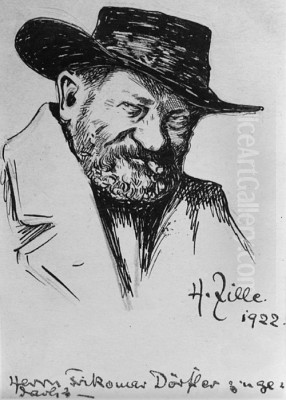

Heinrich Zille stands as one of Germany's most beloved and significant graphic artists, illustrators, and photographers from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Active primarily in Berlin, Zille dedicated his career to documenting the lives of the city's working class, the inhabitants of its sprawling tenements, backyards, and bustling streets. With a unique blend of sharp wit, profound empathy, and unflinching realism, he captured the struggles, sorrows, and small joys of ordinary Berliners, earning him the affectionate nickname "Pinselheinrich" (Brush Henry) and a lasting place in the cultural memory of the city and the nation. His work provides an invaluable window into the social fabric of Wilhelmine and Weimar era Berlin.

From Poverty to Print: Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Rudolf Heinrich Zille was born on January 10, 1858, in Radeburg, near Dresden, Saxony. His origins were humble; his father, Johann Traugott Zille, was a watchmaker and blacksmith, while his mother, Ernestine Louise (née Heinitz), came from a mining family. The family faced significant financial hardship, exacerbated by the father's debts and periods of imprisonment. Seeking better opportunities, the Zilles moved to Berlin in 1867, settling in the impoverished area near Schlesischer Bahnhof. Young Heinrich experienced the harsh realities of urban poverty firsthand, experiences that would deeply inform his later artistic vision.

His formal education was limited, but his artistic talent was evident early on. He took drawing lessons, and his teacher recognized his potential, recommending an apprenticeship. From 1872, Zille trained as a lithographer under Fritz Hecht. During this time, he also attended evening classes at the Royal School of Art in Berlin, where he studied under Professor Theodor Hosemann. Hosemann, himself known for his illustrations of Berlin life, albeit from an earlier, more Biedermeier perspective, likely influenced Zille's interest in everyday scenes and character studies.

The Craftsman Artist: Lithography and Photography

After completing his apprenticeship in 1875, Zille worked in various graphic arts companies. A significant step came in 1877 when he joined the renowned "Photographische Gesellschaft" (Photographic Society), a firm specializing in photogravure and other reproductive techniques. Here, he honed his skills not only in lithography but also gained exposure to the burgeoning field of photography, working on retouching and printing processes. This period provided him with technical mastery and a steady income, though his true passion lay in his own drawing and observation.

His professional life was briefly interrupted by compulsory military service from 1880 to 1882, serving with the Guard Grenadiers in Frankfurt an der Oder. Upon his return, Zille continued his work in the graphic arts industry. In 1883, he married Hulda Friske, the daughter of a school teacher. The couple would go on to have three children: Margarete, Hans, and Walter. Family life provided stability, but Zille continued to relentlessly sketch and draw the world around him, filling countless notebooks with observations captured during his walks through Berlin's poorer districts.

Chronicler of the "Milljöh": Finding His Subject

Zille's true artistic identity emerged as he focused intently on what he called his "Milljöh" – the specific social environment or milieu of Berlin's working-class neighborhoods. He ventured into the crowded tenements (Mietskasernen), dimly lit backyards (Hinterhöfe), smoky pubs (Kneipen), bustling marketplaces, and street corners where life unfolded in its rawest form. He depicted families crammed into small apartments, children playing amidst rubbish heaps, weary laborers, prostitutes, street vendors, and the unemployed.

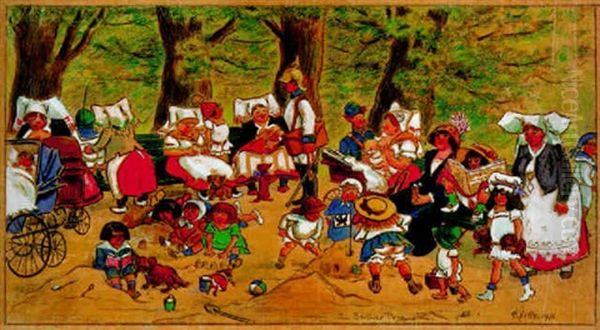

His depictions were far removed from idealized portrayals. He showed the grime, the poverty, the exhaustion, and the social ills prevalent in these areas. Yet, his work was rarely purely bleak. Zille possessed a remarkable ability to infuse his scenes with humor, resilience, and a deep sense of humanity. He captured the specific Berlin dialect (Berliner Schnauze) in his witty captions and revealed the small pleasures and coping mechanisms of people facing adversity – a shared drink, a moment of camaraderie, the boisterous energy of children at play. His art was sometimes labeled "Kunst aus der Gosse" (Art from the Gutter), a term he likely embraced as validation of its authenticity.

Style and Technique: Humor, Satire, and Realism

Zille developed a distinctive graphic style characterized by its directness and expressive line work. He primarily worked with pencil, charcoal, ink, and watercolor, often combining these media. His lithographs and etchings also form a significant part of his oeuvre. His drawing could be quick and sketchy, capturing fleeting moments, or more detailed and solid, defining characters and environments with clarity. While influenced by the observational focus of Naturalism, perhaps drawing inspiration from French artists like Honoré Daumier known for social commentary, Zille's approach was uniquely his own.

A key element was his use of humor and satire. This was not gentle amusement but often a sharp, critical tool used to expose social hypocrisy, bureaucratic absurdity, and the stark contrasts between the lives of the rich and the poor. His captions, often written in authentic Berlin dialect, were integral to the drawings, adding another layer of meaning and wit. Despite the often harsh realities depicted, Zille's underlying empathy for his subjects always shone through. He portrayed them not as mere victims, but as complex individuals possessing dignity, resilience, and a particular brand of urban vitality.

Zille the Photographer: Capturing Berlin's Fleeting Moments

Alongside his drawing and printmaking, Zille was an early and avid photographer. Starting around the 1890s, he used the camera to document the same Berlin milieu that fascinated him in his drawings. He captured candid street scenes, children playing, market life, architectural details of tenements, and even scenes from public baths and recreational outings, like those at Wannsee lake. His photographic work is considered pioneering in the realm of social documentary and street photography in Germany.

While some debate has arisen regarding the attribution of certain photographs later published under his name, there is no doubt that Zille actively used photography as part of his artistic process. His photographs often served as studies or source material for his drawings and prints, allowing him to capture authentic details and compositions. Regardless of attribution debates concerning specific images, his engagement with photography underscores his commitment to observing and recording the reality of his time, making him a forerunner to later photographers who focused on urban life and social conditions.

Recognition and the Berlin Secession

For many years, Zille pursued his personal art alongside his commercial work. A turning point came in the early 1900s. Encouraged by prominent figures in the Berlin art world, particularly Max Liebermann, the influential Impressionist painter and president of the Berlin Secession, Zille began to exhibit his work more publicly. Liebermann recognized the unique power and authenticity of Zille's drawings and championed his inclusion in the avant-garde circles.

In 1903, Zille became a member of the prestigious Berlin Secession, an association founded in 1898 by artists seeking independence from the conservative, state-sponsored art establishment. This group included leading figures of German Impressionism and Symbolism, such as Liebermann himself, Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, and the sculptor August Gaul. Zille's inclusion, despite his less conventional style and subject matter, signaled a broadening acceptance of socially engaged art. He exhibited regularly with the Secession, gaining wider recognition and critical acclaim. His work also began appearing frequently in popular satirical magazines like Simplicissimus and Jugend, bringing his art to a mass audience.

Key Works and Enduring Themes

Rather than single monumental paintings, Zille's reputation rests on his vast body of graphic work – drawings, prints, and illustrated books. Collections like Kinder der Straße (Children of the Street) and Mein Milljöh (My Milieu) encapsulate his central themes. His depictions of children are particularly poignant, showing their resilience and premature worldliness as they navigate the harsh urban environment. Scenes set in pubs, backyards, and amusement parks reveal the social life and leisure activities of the working class.

His famous drawing Am Wannsee (1913), a small watercolor and pastel piece, captures a typical scene of Berliners enjoying an outing, showcasing his skill in capturing atmosphere and character even in recreational settings. Throughout his work, recurring character types emerge – the resourceful street urchin, the weary mother, the jovial drinker, the sharp-tongued landlady – all rendered with Zille's characteristic blend of realism and affection. He documented not just poverty, but the full spectrum of life within his chosen milieu.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Zille operated within a vibrant and rapidly changing German art scene. His teacher, Theodor Hosemann, represented an older tradition of Berlin genre illustration. His mentor, Max Liebermann, along with Corinth and Slevogt, were key figures in German Impressionism, adapting French styles to German subjects. Zille shared a deep friendship and mutual respect with Käthe Kollwitz, another powerful graphic artist deeply committed to depicting the plight of the poor and oppressed, though her style was generally more tragic and less humorous than Zille's.

While associated with the Secession, Zille's style remained distinct from both Impressionism and the emerging Expressionist movement, exemplified by groups like Die Brücke (The Bridge) with artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel, who also depicted Berlin city life but with greater emotional intensity and formal distortion. Zille can be seen alongside earlier realists like Adolph Menzel, who meticulously documented 19th-century Berlin life. His sharp social commentary also anticipates the later, more politically biting satire of Weimar artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix. Zille carved a unique niche, blending observation, social critique, and popular appeal.

Social Commentary and Political Undertones

While Zille was not an overt political activist or party member in the traditional sense (though his membership in the progressive Berlin Secession indicated his leanings), his entire body of work constitutes a powerful form of social commentary. By consistently focusing his lens on the lives of the marginalized and underprivileged, he implicitly criticized the social inequalities and governmental neglect prevalent in rapidly industrializing Berlin under the Kaiser and later during the turbulent Weimar Republic.

His humor often served to highlight the absurdity and injustice of the situations his characters faced. He exposed the gap between official morality and the realities of survival, the struggles against poverty, poor housing, and inadequate healthcare. His sympathy clearly lay with the common people, whose resilience and wit he celebrated even while documenting their hardships. His art gave voice to those often overlooked by mainstream society and high culture, making him a profoundly democratic artist.

Later Life, Honors, and Lasting Legacy

Zille's popularity grew steadily throughout his life. He became a beloved Berlin institution. His work was widely published and collected. In 1924, he was appointed a professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts, and in 1925, he was made an honorary member – a significant official recognition of his artistic contributions, strongly supported by Liebermann. This marked a remarkable journey from impoverished beginnings to acceptance by the art establishment, largely on his own terms.

Heinrich Zille died in Berlin on August 9, 1929, at the age of 71. His death was mourned throughout the city. While his reputation perhaps dipped slightly in the immediate aftermath, particularly during the Nazi era when his focus on the "common man" might have been viewed ambivalently, his work was rediscovered and celebrated anew in the post-war period, both in East and West Germany.

Today, Zille's legacy is secure. The Zille Museum in Berlin's Nikolaiviertel is dedicated to his life and work. Numerous streets and squares, as well as a park in Berlin, bear his name. His drawings and photographs remain essential documents for understanding the social history of Berlin at the turn of the 20th century. More importantly, his art continues to resonate due to its timeless depiction of human struggle, resilience, and the enduring power of humor and empathy in the face of adversity. He remains Berlin's cherished "Pinselheinrich," the artist who captured the soul of its working-class milieu like no other.

Conclusion: The People's Artist

Heinrich Zille occupies a unique and enduring position in German art history. As a draftsman, printmaker, and photographer, he dedicated his life to observing and portraying the everyday reality of Berlin's working class. His "Milljöh" was not just a subject but the very heart of his artistic universe. Combining unflinching realism with sharp wit and deep empathy, he created a body of work that is both a vital historical document and a timeless commentary on the human condition. From the backstreets of Berlin to the halls of the Academy, Zille's journey was remarkable, but his focus never wavered from the ordinary people whose lives he illuminated with such skill and compassion. He remains, truly, an artist of the people.