The 19th century in France was a period of immense artistic ferment, witnessing the twilight of Neoclassicism, the passionate drama of Romanticism, the unflinching gaze of Realism, the revolutionary optics of Impressionism, and the diverse currents of Post-Impressionism. Within this dynamic landscape, numerous artists carved out their niches, some achieving widespread fame, others contributing more quietly to the rich tapestry of the era. Charles Édouard Frère belongs to a fascinating category: an artist born into a family already distinguished in the arts, tasked with forging his own path while inevitably linked to the reputation of his kin. His story is intertwined with that of his father, Pierre-Édouard Frère, a celebrated genre painter, and his uncle, Charles-Théodore Frère, a prominent Orientalist. Understanding Charles Édouard Frère requires navigating these familial connections and placing his work within the artistic currents of his day.

The Frère Family: An Artistic Dynasty

To appreciate Charles Édouard Frère, one must first acknowledge the artistic environment into which he was born. His father, Pierre-Édouard Frère (1819–1886), was a highly successful and influential painter. Pierre-Édouard studied under the historical painter Paul Delaroche, a master of dramatic and meticulously rendered scenes. Delaroche, known for works like "The Execution of Lady Jane Grey," instilled in his pupils a strong foundation in academic technique, emphasizing drawing, composition, and narrative clarity.

However, Pierre-Édouard Frère diverged from his master's grand historical themes, finding his calling in the depiction of everyday life, particularly scenes involving children and humble domestic interiors. His work was characterized by its warmth, sentimentality, and keen observation of human nature. He became a leading figure in what was sometimes termed "sympathetic art," capturing the simple joys, sorrows, and activities of ordinary people, especially the young. His paintings, such as "The Little Glutton," "Going to School," and "Coming from School," resonated deeply with a bourgeois audience in France, England, and America.

The renowned English art critic John Ruskin was a fervent admirer of Pierre-Édouard Frère's work, praising its truthfulness, tenderness, and moral integrity. Ruskin's endorsement significantly boosted Frère's international reputation. Pierre-Édouard established a studio in Écouen, a village north of Paris, which became a hub for artists interested in genre painting, effectively forming the Écouen School. Artists like Auguste Schenck and Théophile Emmanuel Duverger were associated with this circle, drawn to the rustic charm and the focus on sentimental, anecdotal scenes. The success of Pierre-Édouard Frère created a significant legacy and, undoubtedly, a complex backdrop for his son, Charles Édouard.

Adding another dimension to the family's artistic profile was Charles-Théodore Frère (1814–1888), Pierre-Édouard's elder brother and thus Charles Édouard's uncle. Known as Théodore Frère, he was a distinguished Orientalist painter. After initial studies, Théodore Frère embarked on extensive travels, notably to Algeria in the late 1830s, and later to Egypt, Turkey, Syria, and Palestine. He even established a studio in Cairo. His canvases were filled with vibrant depictions of bustling souks, serene desert landscapes, caravans, mosques, and scenes of daily life in the Near East. Works like "View of Cairo," "Caravan at Sunset," and "Jerusalem from the Valley of Jehoshaphat" captured the European fascination with the "Orient." His style was marked by a keen attention to light, color, and ethnographic detail, placing him in the company of other great Orientalist painters such as Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, and the British artist John Frederick Lewis. Théodore Frère's work, with its exotic subject matter and often brilliant light effects, offered a stark contrast to the intimate, European genre scenes of his brother.

Charles Édouard Frère: Life and Artistic Development

Information regarding the specific birth and death dates of Charles Édouard Frère, the son of Pierre-Édouard, is less consistently documented than that of his more famous father and uncle, leading to some of the aforementioned confusion in art historical records. He was, however, active as a painter in the latter half of the 19th century. Growing up in such an artistic household, it was almost inevitable that Charles Édouard would receive his primary artistic training from his father. He would have been immersed in the principles of genre painting, the importance of careful observation, and the techniques favored by Pierre-Édouard and the Écouen School.

While details of his early life and formal training beyond his father's studio are scarce, it is clear he pursued a career as a painter. He became known as a painter of genre scenes, landscapes, and portraits, following somewhat in his father's footsteps but also seeking to establish his own voice. The influence of Pierre-Édouard is discernible in his choice of subject matter, often focusing on everyday scenes and figures. However, Charles Édouard also explored landscape painting, a genre that was undergoing significant transformation during his lifetime with the rise of the Barbizon School and, subsequently, Impressionism.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Representative Works of Charles Édouard Frère

Charles Édouard Frère's artistic output appears to have centered on genre scenes, often with a focus on rural life, children, and domestic activities, echoing his father's thematic concerns. His works aimed to capture moments of daily existence, imbued with a sense of narrative and character. Unlike his uncle Théodore's grand Orientalist vistas, Charles Édouard's canvases were generally more modest in scale and subject, focusing on the familiar rather than the exotic.

Several works are attributed to Charles Édouard Frère, providing insight into his artistic preoccupations. Titles such as "Petit Saltimbanque" (Little Tumbler/Acrobat), "Plagiare" (Plagiarist, perhaps referring to a child copying), and "Poule aux Œufs d'Or" (The Hen that Lays Golden Eggs, likely an illustration of the fable) suggest an interest in anecdotal scenes, possibly with a moral or charming narrative element, much like his father's oeuvre.

Other recorded works further illustrate his range:

"No Fire - No Burn" (1877): This oil painting, measuring 19 x 16.5 inches, suggests a domestic or genre scene, perhaps with a cautionary or humorous undertone.

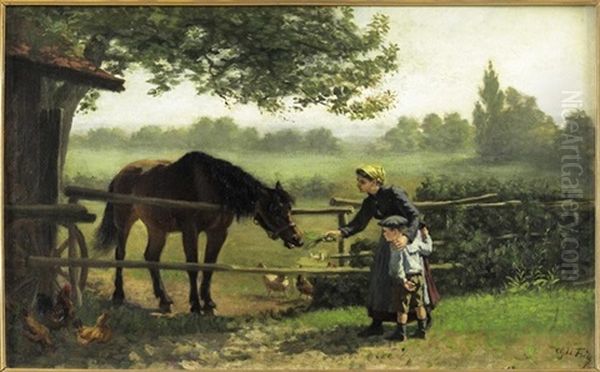

"Young Girl Feeding A Horse": This title clearly indicates a rural genre scene, a popular theme in 19th-century art that appealed to a sense of pastoral simplicity.

"The Snow" (exhibited Salon of 1876): This points to his engagement with landscape painting, and specifically the challenges and beauties of a winter scene. The depiction of snow was a subject tackled by many artists of the period, including Gustave Courbet and the Impressionists like Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley, who were fascinated by its light-reflecting qualities.

"Before the Rain" (exhibited Salon of 1875): Another landscape, this work would have focused on capturing a specific atmospheric effect, a concern shared by Barbizon painters and Impressionists alike.

"Machine à battre, à Frépillon" (Threshing Machine at Frépillon, exhibited Salon of 1878): This title is particularly interesting. Frépillon is a village near Écouen. The depiction of a threshing machine suggests an interest in modern rural life and agricultural technology, a theme also explored by Realist painters like Jean-François Millet, though Millet's focus was often more on the timeless labor of the peasant. This work was described as a portrait, which could mean a portrait of people with the machine, or the machine itself as a subject of detailed study.

"Embarcadère" (Loading Dock/Quay, exhibited Salon of 1877): This could be a scene of commerce and daily activity, perhaps by a river or canal, offering opportunities for depicting figures, goods, and a specific environment.

"A Bit of Paris" (exhibited Salon of 1877): This indicates an engagement with urban scenes, a subject that became increasingly popular with artists like Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and Gustave Caillebotte, who sought to capture the dynamism and social fabric of modern Parisian life.

These titles suggest that Charles Édouard Frère, while rooted in the genre tradition of his father, also explored landscape and scenes of contemporary life, including both rural and urban settings. His style likely maintained a degree of academic finish and narrative clarity, as was common for Salon painters of the era who were not part of the avant-garde movements.

Salon Exhibitions and the 19th Century Art World

For an artist like Charles Édouard Frère, the Paris Salon was the primary venue for exhibiting work and gaining recognition. The Salon, organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts for much of the 19th century, was a massive annual (or biennial) exhibition that attracted thousands of entries and visitors. Success at the Salon could lead to critical acclaim, state purchases, private commissions, and a solid career. Conversely, rejection by the Salon jury could be a significant setback.

Charles Édouard Frère was a regular exhibitor at the Salon. His participation in the Salons of 1875, 1876, 1877, and 1878 with the works mentioned above demonstrates his active engagement with the official art world. These exhibitions placed his work before the public and critics, alongside a vast array of other artists, from established academic masters to emerging talents.

The art world of Charles Édouard Frère's active period was incredibly diverse. The influence of Realism, championed by Gustave Courbet with his unidealized depictions of rural life and contemporary events, was still potent. The Barbizon School painters, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Charles-François Daubigny, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, had revolutionized landscape painting by emphasizing direct observation of nature and plein-air sketching, paving the way for Impressionism.

By the 1870s, when Charles Édouard was exhibiting, Impressionism was making its controversial debut. The first Impressionist exhibition was held in 1874, featuring artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and Berthe Morisot. Their focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, their use of broken color, and their often contemporary subject matter challenged academic conventions and initially met with public ridicule and critical hostility.

While Charles Édouard Frère's work, judging by the titles and his father's influence, was likely more aligned with traditional genre and landscape painting than with the radicalism of the Impressionists, he would have been acutely aware of these shifting artistic tides. His landscape subjects, such as "The Snow" and "Before the Rain," suggest an interest in atmospheric effects that was a hallmark of both Barbizon and Impressionist painting, though his treatment would likely have been more descriptive and less purely optical than that of Monet or Pissarro.

Distinguishing Charles Édouard: The Challenge of a Shared Name

A significant challenge in assessing Charles Édouard Frère's career is the persistent confusion with his uncle, Charles-Théodore Frère. The latter's distinctive Orientalist subjects and his established reputation make him a more prominent figure in art history. It is not uncommon for works by one to be misattributed to the other, or for biographical details to be conflated, especially given the shared surname and the less extensive documentation available for Charles Édouard.

Charles-Théodore Frère's Orientalism was part of a broader European fascination with the cultures of North Africa and the Middle East, fueled by colonialism, travel, and romantic literature. His paintings, often characterized by their luminous quality and detailed rendering of exotic locales, appealed to a taste for the picturesque and the unfamiliar. Artists like Eugène Fromentin, also a painter and writer, similarly captured the landscapes and life of Algeria with a blend of ethnographic interest and artistic sensibility. The work of Charles-Théodore was admired by some of the Impressionists, including Monet, reportedly for its sensitivity to light – a quality that, despite the difference in subject and technique, resonated with their own preoccupations.

Charles Édouard Frère, by contrast, seems to have remained focused on European, and particularly French, subjects. His art did not venture into the exoticism of his uncle but rather explored the familiar narratives of home, countryside, and local life. This distinction is crucial for art historians seeking to delineate the individual contributions of each family member.

Market Reception and Legacy

The art market of the 19th century was robust, particularly for works that appealed to the tastes of the burgeoning middle and upper classes. Pierre-Édouard Frère, Charles Édouard's father, achieved considerable market success, his paintings being sought after by collectors in France, Britain (thanks in part to Ruskin's advocacy), and the United States. His works were widely reproduced as engravings, further popularizing his images.

The market reception for Charles Édouard Frère's own work is less clearly documented. As the son of a famous artist, he would have had certain advantages in terms of access and name recognition. However, he also faced the challenge of being compared to his highly successful father and his distinctive uncle. His Salon participation indicates a professional career, and his works would have been available for purchase. The value of his paintings today is generally more modest than that of his father or uncle, reflecting their relative prominence in the art historical canon.

One auction record mentions a signed watercolor by a "Charles Edouard Frere" titled "The Art Critic," which sold in 2023 for a modest sum. This suggests his works do appear on the market, often in the category of 19th-century European genre painting. The broader "Frère" name often commands interest, but discerning collectors and dealers would differentiate between the works of Pierre-Édouard, Charles-Théodore, and Charles Édouard.

The legacy of Charles Édouard Frère is that of a competent and dedicated painter working within the established traditions of his time, particularly genre and landscape painting. He contributed to the artistic output of the Écouen circle and the broader Salon system. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of the Impressionists or a defining figure like his father in the realm of sentimental genre, his work provides a valuable glimpse into the artistic currents and tastes of the latter 19th century. He represents the many artists who sustained the diverse ecosystem of the art world, producing works that found an appreciative audience and contributed to the visual culture of their era. His career underscores the complexities of artistic identity within a family legacy, navigating the influences of his forebears while seeking his own path. His paintings of everyday French life, rural landscapes, and urban vignettes offer a quiet counterpoint to the more dramatic or exotic themes explored by other members of his talented family.

In conclusion, Charles Édouard Frère remains a figure deserving of clearer art historical delineation. By carefully sifting through records, attributions, and contextual information, we can better appreciate his individual contribution as a French painter of the 19th century, a participant in the Salon tradition, and an heir to a significant, if sometimes overshadowing, artistic lineage. His work reflects the enduring appeal of genre scenes and landscapes that tell a human story or capture the character of a place, themes that resonated with many artists and art lovers of his time, from the meticulous academic painters to those on the cusp of modernism, such as the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens, known for his elegant depictions of contemporary women, or even the more socially conscious works of artists like Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, who documented French peasant life with dignity and realism. Charles Édouard Frère's art finds its place within this rich and varied spectrum.