John Gould (1804-1881) stands as one of the most significant figures in the history of ornithology and a prolific publisher of exquisitely illustrated bird books during the 19th century. His life's work not only vastly expanded the scientific understanding of avian species across the globe but also produced a legacy of artistic masterpieces that continue to be admired for their beauty, accuracy, and ambition. As an ornithologist, taxidermist, and entrepreneurial publisher, Gould carved a unique niche for himself, bridging the worlds of scientific discovery and fine art. His influence extended to contemporaries like Charles Darwin and shaped the course of natural history illustration for generations.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born on September 14, 1804, in Lyme Regis, Dorset, England, John Gould's early life was modest. His father, John Gould Sr., was a gardener, and young John initially followed in his footsteps. This horticultural background provided him with a foundational understanding of the natural world and keen observational skills. For a period, his father held a position on the gardening staff at Windsor Castle, and it was here, amidst the royal estates, that Gould's fascination with birds and taxidermy began to blossom.

He received little formal schooling, a common circumstance for those of his social standing at the time. However, Gould was an avid self-learner, driven by an insatiable curiosity about nature. His practical skills in taxidermy developed rapidly, and by his early twenties, he was already gaining a reputation for his adeptness in preserving and mounting animal specimens, particularly birds. This skill was not merely technical; it required an intimate understanding of avian anatomy and posture to create lifelike representations.

In 1827, a pivotal opportunity arose when Gould was appointed as the first "Curator and Preserver" (essentially, chief taxidermist) to the museum of the recently founded Zoological Society of London. This position placed him at the heart of the burgeoning scientific community in London, giving him access to a wealth of new and exotic specimens arriving from all corners of the British Empire and beyond. It was a role that would define the trajectory of his career.

The Zoological Society and Early Publications

At the Zoological Society, Gould was immersed in a vibrant intellectual environment. He worked under the guidance of prominent naturalists like Nicholas Aylward Vigors, the Society's Secretary, who encouraged his scientific pursuits. His role involved preparing and cataloging the Society's growing collection of bird skins and mounted specimens. This hands-on experience was invaluable, allowing him to study a diverse array of avian forms firsthand.

It was during this period that Gould conceived the idea of producing his own illustrated ornithological works. His ambition was fueled by the availability of exciting new species and his desire to share these discoveries with a wider audience. In 1829, he married Elizabeth Coxen, a governess with remarkable artistic talent. This union proved to be a cornerstone of his future success. Elizabeth became his principal artist, translating his rough sketches and scientific insights into the delicate and detailed illustrations that would grace his publications.

Gould's first major independent venture was "A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains" (1830-1832). This work, featuring 80 hand-colored lithographs, showcased birds largely new to European science, collected in the Himalayas. Elizabeth Gould drew the birds onto the lithographic stones, and the plates were then hand-colored by a team of colorists under their supervision. The book was a critical and commercial success, establishing Gould's reputation as a serious ornithologist and a capable publisher. It set the template for his future folio productions: large-format volumes issued in parts to subscribers, containing stunning, life-sized (where possible) illustrations accompanied by descriptive text.

The Crucial Partnership: John and Elizabeth Gould

The collaboration between John and Elizabeth Gould was fundamental to the success of his early and most iconic works. While John possessed the scientific knowledge, the entrepreneurial drive, and the initial sketching ability, Elizabeth possessed the refined artistic skill to bring the birds to life on the page. She quickly mastered the relatively new technique of lithography, reportedly receiving lessons from Edward Lear, who was himself an accomplished bird artist.

Elizabeth's contribution cannot be overstated. She was responsible for drawing hundreds of plates for works like "A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains," "The Birds of Europe" (1832-1837), and the initial parts of "The Birds of Australia." Her illustrations were praised for their accuracy, delicacy, and the lifelike quality she imparted to the subjects. She often depicted the birds in naturalistic poses, sometimes with nests, eggs, or characteristic foliage, adding to the scientific and aesthetic value of the plates.

Beyond her artistic contributions, Elizabeth was a devoted wife and mother, accompanying John on his arduous two-year expedition to Australia. The strain of constant work and child-rearing, however, took its toll. Tragically, Elizabeth Gould died in 1841 at the young age of 37, shortly after their return from Australia and following the birth of their eighth child. Her death was a profound personal and professional loss for John Gould. He wrote, "the companion of my travels, the solace of my griefs & the sharer of my successes." Though he would employ other talented artists to continue his work, Elizabeth's artistic spirit remained deeply embedded in the Gouldian legacy.

The Australian Odyssey and its Impact

Perhaps John Gould's most ambitious undertaking was his work on the avifauna of Australia. Recognizing the continent's unique and largely undocumented birdlife, Gould and Elizabeth, along with their eldest son and his collector John Gilbert, embarked on an expedition to Australia in 1838, remaining there until 1840. This was a bold move, requiring significant personal and financial investment.

During their time in Australia, Gould and Gilbert traveled extensively, collecting thousands of bird and mammal specimens, eggs, and nests, and making copious notes on their behavior and habitats. Gould's direct field experience was crucial, allowing him to observe many species in their natural environment. He identified and described numerous species new to science. John Gilbert proved to be an exceptionally skilled and dedicated collector, continuing to work for Gould in Australia after Gould's return to England, until Gilbert's tragic death during Ludwig Leichhardt's expedition in 1845.

The fruits of this expedition were published in the monumental "The Birds of Australia," issued in 36 parts between 1840 and 1848, comprising seven large folio volumes with 681 hand-colored plates. A supplementary volume was published later. Elizabeth Gould completed many of the early plates before her death, after which Henry Constantine Richter became Gould's primary artist for this and subsequent works. "The Birds of Australia" was a landmark achievement, providing the first comprehensive illustrated account of Australian birds and remains a foundational text in Australian ornithology. It also included descriptions of many new kangaroo species in an accompanying work, A Monograph of the Macropodidae, or Family of Kangaroos.

Major Ornithological Works: A Legacy in Folio

John Gould's publishing career spanned five decades, during which he produced an astonishing series of folio volumes that are now highly prized by collectors and institutions. Each work was a testament to his scientific acumen, artistic vision, and entrepreneurial skill.

"The Birds of Europe" (1832-1837), in five volumes with 448 plates, was an early success that aimed to depict all known European bird species. Elizabeth Gould was the primary artist for this series, and it showcased her growing proficiency in lithography. The work was well-received and helped solidify Gould's international reputation. It competed with, and in many ways surpassed, similar contemporary European works by figures like Coenraad Jacob Temminck and Sir William Jardine with Prideaux John Selby.

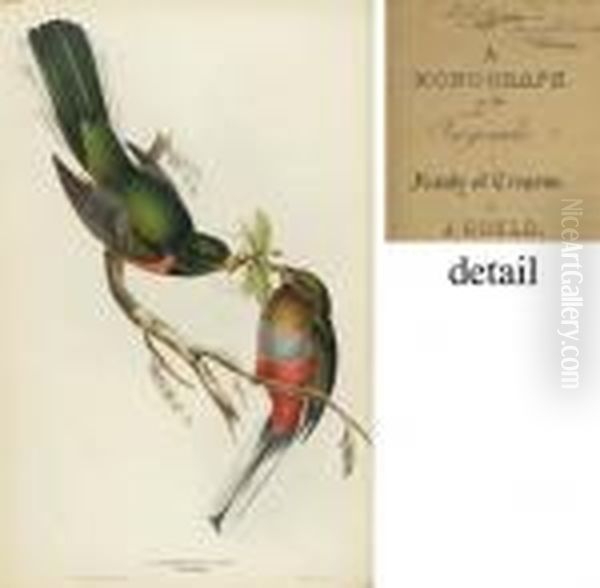

"A Monograph of the Ramphastidae, or Family of Toucans" (1833-1835, with a second, expanded edition in 1852-1854) focused on the spectacularly beaked toucans of Central and South America. The vibrant colors and exotic forms of these birds were perfectly suited to Gould's illustrative style. Edward Lear contributed significantly to the first edition, producing some of his finest bird illustrations.

"A Monograph of the Trogonidae, or Family of Trogons" (1835-1838, second edition 1858-1875) depicted another group of brilliantly plumaged tropical birds. The iridescent feathers of trogons and quetzals were a challenge for the artists and colorists, but the resulting plates are among Gould's most beautiful.

Following "The Birds of Australia," Gould embarked on "A Monograph of the Odontophorinae, or Partridges of America" (1844-1850), showcasing the New World quails. H.C. Richter was the principal artist for this work.

One of his most celebrated and visually stunning works was "A Monograph of the Trochilidae, or Family of Humming-Birds" (1849-1861). This massive undertaking, eventually comprising six volumes (including a supplement completed after his death by Richard Bowdler Sharpe and illustrated by William Matthew Hart and Joseph Smit), contained 418 plates. Gould had a particular passion for hummingbirds, amassing an unparalleled collection of specimens. He even exhibited his stuffed hummingbird collection to great acclaim at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The plates for "Humming-Birds" are renowned for their dazzling depiction of iridescent plumage, often enhanced with gold leaf and shimmering paints to capture the birds' jewel-like quality. Richter and Hart were the main artists.

"The Birds of Asia" (1850-1883), another vast project in seven volumes with 530 plates, was left unfinished at Gould's death and completed by R. Bowdler Sharpe. It aimed to document the diverse avifauna of the Asian continent, with illustrations by Richter, Josef Wolf (who contributed some particularly dynamic plates), and W.M. Hart.

"The Birds of Great Britain" (1862-1873), in five volumes with 367 plates, was perhaps his most popular work in his home country. Unlike some of his earlier works that focused on exotic species, this series depicted familiar British birds. Gould took particular pride in this work, emphasizing the depiction of young birds and nests, reflecting a growing interest in life histories. Josef Wolf and H.C. Richter were the primary artists, though Gould himself provided many detailed sketches.

His final major work, "The Birds of New Guinea and the Adjacent Papuan Islands" (1875-1888), was also completed by Sharpe after Gould's death, with W.M. Hart as the principal artist. This series showcased the fantastically plumed birds-of-paradise and other exotic species from the Australasian region.

Artistic Style and Techniques

John Gould was not merely a publisher; he was the artistic director of his works. He would typically make initial sketches from specimens, often indicating pose and key features. These sketches were then passed to his artists – Elizabeth Gould, Edward Lear, H.C. Richter, Josef Wolf, or William Hart – who would develop them into finished drawings on lithographic stones.

Lithography was the chosen medium for Gould's plates. This planographic printing process allowed for fine detail and subtle gradations of tone. Once the black and white lithographs were printed, they were meticulously hand-colored by a team of skilled artisans. Gould maintained high standards for this coloring process, ensuring accuracy and vibrancy. The use of gum arabic to add gloss to dark areas, and metallic paints or gold leaf for iridescent effects (especially in the hummingbirds), were characteristic touches that enhanced the visual appeal and realism of the plates.

Gould's illustrations are characterized by:

1. Scientific Accuracy: Great care was taken to depict plumage details, beak and leg structure, and proportions correctly.

2. Lifelike Poses: Birds were often shown in dynamic or characteristic poses, rather than stiffly profiled, reflecting Gould's field observations and taxidermy skills.

3. Naturalistic Settings: While the primary focus was the bird, many plates included elements of habitat, such as branches, flowers, or nests, adding context and aesthetic appeal.

4. Compositional Skill: The birds were usually arranged effectively on the page, often in pairs (male and female) or family groups.

5. Vibrant Color: The hand-coloring was generally rich and true to life, contributing significantly to the beauty of the works.

While John James Audubon, his American contemporary, often favored more dramatic and sometimes anthropomorphic poses in his aquatints, Gould's lithographs generally maintained a more restrained, scientifically focused naturalism, though still imbued with considerable artistic grace.

Collaborators and Contemporaries

John Gould's immense output was made possible by a team of talented individuals. His wife, Elizabeth Gould (née Coxen), was his first and arguably most important artistic collaborator. Her delicate and accurate drawings set the standard for the early works.

Edward Lear (1812-1888), famous today for his nonsense verse, was a brilliant natural history artist in his youth. He worked for Gould on "Birds of Europe" and "A Monograph of the Ramphastidae," and his distinctive style, characterized by a strong sense of form and personality in his subjects, influenced Elizabeth's lithographic technique.

After Elizabeth's death, Henry Constantine Richter (c.1821-1902) became Gould's principal artist for over three decades, illustrating thousands of plates for "The Birds of Australia," "Humming-Birds," "Birds of Asia," and "Birds of Great Britain," among others. Richter capably continued the established Gouldian style.

Josef Wolf (1820-1899), a German artist who moved to London, was considered one of the finest animal painters of his era. He contributed a number of plates to "Birds of Asia" and "Birds of Great Britain." His work is noted for its anatomical precision and dynamic portrayal of animals in their natural environments. Wolf was highly respected by his peers, including Sir Edwin Landseer.

William Matthew Hart (1830-1908) began working for Gould as a colorist and later became a key lithographer and artist, particularly for the supplement to "Humming-Birds" and "The Birds of New Guinea." He was responsible for completing many of Gould's later projects.

Richard Bowdler Sharpe (1847-1909), an ornithologist at the British Museum, was a close associate of Gould in his later years. Sharpe completed several of Gould's works after his death, writing the accompanying text and overseeing their publication.

Gould also relied on a network of collectors worldwide, most notably John Gilbert (1812?-1845) in Australia, whose tireless efforts provided many of the specimens for "The Birds of Australia." Other contemporary ornithologists and naturalists with whom Gould interacted, corresponded, or sometimes competed included Sir William Jardine, Prideaux John Selby, Charles Lucien Bonaparte, Coenraad Jacob Temminck, and William Swainson. While John James Audubon (1785-1851) was producing his monumental Birds of America using aquatints, Gould was pioneering large-scale ornithological illustration using lithography in Britain. They were aware of each other's work, representing the two giants of bird illustration of their time.

Gould and Darwin: A Pivotal Relationship

John Gould played a crucial, if sometimes under-acknowledged, role in the development of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. When Darwin returned from the voyage of HMS Beagle in 1836, he entrusted his bird specimens to Gould for identification.

In early 1837, Gould examined Darwin's finches from the Galápagos Islands. Darwin had initially misidentified them, not realizing their close relationship or their significance. Gould recognized that these birds, despite their variations in beak size and shape, constituted a distinct group of finches, comprising several new species unique to the Galápagos. He also correctly identified Darwin's Galápagos mockingbirds as distinct species, not mere varieties, and pointed out that different islands often harbored different species.

This information was a revelation to Darwin and a key piece of evidence that led him to ponder the transmutation of species. Gould's identification of the finches (which became known as "Darwin's finches") and the geographical distribution of related but distinct species provided strong support for the idea that species could adapt and diverge from a common ancestor. Gould also identified Darwin's specimen of a smaller rhea from Patagonia as a new species, Rhea darwinii (now Rhea pennata), distinct from the common Greater Rhea, further highlighting geographical speciation.

Gould presented these findings at meetings of the Zoological Society, and his work on Darwin's specimens was published in The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. While Gould himself was not an evolutionist in the Darwinian sense, his meticulous taxonomic work provided critical data for Darwin's revolutionary ideas.

Later Life, Legacy, and Recognition

John Gould remained incredibly productive throughout his life. He was a shrewd businessman, successfully managing the complex logistics and finances of his large-scale publishing ventures. His books were sold by subscription, primarily to wealthy individuals, learned societies, and libraries, due to their considerable cost.

He received numerous accolades for his contributions to science. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1843, a prestigious honor. Many bird species were named after him (e.g., Gould's Sunbird, Gould's Petrel) and his wife (e.g., Mrs. Gould's Sunbird), a testament to their impact on ornithology. His collection of hummingbirds, numbering over 5,000 specimens, was exhibited to great public and royal acclaim.

Despite his scientific achievements and the artistic merit of his publications, Gould's personal life was marked by tragedy. The early death of his wife Elizabeth was a severe blow, and he also outlived several of his children. He never remarried, dedicating himself to his work.

John Gould died in London on February 3, 1881, at the age of 76. He was working on "The Birds of New Guinea" and other projects until the very end. His vast stock of publications, drawings, and specimens was eventually acquired by various institutions and private collectors, with a significant portion of his bird collection going to the British Museum (Natural History), now the Natural History Museum, London.

Controversies and Criticisms

Despite his immense success, John Gould was not without his critics, and certain aspects of his career have attracted controversy. Some contemporaries found him to be a sharp businessman, sometimes perceived as overly commercial or self-promoting. There were occasional disputes over the naming of species or the priority of discoveries.

One persistent criticism was that Gould did not always adequately acknowledge the contributions of his artists and collaborators in the text of his works, although their names usually appeared on the plates themselves. While Elizabeth's role was significant, the primary authorship and scientific credit invariably went to John.

Gould's relationship with the formal scientific establishment was sometimes complex. For instance, he was never elected to the British Ornithologists' Union (BOU), a fact some attribute to social snobbery within the organization, given Gould's relatively humble origins and his status as a "tradesman" (publisher and taxidermist) in the eyes of some gentleman-scholars. However, his fellowship in the much more prestigious Royal Society indicates his high standing in the broader scientific community.

The large-scale collection of specimens, a standard practice in 19th-century natural history, is viewed differently today through the lens of conservation ethics. While essential for scientific study at the time, the collection of numerous examples of rare species contributed to population declines in some cases, though Gould was by no means unique in this practice; it was the prevailing methodology of the era.

Enduring Influence

John Gould's legacy is monumental. His books remain among the most beautiful and comprehensive ornithological works ever produced. They are invaluable historical records of birdlife in the 19th century and continue to be sought after by collectors, admired by art lovers, and consulted by researchers.

His contributions to ornithology were profound. He described hundreds of new species, significantly advanced the understanding of global avifauna (particularly of Australia, Asia, and South America), and his work on Darwin's specimens played a vital role in the history of evolutionary biology.

Artistically, Gould set a new standard for natural history illustration. The "Gouldian style" – characterized by scientific accuracy, lifelike portrayal, and vibrant hand-coloring – influenced subsequent bird artists and publishers. His entrepreneurial model of producing high-quality, subscription-based folios was also influential, though few could match his scale or sustained output.

Today, original Gould plates are highly collectible and can be found in major libraries, museums, and private collections around the world. Exhibitions of his work continue to draw admiration, and digital reproductions have made his stunning illustrations accessible to a global audience, ensuring that the beauty and scientific importance of John Gould's avian world will endure.

Conclusion

John Gould was a remarkable figure: a largely self-taught naturalist who rose from humble beginnings to become a dominant force in Victorian ornithology and a master publisher of natural history art. His energy, ambition, scientific acumen, and artistic vision combined to produce a body of work that is staggering in its scope and breathtaking in its beauty. Through his magnificent folios, he not only documented the avian diversity of the world but also created an enduring artistic legacy that continues to inspire awe and appreciation, securing his place as one of the true giants in the history of natural science and art.