John Jackson RA (31 May 1778 – 1 June 1831) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of British art, particularly renowned for his insightful and skilfully executed portraits during the late Georgian and Regency periods. An artist who rose from humble beginnings to become a respected member of the Royal Academy of Arts, Jackson's work is characterized by its honest depiction of character, rich colouring, and a technical proficiency that earned him numerous prestigious commissions. His legacy, though sometimes overshadowed by contemporaries like Sir Thomas Lawrence, remains vital for understanding the artistic currents of early 19th-century Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Lastingham, a small village in Yorkshire, England, in 1778, John Jackson's early life gave little indication of his future artistic prominence. His father was a village tailor, and young Jackson was initially apprenticed to the same trade. This practical, hands-on craft may have inadvertently honed a certain dexterity and attention to detail that would later serve him in his artistic pursuits. However, his innate passion for art soon became evident. Despite his father's disapproval of art as a viable profession, Jackson began to sketch and paint, demonstrating a natural talent that could not be suppressed.

His burgeoning abilities did not go unnoticed. A crucial turning point came with the support and patronage of Henry Phipps, the 1st Earl of Mulgrave. Lord Mulgrave, a connoisseur of the arts, recognized Jackson's potential and provided him with the encouragement and financial means to pursue his artistic ambitions. Another significant early patron was Sir George Beaumont, 7th Baronet, a prominent art patron and amateur painter himself, who also played a role in fostering Jackson's talent. It was through such influential backing that Jackson was able to leave his apprenticeship and dedicate himself fully to art.

Around 1797, Jackson moved to London, the vibrant heart of the British art world. This relocation was pivotal, offering him exposure to a wider range of artistic influences and opportunities for formal study. He is said to have been introduced to the Royal Academy Schools, where he would have had the chance to study from antique casts, live models, and the works of established masters. This period of study was essential in refining his raw talent and equipping him with the technical skills necessary for a successful career in the competitive London art scene.

Rise to Prominence and the Royal Academy

John Jackson's dedication and talent began to yield results. By 1807, he had firmly established himself as a professional portrait painter in London. His early works, often in watercolour, showcased a delicate touch and an ability to capture a sitter's likeness with sensitivity. He gradually transitioned to oil painting, a medium that allowed for greater depth, richness of colour, and textural variety, which became hallmarks of his mature style.

His growing reputation led to his engagement with the Royal Academy of Arts, the preeminent artistic institution in Britain. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1815 (some sources state 1816, but the former is more commonly cited). This was a significant recognition of his standing within the artistic community. Just two years later, in 1817 (or 1818 according to some records), he achieved the distinction of being elected a full Royal Academician (RA), a testament to his established success and the high regard in which his peers held him. Membership in the Royal Academy not only conferred prestige but also provided opportunities to exhibit works regularly at the Academy's influential annual exhibitions.

Jackson's portraits were sought after by a distinguished clientele, including members of the aristocracy, prominent societal figures, fellow artists, and intellectuals. He developed a reputation for producing strong, characterful likenesses, often imbuing his subjects with a sense of dignity and presence. His approach was generally direct and unpretentious, focusing on the sitter's personality rather than excessive flattery or elaborate settings, a quality that set him apart from some of the more flamboyant portraitists of the era.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Techniques

John Jackson's artistic style is rooted in the British portrait tradition, yet it possesses distinct characteristics that define his contribution. He was particularly admired for his robust and truthful portrayal of his sitters, emphasizing their individual character and psychological depth over superficial elegance. This commitment to realism did not preclude a sophisticated handling of paint and a keen eye for colour. Indeed, his colouring was often noted for its richness and harmony, sometimes drawing comparisons to the Venetian masters.

A significant influence on Jackson's development was the work of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy. Like many artists of his generation, Jackson studied and, at times, emulated Reynolds's grand manner and his ability to convey status and personality. However, Jackson forged his own path, often favouring a more direct and less idealized approach than Reynolds. His brushwork could be both fluid and precise, capable of rendering the texture of fabrics, the gleam of an eye, or the subtle contours of a face with equal skill.

The year 1819 marked a pivotal moment in Jackson's artistic journey when he travelled to Italy. He accompanied the renowned sculptor Sir Francis Chantrey, a close friend, on a tour that included Rome, Florence, and Venice. This immersion in the heartland of Renaissance and Baroque art had a profound impact on Jackson. He meticulously studied the works of the Italian Old Masters, particularly Titian, whose mastery of colour and profound humanism deeply resonated with him. This experience visibly enriched Jackson's palette and may have contributed to a greater breadth and confidence in his subsequent work. While in Rome, he was elected a member of the Academy of St. Luke, a prestigious Roman artistic institution.

Jackson's technical skill was considerable. He was adept at capturing the play of light and shadow, using it to model form and enhance the three-dimensionality of his figures. His compositions were generally straightforward but effective, focusing attention on the sitter. He was also a capable draughtsman, and his preparatory sketches, though less known, would have formed an essential part of his working process. He was known for his ability to work relatively quickly, capturing a likeness with an assurance that came from years of practice and keen observation.

Representative Works

Throughout his career, John Jackson produced a substantial body of work, with many portraits that stand as testaments to his skill. One of his most celebrated paintings is the Portrait of Antonio Canova (1819). Canova, the leading Neoclassical sculptor of the age, was an international celebrity, and Jackson painted him during his visit to Rome. The portrait, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1820, was met with considerable acclaim. It depicts Canova with a thoughtful, intense expression, capturing the sculptor's creative energy and intellectual power. The work is notable for its strong characterization and rich, yet sober, palette, reflecting the influence of his Italian sojourn.

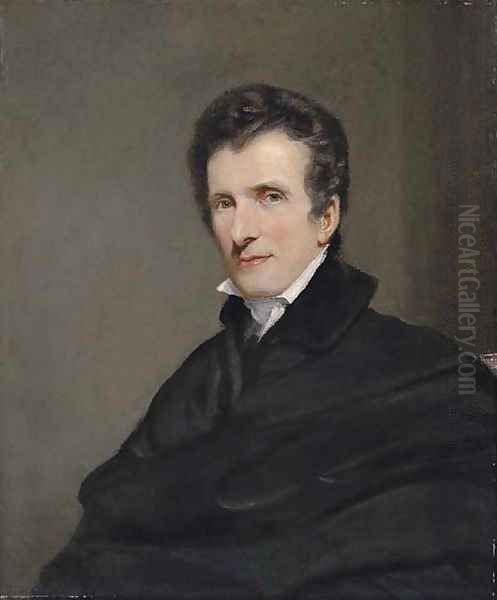

Another important work is his Self-Portrait, of which several versions exist. These self-portraits offer a glimpse into how the artist saw himself – typically as a serious, observant individual. They are often characterized by a direct gaze and a lack of affectation, consistent with his general approach to portraiture.

Jackson painted many of the notable figures of his time. His sitters included the Duke of Wellington, though perhaps less famously than Sir Thomas Lawrence's depictions. He also painted portraits of fellow artists, such as Sir David Wilkie, the celebrated Scottish genre painter, and his travel companion Sir Francis Chantrey. These portraits of artistic peers often possess a particular intimacy and understanding.

Other notable portraits include that of George Dance the Younger, the architect, and an Unfinished Portrait of Mrs. Thynne, which, even in its incomplete state, reveals his confident handling of paint and ability to capture a likeness. He also painted religious figures, such as the Methodist leader John Wesley, a commission that reflected Jackson's own Methodist sympathies. His portrait of the scientist Dr. Wollaston is another fine example of his ability to convey intellect and personality.

His works are held in numerous public collections, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, the British Museum, the Royal Academy of Arts, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Peterhouse, Cambridge, and Brasenose College, Oxford, also hold examples of his portraiture, often of former members or benefactors of these institutions. The Royal College of Physicians in London also has works by him.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

John Jackson worked during a vibrant period in British art, alongside a constellation of talented painters. The dominant figure in portraiture during much of Jackson's career was Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830). Lawrence, who succeeded Benjamin West as President of the Royal Academy in 1820, was renowned for his dazzling technique and glamorous depictions of the elite. While Jackson admired Lawrence, his own style was generally more restrained and less overtly virtuosic, focusing more on solid characterization than on Lawrence's often brilliant, but sometimes superficial, elegance.

Other notable contemporary portraitists included Sir William Beechey (1753-1839), who enjoyed royal patronage and was known for his competent and agreeable likenesses. James Northcote (1746-1831), a pupil of Reynolds, was another established figure, known for his portraits and historical paintings, as well as his sometimes acerbic personality. John Opie (1761-1807), though his career overlapped with Jackson's earlier years, was influential for his direct, unvarnished style, which resonated with a desire for greater naturalism.

Thomas Phillips (1770-1845) was another successful portrait painter and a fellow Royal Academician, known for his reliable likenesses of many prominent figures. Martin Archer Shee (1769-1850), who would succeed Lawrence as President of the Royal Academy, was also a contemporary, though his artistic output is perhaps less celebrated today than his administrative role.

Beyond portraiture, Jackson's contemporaries included masters in other genres. Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841), whom Jackson painted, revolutionized genre painting with his lively and detailed scenes of Scottish life. William Etty (1787-1849), a fellow Yorkshireman and student of Lawrence, became famous, and sometimes controversial, for his sensuous depictions of the nude and historical subjects, often drawing inspiration from Venetian colourists like Titian, an artist Jackson also revered.

J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837) were transforming landscape painting during this period, though their artistic concerns were quite different from Jackson's focus on the human figure. Nevertheless, they were all part of the same artistic ecosystem, exhibiting at the Royal Academy and contributing to the richness of British art in the early 19th century. The Scottish portraitist Sir Henry Raeburn (1756-1823), working primarily in Edinburgh, offered a distinctively robust and insightful style of portraiture that paralleled some of Jackson's own strengths in capturing character. George Romney (1734-1802) and John Hoppner (1758-1810) were prominent portraitists whose careers were ending or had ended as Jackson's was ascending, but their influence was still felt in the London art world.

The Royal Academy exhibitions were central to an artist's career, providing a public platform and a marketplace for their work. Patronage, whether from the aristocracy, the burgeoning middle class, or institutions, was crucial for survival and success. Jackson navigated this world effectively, securing a steady stream of commissions and maintaining a respected position among his peers.

Later Career, Character, and Legacy

John Jackson continued to be a prolific and sought-after portrait painter throughout the 1820s. His style remained consistent, characterized by its honesty, strong drawing, and rich, harmonious colouring. He was known for his amiable character and was well-liked within artistic circles. His Methodist faith was an important aspect of his life, and it is said to have informed his straightforward and unpretentious nature.

Despite his success, Jackson's personal life saw its share of difficulties. He was married twice; his first wife, Maria Fletcher, died in 1817, and he later married Matilda Ward, the daughter of the painter James Ward and niece of George Morland. These personal experiences undoubtedly shaped him, though they are not overtly reflected in his professional artistic output, which maintained a consistent quality.

John Jackson died relatively young, at the age of 53, on 1 June 1831, in St John's Wood, London. His death was lamented by his colleagues and friends in the art world. He left behind a significant body of work that documents many of the leading personalities of his era.

In the annals of British art history, John Jackson is perhaps not as widely known to the general public as Sir Thomas Lawrence or Sir Joshua Reynolds. However, among art historians and connoisseurs of British portraiture, he is recognized as a painter of considerable talent and integrity. His work provides a valuable counterpoint to the more flamboyant styles of some of his contemporaries, offering a more grounded and often more psychologically penetrating view of his sitters.

His commitment to capturing the essential character of an individual, combined with his technical skill and rich use of colour, ensures his place as a distinguished master of the British school of portraiture. His paintings continue to be valued for their artistic merit and as historical documents, offering vivid likenesses of the men and women who shaped Britain in the early 19th century. His influence can be seen in the continuation of a strong, realistic tradition in British portraiture that valued character and substance.

Conclusion

John Jackson RA was an artist who, through talent, perseverance, and the support of discerning patrons, rose from provincial obscurity to become one of Britain's respected portrait painters. His journey from a tailor's apprentice in Yorkshire to a Royal Academician in London is a testament to his dedication. His artistic legacy is defined by portraits that are at once strong, sensitive, and deeply human. Influenced by the great traditions of European art, particularly the Venetian school and the legacy of Reynolds, he nevertheless forged a distinctive style characterized by its truthfulness, robust modelling, and rich colour. While the dazzling brilliance of some contemporaries may have captured more immediate public attention, John Jackson's enduring contribution lies in the quiet power and integrity of his art, offering a profound and lasting insight into the faces and personalities of his age.