George French Angas (1822-1886) stands as a significant figure in the annals of 19th-century art, exploration, and natural history. Born into a prominent family in England, Angas carved a unique path that took him across oceans to the newly established colonies of Australia and New Zealand, as well as to the diverse landscapes of South Africa. His multifaceted career saw him excel as a watercolourist and lithographer, a keen-eyed explorer, a dedicated natural historian, and an influential ethnographer, whose works provide invaluable, albeit complex, visual records of the lands and peoples he encountered during a period of profound global transformation.

Angas's legacy is primarily cemented by his detailed and often vibrant illustrations, which captured landscapes, flora, fauna, and, most notably, the lives and customs of Indigenous peoples at a critical juncture of colonial contact. His major published works, including South Australia Illustrated, The New Zealanders Illustrated, and The Kafirs Illustrated, became important sources of information and imagery for audiences in Britain and beyond, shaping perceptions of these distant lands. While celebrated for their artistic merit and documentary value, his works are also viewed through a contemporary lens that acknowledges the inherent perspectives and biases of the colonial era in which he operated.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

George French Angas was born in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, on April 25, 1822. He was the eldest son of George Fife Angas, a key figure in the establishment and financing of the colony of South Australia, and Rosetta French Angas. Despite his father's prominence in business and colonial affairs, and initial intentions for George French to follow a commercial path, the young Angas harboured strong artistic ambitions from an early age. This divergence from the expected trajectory led to some initial paternal disapproval.

Undeterred, Angas pursued his passion for art. He received formal training, studying anatomical drawing and lithography. A significant influence during his formative years was his tutelage under Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, a noted natural history artist and sculptor, perhaps best known today for his dinosaur models at Crystal Palace. This training undoubtedly honed Angas's skills in detailed observation and accurate rendering, qualities that would become hallmarks of his later work, particularly in his depictions of natural history subjects and ethnographic details.

His desire for travel and artistic exploration manifested early. In 1841, Angas embarked on a journey through the Mediterranean, visiting Malta and Sicily. This experience resulted in his first published work, A Ramble in Malta and Sicily (1842), illustrated with his own sketches. This early venture foreshadowed the extensive travels and illustrated publications that would define his career, combining his artistic talents with a burgeoning interest in documenting different cultures and environments.

The Australian Venture: Documenting a New Colony

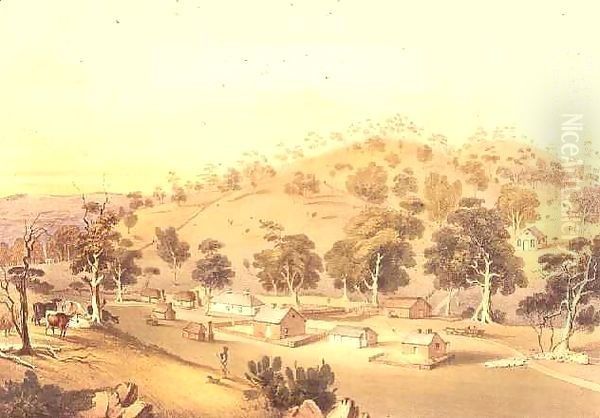

In 1843, leveraging his family connections, George French Angas sailed to South Australia, arriving in Adelaide in January 1844. His father's significant role in the colony provided him access to influential circles. During his nearly two-year stay, Angas immersed himself in exploring the relatively young British settlement and its surrounding regions. He undertook several expeditions, often travelling extensively through areas such as the Barossa Valley, the Fleurieu Peninsula, the Murray River regions, and Kangaroo Island.

A key aspect of his time in South Australia was his association with the colony's Governor, George Grey. Angas accompanied Grey on several journeys into the interior, providing him with unique opportunities to observe and sketch the landscape, the burgeoning colonial infrastructure, and, crucially, the Aboriginal inhabitants of the region. His mission, partly self-assigned and partly encouraged by the colonial administration, was to create a comprehensive visual record of the colony in its formative years.

Angas dedicated significant effort to documenting the lives of the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains, the Ngarrindjeri of the Lower Murray and Coorong, and other Aboriginal groups he encountered. He sketched portraits, scenes of daily life, ceremonial practices, hunting methods, dwellings, and artifacts. His intent, common among ethnographers of the period, was to capture these cultures before they were irrevocably altered by European settlement, viewing them through a lens that often emphasized their perceived 'primitiveness' or 'authenticity'.

South Australia Illustrated: A Visual Chronicle

The culmination of Angas's efforts in South Australia was the publication of South Australia Illustrated in London in 1847. This lavish folio volume contained sixty hand-coloured lithographs based on his original watercolours and drawings, accompanied by descriptive text. The plates showcased a wide array of subjects: panoramic views of Adelaide and its surroundings, depictions of settler life and industry, detailed botanical illustrations, and numerous studies of Aboriginal people and their cultural practices.

The work was significant not only for its artistic quality but also for its contribution to the visual representation of the colony for audiences back in Britain. It provided potential emigrants, investors, and the curious public with vivid images of this distant part of the Empire. The ethnographic plates, while filtered through Angas's European perspective, remain vital historical documents, offering some of the earliest and most detailed visual records of the material culture and appearance of South Australian Aboriginal groups during the initial decades of colonization.

Angas's watercolours from this period, many of which served as the basis for the lithographs, are particularly prized for their immediacy and detail. They demonstrate his skill in capturing likenesses, rendering textures of clothing and objects, and conveying a sense of place. Works like 'The Encampment of Native Women, near Cape Jervis' provide glimpses into the social organization and daily routines of the people he observed, preserving details that might otherwise have been lost.

Journey to New Zealand: Encountering Māori Culture

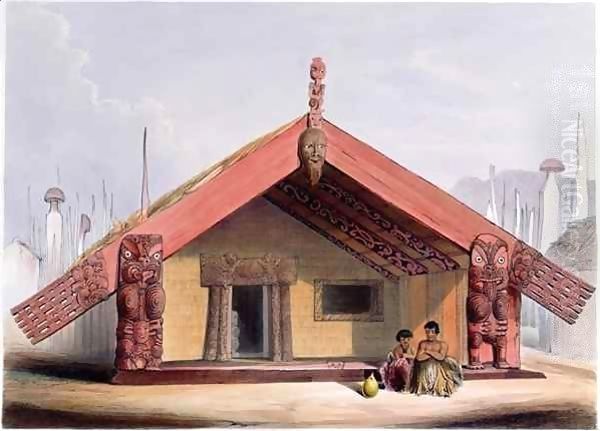

Seeking new subjects and experiences, Angas departed Australia for New Zealand in mid-1844. He spent several months travelling through various parts of the North Island, including Wellington, Porirua, Taupo, and the Waikato region. As in Australia, his primary focus was on documenting the landscapes and, particularly, the Indigenous Māori people. New Zealand offered a different cultural context, with Māori society having already experienced decades of interaction with Europeans, yet retaining strong political and cultural structures.

During his travels, Angas sought out and sketched numerous Māori individuals, including prominent chiefs (rangatira). He is known to have encountered figures such as Te Rauparaha and Te Wherowhero (later the first Māori King, Pōtatau Te Wherowhero). His portrait of Hemi Pōmare, a young Māori man who had travelled to England, is another notable work from this period. Angas often travelled with or sought introductions from colonial officials and settlers, such as Edward Jerningham Wakefield, whose own writings provide parallel accounts of the period.

His interactions allowed him to observe and sketch various aspects of Māori life: intricately carved meeting houses (wharenui), fortified villages (pā), impressive war canoes (waka taua), traditional clothing (such as flax cloaks or piupiu), tools, weapons, and ceremonial gatherings (hui). He paid particular attention to the art of Māori tattooing (tā moko), recording different facial patterns with considerable detail. These encounters provided the raw material for his next major publication.

The New Zealanders Illustrated: Depicting Māori Life

Following his return to England, Angas published The New Zealanders Illustrated in 1847, mirroring the format of his South Australian volume. This folio featured sixty hand-coloured lithographs based on his New Zealand sketches, again accompanied by his descriptive text. The work aimed to provide a comprehensive visual survey of Māori culture and the New Zealand landscape for a British audience eager for information about the colony.

The plates in The New Zealanders Illustrated are renowned for their detail and vibrancy. Angas captured the dramatic landscapes, from volcanic regions to coastal scenes. His portraits of Māori individuals, often named, convey a sense of dignity and presence, though sometimes romanticized according to European conventions of the 'noble savage'. The depictions of material culture, architecture, and social scenes offer invaluable insights into Māori society during the 1840s, a period of significant change and negotiation with the growing British presence following the Treaty of Waitangi (1840).

The production of the lithographs for this volume involved collaboration. While Angas provided the original watercolours and drawings, the skilled work of transferring these images onto stone for printing was often undertaken by professional lithographers in London, most notably J.W. Giles, who worked on many of the plates. This collaboration was standard practice for such high-quality illustrated books. The New Zealanders Illustrated cemented Angas's reputation as a leading artist-explorer documenting the peoples of the Pacific.

South African Sojourn: Documenting Diverse Cultures

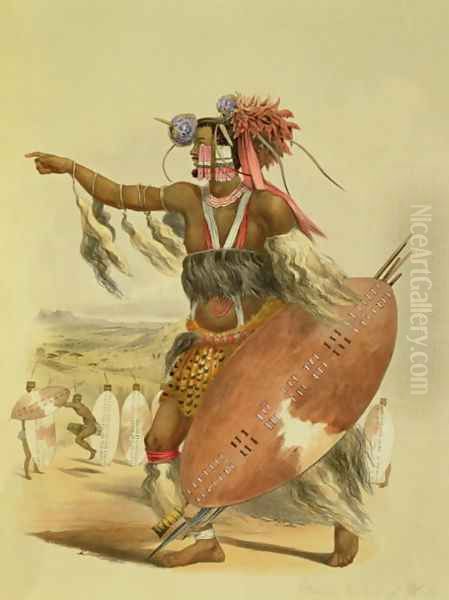

Angas's thirst for exploration was not yet quenched. Around 1846-1847, he travelled to South Africa. Here, he spent considerable time in the Cape Colony and Natal, venturing into regions inhabited by various Indigenous groups. His focus, consistent with his previous expeditions, was on documenting the traditional lifestyles, customs, appearance, and material culture of these communities, particularly the amaZulu, amaXhosa, and amaPondo peoples, whom Europeans often collectively, and often pejoratively, termed 'Kafirs'.

He sketched portraits of chiefs and commoners, scenes of village life, cattle herding (central to many local economies and cultures), dances, and traditional attire, including intricate beadwork and skin cloaks. He documented weaponry, musical instruments, and housing styles. As with his Australasian work, Angas aimed to capture these cultures before they underwent further transformation due to colonial expansion and missionary influence, which were rapidly advancing in Southern Africa during this period.

This journey resulted in his third major illustrated folio, The Kafirs Illustrated in a series of drawings taken among the Amazulu, Amaponda, and Amakosa Tribes (1849). Similar in format to his previous works, it featured hand-coloured lithographs based on his field sketches, accompanied by ethnographic descriptions. This publication provided British audiences with vivid, if sometimes stereotyped, images of the diverse peoples of Southern Africa, contributing to the growing body of colonial knowledge about the continent. It remains an important visual resource for studying the history and culture of these groups in the mid-19th century.

Narrative Accounts and Other Publications

Alongside his major illustrated folios, Angas also published narrative accounts of his travels. Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand (1847) provided a more personal and textual description of his experiences during his Australasian journeys, complementing the visual information presented in the illustrated volumes. This two-volume work offered anecdotes, observations on colonial society, descriptions of landscapes, and further ethnographic details, all presented in a style accessible to the general reader.

Throughout his career, Angas also contributed to scientific knowledge, particularly in the field of natural history. He published several papers describing new species, especially shells (conchology), based on specimens he collected during his travels. His work earned him recognition in scientific circles, and he was elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society and the Royal Geographical Society. His interest in natural history was not merely secondary; it was deeply intertwined with his artistic practice, reflecting the close relationship between art and science in the 19th century, particularly in the documentation of the natural world.

His publications collectively established him as an authority, albeit one shaped by his time, on the regions he visited. They were widely consulted and influenced perceptions of Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa for decades. The combination of detailed illustrations and engaging narrative proved highly effective in communicating the 'exotic' nature of these lands and peoples to a metropolitan audience.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Influences

George French Angas's primary medium was watercolour, which he handled with considerable skill and sensitivity. His field sketches, often executed rapidly in pencil or watercolour, formed the basis for more finished studio pieces and the subsequent lithographs. His watercolours are characterized by clear lines, careful attention to detail, and often vibrant colour palettes, used effectively to capture the quality of light and atmosphere in different environments, from the bright sunshine of Australia to the lush greens of New Zealand.

His style represents a confluence of several trends. The influence of his natural history training under Waterhouse Hawkins is evident in the precision and accuracy of his depictions of flora, fauna, and ethnographic artifacts. There is a strong element of documentary realism, aiming to record subjects faithfully. However, his work is also deeply imbued with the aesthetic sensibilities of the Picturesque and Romantic movements prevalent in 19th-century British art. Landscapes are often composed for scenic effect, and portraits, while capturing individual likenesses, sometimes conform to idealized or romanticized notions of Indigenous peoples.

Compared to other artists working in Australia and New Zealand during the same period, Angas stands out for his strong ethnographic focus. While artists like Conrad Martens or Eugene von Guérard excelled in capturing the sublime grandeur of the landscape, and Augustus Earle produced significant portraits and genre scenes earlier, Angas's major contribution lies in his systematic attempt to document Indigenous cultures through comprehensive illustrated volumes. His work offers a different perspective, more closely aligned with exploration and ethnography than purely fine art landscape painting.

Ethnographic Contributions and the Colonial Context

Angas's work occupies a significant place in the history of ethnographic representation. His illustrations provide invaluable visual data on the material culture, social practices, and physical appearance of Indigenous peoples in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa at a specific historical moment. Details of clothing, adornment (like Māori moko or Aboriginal body paint), tools, weapons, dwellings, and ceremonial objects are often rendered with meticulous care, offering insights that textual accounts alone cannot provide. He sometimes recorded Indigenous words and names, adding another layer of documentary value.

However, it is crucial to analyze Angas's work within its colonial context. While he often expressed sympathy and admiration for the peoples he depicted, his perspective was inevitably shaped by the prevailing European attitudes of his time. His work participated in the broader colonial project of observing, classifying, and documenting Indigenous populations, often framing them within evolutionary hierarchies or through romanticized tropes like the 'noble savage' or the 'vanishing race'. His emphasis on 'traditional' culture often ignored the resilience, adaptation, and ongoing histories of the peoples he encountered.

His publications, intended for a European audience, contributed to constructing particular images of these cultures – sometimes emphasizing their perceived exoticism or 'savagery', other times highlighting aspects deemed 'picturesque' or 'noble'. This complex interplay of documentation, artistic convention, and colonial ideology makes Angas's ethnographic work both a valuable resource and a subject for critical interpretation. His depictions contrast with the later, often more self-determined, representations by Indigenous artists themselves, such as the Victorian Aboriginal artist William Barak.

Pursuits in Natural History: The Conchologist

Beyond his ethnographic art, George French Angas made notable contributions to natural history, particularly in the field of conchology (the study of shells). His travels provided ample opportunities to collect specimens of marine and terrestrial molluscs, many of which were new to European science at the time. He possessed a keen eye for detail and a systematic approach, consistent with the practices of Victorian naturalists.

He described numerous new species of shells from Australia, New Zealand, and other parts of the Pacific. His findings were published in scientific journals, including the prestigious Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. His work in this area earned him considerable respect among fellow naturalists, and he is sometimes referred to as one of the foundational figures of Australian conchology. Several species of shells were named in his honour by other scientists, acknowledging his contributions to the field.

His passion for natural history continued throughout his life. Even at the age of 62, in 1884, he undertook a challenging expedition to the island of Dominica in the Caribbean. Despite his age and declining health, he spent several months collecting specimens, particularly butterflies, moths, birds, and, of course, shells. This late-life adventure underscores his enduring commitment to exploring and documenting the natural world, a pursuit that complemented and informed his artistic endeavours. This dedication mirrored the spirit of scientific inquiry prevalent among contemporaries like Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace.

Angas and His Contemporaries: Connections and Comparisons

Angas operated within a network of colonial administrators, fellow explorers, artists, and scientists. His relationship with Governor George Grey in South Australia provided crucial access and support. His collaboration with the lithographer J.W. Giles was essential for the dissemination of his work through high-quality prints. His father, George Fife Angas, remained an influential background figure, connecting him to the colonial enterprise.

In the artistic sphere, Angas can be compared and contrasted with several contemporaries. In Australia, his work differs in focus from the landscape traditions of John Glover or Eugene von Guérard, or the historical narratives of William Strutt. His ethnographic emphasis aligns more closely, perhaps, with earlier artists like Augustus Earle, though Angas's output was more systematic and published in a grander format. In New Zealand, his work complements that of other artists and surveyors like Charles Heaphy, who also documented the land and its people.

His natural history illustrations connect him to a different circle, including renowned figures like John Gould, the celebrated ornithological artist whose work also covered Australia, and Joseph Wolf, a leading animal painter in London. Angas's travels and publications also place him alongside other notable artist-explorers of the era, such as Thomas Baines, who documented parts of Africa and Australia with a similar combination of artistic skill and observational detail. His meeting with Queen Victoria, for whom he reportedly painted a portrait, indicates his aspiration for recognition within the highest circles of British society.

Later Life, Legacy, and Critical Reception

After his major expeditions and publications in the 1840s, Angas's life continued to involve travel and engagement with the colonies. He served as Secretary of the Australian Museum in Sydney from 1853 until 1860, a role that utilized his natural history expertise. However, he eventually resigned from this position and returned to England in 1863, settling in London. He continued to publish occasional papers on natural history, particularly conchology.

In his later years, Angas suffered from poor health. He devoted time to organizing his extensive collection of drawings, papers, and family archives, possibly with a view towards further publication or securing his legacy. There are accounts suggesting some complexity in his later personal dealings, particularly concerning his secretary, Henry Hussey, and the management of his affairs, though details remain somewhat obscure. George French Angas died in London on October 8, 1886.

Today, Angas's legacy is multifaceted. His original watercolours are highly sought after by collectors and institutions, admired for their artistic merit and historical significance. His illustrated books remain landmark publications in the visual history of Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. They are indispensable resources for historians, anthropologists, and art historians studying the colonial period and the Indigenous cultures he depicted.

However, contemporary scholarship approaches his work with a critical awareness of the colonial context. While acknowledging the documentary value, analyses now also focus on the power dynamics inherent in his representations, the influence of European stereotypes, and the ways his work contributed to the colonial project of 'knowing' and categorizing Indigenous peoples. His art serves as a powerful reminder of the complexities of cross-cultural encounters during the age of empire.

Conclusion: A Prolific Chronicler of Empire

George French Angas was a remarkably prolific and versatile figure whose life and work bridged the worlds of art, science, and exploration. Driven by artistic ambition and an insatiable curiosity, he travelled to the frontiers of the British Empire, dedicating himself to documenting the landscapes, natural history, and Indigenous cultures he encountered with exceptional skill and detail. His major illustrated volumes stand as monumental achievements of 19th-century publishing and visual ethnography.

His legacy remains significant, though complex. Angas's watercolours and lithographs provide an unparalleled visual record of South Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa during a critical period of colonial expansion and cultural transformation. They offer invaluable insights for understanding the past. Yet, his work must be viewed through the lens of its time, recognizing the inherent colonial perspectives and biases that shaped his representations. As an artist, explorer, naturalist, and ethnographer, George French Angas left behind a rich and challenging body of work that continues to provoke study, admiration, and critical reflection.