John James Audubon remains one of the most celebrated and complex figures in American art and natural history. Born in 1785 and passing away in 1851, he dedicated his life to an ambitious, almost obsessive, quest: to document the avian life of North America in a way never before attempted. His monumental work, The Birds of America, stands as a towering achievement, a fusion of artistic brilliance and scientific observation that captured the dynamism and beauty of the continent's wildlife. Yet, Audubon's legacy is not without its shadows, encompassing controversial methods and personal views that reflect the turbulent era in which he lived. This exploration delves into the life, work, style, and enduring impact of a man often called the "American Woodsman."

Early Life and Formative Years

John James Audubon's story begins not in America, but in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, now Haiti. He was born Jean Rabin on April 26, 1785, in Les Cayes, the illegitimate son of Jean Audubon, a French naval officer and plantation owner, and his Creole mistress, Jeanne Rabine, a chambermaid. His mother died when he was just a few months old. To shield him from the dangers of the Haitian Revolution and the stigma of his birth, his father took him and a half-sister (also illegitimate) to Nantes, France.

In France, Jean Rabin was formally adopted by Jean Audubon and his wife, Anne Moynet Audubon, in 1794, and renamed Jean-Jacques Fougère Audubon. He received a comfortable upbringing, developing an early fascination with the natural world, particularly birds. He enjoyed drawing, music, and dancing, though he was reportedly a restless student in formal settings. His father hoped he would pursue a naval career, but the young Audubon's passion lay elsewhere – in the forests and fields, observing and sketching wildlife.

A pivotal moment came in 1803. To avoid conscription into Napoleon Bonaparte's army and perhaps to manage lead mining interests on a family property, the 18-year-old Audubon was sent to the United States. He arrived in Pennsylvania and moved to the family farm at Mill Grove, near Philadelphia. It was here that he truly began to immerse himself in the American landscape and anglicized his name to John James Audubon. Mill Grove offered abundant opportunities to study local birdlife, and he began conducting the first known bird-banding experiments in North America, tying threads to the legs of Eastern Phoebes to see if they returned to the same nesting spots each year.

Forging a Path: Business Failures and Artistic Calling

Audubon's early years in America were marked by attempts to establish himself in business, endeavors that consistently met with failure. He initially managed the Mill Grove farm, but his interests clearly lay more in ornithology than agriculture or mining. It was during this time, in 1808, that he married Lucy Bakewell, the daughter of a neighboring English farmer. Lucy would prove to be an unwavering source of support throughout his tumultuous life, both emotionally and financially.

Seeking better business prospects, Audubon and Lucy moved west to Kentucky, first to Louisville and then to Henderson. He partnered with Ferdinand Rozier to open a general store. Later, he attempted various ventures, including operating a gristmill and sawmill. However, Audubon's heart wasn't in commerce; his passion for observing and drawing birds often took precedence over managing his businesses. He spent countless hours roaming the Kentucky wilderness, sketching the abundant wildlife.

These business ventures ultimately failed, culminating in bankruptcy in 1819. Audubon was briefly jailed for debt. This period was devastating but also transformative. Stripped of his commercial ambitions, Audubon made a life-altering decision: he would dedicate himself entirely to his art and his grand project of documenting all the birds of North America. Lucy, demonstrating remarkable resilience, supported the family by working as a governess and teacher, enabling her husband to pursue his artistic dream.

The American Wilderness: Travels and Observations

Freed from the constraints of business, Audubon embarked on extensive travels that would define the next two decades of his life. His goal was immense: to find, observe, and draw every bird species native to North America, depicting them life-size in their natural habitats. This required traversing vast, often untamed, territories. He journeyed down the Mississippi River on a flatboat, explored the swamps and forests of Louisiana and Florida, ventured up the Atlantic coast to Labrador, and later traveled the Missouri River into the northern Great Plains.

His methods were direct and characteristic of the era, though controversial by modern standards. To capture the precise details and dynamic poses he sought, Audubon shot the birds, often in large numbers. He then used wires and pins to arrange the specimens into lifelike positions, meticulously drawing them before the colors faded or decomposition set in. While his aim was scientific accuracy and artistic vitality, the sheer scale of his hunting – he estimated killing thousands of birds – draws criticism today.

During his travels, Audubon encountered other naturalists, including Alexander Wilson, a Scottish-American poet, ornithologist, and illustrator who was already working on his own multi-volume American Ornithology. Their meeting was reportedly tense, highlighting the competitive nature of natural history exploration at the time. Wilson's work, while pioneering, often depicted birds in stiffer, more static poses compared to the dynamism Audubon aimed for. Audubon's ambition was to surpass all previous efforts in scope, accuracy, and artistic merit.

Creating a Masterpiece: The Birds of America

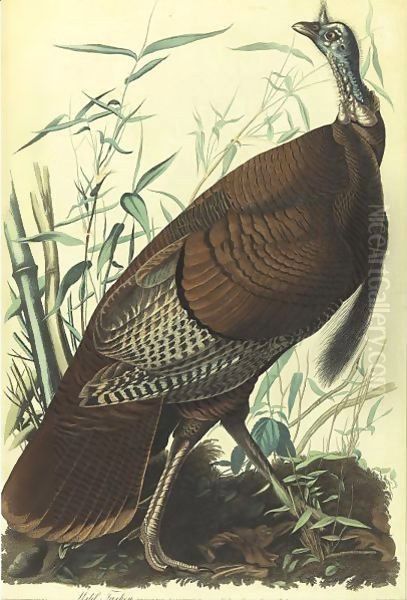

The culmination of Audubon's relentless fieldwork and artistic labor was The Birds of America. Unable to find an American publisher willing to undertake such an ambitious and expensive project, Audubon sailed to Great Britain in 1826, carrying his portfolio of stunning watercolor drawings. In Liverpool, Edinburgh, and London, his work caused a sensation. His rugged "American Woodsman" persona, combined with the undeniable quality of his art, captivated audiences.

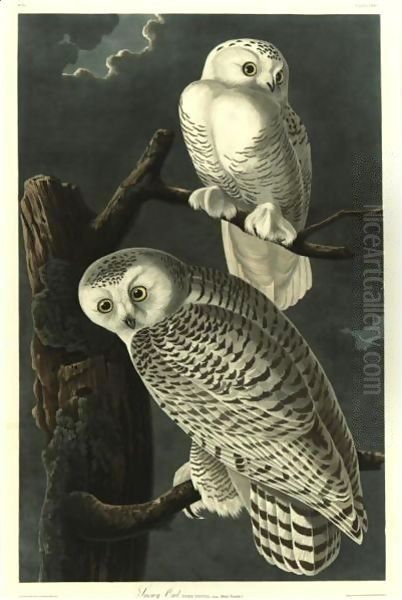

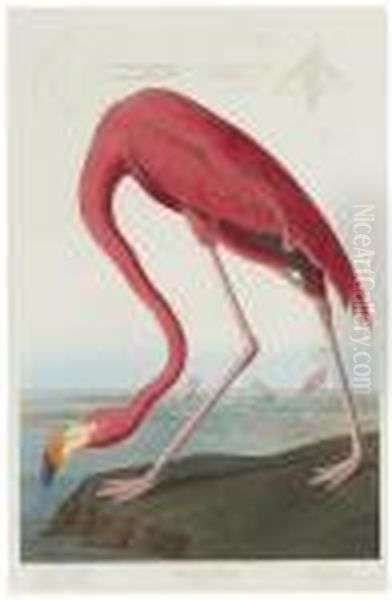

He initially engaged the Edinburgh engraver W. H. Lizars, but after completing the first few plates, Lizars' colorists went on strike. Audubon then found the renowned London engraver Robert Havell Jr. (later assisted by his son, Robert Havell III). This partnership proved crucial. The Havells perfected the use of aquatint engraving, etching, and hand-coloring to translate Audubon's vibrant watercolors into prints of extraordinary detail and beauty.

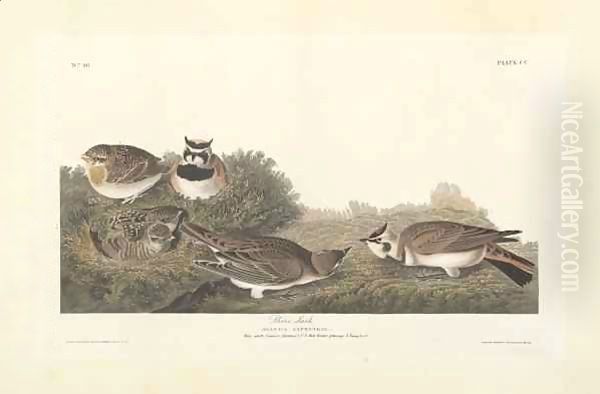

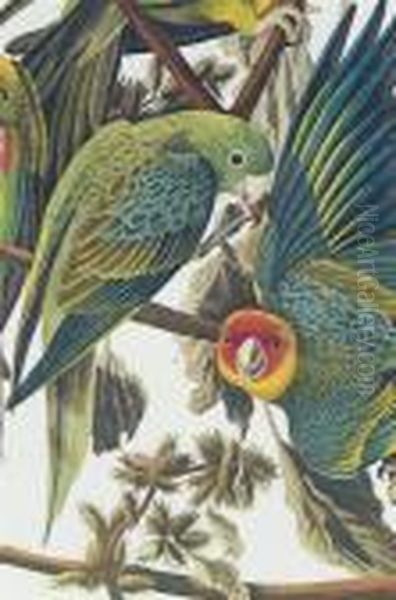

The Birds of America was published serially between 1827 and 1838. It was a colossal undertaking, consisting of 435 plates depicting 1,065 individual birds representing nearly 500 species. Each plate was printed on the largest handmade paper available, known as "Double Elephant Folio" (approximately 39.5 x 26.5 inches), allowing Audubon to depict even the largest birds life-size. Subscribers received installments of five plates at a time. The finished work was typically bound into four massive volumes.

Audubon often focused solely on the birds themselves, relying on assistants for the detailed botanical and landscape backgrounds. Early on, the young Joseph Mason traveled with him and painted many intricate plant settings, though he often received little credit. Later, Maria Martin (who became the second wife of Audubon's collaborator, Reverend John Bachman) contributed significantly, painting exquisite floral and insect details for both The Birds of America and his later work on mammals. Audubon's work built upon, yet dramatically surpassed, earlier efforts by naturalists like Mark Catesby, whose 18th-century Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands was a landmark, and George Edwards, another influential British ornithologist and artist.

European Sojourn and Recognition

Audubon spent significant time in Britain and Europe between 1826 and 1839, overseeing the production of The Birds of America and tirelessly soliciting subscriptions to fund the enormously expensive project. He courted potential patrons among the aristocracy, scientific societies, and wealthy merchants. His striking artwork and charismatic personality earned him entry into esteemed circles.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London and the Linnean Society, significant honors for a largely self-taught naturalist. King George IV was among his subscribers. Despite these successes, financing the publication was a constant struggle. The complete set cost subscribers around $1,000 at the time – an immense sum, equivalent to a substantial fortune today. Fewer than 200 complete sets are thought to have been produced, making The Birds of America one of the rarest and most valuable books in the world. Original sets now command millions of dollars at auction.

While abroad, Audubon also worked on the companion text for his great work, the Ornithological Biography. This five-volume text, written largely in collaboration with the Scottish ornithologist William MacGillivray, provided detailed descriptions of the birds' habits, distribution, and anatomy, along with adventurous narratives drawn from Audubon's journals, known as "Episodes."

Artistic Style and Technique

Audubon's artistic style was revolutionary for its time, breaking from the static, profile views common in earlier ornithological illustration. His key characteristics include:

Dynamism and Drama: He depicted birds in active, often dramatic poses – hunting, feeding, flying, nesting, interacting with each other or their environment. This brought an unprecedented sense of life and narrative to natural history art.

Scientific Accuracy: Despite the artistic flair, Audubon strove for accuracy in plumage detail, scale, and anatomical structure. His close observation and drawing directly from specimens contributed to this precision.

Life-Size Depiction: The massive Double Elephant Folio format allowed him to portray almost all birds at their natural size, enhancing their impact and scientific utility.

Composite Method: He often created compositions by drawing multiple birds (sometimes from different studies) onto a single sheet, arranging them to fit the page while conveying behavioral interactions.

Mixed Media: His original works were primarily watercolor, but he often incorporated pastel, gouache, graphite, and even oil paint to achieve specific textures and effects, particularly for iridescence or soft feathering.

Integration with Habitat: While relying on assistants for many backgrounds, Audubon ensured the settings were appropriate, depicting birds within recognizable landscapes or interacting with specific plants and insects, adding ecological context.

His work stands in contrast to the more rigid, taxonomic approach of predecessors like Alexander Wilson. While Wilson's contribution was immense, Audubon brought a Romantic sensibility and artistic ambition that elevated bird illustration to fine art. His focus on the wildness and beauty of nature resonated with the contemporary Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, who were similarly celebrating the American landscape, albeit through grand vistas rather than detailed wildlife studies. Audubon also produced portraits throughout his career, particularly early on to earn money, showing a competence comparable to established American portraitists like Thomas Sully. There are claims he briefly studied with the Neoclassical master Jacques-Louis David in France, but evidence for this is inconclusive.

The translation of his vibrant originals into prints was masterfully handled by Robert Havell Jr. The aquatint process allowed for fine tonal gradations, essential for rendering feathers and form, while meticulous hand-coloring by a team of artisans ensured the prints captured the brilliance of Audubon's palette.

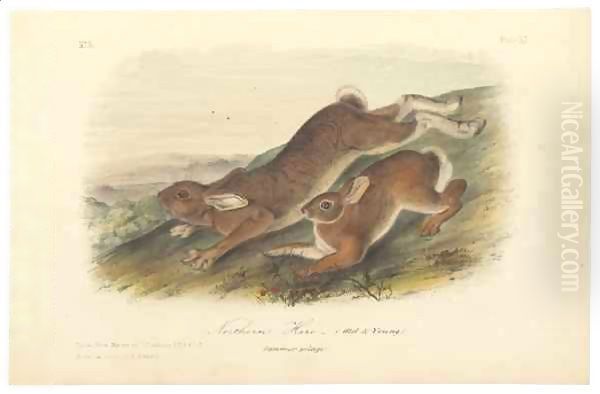

Beyond Birds: The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

Following the completion of The Birds of America, Audubon embarked on another ambitious project: a comprehensive survey of North American mammals. The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America was conceived as a companion work. By this time, Audubon was aging, and his eyesight was beginning to fail. Much of the fieldwork and painting for this project was undertaken by his sons, Victor Gifford Audubon and John Woodhouse Audubon.

Victor handled business aspects and painted some backgrounds, while John Woodhouse became a skilled animal painter in his own right, responsible for about half of the original illustrations. Audubon collaborated closely with his friend, the Reverend John Bachman of Charleston, South Carolina, a respected naturalist who provided much of the scientific text and expertise.

Published between 1845 and 1848 (plates) with text volumes following, the Quadrupeds featured 150 folio plates produced using stone lithography, a newer printing technique that allowed for softer textures suitable for depicting fur. While a significant achievement and scientifically valuable, the Quadrupeds never quite achieved the iconic status or astronomical value of The Birds of America. It nonetheless solidified the Audubon family's contribution to American natural history illustration.

Personal Life and Family

John James Audubon's dedication to his art came at a significant personal cost, particularly to his family life. His long absences during his extensive travels placed immense strain on his wife, Lucy Bakewell Audubon. She endured financial hardship, raised their children largely alone for extended periods, and faced uncertainty about her husband's success and even his safety in the wilderness. Her work as a teacher was crucial for the family's survival during lean years.

They had four children, but two daughters died in infancy. Their two sons, Victor Gifford (1809-1860) and John Woodhouse (1812-1862), became integral parts of the Audubon enterprise. Victor managed the business side, overseeing publications and finances, while John Woodhouse developed considerable artistic talent, assisting his father and taking the lead on the Quadrupeds project. Both sons worked tirelessly to promote and preserve their father's legacy after his death.

Despite the challenges, the marriage between John and Lucy endured for over four decades. Lucy's steadfast support was arguably indispensable to Audubon's ultimate success. She managed his affairs, corresponded with subscribers, and provided stability amidst his often-chaotic pursuit of his vision.

Complexities and Controversies

While celebrated for his artistic and scientific contributions, Audubon's life and methods are viewed through a more critical lens today. Several aspects of his legacy are subjects of ongoing debate:

Hunting Practices: His method of shooting vast numbers of birds to use as models is deeply troubling to modern sensibilities focused on conservation. While specimen collection was standard scientific practice at the time, the scale of Audubon's hunting was exceptional.

Slave Ownership and Racial Views: Audubon owned enslaved people at various points in his life, particularly during his time in Kentucky. He also expressed views critical of the abolitionist movement and held racial prejudices common in the 19th century. This aspect of his life starkly contrasts with the reverence for nature often associated with his name and complicates his status as an environmental icon. His views stand in contrast to the pioneering work of figures like Maria Sibylla Merian, an earlier female naturalist and artist who documented insects and plants in Surinam with remarkable sensitivity, albeit within a colonial context herself.

Scientific Accuracy and Embellishment: While generally accurate, Audubon occasionally embellished his depictions for dramatic effect. He sometimes composed scenes with multiple species that might not naturally interact, or depicted behaviors based on anecdotal accounts rather than direct observation. He also described (and painted) a few "mystery birds" that have never been definitively identified, leading to speculation about errors or even fabrication.

Crediting Collaborators: Audubon relied heavily on assistants like Joseph Mason and Maria Martin for the intricate botanical and landscape backgrounds in his plates, yet they often received minimal or no public credit during his lifetime. Their contributions have only been fully recognized through later scholarship.

These complexities challenge the heroic narrative often presented and force a more nuanced understanding of Audubon as a man of his time, brilliant and driven, yet also flawed and entangled in the problematic social structures of his era.

Later Years and Death

After completing his major publications, Audubon sought a more settled life. In 1842, he purchased an estate in upper Manhattan, New York City, overlooking the Hudson River, which he named "Minnie's Land" after the affectionate nickname he and Lucy used for each other ("Minnie" was also used for their granddaughters). Here, surrounded by family, he spent his final years.

However, his health began to decline rapidly. By the late 1840s, he showed signs of significant cognitive decline, possibly Alzheimer's disease or vascular dementia. His eyesight failed, and his memory faded. His sons, Victor and John Woodhouse, took over the family business, managing reprints of his works and completing the Quadrupeds project.

John James Audubon died at Minnie's Land on January 27, 1851, at the age of 65. He was buried in the Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum in Washington Heights, Manhattan, not far from his estate.

Enduring Legacy and Memorialization

John James Audubon's legacy is immense and multifaceted. He transformed natural history illustration, infusing it with unprecedented artistry, dynamism, and drama. The Birds of America remains a landmark achievement in art, science, and publishing history. His work profoundly influenced subsequent wildlife artists and played a crucial role in fostering public appreciation for North American birds.

His name is famously associated with conservation through the National Audubon Society, founded in 1905 (long after his death) and named in his honor to capitalize on his fame and association with birds. Numerous local chapters, sanctuaries, and nature centers across the United States also bear his name. However, given the increased awareness of his problematic views and actions regarding race and slavery, the appropriateness of the Audubon name for conservation organizations has become a subject of intense debate in recent years, with some chapters opting for name changes.

Museums and institutions worldwide treasure original copies of The Birds of America and The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America. Significant collections of his original watercolor paintings are held by the New-York Historical Society. The John James Audubon Center at Mill Grove in Pennsylvania preserves his first American home and serves as a museum and educational center. The John James Audubon State Park Museum in Henderson, Kentucky, commemorates his time living and working there. His art continues to be celebrated in exhibitions and studied by art historians and ornithologists alike.

Conclusion

John James Audubon was a figure of extraordinary talent, ambition, and contradiction. His life was a relentless pursuit of a singular vision: to capture the entirety of American avian life on paper with unparalleled artistry and scientific fidelity. The Birds of America is the monumental result of that quest, a work that continues to inspire awe with its beauty, scale, and vitality. He bridged the gap between art and science in a way few had before, leaving an indelible mark on ornithology, illustration, and the burgeoning American identity tied to its wilderness.

Yet, his legacy is also interwoven with the troubling realities of his time – the accepted practice of large-scale specimen collection, the pervasive institution of slavery, and prevailing racial prejudices. Acknowledging these complexities does not diminish his artistic achievement but provides a fuller, more honest understanding of the man and his era. Audubon remains a pivotal figure, embodying both the soaring aspirations and the grounded, often uncomfortable, truths of 19th-century America. His work endures, inviting us to marvel at the natural world while prompting critical reflection on how we remember and honor the past.