Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, known to the world as Donatello, stands as one of the most influential and revolutionary artists of the Italian Renaissance. Born in Florence around 1386, he emerged during a period of profound cultural and intellectual rebirth, and his work would come to define the very essence of Renaissance sculpture. Rejecting the lingering stylizations of the Gothic era, Donatello embraced a powerful naturalism, infused his figures with unprecedented psychological depth, and masterfully revived classical forms, all while pioneering new techniques that expanded the expressive potential of his chosen medium. His long and prolific career, spanning much of the 15th century until his death in Florence in 1466, left an indelible mark not only on his contemporaries but on the entire subsequent history of Western art.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Florence, at the turn of the 15th century, was a vibrant crucible of artistic innovation and humanist thought. It was in this stimulating environment that Donatello received his early training. While details of his earliest education are somewhat scarce, it is widely believed he initially trained as a goldsmith. This background would have provided him with a keen eye for detail and a mastery of metalworking techniques that would prove invaluable in his later bronze sculptures.

A pivotal moment in his development was his association with Lorenzo Ghiberti, a leading sculptor of the time. Donatello worked in Ghiberti's workshop, likely assisting on the monumental bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery, a project that captivated the city. This experience exposed him to the complexities of large-scale bronze casting and the competitive artistic environment of Florence. It was also during this period that he formed a close, albeit sometimes contentious, friendship with Filippo Brunelleschi, the brilliant architect who would later design the dome of Florence Cathedral.

Around 1402-1404, Donatello and Brunelleschi are said to have traveled to Rome together. This journey was transformative. Immersed in the ruins of the ancient Roman Empire, they meticulously studied classical sculptures and architecture. This direct engagement with antiquity profoundly shaped Donatello's artistic vision, instilling in him a deep appreciation for Roman naturalism, emotional expression, and the heroic depiction of the human form. This study of classical precedent would become a cornerstone of his revolutionary approach to sculpture.

The Dawn of a New Era: Early Masterpieces

Upon his return to Florence, Donatello began to receive significant commissions, quickly establishing himself as a formidable talent. His early works for prominent public spaces like the Orsanmichele (the "granary church" and guild hall) and the Florence Cathedral (Duomo) showcased his burgeoning genius and his departure from traditional Gothic aesthetics.

One of his earliest major marble statues for an exterior niche at Orsanmichele was St. Mark (c. 1411-1413), commissioned by the Linen Weavers' Guild. This figure, with its dignified contrapposto stance (a naturalistic pose where the figure’s weight is shifted onto one leg), intense gaze, and realistically rendered drapery, signaled a new direction in sculpture. Donatello designed the figure with an understanding of its placement, elongating the torso and head so it would appear correctly proportioned when viewed from below. This attention to optical effects and the viewer's perspective was a hallmark of his innovative thinking.

Even more striking was his St. George (c. 1415-1417), commissioned by the Armourers' and Sword Makers' Guild for Orsanmichele. This marble statue embodies the Renaissance ideal of the Christian knight, youthful, alert, and resolute. The figure’s subtle tension and psychological preparedness convey a sense of impending action. Perhaps even more revolutionary was the shallow relief carving on the statue's base, depicting St. George and the Dragon. Here, Donatello employed his innovative rilievo schiacciato (flattened or squashed relief) technique. By carving with extreme subtlety and minimal depth, he created a remarkable illusion of atmosphere and deep space, relying on the play of light and shadow to define forms. This was a radical departure from the more deeply cut reliefs common at the time and demonstrated his ability to "paint" with marble.

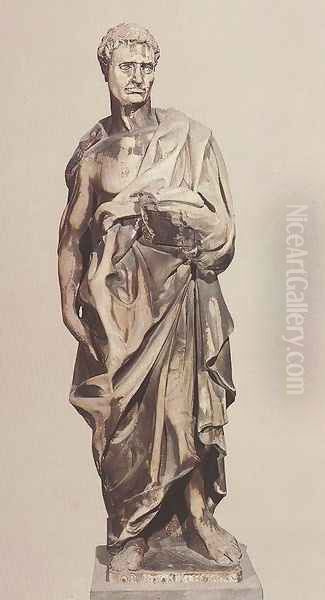

During this period, Donatello also created a series of powerful marble statues of prophets for the niches of the Campanile (bell tower) of Florence Cathedral. Figures like Prophet Jeremiah (c. 1423-1427) and the famously intense Habakkuk (c. 1427-1436), nicknamed "Lo Zuccone" (the pumpkin-head or bald-head) due to its bald pate, are characterized by their stark, unidealized realism and profound psychological depth. These are not serene, otherworldly figures but deeply human individuals, burdened by their divine inspiration and conveying a palpable sense of inner turmoil. Their rugged features and expressive faces were a bold assertion of naturalism.

The Bronze Revolution: David and Beyond

While Donatello excelled in marble, he also became a supreme master of bronze, a medium that allowed for greater dynamism and finer detail. His most iconic bronze work, and arguably one of the most famous sculptures of the Renaissance, is his David (c. 1440s). Commissioned likely by Cosimo de' Medici for the courtyard of the Palazzo Medici, this statue is revolutionary on multiple fronts. It is considered the first freestanding nude male sculpture cast in bronze since antiquity, a bold revival of a classical form.

The youthful David stands in a relaxed contrapposto, his foot resting on the severed head of Goliath. The figure is slender, almost androgynous, and imbued with a quiet, contemplative sensuality that was unprecedented. Unlike earlier depictions of David as a kingly figure or a robust hero, Donatello presents him as an adolescent, whose victory seems almost miraculous, emphasizing divine favor over brute strength. The smooth, polished bronze surface enhances the figure's lifelike quality. The David became a potent symbol of the Florentine Republic's own triumphs against larger, more powerful enemies.

Beyond the David, Donatello created other significant bronze works, such as the enigmatic Attis-Amorino (c. 1440s), a playful and somewhat mischievous figure that blends classical and pagan motifs. His technical proficiency in bronze casting was unparalleled, allowing him to achieve complex compositions and exquisite surface treatments. He understood the material's capacity for both strength and delicacy, pushing its boundaries to new expressive heights.

Innovations in Relief and Perspective

Donatello's mastery of relief sculpture continued to evolve throughout his career. He refined his rilievo schiacciato technique, creating scenes of astonishing spatial complexity and narrative power. A prime example is The Feast of Herod (c. 1423-1427), a bronze relief panel for the baptismal font of the Siena Cathedral. This work is a tour-de-force of early Renaissance perspective. Donatello masterfully employs linear perspective, a system for creating an illusion of depth on a flat surface that his friend Brunelleschi had been developing, to construct a believable architectural space.

In The Feast of Herod, figures recede into the background through a series of arches, creating a palpable sense of depth and drama. The horrified reactions of Herod and his guests to the presentation of John the Baptist's head are vividly portrayed, showcasing Donatello's skill in conveying intense emotion. This work had a profound impact on painters like Masaccio, who were also exploring the new science of perspective in their frescoes. Other notable reliefs, such as the tender Madonna of the Clouds (c. 1425-1435) in marble and the Pazzi Madonna (c. 1422), further demonstrate his ability to create intimate and emotionally resonant scenes within the shallow confines of relief.

The Paduan Period: Monumental Achievements

From 1443 to 1453, Donatello spent a decade in Padua, a significant university city and artistic center in northern Italy. This period was marked by two of his most ambitious and monumental undertakings: the equestrian statue of the condottiero (mercenary captain) Erasmo da Narni, known as Gattamelata, and the sculptural program for the high altar of the Basilica di Sant'Antonio (known as "Il Santo").

The bronze equestrian statue of Gattamelata (c. 1447-1453), erected in the piazza outside the Basilica di Sant'Antonio, was a groundbreaking achievement. It was the first monumental bronze equestrian statue to be cast since antiquity, directly referencing the Roman statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome. Donatello faced immense technical challenges in casting such a large-scale work. The statue portrays Gattamelata with an air of calm command and authority, a powerful image of Renaissance individualism and military prowess. The horse is rendered with remarkable anatomical accuracy and vitality. The Gattamelata set a new standard for equestrian monuments that would be emulated for centuries.

For the high altar of Il Santo, Donatello created a complex ensemble of nearly two dozen bronze sculptures, including seven life-size statues (the Virgin and Child with Saints Francis, Anthony, Justina, Daniel, Louis, and Prosdocimus) and numerous reliefs depicting scenes from the life of St. Anthony and symbols of the Evangelists. Though the original arrangement was later dismantled and controversially reconstructed, the individual figures and reliefs attest to Donatello's extraordinary narrative skill, his ability to differentiate characters, and his mastery in conveying a wide range of emotions, from serene devotion to dramatic intensity. This Paduan period solidified Donatello's reputation throughout Italy.

Later Works and Emotional Intensity

Upon his return to Florence in the 1450s, Donatello's style took on an even greater emotional intensity, sometimes bordering on the raw and unsettling. He seemed less concerned with classical grace and more focused on expressing profound spiritual and psychological states.

A striking example of this late style is the wooden statue of the Penitent Magdalene (c. 1453-1455), created for the Florence Baptistery. This is a far cry from the idealized beauty often associated with the Renaissance. Donatello depicts Mary Magdalene as an emaciated, gaunt figure, her body ravaged by years of ascetic repentance in the desert. Her tangled hair acts as her only garment, and her face is a mask of anguish and spiritual torment. The work's stark realism and raw emotional power are deeply moving and almost shocking in their intensity.

Another significant late work is the bronze group Judith and Holofernes (c. 1457-1464). Originally perhaps intended for a fountain, it was later placed in the Piazza della Signoria as a symbol of civic virtue and the triumph over tyranny, much like his earlier David. The sculpture depicts the biblical heroine Judith in the act of decapitating the Assyrian general Holofernes. The composition is complex and dramatic, capturing the gruesome moment with unflinching realism. Judith's determined expression contrasts with Holofernes's limp, defeated form.

Among his very last works were two bronze pulpits for the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence (c. 1460-1466), which were completed by his assistants after his death. The reliefs on these pulpits, depicting scenes from the Passion of Christ and the life of St. Lawrence, are characterized by a frenetic energy, crowded compositions, and an almost expressionistic distortion of figures, conveying extreme suffering and spiritual turmoil. These late works show Donatello continuing to experiment and push the boundaries of sculptural expression until the very end of his life.

Donatello's Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Innovation

Donatello's artistic style is multifaceted, but several key characteristics define his revolutionary contributions:

Psychological Realism and Emotional Depth: More than any sculptor before him, Donatello imbued his figures with a profound sense of inner life. His saints, prophets, and even mythological figures are not mere symbols but complex individuals, capable of expressing a wide spectrum of human emotions, from quiet contemplation to intense anguish.

Revival and Reinterpretation of Classical Forms: Donatello deeply studied and understood classical art, adopting elements like contrapposto, naturalistic anatomy, and heroic nudity. However, he did not simply copy antiquity; he reinterpreted it through a Christian lens and infused it with a new emotional and spiritual intensity.

Technical Mastery and Material Versatility: Donatello was a master of various materials, including marble, bronze, wood, and terracotta. He understood the unique properties of each and adapted his techniques accordingly. His invention of rilievo schiacciato and his mastery of bronze casting were particularly influential.

Understanding of Perspective and Space: Influenced by the experiments of Brunelleschi and the theories of Leon Battista Alberti, Donatello was among the first sculptors to systematically apply principles of linear perspective in his reliefs, creating convincing illusions of depth and space. He also considered the viewer's vantage point when designing his statues for specific locations.

Individuality of Figures: Each of Donatello's figures possesses a distinct personality. He avoided generic types, instead striving to capture the unique character and psychological state of each individual, whether it be the youthful confidence of St. George, the weary wisdom of "Lo Zuccone," or the tormented spirituality of the Penitent Magdalene.

A Circle of Geniuses: Donatello and His Contemporaries

Donatello did not work in a vacuum. He was part of an extraordinary generation of artists in Florence who collectively forged the Renaissance. His interactions, collaborations, and rivalries with these figures were crucial to his development and to the artistic ferment of the era.

His lifelong relationship with Filippo Brunelleschi was particularly significant. Their early trip to Rome, their shared passion for antiquity, and their mutual respect (despite occasional professional disagreements, such as one recorded by Vasari concerning a crucifix Donatello carved that Brunelleschi criticized for its peasant-like realism) spurred both artists to greater heights. Brunelleschi's development of linear perspective undoubtedly influenced Donatello's reliefs.

Donatello also had a profound impact on painters. Masaccio, a pioneer of Renaissance painting, shared Donatello's commitment to naturalism, human emotion, and the use of perspective. Masaccio's weighty, three-dimensional figures in frescoes like those in the Brancacci Chapel seem to translate Donatello's sculptural principles into paint. It's even suggested Donatello may have helped Masaccio secure commissions, possibly introducing him to Masolino da Panicale, with whom Masaccio collaborated.

His master, Lorenzo Ghiberti, remained a prominent figure, and though their styles diverged, the competitive environment fostered by patrons commissioning works from both artists (and others like Nanni di Banco, another talented contemporary sculptor at Orsanmichele) pushed them all to innovate. Painters like Paolo Uccello and Andrea del Castagno also absorbed lessons from Donatello's powerful figures and spatial constructions. Uccello, in particular, became almost obsessed with perspective, while Castagno's figures often possess a sculptural solidity reminiscent of Donatello.

Theorists like Leon Battista Alberti codified many of the artistic principles that Donatello intuitively practiced, providing an intellectual framework for the new Renaissance style. Patrons, most notably Cosimo de' Medici, played a crucial role by commissioning ambitious works and fostering a climate of artistic excellence. Donatello's circle also included younger artists who learned from him, such as Michelozzo, with whom he sometimes collaborated on architectural and sculptural projects. Even artists with vastly different sensibilities, like the devout and lyrical painter Fra Angelico or the more worldly Filippo Lippi, were part of this vibrant Florentine scene, contributing to the rich tapestry of the Early Renaissance.

Personality and Anecdotes

Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, paints a vivid picture of Donatello's personality. He is described as a man of simple habits, generous to a fault, and fiercely independent. Vasari recounts that Donatello kept a basket of money suspended from the ceiling in his workshop, from which his assistants and friends could freely take what they needed.

He was also known for his sharp wit and, at times, a fiery temper. One famous anecdote tells of a Genoese merchant who commissioned a bronze head from Donatello but then quibbled about the price, claiming Donatello had only worked on it for a month. Enraged by the merchant's attempt to undervalue his skill and time, Donatello, who was working on a high scaffold at the time, reportedly sent the head crashing to the street below, declaring that the merchant was better at bargaining for beans than for statues. When the merchant, regretting his actions, offered double the price to have it remade, Donatello refused, underscoring his disdain for those who did not respect the value of art and artists.

There are also hints in contemporary accounts and later interpretations of Vasari about Donatello's personal life, including suggestions of his homosexuality, based on his preference for "handsome" apprentices and the sensual nature of works like the bronze David. While definitive proof is lacking, these aspects contribute to the complex and multifaceted image of the artist. Above all, Donatello emerges as a man deeply dedicated to his art, uncompromising in his standards, and unafraid to challenge conventions.

Enduring Legacy: Shaping Western Sculpture

Donatello's death in 1466 marked the end of an era, but his influence was just beginning to permeate Italian and European art. He had fundamentally transformed the art of sculpture, laying the groundwork for the High Renaissance and beyond.

His direct impact can be seen in the work of sculptors like Andrea del Verrocchio, whose own bronze David and equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni clearly engage with Donatello's precedents. Verrocchio, in turn, was the master of Leonardo da Vinci, further extending Donatello's lineage.

But Donatello's most profound artistic heir was arguably Michelangelo Buonarroti. Michelangelo deeply admired Donatello's ability to convey powerful emotion (terribilità), his anatomical understanding, and his psychological insight. Works like Michelangelo's David and his sculptures for the Medici Tombs owe a significant debt to Donatello's pioneering achievements. Other High Renaissance masters like Raphael Sanzio, though primarily a painter, also studied and absorbed the lessons of Donatello's naturalism and compositional dynamism.

Donatello elevated sculpture from a craft to a major intellectual art form. He demonstrated its capacity for profound psychological expression, dramatic narrative, and the embodiment of humanist ideals. His revival of classical forms, his technical innovations, and his unwavering commitment to naturalism set a new course for Western sculpture, influencing countless artists for generations to come. He was, in every sense, a true master of the Florentine Renaissance, whose genius continues to inspire awe and admiration.

Conclusion

Donatello was more than just a sculptor; he was a visionary who redefined the possibilities of his art. From the heroic confidence of his St. George to the introspective sensuality of his bronze David, from the groundbreaking perspective of The Feast of Herod to the raw emotional power of the Penitent Magdalene, his works chart a course of relentless innovation and profound human understanding. He synthesized the lessons of classical antiquity with the spiritual fervor of his own time, creating a body of work that is both timeless and deeply rooted in the cultural ferment of 15th-century Florence. As one of the founding fathers of the Renaissance, Donatello's legacy is immeasurable, his sculptures standing as enduring testaments to the power of human creativity and the enduring quest to capture life in stone and bronze.