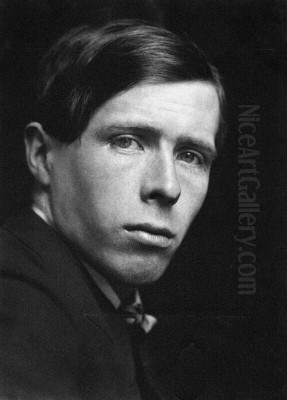

Sir William Newenham Montague Orpen stands as a significant, albeit complex, figure in early 20th-century British and Irish art. Born in Stillorgan, County Dublin, Ireland, on November 27, 1878, and passing away in London on September 29, 1931, Orpen navigated the worlds of Edwardian high society, the horrors of the Western Front, and the shifting cultural landscape of his time. He achieved immense fame as a society portraitist and later as one of the most prolific and impactful official war artists of the First World War. Yet, his career was also marked by controversy and a certain sense of detachment that coloured perceptions of his work. This exploration delves into the life, art, and legacy of a painter whose technical brilliance captured the faces and events of a transformative period in history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

William Orpen hailed from a prosperous Protestant family in Dublin; his father was a solicitor, and the family lineage included notable figures, such as the Victorian-era photographer George Charles Beresford. Showing artistic talent from a young age, Orpen enrolled at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art when he was just thirteen. His precocity was evident, and he quickly absorbed the academic training offered there, developing foundational skills in drawing and painting.

Seeking broader horizons and more advanced training, Orpen moved to London in 1897 to attend the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art. This was a pivotal period in his development. The Slade, under the influential guidance of figures like Henry Tonks, Philip Wilson Steer, and Frederick Brown, emphasized rigorous draughtsmanship and drawing from life, principles that would underpin Orpen's art throughout his career. Tonks, in particular, was a demanding teacher known for his insistence on anatomical accuracy and structural integrity in drawing, leaving a lasting mark on Orpen's approach.

At the Slade, Orpen was part of a brilliant generation of students. He formed a close, sometimes competitive, friendship with Augustus John, another prodigious talent known for his bohemian flair and expressive drawing. Other contemporaries included John's sister Gwen John, Ambrose McEvoy, and Wyndham Lewis, all of whom would go on to make significant contributions to British art. Orpen quickly distinguished himself, winning the Slade's composition prize in 1899 for his ambitious painting The Play Scene from Hamlet. His technical facility was already widely acknowledged among his peers and tutors.

The Ascendant Portraitist

Upon leaving the Slade, Orpen rapidly established himself as a sought-after portrait painter in London. The Edwardian era, with its confidence and prosperity (at least among the elite), provided fertile ground for portraitists. Orpen's style, characterized by assured, fluid brushwork, a keen eye for likeness and character, and often dramatic lighting reminiscent of Old Masters like Rembrandt and Velázquez, appealed greatly to the establishment. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture not just the physical appearance of his sitters but also a sense of their personality and social standing.

His studio became a hub for the great and the good of British society. He painted politicians, aristocrats, artists, writers, and financiers. Notable portraits from this pre-war period include depictions of figures like Winston Churchill and the writer George Bernard Shaw. Orpen's portraits were often more than mere likenesses; they were carefully constructed compositions that conveyed status, intelligence, and sometimes a hint of vulnerability beneath the public facade. He often incorporated mirrors and complex interior settings, adding layers of visual interest and psychological depth, a technique seen in works like The Mirror.

During this time, Orpen also engaged with the contemporary art scene. He exhibited regularly at the New English Art Club (NEAC), a society founded as an alternative to the more conservative Royal Academy, although he would later become a prominent member of the RA himself. His work from this period sometimes shows an awareness of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly the work of Edouard Manet, whom he admired. A work like Homage to Manet (though later facing criticism for other reasons) explicitly acknowledged this influence, placing figures like George Moore, Walter Sickert, and Henry Tonks before Manet's Portrait of Eva Gonzalès. He was, alongside contemporaries like John Singer Sargent and Philip de László, one of the dominant forces in British portraiture.

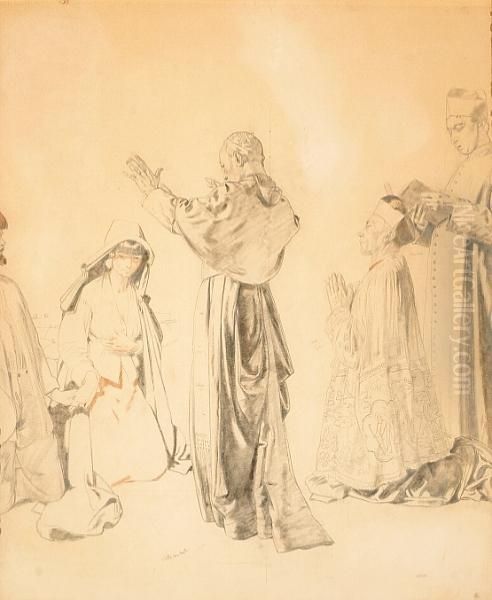

In 1901, Orpen married Grace Knewstub, the daughter of an artist and sister-in-law of fellow artist William Rothenstein. They had three daughters. Orpen also maintained strong ties to Ireland, teaching for a time at his alma mater, the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, and painting subjects related to Irish life and the burgeoning Irish Cultural Revival, such as The Holy Well and Sowing New Seed. These works often depicted rural Irish life with a blend of realism and symbolic allegory, reflecting his engagement with his homeland's identity. He briefly co-founded the Chelsea Art School with Augustus John around 1903, though their differing temperaments and perhaps a casual discussion in a pub led to its quick demise.

Witness to War: The Official Artist

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 profoundly altered Orpen's life and art. Initially too old for active service, he channelled his energy into the war effort through his painting. In 1917, he was appointed an official war artist by the British government's Department of Information, with the honorary rank of Major in the Army Service Corps. He was sent to the Western Front in France, tasked with documenting the war, particularly the personnel of the British Expeditionary Force.

Orpen threw himself into this role with extraordinary energy and productivity. Unlike some war artists who focused primarily on the symbolic or abstracted horrors of war, Orpen often adopted a more direct, observational approach, rooted in his skills as a portraitist and draughtsman. He painted numerous portraits of generals, politicians, and ordinary soldiers, capturing the strain, determination, and exhaustion etched on their faces. Field Marshal Haig, Air Marshal Trenchard, and many others sat for him, often in makeshift studios near the front lines.

Beyond portraiture, Orpen produced a searing body of work depicting the landscapes and aftermath of battle. Paintings like Thiepval (1917) and Zonnebeke (1918) convey the utter desolation of the Somme and Flanders battlefields – landscapes scarred by shell craters, littered with debris, mud-filled trenches, and skeletal trees under ominous skies. He painted scenes inside casualty clearing stations, images of German prisoners of war, and haunting depictions of the dead. His work often highlighted the human cost of the conflict with unflinching realism, though sometimes tempered with an almost surreal beauty in the rendering of light and colour across the devastated terrain.

Orpen's war work was widely exhibited during and immediately after the war, making a powerful impact on the public. He was prolific, ultimately donating a vast collection of 138 paintings and drawings to the British government in 1918, which formed a significant part of the new Imperial War Museum's collection. His contribution was recognized with a knighthood (Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, KBE) in 1918. His direct, often harrowing, depictions offered a stark contrast to the more Vorticist-influenced styles of contemporaries like Wyndham Lewis or C.R.W. Nevinson, or the pastoral melancholy of Paul Nash, providing a crucial, realist perspective on the conflict.

Post-War Fame and Controversy

Following the Armistice, Orpen remained in France as an official artist for the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. He was commissioned to paint three large canvases documenting the historic event. The most famous of these is The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28th June 1919. While technically brilliant, capturing the likenesses of the assembled world leaders (Woodrow Wilson, Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau, etc.) in the opulent setting, the painting was criticized by some for its perceived lack of emotional depth and for dwarfing the statesmen within the grandeur of the Hall of Mirrors, perhaps suggesting their insignificance relative to the historical moment or the setting itself.

Another painting intended for the Peace Conference commission caused significant controversy. Orpen initially painted a scene depicting the conference delegates, but became disillusioned with the proceedings, feeling the politicians were failing the soldiers who had sacrificed so much. He painted out the dignitaries and replaced them with a coffin draped in the Union Flag, guarded by two ghostly, emaciated soldiers, titling it To the Unknown British Soldier in France. This stark, allegorical indictment of the peace process and tribute to the common soldier was rejected by the Imperial War Museum, who had commissioned a historical record, not a personal commentary. The painting caused a public outcry when exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1923. Orpen later painted over the soldiers and coffin, returning it closer to its original state (though still omitting the politicians), and presented it under the title The Unknown British Soldier in France (revised version). The original version, however, remains a powerful testament to his conflicted feelings about the war's aftermath.

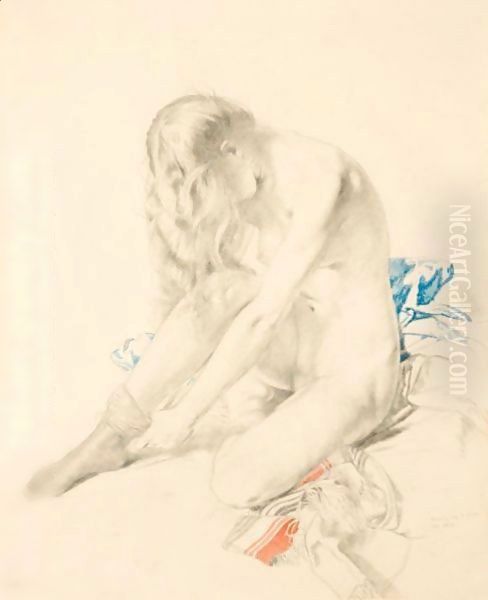

During his time in France, Orpen also formed a close relationship with Yvonne Aupicq, who became his model and mistress. She appears in numerous portraits and studies from this period, often depicted with sensitivity and intimacy. This relationship perhaps reflected Orpen's own sense of being something of an outsider – an Irishman working within the heart of the British establishment, a witness to immense suffering while enjoying relative safety and privilege. His experiences and reflections were later published in his memoir, An Onlooker in France, 1917-1919 (1921), a valuable first-hand account combining text with reproductions of his wartime drawings and paintings.

Artistic Style Revisited

Orpen's artistic style remained remarkably consistent throughout his career, founded on the bedrock of his Slade training. His draughtsmanship was exceptional – fluid, accurate, and expressive. He could capture a likeness with seemingly effortless strokes, whether in quick charcoal sketches or highly finished oil portraits. His handling of paint was confident and often vigorous, using visible brushstrokes but always maintaining control over form and structure.

His use of light was often dramatic, employing chiaroscuro techniques reminiscent of Baroque masters like Rembrandt to model form and create atmosphere. While grounded in realism, his work wasn't photographic. He understood how to manipulate composition, pose, and lighting to convey character and mood. Although aware of modern art movements, he remained largely committed to representational painting. His brief engagement with Impressionist colour and light, particularly influenced by Manet, was integrated into his fundamentally academic framework rather than leading him towards abstraction or radical experimentation like some of his contemporaries.

Compared to the flamboyant bohemianism of Augustus John, Orpen appeared more conventional, yet his work often contained subtle psychological insights. Contrasted with the elegant, sometimes superficial, society portraits of Sargent, Orpen's work could feel more solid, occasionally more probing. He was a master technician, capable of rendering textures – fabric, flesh, metal – with convincing veracity. This technical prowess served him equally well in the formal setting of a state portrait or the grim reality of a battlefield landscape.

Irish Identity and Cultural Connections

Despite spending most of his professional life in London and achieving fame within the British art establishment, Orpen retained a connection to his Irish roots. His early involvement with the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art as a teacher, and his paintings depicting Irish rural life and themes related to the Celtic Revival (The Western Wedding, Sowing New Seed, The Holy Well), demonstrate this engagement. These works stand apart from his society portraits and war paintings, exploring themes of tradition, folklore, and national identity.

His position as a successful Irish artist within the British Empire during a period of intense political turmoil in Ireland (leading up to and following the Easter Rising of 1916 and the War of Independence) was complex. He painted portraits of figures associated with both British administration and Irish cultural nationalism. While not overtly political in the manner of, say, Jack B. Yeats, whose work became increasingly focused on Irish life and independence, Orpen's Irish-themed works contribute to the broader narrative of Irish art in the early 20th century, alongside artists like Yeats, Paul Henry, and Sir John Lavery (another Irish-born artist who found great success in London). Orpen's exploration of Irish identity, often through allegorical or genre scenes, adds another dimension to his multifaceted career.

Later Years and Legacy

In the post-war years, Orpen remained one of Britain's most successful and highly paid portrait painters. He was elected a full member of the Royal Academy (RA) in 1919 (having been an Associate since 1910). He continued to receive prestigious commissions and enjoyed considerable fame and financial success. However, the intensity of his war years seemed to have taken a toll. Some critics felt his later work occasionally lacked the vitality of his earlier portraits, becoming somewhat formulaic.

His health began to decline in the late 1920s. He suffered from alcoholism and possibly the lingering psychological effects of his wartime experiences. Sir William Orpen died relatively young, at the age of 52, in London on September 29, 1931.

Orpen's legacy is substantial. As a portraitist, he created an invaluable record of the leading figures of the Edwardian and wartime eras. His technical mastery remains undeniable. As a war artist, his contribution is immense; his paintings offer some of the most powerful and enduring images of the First World War, capturing both the devastation of the landscape and the humanity of its participants. Works like The Signing of Peace and To the Unknown British Soldier remain important historical documents and points of discussion about the representation of war and peace.

Today, his works are held in major collections worldwide, including the Tate Britain, the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Imperial War Museums, the National Gallery of Ireland, and numerous other institutions. While his reputation may have fluctuated, overshadowed at times by the rise of modernism, recent reappraisals have reaffirmed his significance as a brilliant draughtsman, a perceptive portraitist, and a crucial visual chronicler of the dramatic first decades of the 20th century. He remains a key figure in both British and Irish art history.

Conclusion

Sir William Orpen was an artist of exceptional talent whose career bridged the gap between traditional academic painting and the demands of documenting a modern, industrialized war. From the gilded salons of Edwardian London to the mud-soaked trenches of the Western Front, his brush captured the faces and events of his time with remarkable skill and, often, profound empathy. While his success within the establishment and occasional controversies complicate his narrative, his vast output, particularly his war art and insightful portraits, secures his place as a major artist of the early twentieth century. His work continues to offer compelling insights into the people, power structures, and profound traumas of the era he so meticulously recorded.