William Charles Piguenit stands as a foundational figure in the annals of Australian art history. Celebrated as arguably the first significant professional painter born on Australian soil, his oeuvre is intrinsically linked with the majestic and often untamed landscapes of Tasmania, and later, mainland Australia. Piguenit's work, deeply rooted in the Romantic tradition, captured the sublime beauty, inherent drama, and profound solitude of the natural world, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's artistic consciousness. His journey from a government draughtsman to a revered artist charts a course of dedication, exploration, and a unique vision that helped define a distinctly Australian approach to landscape art.

Early Life and Formative Influences

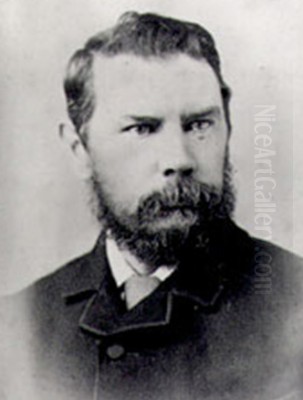

Born in Hobart, Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania), on August 27, 1836, William Charles Piguenit's lineage was a blend of the colonial experience. His father, Frederick Le Geyt Piguenit, of Norman-French descent, had been transported as a convict, while his mother, Mary Ann née Igglesden, was a free immigrant from Kent, England. This complex family background did not hinder his mother's ambition for her children; she ensured William received a sound education, which included instruction in French, music, and, crucially, drawing. This early exposure to the arts likely sowed the seeds for his future vocation.

In 1850, at the young age of 14, Piguenit joined the Tasmanian Lands and Survey Department as a draughtsman. This role, which he held for over two decades, was profoundly influential. It provided him with unparalleled opportunities to venture into the remote and rugged interior of Tasmania. These survey expeditions, often arduous and demanding, allowed him to witness firsthand the island's dramatic mountain ranges, pristine lakes, and dense forests – landscapes that would become the cornerstone of his artistic output. His meticulous training in cartography and technical drawing honed his observational skills and precision, qualities that would later underpin the detailed realism within his romantic visions.

During his time at the Survey Department, Piguenit began to cultivate his artistic talents more seriously. He received some instruction in painting from the Scottish-born artist Frank Dunnett, who was active in Hobart. He also learned the techniques of printmaking, including etching, from artists such as Dunnett and Robin Vaughan Hood. These early lessons, combined with his innate talent and the direct inspiration of the Tasmanian wilderness, laid the groundwork for his distinctive style.

Transition to a Professional Artist

The call of art eventually became too strong to ignore. In 1872, after twenty-two years of service, Piguenit resigned from his secure government position to dedicate himself entirely to painting. This was a bold move in colonial Australia, where the pursuit of art as a full-time profession was fraught with uncertainty. He initially focused on the landscapes he knew best, particularly the wild, untamed regions of southwestern Tasmania, such as Port Davey, Lake Pedder, and the Western Tiers.

His early works from this period began to attract attention. He exhibited with the Victorian Academy of Arts in Melbourne and the New South Wales Academy of Arts (later the Art Society of New South Wales) in Sydney. His deep understanding of Tasmanian topography, combined with a burgeoning romantic sensibility, set his work apart. He was not merely transcribing scenery; he was imbuing it with mood, atmosphere, and a sense of the sublime, echoing the European Romantic painters like J.M.W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich, though developed in a distinctly Australian context.

Piguenit’s commitment to his subject matter was profound. He was an avid explorer and often undertook challenging journeys to remote locations to sketch and gather material for his studio paintings. This direct engagement with nature was crucial to the authenticity and power of his work. He was known to camp for extended periods in harsh conditions, patiently observing the changing light and weather patterns that so dramatically shaped the landscapes he depicted.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Piguenit's artistic style is best described as Romantic Realism. His paintings exhibit a meticulous attention to geological detail and botanical accuracy, a legacy of his draughtsmanship. However, this realism is consistently infused with a powerful Romantic sensibility. He sought to convey the grandeur, mystery, and sometimes melancholic beauty of the Australian wilderness. His compositions often feature vast, panoramic vistas, towering mountains shrouded in mist, serene lakes reflecting dramatic skies, and deep, shadowy forests.

A key characteristic of his work is the masterful use of light and atmosphere. Piguenit was adept at capturing the ethereal effects of dawn and dusk, the dramatic interplay of sunlight and shadow, and the brooding quality of approaching storms. His skies are rarely passive backdrops; they are active participants in the drama of the landscape, often filled with swirling clouds or suffused with a soft, crepuscular glow. This emphasis on atmospheric effects contributed significantly to the emotional impact of his paintings, evoking feelings of awe, solitude, and contemplation.

While his European Romantic predecessors like John Constable or Théodore Rousseau of the Barbizon School often included figures to animate their landscapes or suggest a pastoral ideal, Piguenit’s works frequently emphasize the vastness and emptiness of the Australian wilderness, with human presence either absent or dwarfed by the scale of nature. This approach highlighted the untamed character of the land and perhaps reflected a colonial awe in the face of a continent still being "discovered" by Europeans. His contemporary in Australia, Eugene von Guérard, also shared this Romantic inclination for depicting the sublime grandeur of the Australian landscape, often with meticulous detail.

Piguenit also experimented with monochrome, producing striking works in sepia or grisaille that emphasized tonal contrasts and compositional strength. These works, often based on his field sketches, possess a raw immediacy and demonstrate his command of form and value.

Landmark Works and Major Achievements

Several paintings stand out as landmarks in Piguenit’s career, defining his contribution to Australian art.

Mount Olympus, Tasmania, with Lake St. Clair in the Foreground (c. 1875): This iconic work is one of his most celebrated Tasmanian landscapes. It beautifully captures the serene majesty of the scene, with the distinctive peak of Mount Olympus reflected in the calm waters of Lake St. Clair. The painting’s significance was recognized when it became the first oil painting by an Australian-born artist to be purchased by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1875, a major endorsement of his talent.

The Source of the Derwent, Tasmania (1887): This painting depicts the rugged, mountainous region where the Derwent River originates. It showcases Piguenit's ability to convey the wildness and remoteness of the Tasmanian highlands, with dramatic cloud formations and a sense of profound isolation. The work was highly praised for its fidelity to nature and its evocative atmosphere.

The Flood in the Darling 1890 (painted 1895): After moving to Sydney in the 1880s, Piguenit began to explore the landscapes of New South Wales. This painting, depicting the aftermath of a major flood on the Darling River, is a powerful representation of the forces of nature. The vast expanse of water, the debris-strewn landscape, and the dramatic sky create a scene of both devastation and solemn beauty. This work earned Piguenit the prestigious Wynne Prize for landscape painting in 1901, a significant accolade in his career.

Mount Kosciusko (1903): Commissioned by the trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, this monumental painting of Australia's highest peak was intended to be a symbolic representation of the newly federated nation. Piguenit undertook an arduous expedition to the Snowy Mountains to gather material for the work. The resulting canvas is a majestic panorama, capturing the grandeur and alpine beauty of Mount Kosciusko, and it became one of his most famous works.

Beyond these, Piguenit produced a substantial body of work, including depictions of the Lane Cove and Hawkesbury Rivers near Sydney, and various other Tasmanian scenes. He also contributed illustrations to significant publications, such as the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia (1886-88), which brought his imagery to a wider audience. His contemporary, Louis Buvelot, a Swiss-born artist who settled in Victoria, was also instrumental in popularizing landscape painting in Australia, advocating for plein-air sketching, a practice Piguenit also embraced in his fieldwork.

Travels, Recognition, and Later Career

In the 1880s, Piguenit relocated from Tasmania to Sydney, settling in Hunters Hill. This move broadened his subject matter to include the landscapes of New South Wales. He became an active member of the Art Society of New South Wales, serving on its council and contributing regularly to its exhibitions. His work was also shown in Melbourne and other Australian cities.

Piguenit sought international recognition for Australian art. He travelled to Europe in 1898 and again in 1900, visiting galleries in London and Paris and exhibiting his own work. He showed paintings at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the Paris Salon, receiving an honourable mention at the Salon in 1900. These European excursions allowed him to see firsthand the works of contemporary European masters and undoubtedly enriched his artistic perspective, though his core style remained firmly rooted in his Australian experiences.

His contemporaries in Australia included the artists of the Heidelberg School, such as Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Charles Conder, and Frederick McCubbin. While Piguenit’s meticulous, romantic style differed from their more impressionistic approach focused on capturing fleeting effects of light and everyday life, he was a respected elder figure in the Australian art scene. His dedication to depicting the uniquely Australian landscape, albeit through a different stylistic lens, paralleled their own nationalistic artistic concerns. Other notable landscape painters of the period whose work provides a comparative context include John Ford Paterson and later, Hans Heysen, who would continue the tradition of celebrating the Australian bush.

Despite some contemporary critics occasionally finding his work lacking in "breadth" or "atmosphere" compared to more impressionistic styles, Piguenit's paintings were generally well-received for their truthfulness to nature, their technical skill, and their evocative power. His success, including the Wynne Prize and the AGNSW commission for Mount Kosciusko, solidified his reputation as one of Australia's foremost landscape painters. He was also a mentor to younger artists, and his home in Hunters Hill became a meeting place for those interested in the arts.

Piguenit's Place Among Contemporaries

When situating Piguenit within the broader art world, it's important to acknowledge the influences and parallels. His Romanticism, while developed in Australia, connects to the wider 19th-century movement. The awe for nature seen in the Hudson River School painters in America, such as Albert Bierstadt or Frederic Edwin Church, who depicted the grand wilderness of the New World, finds an echo in Piguenit's portrayal of Tasmania's untamed beauty.

In Australia, he followed in the footsteps of earlier colonial artists like John Glover, who had also been captivated by the Tasmanian landscape, and Conrad Martens, whose romantic watercolours and oils documented the Sydney region and beyond. However, Piguenit, as a native-born artist, brought a different sensibility, perhaps a deeper, more intrinsic connection to the land he depicted.

While the Heidelberg School artists were gaining prominence with their lighter palettes and focus on capturing the unique Australian light and rural life, Piguenit continued to explore the more sublime, often darker and more dramatic aspects of the wilderness. His work offered a counterpoint to their sun-drenched impressionism, emphasizing the ancient, enduring, and sometimes formidable character of the Australian continent. Artists like Walter Withers, another member of the Heidelberg School, also focused on landscape but often with a more melancholic or tonalist approach that shared some atmospheric qualities with Piguenit's work, despite stylistic differences.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

William Charles Piguenit passed away at his home in Hunters Hill, Sydney, on July 17, 1914. He left behind a significant legacy as a pioneer of Australian landscape painting. His dedication to his craft, his adventurous spirit in seeking out remote and challenging subjects, and his ability to convey the profound beauty and power of the Australian wilderness established him as a key figure in the nation's art history.

His works are held in major public collections across Australia, including the National Gallery of Australia, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the National Gallery of Victoria, the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, and numerous regional galleries. They continue to be admired for their technical accomplishment, their historical significance, and their evocative portrayal of landscapes that are central to Australia's natural heritage.

Piguenit's contribution was not just in the paintings themselves, but in helping to foster an appreciation for the Australian landscape as a worthy subject for serious artistic endeavour. He demonstrated that an artist born and trained in Australia could achieve national and even international recognition. His romantic vision of the wilderness, while perhaps less fashionable during the ascendancy of modernism in the 20th century, has seen a resurgence of appreciation as contemporary audiences reconnect with the power of nature and the importance of environmental consciousness.

In conclusion, William Charles Piguenit was more than just a skilled painter; he was an interpreter of the Australian soul as expressed through its ancient and majestic landscapes. His art invites contemplation on the relationship between humanity and the natural world, a theme that remains profoundly relevant today. His legacy endures, securing his place as a vital and respected figure in the story of Australian art.