Mark Catesby stands as a monumental figure in the annals of natural history and art, a man whose passion for the nascent wilderness of colonial America led to one of the most significant illustrated works of the 18th century. Born in England, his intrepid voyages across the Atlantic and his meticulous documentation of the flora and fauna of the New World provided Europeans with their first comprehensive visual and scientific understanding of its biological riches. His work not only advanced scientific knowledge but also established a new benchmark in natural history illustration, blending artistic sensibility with empirical observation.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Mark Catesby was born in Castle Hedingham, Essex, England, with his baptism recorded on March 24, 1683. His father, John Catesby, was a local lawyer and politician, serving as mayor of Sudbury in Suffolk, and his mother was Elizabeth Jekyll. The Jekyll family was well-established, and through his mother's uncle, Nicholas Jekyll, a renowned antiquarian and historian of Essex, Catesby likely gained early exposure to scholarly pursuits and the importance of meticulous recording. This familial background, combining legal precision with an appreciation for history and collection, may have subtly shaped his future endeavors.

Though details of his formal education are scarce, it is widely believed that Catesby developed an early and profound interest in the natural world. He became acquainted with prominent naturalists of his time, most notably John Ray, a leading figure in English botany and zoology, often considered the father of English natural history. Ray lived near Catesby's birthplace, and their association undoubtedly fueled Catesby's passion and provided him with a foundational understanding of systematic biology. Ray's emphasis on direct observation and detailed description would become hallmarks of Catesby's own work. Other influences may have included the burgeoning culture of collecting and cataloging natural curiosities prevalent among the English gentry and scientific community.

Catesby's early life was also marked by a connection to the Americas through his sister, Elizabeth, who married Dr. William Cocke. Dr. Cocke was a physician and a member of the Council of Virginia, and this familial tie would prove instrumental in facilitating Catesby's first journey to the New World. The prospect of exploring a land teeming with unfamiliar plants and animals, largely undocumented by European science, must have been an irresistible allure for the aspiring naturalist.

The First American Sojourn: Virginia

In 1712, at the age of 29, Mark Catesby embarked on his first voyage to America, arriving in the colony of Virginia. He resided primarily with his sister Elizabeth and her husband, Dr. William Cocke, in Williamsburg. This initial trip, lasting seven years until 1719, was largely self-funded and driven by his personal curiosity. Virginia, at this time, was a well-established colony, but its hinterlands remained a frontier, offering a wealth of botanical and zoological subjects new to European eyes.

During these seven years, Catesby immersed himself in collecting botanical specimens and seeds. He sent many of these back to England, notably to figures like Samuel Dale, a botanist and apothecary, and Thomas Fairchild, a nurseryman in Hoxton. His collections also reached the hands of Sir Hans Sloane, a prominent physician and collector whose vast holdings would later form the nucleus of the British Museum, and William Sherard, a distinguished botanist who maintained an extensive herbarium. The quality and novelty of Catesby's specimens quickly garnered attention and respect within London's scientific circles.

While in Virginia, Catesby also began to sketch the plants and animals he encountered. Though not yet the accomplished artist he would become, these early forays into illustration were crucial for his development. He learned to capture the forms and colors of his subjects, laying the groundwork for his later, more ambitious artistic endeavors. This period was one of exploration and learning, allowing him to become familiar with the American landscape and its inhabitants, both human and wild. He interacted with colonists and likely learned from Native Americans about local flora and fauna, knowledge that would inform his later writings. His return to England in 1719 was not an end, but rather a prelude to a more focused and ambitious undertaking.

The Second Expedition: A Comprehensive Survey

Upon his return to England in 1719, Catesby's collections and observations had sufficiently impressed influential members of the scientific community. Recognizing his dedication and the potential for a more systematic survey of American natural history, a group of patrons, including William Sherard, Sir Hans Sloane, and Francis Nicholson (then Governor of South Carolina), sponsored a second, more extensive expedition. This financial backing was crucial, allowing Catesby to dedicate himself fully to collecting, documenting, and drawing.

In 1722, Catesby set sail once more for America, this time heading further south to Carolina. He spent the majority of his time in what is now South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, venturing into remote areas and enduring the hardships of colonial frontier life. His explorations extended from Charles Town (Charleston) inland, up rivers, and through swamps and forests. He also spent nearly nine months in the Bahama Islands, significantly expanding the geographical scope of his study. This second journey lasted until 1726, though some accounts suggest he may have stayed longer, possibly until 1731, focusing on his artistic and observational work.

During this period, Catesby meticulously collected specimens of birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, insects, mammals, and plants. Crucially, he also made detailed drawings and watercolors from life, a practice that set his work apart. He understood the importance of observing organisms in their natural habitats, noting their behaviors, diets, and interactions with other species. This ecological approach was pioneering for its time. He learned from local inhabitants, including Native Americans and enslaved Africans, who possessed extensive knowledge of the local environment. This indigenous and local knowledge, though not always explicitly credited in the manner of modern science, undoubtedly enriched his understanding and is subtly woven into his observations.

The sheer volume of material he gathered – specimens, seeds, drawings, and notes – was astounding. He faced numerous challenges, from the practical difficulties of preserving specimens in a hot, humid climate to the dangers of travel in undeveloped territories. Yet, his determination to create a comprehensive record of the New World's natural history never wavered. The illustrations he produced during this period formed the core of his future masterpiece.

The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands

Upon his final return to England, Catesby faced the monumental task of organizing his vast collection of drawings and notes and preparing them for publication. His magnum opus, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (Latin title: Naturalis Historia Carolinae, Floridae, et Insularum Bahamensium), was to become the first major illustrated work on the flora and fauna of North America.

The publication was an ambitious and financially demanding project. To maintain artistic control and reduce costs, Catesby took the extraordinary step of learning the art of etching himself. This allowed him to transfer his original watercolor drawings onto copper plates for printing. He then personally supervised or undertook the hand-coloring of the printed plates, ensuring a degree of fidelity to his original observations. This hands-on approach was unusual for such a large-scale scientific publication and speaks to his dedication.

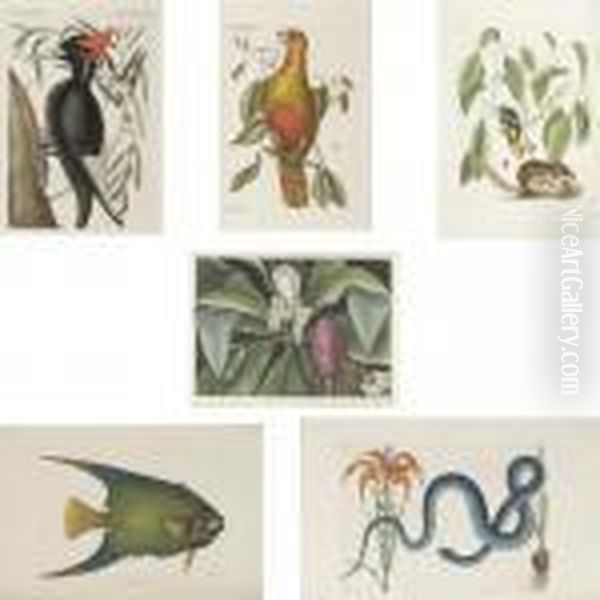

The work was published in installments, a common practice for expensive illustrated books at the time, making it more accessible to subscribers. The first volume appeared between 1729 and 1732 (though some sources cite 1731 as the start), with the second volume following between 1734 and 1743. An appendix, or Supplement, was published in 1747. In total, the completed work comprised 220 hand-colored plates, each accompanied by Catesby's descriptive text in both English and French, a nod to the international scientific community.

The plates depicted a wide array of life: 113 birds, 50 fish, 33 amphibians and reptiles, 9 mammals, and numerous insects, often shown alongside the plants with which they were associated. This practice of depicting animals within an ecological context – for example, a bird perched on a branch of a plant it might feed on or nest in – was a significant innovation. It moved beyond simple species portraiture to hint at the interconnectedness of nature, a concept that would later become central to the field of ecology.

Catesby's Natural History was a landmark achievement. It provided the first comprehensive, illustrated account of the natural productions of a significant portion of southeastern North America and the Bahamas. Its impact was immediate and profound, influencing subsequent naturalists and artists and serving as a crucial reference for scientists, including the great Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who cited Catesby extensively in his Systema Naturae when assigning binomial names to many American species.

Artistic Style and Innovations

Mark Catesby's artistic style is characterized by a directness and a commitment to naturalism, albeit one that sometimes appears charmingly naive to modern eyes accustomed to photorealism or the more polished techniques of later artists like John James Audubon. His primary goal was scientific accuracy in depicting the form and color of his subjects, often at the expense of complex compositions or sophisticated perspective.

One of his most significant innovations was the consistent depiction of animals in conjunction with plants from their habitat. For instance, he would show a bird perched on a specific tree whose fruit it consumed, or a snake entwined in a particular vine. This ecological approach was revolutionary. While earlier artists like Maria Sibylla Merian had depicted insects with their host plants, Catesby extended this concept more broadly across the animal kingdom, particularly with birds. This contextualization provided valuable information about the species' life history and environment.

Catesby was largely self-taught as an artist and etcher. While his figures might occasionally lack the dynamic poses or anatomical precision of academically trained artists, they possess a vitality and an authenticity born from direct observation in the field. He captured the characteristic features and vibrant colors of species previously unknown to Europeans. His compositions are often simple, focusing the viewer's attention on the subject. He sometimes employed a somewhat flattened perspective, which he argued was sufficient for species identification.

His decision to learn etching to produce his own plates was a testament to his dedication. While some critics noted that his etchings were not as refined as those of professional engravers, this direct involvement ensured that his artistic vision was translated more faithfully than if intermediaries had been involved. The hand-coloring, often done by Catesby himself or under his close supervision, further enhanced the plates' scientific and aesthetic value.

Catesby's work also occasionally displays a subtle humor or keen design sense. For example, he might depict a creature in a slightly whimsical pose or strategically break a branch in a composition to better reveal an animal's features. These touches add a personal dimension to his scientific illustrations. Despite any perceived technical shortcomings, the overall impact of his art was immense, setting a new standard for natural history illustration and profoundly influencing the way nature was depicted. His work directly inspired later ornithological artists like George Edwards and, through him, the lineage leading to Audubon.

Catesby and His Contemporaries

Mark Catesby operated within a vibrant and interconnected community of scientists, patrons, and fellow naturalists in 18th-century London, which was a major center for scientific inquiry. His interactions with these contemporaries were crucial for his expeditions, the publication of his work, and the dissemination of his findings.

Sir Hans Sloane was a pivotal figure. A wealthy physician and an avid collector, Sloane was a key sponsor of Catesby's second voyage. His vast collections, which included specimens sent by Catesby, formed the foundation of the British Museum. William Sherard, another important patron, was a leading botanist who recognized Catesby's potential and helped secure funding. Sherard's own extensive herbarium also benefited from Catesby's American collections.

Among fellow natural history illustrators, George Edwards was a significant contemporary and friend. Edwards, often called the "father of British ornithology," produced his own important illustrated works, A Natural History of Uncommon Birds and Gleanings of Natural History. He and Catesby influenced each other, and Edwards even assisted with some of Catesby's later plates. Edwards's work, like Catesby's, was used by Linnaeus. Some of Catesby's (and Edwards's) plates were later re-engraved and published by Johann Michael Seligmann in Germany, further broadening their European reach.

Catesby's work can be seen in the context of other natural history illustrators of the period. While he may not have had the delicate botanical artistry of someone like Georg Dionysius Ehret, or the entomological focus of Maria Sibylla Merian (whose work on the insects of Surinam predated Catesby's and set a precedent for studying exotic fauna), Catesby's comprehensive scope across different animal groups and his ecological approach were distinctive. He was also aware of earlier works, such as those by John White, who had depicted the flora and fauna of the Roanoke Colony in the late 16th century, and he may have seen illustrations by French botanical artists like Claude Aubriet or purchased works by figures like Joseph Pitton de Tournefort.

The scientific community eagerly received Catesby's Natural History. John Ray, his early mentor, had passed away before its publication, but Ray's emphasis on empirical study was clearly reflected in Catesby's approach. Carl Linnaeus, the architect of modern biological taxonomy, relied heavily on Catesby's descriptions and illustrations for classifying many North American species, frequently citing "Catesb. Carol." in his Systema Naturae. This cemented Catesby's scientific legacy.

Later naturalists and artists built upon the foundation Catesby laid. John James Audubon, the most famous American ornithological artist, undoubtedly knew Catesby's work, which set a precedent for ambitious, large-format publications on American birds. Alexander Wilson, another key figure in American ornithology, also followed in this tradition. William Bartram, an American naturalist who explored some of the same regions as Catesby a few decades later, continued the work of documenting the rich biodiversity of the American Southeast. Catesby's pioneering efforts thus resonated through generations of naturalists.

Later Life, Legacy, and Unresolved Questions

After the immense effort of producing and publishing The Natural History, Mark Catesby continued to live in London. He married Elizabeth Rowland on October 8, 1747, in St George's Chapel, Hyde Park Corner. Information about their children is limited, though it is known they had at least two who survived infancy. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1733, a prestigious recognition of his scientific contributions.

Despite the acclaim his work received, Catesby did not achieve great financial wealth from his publications. The production of such elaborate, hand-colored books was enormously expensive, and the subscription model, while helpful, did not always guarantee substantial profit for the author-artist. He lived modestly in his later years, continuing his interest in horticulture and maintaining a garden where he cultivated many of the American plants he had introduced to Britain.

Mark Catesby passed away in London on December 23, 1749, at the age of 66 (or 67, depending on the exact birth year interpretation). He was buried in the churchyard of St. Luke's Church, Old Street, London, though the exact location of his grave is now unknown, adding a touch of mystery to his final resting place. His will indicated plans for a final voyage to the Bahamas, a journey he was not destined to make.

Some historical details about Catesby's life remain subjects of minor debate or are not fully clarified. The precise date of his birth is often cited as March 24, 1683, based on his baptismal record, but some earlier sources suggested 1679 or 1682. Similarly, while December 23, 1749, is the generally accepted death date, other dates have occasionally appeared in historical literature. His mother, Elizabeth Jekyll Catesby, outlived him, passing away in 1753, at which point Mark Catesby's children inherited family property in Suffolk.

Catesby's legacy is profound and multifaceted. Scientifically, he provided the first comprehensive documentation of a vast array of North American species, many of which were new to science. His work was foundational for Linnaean taxonomy of American organisms. Artistically, he pioneered the ecological approach to natural history illustration, depicting species in their environmental context. He introduced numerous American plants to British gardens, contributing significantly to horticulture.

Though his fame was somewhat eclipsed in the 19th century by figures like Audubon, whose artistic style was more dramatic and technically polished, Catesby's importance has been increasingly recognized in modern times. His work is valued not only for its historical and scientific significance but also for its unique artistic charm and the sheer ambition of his undertaking. He remains a pivotal figure in the history of American natural science and art.

Collections and Modern Recognition

The original watercolor drawings that Mark Catesby created in America and which formed the basis for the etchings in his Natural History are treasured artifacts. A significant collection of these original artworks is held in the Royal Collection Trust in the United Kingdom, housed at Windsor Castle. These drawings offer a more immediate sense of Catesby's hand and his keen observational skills than the printed plates.

Copies of his monumental work, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, are held in esteemed libraries and institutions worldwide. The University of South Carolina Libraries, for instance, holds first, second, and third editions of the Natural History and has established the Catesby Centre, dedicated to promoting research and understanding of his work and its context. The Smithsonian Institution Libraries in Washington D.C. also possess a first edition.

Specimens collected by Catesby can still be found in historic collections. For example, plant specimens he gathered in South Carolina are preserved in the Sloane Herbarium at the Natural History Museum in London (which evolved from Sir Hans Sloane's original collections) and also at Oxford University. These physical remnants of his fieldwork are invaluable for botanical research.

Catesby's work continues to be the subject of exhibitions and scholarly study. Institutions like the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, and the Telfair Museums in Savannah, Georgia, have hosted exhibitions featuring his original works or printed plates, bringing his art and science to new audiences. The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. also includes Catesby's watercolors in its collection, recognizing their artistic merit.

Modern scholarship has increasingly highlighted Catesby's innovative approach, his role as a bridge between European science and the American wilderness, and the ecological insights embedded in his work. His contributions are celebrated not just for their pioneering nature but also for the dedication and personal endeavor they represented in an era when scientific exploration was fraught with challenges. His name is commemorated in the scientific names of several species, a lasting tribute to his impact on the study of natural history.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

Mark Catesby was more than just an explorer or an artist; he was a visionary who synthesized these roles to create a work of enduring scientific and aesthetic value. His journeys into the largely uncharted territories of colonial America, undertaken with remarkable dedication and an insatiable curiosity, yielded a treasure trove of information about the New World's biodiversity. The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands stands as a testament to his perseverance, his observational acuity, and his pioneering spirit.

He was among the first to systematically document and illustrate the flora and fauna of this vast region, providing a crucial foundation upon which later naturalists, including Linnaeus and Audubon, would build. His innovative approach of depicting organisms within their ecological settings presaged modern ecological thinking. By personally undertaking the arduous tasks of drawing, etching, and supervising the coloring of his plates, Catesby ensured a remarkable degree of fidelity to his original observations, bridging the gap between field experience and published knowledge.

While the scientific landscape has evolved dramatically since the 18th century, and artistic styles have changed, Mark Catesby's contributions remain foundational. He opened a window for Europeans onto the rich natural tapestry of America, and his work continues to inspire admiration for its beauty, its scientific importance, and the extraordinary human effort it represents. He rightfully holds his place as a key figure in the intertwined histories of art, science, and the exploration of the natural world.