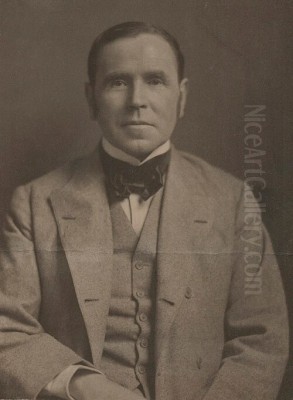

Sir John Lavery stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century art, an Irish painter whose career bridged the worlds of academic tradition, Impressionistic light, and the tumultuous events of his time. Born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, on March 20, 1856, his life journey took him from humble beginnings to the heart of British and European society, establishing him as one of the most sought-after portrait painters of his era. His work provides a fascinating window into the Edwardian social scene, the solemnity of war, and the birth pangs of modern Ireland. Lavery died on January 10, 1941, in Kilkenny, Ireland, leaving behind a rich legacy captured in canvases that continue to resonate with historical and artistic significance.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Lavery's early life was marked by hardship. Orphaned at a young age after his father drowned and his mother died shortly after, he was sent to live with relatives in Scotland. His initial foray into the world of art was practical rather than purely aesthetic; he was apprenticed to a photographer in Glasgow, where he learned the skill of retouching and tinting photographs. This early exposure to capturing likenesses perhaps laid a foundation for his later success in portraiture. However, his ambition lay in painting.

Determined to pursue formal art education, Lavery enrolled at the Haldane Academy in Glasgow during the 1870s. His studies continued, albeit intermittently due to financial constraints. A pivotal moment came when a fire destroyed his studio, but the insurance payout, paradoxically, provided him with the funds to further his studies more seriously. He travelled to London and later, crucially, to Paris in the early 1880s.

In Paris, Lavery enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a hub for international artists seeking alternatives to the rigid École des Beaux-Arts. There, he studied under masters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. Perhaps more importantly, he absorbed the influences swirling through the Parisian art scene, particularly the lingering impact of Realism, exemplified by artists like Gustave Courbet, and the burgeoning influence of Impressionism. He spent time at the Grez-sur-Loing artists' colony, painting en plein air alongside other artists, honing his ability to capture natural light and atmosphere, a skill that would become characteristic of his work. Figures like Jules Bastien-Lepage, known for his blend of academic finish and naturalistic observation, were particularly influential during this period.

The Glasgow School and Rise to Prominence

Upon returning to Glasgow in the mid-1880s, Lavery became associated with the 'Glasgow Boys', a group of radical young painters challenging the established norms of the Scottish art scene. This group, which included artists like James Guthrie, George Henry, and E. A. Walton, favoured realism, tonal harmony, and expressive brushwork, often drawing inspiration from French naturalism and the works of James McNeill Whistler. Lavery, with his Parisian training and developing style, was a natural fit.

His breakthrough came with the painting A Tennis Party (1885). Exhibited widely, this work captured the leisurely elegance of middle-class life with a fresh, modern sensibility, showcasing his growing mastery of light, colour, and composition. It signalled his arrival as a significant talent. His reputation was further cemented by a prestigious commission in 1888: to paint the state visit of Queen Victoria to the Glasgow International Exhibition. This large-scale, complex work, depicting numerous dignitaries, was a resounding success, bringing him national recognition and opening doors to lucrative portrait commissions.

The success of the Queen Victoria painting marked a turning point. Lavery increasingly focused on portraiture, finding a ready market among the wealthy and influential. He moved to London in the 1890s, establishing a studio in Cromwell Place, South Kensington, which quickly became a fashionable gathering spot. London offered a larger stage and access to the upper echelons of society, whose patronage would define much of his subsequent career.

Master of Portraiture

Lavery excelled as a portrait painter. His style was elegant and sophisticated, capturing not just a physical likeness but also a sense of the sitter's personality and social standing. He possessed a fluid brushwork technique, often employing a relatively muted palette but enlivened with subtle tonal variations and occasional flashes of brighter colour. He avoided the stiff formality of much Victorian portraiture, opting instead for more relaxed poses and settings, often imbued with a sense of intimacy or quiet contemplation.

He painted numerous prominent figures of the day, including politicians, aristocrats, artists, and writers. His sitters included Winston Churchill (whom he painted numerous times and who also became a friend and painting companion), members of the Royal Family, George Bernard Shaw, and many leading figures in society. His ability to flatter without sacrificing character made him highly sought after. Works like Father and Daughter (1898), depicting Lavery with his daughter Eileen, showcase his ability to handle more intimate subjects with sensitivity and warmth. This particular piece, along with Spring (1904), found acclaim internationally and was acquired by the Musée du Luxembourg (later transferred to the Louvre), signifying his acceptance within the French art establishment.

His approach was often compared to that of his contemporary, John Singer Sargent, another master portraitist who dominated the London scene. While Sargent was perhaps known for a more dazzling, bravura technique, Lavery offered a quieter, often more introspective elegance. Both artists, however, masterfully captured the essence of the Edwardian era's elite. Lavery's connection and friendship with James McNeill Whistler were also profoundly influential. He admired Whistler's aestheticism, his emphasis on tonal harmony, and his sophisticated compositions, elements that are often reflected in Lavery's own work, particularly in his use of subtle colour gradations and atmospheric effects.

Impressionist Influences and Beyond Portraiture

While portraiture became his mainstay, Lavery continued to explore other genres, often infused with the Impressionistic sensibilities he had absorbed in France. His time spent painting en plein air remained influential. He travelled frequently, particularly enjoying visits to Tangier, Morocco, which provided inspiration for numerous vibrant canvases filled with exotic light and colour. These works often depicted bustling market scenes, tranquil courtyards, and coastal views, demonstrating a looser brushwork and a brighter palette than typically seen in his formal portraits.

His landscapes and genre scenes, like the early A Tennis Party or later works depicting scenes from his travels or leisure activities like horse racing, show his keen interest in capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light. He shared this interest with French Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, though Lavery's style generally retained a stronger sense of structure and form, never fully dissolving into pure sensation in the way some Impressionist works did. He maintained a connection to the aesthetic principles of artists like Whistler and the tonal concerns of the Glasgow School.

Works like Spring (1904), featuring his wife Hazel in their garden, exemplify this blend. It combines the intimacy of a portrait with the fresh atmosphere of an outdoor scene, rendered with a sensitivity to light and colour that speaks to Impressionist influence while retaining a distinct elegance and compositional control characteristic of Lavery. He also painted interiors, often featuring his wife or daughter in their well-appointed home, capturing the interplay of light within domestic spaces.

The Muse: Hazel Lavery

In 1909, John Lavery married Hazel Martyn Trudeau (née Martyn), a beautiful and talented Irish-American painter from Chicago. Hazel became his most frequent model and muse, appearing in hundreds of his paintings. Her striking looks and fashionable presence made her an ideal subject, embodying the elegance and sophistication that Lavery sought to capture. Paintings like The Artist's Studio (c. 1910-13), showing Hazel reclining elegantly amidst the studio setting, are among his most celebrated works featuring her.

Hazel was a prominent socialite in her own right, known for her beauty and charm. Their home in London became a centre for artistic and political figures. She was not merely a passive model; she was an artist herself and deeply involved in Lavery's world. Her image became incredibly famous in Ireland when, after the establishment of the Irish Free State, Lavery adapted one of his portraits of her, depicting her as the allegorical figure of Kathleen Ni Houlihan, for use on the new Irish banknotes. This image remained on Irish currency for decades, making Hazel Lavery's face one of the most recognizable in the country.

Their marriage, while a source of great inspiration for Lavery's art, also faced challenges. Hazel's social life and reported relationships with other figures, including potentially Michael Collins, added a layer of intrigue and gossip around the couple. Despite any personal complexities, her presence in his work is undeniable, lending a distinct glamour and personality to a significant portion of his oeuvre.

Documenting an Era: War and Politics

The outbreak of the First World War saw Lavery appointed as an official war artist by the British government in 1917. However, ill health, possibly exacerbated by a serious car accident involving a taxi in 1915 and injuries sustained during a Zeppelin raid, prevented him from travelling to the Western Front as intended. Instead, he focused on depicting the war effort closer to home, painting scenes of the Royal Navy at Scapa Flow and Rosyth, airships, munitions factories, and military hospitals. Works like HMS Terror capture the imposing presence of naval power.

His most notable work related to conflict, however, came from a different context. In 1916, he attended the trial of Sir Roger Casement, the Irish nationalist executed for treason by the British government for his activities during the Easter Rising. Lavery captured the intense courtroom drama in his painting High Treason, The Appeal of Sir Roger Casement. This work is a powerful historical document, offering a unique visual record of a pivotal and controversial moment in Anglo-Irish history. It showcases Lavery's skill in handling complex group compositions and capturing the sombre atmosphere of the event.

Lavery's Irish roots and connections meant he was also close to the events surrounding the Irish War of Independence and the subsequent Civil War. His London home, largely through Hazel's connections, became an informal meeting place during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations in 1921. He painted portraits of key Irish leaders, including a poignant posthumous portrait of Michael Collins lying in state after his assassination in 1922. These works underscore Lavery's position as an artist deeply engaged with the historical currents of his time, using his skills to document moments of national significance for both Britain and Ireland. His role contrasts with other official war artists like Paul Nash or C.R.W. Nevinson, who depicted the trenches, or fellow Irishman William Orpen, who also produced powerful war portraits and scenes from the front.

Later Career and International Recognition

Lavery continued to paint prolifically throughout the 1920s and 1930s. He maintained his status as a leading portrait painter, though societal tastes began to shift with the rise of modernism. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy (having been elected an Associate in 1911 and a full Academician in 1921), the Royal Scottish Academy, and internationally. His work was shown in Paris, Rome, Berlin, and Venice, confirming his established reputation across Europe.

He received numerous honours in recognition of his artistic achievements and public standing. He was knighted in 1918, becoming Sir John Lavery. In 1930, he was granted the Freedom of the City of Belfast, a significant honour in his city of birth, and notably, he was the first artist to receive this distinction. Five years later, in 1935, he was awarded the Freedom of the City of Dublin. He also received honorary degrees from the University of Dublin (Trinity College) and Queen's University Belfast, acknowledging his contribution to the arts and his standing in both parts of Ireland.

Despite the changing artistic landscape, Lavery remained committed to his own style, rooted in skilled draughtsmanship, tonal sensitivity, and an elegant aesthetic. He continued to travel, paint landscapes, and accept portrait commissions until late in his life. His later works retain the fluency and confidence developed over a long and successful career.

Artistic Connections and Collaborations

Throughout his career, Lavery moved within prominent artistic circles. His early association with the Glasgow Boys (James Guthrie, E. A. Walton, etc.) was formative. His move to London brought him into contact with the leading figures of the British art establishment. The most significant artistic relationship was arguably with James McNeill Whistler. Lavery deeply admired the American expatriate artist, and Whistler's influence is evident in Lavery's tonal harmonies, compositional arrangements, and sophisticated, often muted palette. They shared a friendship, with Whistler appreciating the younger painter's talent.

Lavery also interacted with other major figures like John Singer Sargent, Walter Sickert, and Philip Wilson Steer, who were shaping the London art scene. He maintained connections with French artists from his time in Paris and Grez-sur-Loing. Patronage was also crucial. His relationship with Sir William Burrell, the wealthy Glasgow shipowner and collector, was significant. Burrell commissioned several works from Lavery, including a portrait of his sister Mary Burrell, which is often cited as one of Lavery's finest portraits, showcasing his ability to combine elegance with psychological depth.

His role as President of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters (from 1932) further cemented his position within the established art world. He was also involved with the Belfast Art Club, serving as its president in 1919. These connections highlight his integration into the artistic infrastructure of Britain and Ireland.

Personal Life: Triumphs and Trials

Lavery's personal life contained both joy and sorrow. His first wife, Kathleen MacDermott, whom he married in 1889, tragically died from tuberculosis just a couple of years later, shortly after the birth of their daughter, Eileen. Eileen Lavery (1890-1935) would herself become a painter, sometimes exhibiting alongside her father. His second marriage to Hazel Martyn in 1909 brought glamour and companionship, but also, as mentioned, its own complexities and public scrutiny. Hazel predeceased him, dying in 1935.

Lavery himself faced significant health challenges, particularly following the accidents during the war years. These incidents reportedly affected his ability to work for periods and may have contributed to his inability to serve as a war artist on the front lines. Despite these setbacks, he remained remarkably productive throughout his long life.

His connection to his birthplace remained strong. In a gesture of generosity and faith, he donated a large triptych altarpiece, The Madonna of the Lakes, to St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Church in Belfast in 1918, dedicating it to the memory of his family and the people of the city. This act reflected his Catholic background and his enduring link to Belfast. He eventually returned to Ireland in his final years, dying at the home of a friend in Kilmaganny, County Kilkenny, in 1941, at the age of 84.

Legacy and Collections

Sir John Lavery's legacy is that of a highly skilled and successful artist who captured the spirit of his age, particularly the elegance of Edwardian society and the significant historical moments he witnessed. While perhaps overshadowed in modernist narratives by more avant-garde figures, his work remains highly regarded for its technical proficiency, aesthetic appeal, and historical value. He successfully navigated the art worlds of Glasgow, London, Paris, and Dublin, achieving international fame.

His paintings are held in major public collections around the world, including the Tate Britain in London, the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, the Ulster Museum in Belfast, the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Imperial War Museums, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (works transferred from the Louvre/Luxembourg), the National Galleries of Scotland, and numerous galleries in the United States, Canada, and Australia. His enduring popularity is also evident in the art market, where his works continue to command significant prices.

He stands as a key figure in both Irish and British art history, an artist whose portraits provide a gallery of the great and the good of his time, and whose broader work reflects the artistic currents, social life, and political upheavals of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His ability to blend academic training with Impressionistic light and a modern sensibility ensured his lasting appeal.

Conclusion

Sir John Lavery's career spanned a remarkable period of change, from the height of Victorianism through the Edwardian era, the trauma of the First World War, and the emergence of modern Ireland. As a painter, he was versatile, excelling in portraiture but also producing compelling landscapes, genre scenes, and historical records. His association with the Glasgow Boys, his admiration for Whistler, and his absorption of French influences shaped a style that was both elegant and observant. Through his art, particularly his society portraits and his documentation of war and political events, Lavery created an invaluable visual chronicle of his time, securing his place as a significant artist whose work continues to engage and inform.