Introduction: An Artist of Two Hemispheres

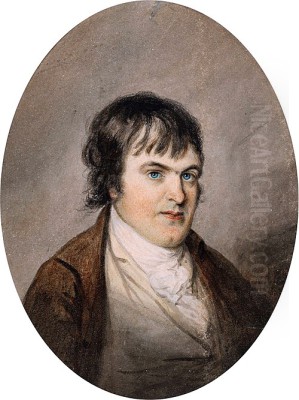

John Glover (1767-1849) stands as a significant figure in the history of landscape painting, uniquely bridging the artistic worlds of Georgian England and colonial Australia. Born in the heart of the English countryside, he rose to prominence as a master watercolourist and oil painter, celebrated for his picturesque views and technical skill. Later in life, he embarked on a transformative journey to Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania), where he became one of the first professional European artists to capture the distinct light, flora, and atmosphere of the Australian continent. His legacy is twofold: a respected contributor to the British landscape tradition and the foundational artist often hailed as the "father of Australian landscape painting."

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in England

John Glover was born on February 18, 1767, in Houghton-on-the-Hill, a village in Leicestershire, England. His family background was modest; his parents were farmers, and his early years involved agricultural labour. Despite this rural upbringing, or perhaps inspired by the surrounding landscapes, Glover displayed a natural inclination towards drawing from a young age. Formal art training was not immediately accessible, but his talent did not go unnoticed.

By the age of 19, around 1786, Glover secured a position as a writing master at the Free School in Appleby, then in Westmorland (now Cumbria). This role provided stability and likely allowed him some time to pursue his artistic interests. His skills developed, and his ambition grew beyond the confines of a schoolmaster's life. He began to focus seriously on landscape painting, initially favouring the medium of watercolour, which was gaining popularity and status in Britain at the time, thanks to pioneers like Paul Sandby.

A pivotal moment came in 1794 when Glover moved to the cathedral city of Lichfield in Staffordshire. Here, he established himself as a drawing and painting master, offering instruction to the local gentry and middle classes. This move marked his transition towards a full-time artistic career. Lichfield provided a supportive environment, and Glover's reputation as both a teacher and a landscape artist began to flourish. He travelled through picturesque regions of Britain, including Wales, Derbyshire, and the Lake District, sketching and gathering material for his compositions.

Ascendancy in the London Art World

While based initially in Lichfield, Glover's ambitions were increasingly directed towards London, the epicentre of the British art world. He began exhibiting his works, primarily watercolours, at the Royal Academy of Arts from 1795 onwards. His detailed, often idyllic, depictions of British scenery found favour with critics and collectors. His technique was admired for its delicacy, its handling of light, and its intricate rendering of foliage.

Glover's mastery of watercolour was central to his rising fame. He became a key figure in the professionalization of the medium. In 1804, he was a founding member of the Society of Painters in Water Colours (often referred to as the Old Water-Colour Society or OWS). This society aimed to elevate the status of watercolour painting, distinguishing it from mere preparatory sketching and asserting its validity as a medium for finished exhibition pieces, challenging the dominance of oil painting at the Royal Academy.

His standing within the OWS grew rapidly. He was elected its President in 1807 and served in that capacity again in later years. His exhibitions with the society were highly successful, and his works commanded impressive prices, sometimes exceeding those of his contemporaries. During this period, he also increasingly worked in oils, seeking the prestige associated with the medium and the potential for larger-scale, more impactful compositions suitable for Royal Academy exhibitions. His oil paintings often retained the luminous quality and detailed observation characteristic of his watercolours.

The "English Claude"

During his peak years in England, Glover earned the flattering moniker "the English Claude." This comparison likened him to the revered 17th-century French Baroque painter Claude Lorrain, whose idealized landscapes, bathed in golden light and featuring classical or pastoral themes, were highly esteemed by British collectors and artists. Glover admired Claude's work, studying his compositional structures and atmospheric effects.

Glover's own landscapes from this period often incorporated Claudian elements: carefully balanced compositions, serene atmospheres, picturesque framing devices like prominent trees, and a skillful manipulation of light to create depth and mood. He depicted the rolling hills, tranquil lakes, and historic estates of Britain with a romantic sensibility, sometimes infusing them with a gentle, Arcadian quality reminiscent of Claude. However, Glover's work was also grounded in the specific observation of nature, influenced by the burgeoning naturalism in British landscape art seen in the works of artists like Thomas Girtin, a brilliant contemporary watercolourist whose early death was much lamented.

Despite the comparison to Claude, Glover developed his own distinctive techniques. He was known for his meticulous rendering of foliage, sometimes using a "split brush" technique to create fine, feathery textures for leaves and grass. His palette, while capable of capturing the soft light of Britain, was often rich and varied. His success was undeniable, yet he faced competition from other landscape giants of the era, most notably J.M.W. Turner, whose dramatic and increasingly abstract visions of nature offered a powerful alternative. The rivalry was keenly felt, with contemporary painter John Constable reportedly expressing disdain for the public's occasional preference for Glover's more detailed style over Turner's sublime power. Other notable contemporaries in the landscape field included Richard Parkes Bonington, David Cox, and Peter De Wint, all contributing to a vibrant period for British art.

A New Horizon: Emigration to Van Diemen's Land

In his early sixties, already a highly successful and established artist in Britain, John Glover made the remarkable decision to emigrate. In 1831, accompanied by his wife and family, he set sail for Van Diemen's Land, the British penal colony that would later become the Australian state of Tasmania. The reasons for this move, undertaken at an age when many might contemplate retirement, are multifaceted. Financial considerations, including losses incurred through speculation, likely played a part. The prospect of securing land grants for his sons and establishing a pastoral estate in a new colony was also appealing. Furthermore, the allure of a completely different landscape, bathed in unfamiliar light and possessing unique flora and fauna, may have presented an irresistible artistic challenge.

Glover arrived in Hobart Town in April 1831, becoming arguably the first professional artist of significant European reputation to settle permanently in Australia. He acquired a substantial grant of land in the Nile River valley near Ben Lomond, in the north of the island. He named his property "Patterdale," after a village in the English Lake District he admired. Here, he built a house and established himself not only as an artist but also as a pastoralist, raising sheep and cattle.

This move marked a profound shift in his life and art. He was no longer just depicting landscapes; he was living within one, actively shaping it through farming while simultaneously observing and recording its features. His Tasmanian home and its surroundings would become the primary subject of his art for the remainder of his life.

Life as an Artist-Pastoralist

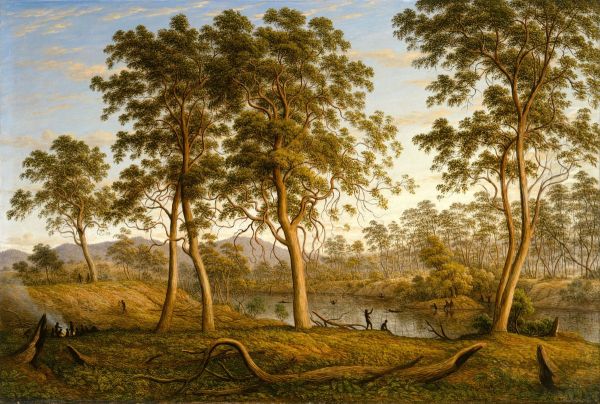

Glover's life at Patterdale provided him with constant immersion in the Tasmanian environment. His days involved overseeing the farm, but his artistic drive remained undiminished. He built a small gallery at his home to display his work. The landscape around him was vastly different from the gentle greens of England or the rugged mountains of Wales. He was confronted with the unique forms of eucalyptus trees, the sharp, clear light of the Southern Hemisphere, and the dramatic geological formations like the nearby Ben Lomond massif.

He adapted his techniques to capture this new world. While his compositional structures sometimes retained echoes of his earlier Claudian style, his focus shifted towards a more direct, naturalistic representation of the specific qualities of the Tasmanian landscape. He sketched extensively outdoors (plein-air sketching), capturing the effects of light and shadow on the distinctive vegetation and terrain. His "split brush" technique proved particularly effective for rendering the textures of eucalyptus bark and foliage under the bright Australian sun.

His paintings from this period often depict his own property and the surrounding region. Works like My Harvest Home (1835) show his house and farm activities integrated into the landscape, celebrating his new life as a landowner. Patterdale Farm (c. 1833-35) provides a detailed view of his estate, showcasing both the cultivated land and the wilder bush beyond. Mount Wellington and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point (1834) captures the topography and atmosphere of the colonial capital and its imposing natural backdrop.

Capturing the Antipodean Light and Landscape

The most significant development in Glover's Australian work was his response to the unique quality of light and atmosphere. He noted the clarity of the air and the intensity of the sunlight, which differed markedly from the softer, more diffused light of Britain. His palette adapted, incorporating brighter blues for the skies and distinctive olive greens, ochres, and greys to represent the colours of the Australian bush.

He became fascinated by the eucalyptus trees, which dominated the landscape. Unlike the familiar oaks and elms of England, these trees had sparse canopies, peeling bark, and twisting limbs. Glover meticulously studied their forms, capturing their specific character in numerous paintings and drawings. He depicted them not just as landscape elements but almost as portraits, highlighting their resilience and unique aesthetic. His ability to render the hazy, atmospheric effects caused by distance or bushfires also added a layer of authenticity to his Tasmanian views.

This dedication to capturing the specific character of the Australian environment marks Glover's crucial contribution. While earlier artists had visited and sketched parts of Australia, Glover was the first established painter to live there long-term and dedicate his mature artistic practice to interpreting its landscape. He moved beyond simply applying European conventions and sought to find an artistic language appropriate to this new world, laying the groundwork for future generations of Australian artists.

Depictions of Aboriginal Tasmanians

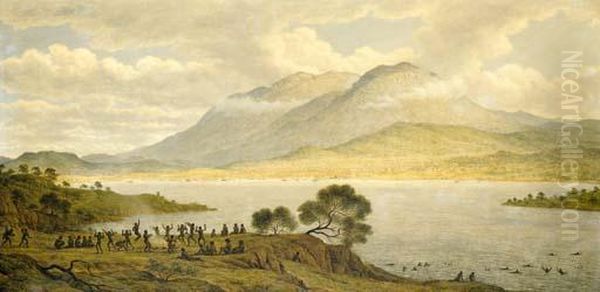

John Glover's time in Van Diemen's Land coincided with the tragic final years of the Black War, a period of intense conflict between British settlers and the Aboriginal Tasmanians (Palawa). Settler expansion had led to dispossession, violence, and the devastating decline of the Indigenous population through introduced diseases and frontier conflict. By the time Glover arrived, the government policy of forcibly removing Aboriginal people from the mainland to offshore islands, primarily Flinders Island, was underway.

Glover's paintings are among the few contemporary European artworks that depict Aboriginal Tasmanians in their ancestral land, albeit often in idealized or pastoral settings. Works such as Natives on the Ouse River (1838) and The Bath of Diana, Van Diemen's Land (1837) show Aboriginal figures hunting, fishing, or resting in harmonious-looking landscapes. These depictions are significant for recording the presence of Aboriginal people at a time of immense upheaval and loss.

However, these images are complex and have been subject to interpretation. Some critics see them as sympathetic portrayals, reflecting Glover's interest in the Indigenous inhabitants and perhaps a sense of melancholy about their fate. Others view them through the lens of the "noble savage" trope, romanticizing Aboriginal life and potentially downplaying the harsh realities of the colonial frontier. His paintings rarely depict conflict or the negative impacts of colonization directly. Regardless of interpretation, these works remain important historical documents, offering a rare visual glimpse, filtered through a European artistic sensibility, of Palawa life in the landscape before their traditional ways were irrevocably disrupted.

Exhibitions and Reception of Tasmanian Works

Despite his geographical isolation in Tasmania, Glover maintained connections with the London art world. In 1835, he sent a large consignment of sixty-eight paintings, depicting his new life and the Tasmanian landscape, back to London for exhibition. This exhibition, held at 106 New Bond Street, was a significant event, offering the British public a comprehensive view of Van Diemen's Land through the eyes of a well-known artist.

The reception was generally positive, though perhaps tinged with curiosity about the exotic subject matter. Critics acknowledged his continued technical skill but noted the difference in landscape character compared to his British works. These paintings helped shape European perceptions of Australia, presenting it not just as a remote penal colony but as a land of unique natural beauty, albeit one being transformed by settlement. The exhibition solidified Glover's reputation as the pre-eminent painter of Van Diemen's Land.

His Tasmanian works continued to be sought after, though his direct participation in the London scene inevitably lessened with distance. He remained a respected figure, a successful artist who had boldly transplanted his career to the other side of the world.

Influence and Australian Contemporaries

As the first major European landscape painter to settle in Australia, John Glover's influence was foundational, though perhaps not immediate or direct in terms of forming a distinct "school." His commitment to depicting the local environment set a precedent. Artists who followed, even if they developed different styles, operated in a context where representing the Australian landscape had been validated by Glover's example.

Conrad Martens, another significant colonial artist, arrived in Sydney slightly later (1835) and also focused on landscape, though often with a more topographical or romantic-picturesque approach influenced by his time sketching with Charles Darwin on the Beagle voyage. While Martens worked primarily in New South Wales, both he and Glover contributed substantially to the early visual record of colonial Australia.

Later prominent landscape painters in Australia, such as the Austrian-born Eugene von Guérard, who arrived in the 1850s, brought a different, more detailed and scientific approach influenced by the Düsseldorf school. Swiss-born Louis Buvelot, arriving in the 1860s, emphasized plein-air painting and a more naturalistic, less idealized view of the bush, significantly influencing the later Heidelberg School artists like Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts. While these later artists developed distinctively Australian approaches, Glover's pioneering work provided an essential starting point in the journey of Australian landscape painting.

Later Years, Legacy, and Collections

John Glover continued to paint actively at Patterdale into his later years, documenting the landscape he had come to know intimately. He remained engaged with his farm and the local community. He died at Patterdale on December 9, 1849, at the age of 82, and was buried in the graveyard at Nile Chapel, near his home.

His legacy is firmly established in both British and Australian art history. In Britain, he is remembered as a leading watercolourist of his generation and a successful landscape painter in the picturesque tradition. In Australia, his status is even more significant. The title "father of Australian landscape painting" reflects his role in establishing a tradition of professional landscape art in the colony and his dedicated effort to capture the unique essence of the Australian environment.

His works are held in major public collections across the world. In the UK, institutions like the Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and Leicester Museum & Art Gallery hold significant examples. In Australia, his paintings are key highlights in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Art Gallery of South Australia, the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG), and the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (QVMAG) in Launceston, Tasmania.

The enduring interest in Glover's work is also reflected in the art market. In recent decades, his paintings, particularly those from his Tasmanian period, have achieved high prices at auction. For instance, Ben Lomond from Mr Talbot’s Property Four Men Catching Opossums near Connorville (c. 1838) and Mount Wellington and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point (1834) have fetched multi-million dollar sums, underscoring their artistic and historical importance. Furthermore, his legacy is actively celebrated in Tasmania through the prestigious annual Glover Prize, awarded for contemporary landscape painting, keeping his name synonymous with the depiction of the Tasmanian landscape.

Conclusion: A Painter of Place

John Glover's artistic journey is a compelling narrative of adaptation and vision. From the established picturesque traditions of England to the raw, unfamiliar beauty of colonial Tasmania, he consistently sought to capture the essence of the landscapes he inhabited. His technical mastery, honed over decades, allowed him to translate the distinct light, colours, and forms of two vastly different environments onto canvas and paper. While his English work secured his reputation within the mainstream of British art, it was his bold move to Australia and his subsequent dedication to depicting its unique character that cemented his lasting historical significance. He not only documented a new world but helped Australians, both then and now, to see the beauty and distinctiveness of their own environment through art. John Glover remains a pivotal figure, an artist whose life and work eloquently speak of the power of place in shaping artistic vision.