possibly combined with personal circumstances (some accounts suggest he left Britain abruptly), led him to emigrate. In 1853, at the age of twenty-two, John George Brown arrived in New York City, ready to forge a new path.

Establishing a Foothold in the American Art World

Upon arriving in America, Brown initially continued his work in the glass trade, finding employment at a factory in Brooklyn. Yet, his artistic ambitions remained paramount. He enrolled in classes at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York, studying under the miniature painter Thomas Seir Cummings. This period was crucial for adapting his skills to the American context and connecting with the burgeoning New York art scene.

A significant turning point came through his personal life. Brown married the daughter of his employer at the glass factory. This connection provided not only emotional support but potentially the financial stability needed to transition fully into an artistic career. By 1860, he felt confident enough to open his own studio in Manhattan, dedicating himself entirely to painting.

His timing coincided with a growing market for genre painting in America – scenes depicting everyday life. While landscape painters of the Hudson River School, like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, had dominated the previous generation, there was an increasing appetite for narrative works that reflected the changing face of American society, particularly its rapid urbanization. Brown was poised to tap into this demand.

The Rise of the "Bootblack Raphael"

Brown quickly found his niche, focusing on the lives of New York City's street children. His breakthrough came around 1860 with the painting His First Cigar. This work, depicting young boys experimenting with smoking, struck a chord with the public, combining youthful mischief with a hint of social observation. It garnered national attention and established Brown's reputation.

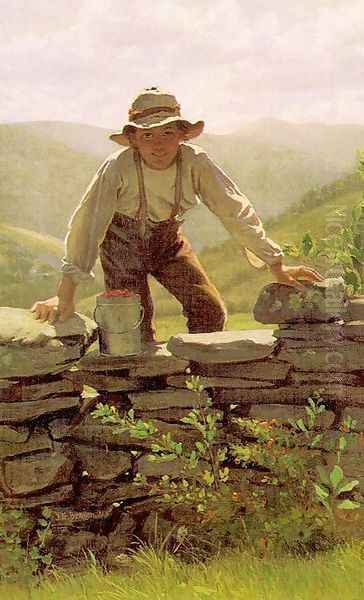

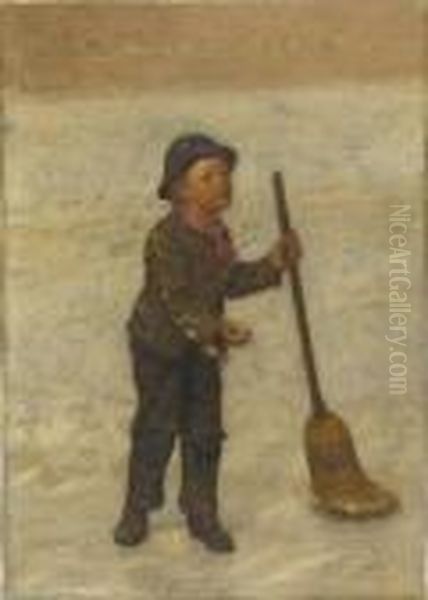

He became particularly known for his portrayals of bootblacks (shoe-shiners) and newsboys – ubiquitous figures in the nineteenth-century urban landscape. Works like The Music Lesson, Passing Show, and Street Boys at Play presented these children not as destitute victims, but often as plucky, resourceful, and charmingly ragged individuals. They were depicted cleaning shoes, selling newspapers, playing marbles, or simply pausing in a moment of camaraderie.

Brown's approach was characterized by meticulous detail. Every patch on a worn jacket, the scuff on a boot, the texture of cobblestones, was rendered with painstaking care. This precision, perhaps echoing his early training under Scott and the broader Victorian taste for detailed realism, gave his paintings an air of authenticity that appealed to viewers. His figures were clearly drawn and solidly modeled, often presented in carefully composed groupings that told a simple story.

His popularity soared. He was affectionately, if somewhat ironically, nicknamed the "Bootblack Raphael," a testament to his chosen subject matter and the perceived high quality of his execution within that genre. Collectors eagerly sought his paintings, and his work became a staple at exhibitions.

Artistic Style: Realism, Sentiment, and Criticism

John George Brown's style is best understood as a form of sentimental realism. He drew heavily on the traditions of British genre painting, exemplified by artists like Sir David Wilkie, who depicted scenes of rural life with narrative detail and emotional warmth. Brown adapted this approach to the urban American environment, focusing on subjects that evoked sympathy and admiration rather than social critique.

His commitment to realism was evident in his detailed rendering of clothing, faces, and settings. He often paid his young subjects to pose for him, aiming for accuracy in their appearance and posture. This gave his work a documentary quality, capturing the look of street life in his era. However, this realism was tempered by a pervasive sentimentality. Brown's children, despite their often ragged clothes, usually appear clean, healthy, and cheerful. The harsh realities of poverty, exploitation, and disease that afflicted many street children were largely absent from his canvases.

This idealized portrayal was a key factor in his popular success. Victorian audiences often preferred art that was morally uplifting and emotionally reassuring. Brown provided images of resilience and inherent goodness triumphing over hardship. His bootblacks might be poor, but they were depicted as honest, hardworking, and possessing a natural charm. This optimistic view resonated with the era's belief in self-reliance and the potential for upward mobility.

However, this same quality drew criticism, particularly from later generations and more discerning contemporary critics. His work was sometimes seen as overly sweet, repetitive, and lacking in genuine social commentary. Compared to European realists like Gustave Courbet or Jean-François Millet, who depicted labor and poverty with a grimmer honesty, Brown's vision seemed sanitized. His color palette was also noted as being somewhat subdued or "flat," lacking the vibrancy or atmospheric effects pursued by other contemporaries.

Representative Works: Capturing Street Life

Several paintings stand out as representative of Brown's oeuvre and his recurring themes.

His First Cigar (c. 1860): As mentioned, this was a pivotal early work. It captures a moment of youthful transgression, depicting boys experimenting with adulthood through smoking. The painting's narrative appeal and relatable theme of youthful curiosity helped launch Brown's career.

The Longshoremen's Noon (1879): While famous for children, Brown also depicted working-class adults. This painting shows dockworkers taking their midday break. It demonstrates his skill in composing multi-figure scenes and capturing the physiognomy and attire of laboring men, though still imbued with a sense of dignity and order rather than overt hardship. It resides in the collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (now part of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.).

The Music Lesson (various versions): A recurring theme involved street musicians or children learning music. These works often highlighted the perceived innate sensitivity or artistic potential found even among the poor, reinforcing the sentimental appeal of his subjects. The detailed rendering of instruments and the focused expressions of the figures are typical of his style.

Passing Show (1877): Exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon, this title suggests a scene capturing the transient moments and characters of street life. Such works often involved complex groupings and interactions, showcasing Brown's ability to orchestrate a narrative within a single frame.

Street Boys at Play (c. 1900): Exhibited at the Paris Exposition, this work exemplifies his continued focus on the theme of children finding joy and camaraderie amidst urban settings. Games like marbles were common motifs, symbolizing innocence and resourcefulness.

Button Up (or similar titles): Paintings focusing on simple, everyday actions, like a boy buttoning his coat, allowed Brown to concentrate on character study and detailed rendering of textures, highlighting the individuality of his subjects within their typical environment.

These works, and many others like them, cemented Brown's reputation. They were easily understood, emotionally engaging, and technically proficient in a way that aligned perfectly with popular Victorian taste.

Professional Life and Institutional Affiliations

Beyond his studio practice, John George Brown was an active participant in the American art establishment. He recognized the importance of professional organizations for advancing an artist's career and fostering a national artistic identity.

His association with the National Academy of Design (NAD) was central to his career. Having studied there, he was elected an Associate Member (ANA) in 1861 and achieved full Academician status (NA) in 1863. The NAD was the premier art institution in the country at the time, and membership conferred significant prestige. Brown was a regular exhibitor at the Academy's annual exhibitions, showcasing his latest works to potential patrons and the public nearly every year until 1912, the year before his death. His commitment extended to leadership roles; he served as the NAD's Vice President from 1899 to 1904. His colleagues at the Academy included prominent figures across various genres, from landscape masters like Frederic Edwin Church and Sanford Robinson Gifford to fellow genre painters.

Brown was also instrumental in the development of watercolor painting in America. He was a charter member of the American Watercolor Society (AWS), founded in 1866. Watercolor was gaining recognition as a serious medium, and the AWS played a vital role in promoting it. Brown's dedication to the medium and the society was profound; he served as its president for an extended period, from 1887 to 1904. This leadership position underscored his standing within the broader art community.

Furthermore, Brown was involved with other key organizations. He was a member of the Society of American Artists, an organization formed by younger artists seeking alternative exhibition venues to the NAD, suggesting Brown maintained connections across different factions of the art world. He was also a member of the Artists' Fund Society, dedicated to providing financial assistance to artists in need. Locally, he helped found the Brooklyn Art Association and was part of the Brooklyn Sketch Club, where he formed friendships with fellow artists like Seymour Joseph Guy, another painter known for detailed genre scenes, often featuring children.

His participation extended beyond New York. His work was exhibited nationally, including appearances at the California State Fairs in 1881 and 1884, and internationally, with showings at the Paris Salon and the Paris Exposition, indicating his ambition to reach a wider audience.

Later Career and Landscape Painting

While the charming street urchins remained his bread and butter throughout most of his career, Brown did explore other subjects, particularly in his later years. He developed an interest in landscape painting, often depicting rural scenes from upstate New York or New England.

Unlike his genre scenes, which were carefully composed and executed for the market, Brown often stated that he painted landscapes primarily for his own pleasure, as a form of relaxation. These works show a different sensibility, often focusing on the effects of light and atmosphere in nature. Stylistically, some of these landscapes show an awareness of contemporary trends. Influences from painters associated with Luminism, such as Albert Bierstadt and Worthington Whittredge, can sometimes be detected in his handling of light and serene compositions.

These landscapes, however, never achieved the fame or commercial success of his street scenes. They remained a more private aspect of his artistic practice. His public identity was firmly fixed as the painter of the New York newsboy and bootblack. He continued to produce his signature genre works well into the early 20th century, adapting slightly perhaps, but largely adhering to the formula that had brought him such renown.

Commercial Success and the Power of Reproduction

John George Brown was not only a popular artist but also a commercially astute one. He understood the market and capitalized effectively on the appeal of his work. His paintings commanded high prices from wealthy collectors, making him one of the most financially successful artists of his generation in America.

A significant factor in his widespread fame and financial success was the reproduction of his images. Brown actively managed the rights to his paintings, and many were reproduced as engravings or lithographs. These prints made his work accessible to a much broader middle-class audience who could not afford original paintings.

Famously, his images were licensed for commercial use. One notable arrangement involved the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (A&P), which distributed chromolithographs of his paintings with packages of tea and coffee. This marketing strategy brought Brown's charming bootblacks and newsboys into countless American homes, embedding his imagery deeply into the popular culture of the era. While some artists might have disdained such commercialization, Brown seemed to embrace it as a way to extend his reach and secure his financial standing.

This commercial success, however, also fueled some of the criticism leveled against him. Detractors argued that his focus on easily reproducible, sentimental subjects was driven more by profit than by artistic integrity. They suggested he was essentially mass-producing variations on a theme known to sell well, rather than pushing artistic boundaries or exploring more challenging subjects.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

To fully appreciate John George Brown's place, it's helpful to consider him alongside other artists of his time. His detailed realism connects him broadly to the Victorian aesthetic prevalent on both sides of the Atlantic. His teacher, William Bell Scott, linked him to Pre-Raphaelite circles, though Brown's subject matter differed significantly.

In America, his focus on everyday life places him within the genre painting tradition alongside figures like Eastman Johnson, known for his scenes of rural life (like maple sugaring) and post-Civil War African American life, and Winslow Homer, whose early career included illustrations and genre scenes before he moved towards more powerful depictions of nature and human struggle. While Homer and Johnson often explored deeper social or psychological themes, Brown generally maintained a lighter, more optimistic tone.

His friend Seymour Joseph Guy, also British-born, shared Brown's penchant for meticulous detail and sentimental scenes involving children, often in interior settings. Compared to the starker realism of Thomas Eakins, who focused on anatomy, science, and unflinching portraiture, Brown's work seems less intellectually rigorous but more emotionally accessible to the general public.

His later landscape work can be seen in the context of artists like Albert Bierstadt and Worthington Whittredge, key figures in the second generation of the Hudson River School and proponents of Luminism. However, Brown never dedicated himself to landscape with the same intensity as specialists like George Inness, who moved towards a more Tonalist, atmospheric style.

While Impressionism was emerging during the latter part of Brown's career, championed by American artists like Mary Cassatt and Childe Hassam, Brown remained largely untouched by its stylistic innovations. He stayed true to the detailed, narrative style that had defined his success, even as artistic tastes began to shift towards looser brushwork and a focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and color. His contemporaries also included successful academic painters like William Merritt Chase, known for his bravura brushwork and diverse subjects.

Legacy and Reassessment

John George Brown died in New York City on February 8, 1913, at the age of 81. By the time of his death, the art world was already undergoing profound changes. The Armory Show, which introduced European modernism to a shocked American audience, took place in the same year. Brown's sentimental realism, once the height of popular taste, began to look dated to modernist critics and artists.

For much of the 20th century, Brown's work was largely dismissed by the critical establishment as overly Victorian, sentimental, and commercially driven. His paintings were seen as charming relics of a bygone era rather than significant artistic statements. However, in recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in 19th-century academic and genre painting, leading to a reassessment of figures like Brown.

Today, art historians recognize his technical skill, particularly his draftsmanship and ability to render detail. His work is valued as a social document, offering insights into the urban environment of late 19th-century America and the popular ideologies of the time, even if through an idealized lens. His paintings provide a visual record of the street trades and the lives of children in the burgeoning cities.

While he may not be ranked among the great innovators of American art like Homer or Eakins, John George Brown holds a secure place as one of the most popular and successful painters of his era. His work reflects the aspirations, anxieties, and tastes of Victorian America. The enduring appeal of his images, even if viewed now with a more critical eye towards their sentimentality, speaks to his ability to connect with a fundamental human interest in stories of resilience, innocence, and everyday life. His journey from an English glass factory to the presidency of the American Watercolor Society and the status of a beloved national artist remains a compelling story of transatlantic ambition and artistic dedication. His bootblacks and newsboys continue to gaze out from his canvases, reminders of a specific moment in American history captured by an artist who understood his audience perhaps better than any other.