James Pradier, born Jean-Jacques Pradier, stands as a significant figure in 19th-century French sculpture. Active during a period of immense artistic and political change, Pradier carved out a distinct niche for himself, blending the rigors of Neoclassicism with a palpable sensuality that captivated audiences and, at times, courted controversy. His journey from Geneva to the pinnacle of the Parisian art world, his prolific output, and his influential role as an academician mark him as an artist whose work merits close examination.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Geneva

Jean-Jacques Pradier was born on May 23, 1790, in Geneva, Switzerland, into a Protestant family. His lineage traced back to French Huguenots who had sought refuge in Switzerland following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes – a historical event that reshaped many families' destinies. This Genevan upbringing, in a city known for its intellectual rigor and Calvinist traditions, provided the initial backdrop to his life. However, it was the call of art that would soon define his path.

From a young age, Pradier exhibited a clear aptitude for the visual arts. His initial training in Geneva was practical, focusing on skills like copperplate engraving. This early grounding in precision and line would subtly inform his later sculptural work. He also pursued painting, broadening his artistic foundations. Geneva, while a cultural center, could not contain his burgeoning ambition. The magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed art capital of Europe, proved irresistible.

Parisian Aspirations and Academic Foundations

In 1807, at the age of seventeen, Pradier made the pivotal move to Paris. This was a city still reverberating from the French Revolution and now under the sway of Napoleon Bonaparte, a period that fostered a grand, heroic Neoclassical style in the arts, championed by figures like the painter Jacques-Louis David. Pradier immersed himself in this stimulating environment, seeking the best possible instruction.

![Psyche [detail #5] (Psyche) by James Pradier](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/247384/m/james-pradier-psyche-detail-5-psyche-b96e528.jpg)

He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the cornerstone of academic art training in France. Here, he entered the studio of François-Frédéric Lemot, a respected sculptor who had himself won the coveted Prix de Rome. Under Lemot's tutelage, Pradier honed his skills in modeling, anatomy, and the classical principles of composition and form. The competitive atmosphere of the École, with its emphasis on historical and mythological subjects, was crucial in shaping his early artistic identity. Some accounts also suggest he may have benefited from the guidance or influence of painters like François Gérard, a student of David, and later, perhaps drawing insights from the linear precision of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, another titan of French Neoclassicism.

The Prix de Rome: A Gateway to Classical Antiquity

The ultimate ambition for any young artist at the École des Beaux-Arts was to win the Prix de Rome. This prestigious scholarship, awarded annually, granted the recipient several years of study at the French Academy in Rome. In 1813, Pradier achieved this distinction in sculpture with his work Neoptolemus Preventing Philoctetes from Firing an Arrow at Ulysses. This relief, demonstrating his mastery of classical narrative and anatomical rendering, opened the doors to Italy.

His time in Rome, from roughly 1814 to 1818 or 1819, was transformative. He was immersed in the masterpieces of classical antiquity – the Roman statuary, the architectural ruins – and the monumental works of Renaissance and Baroque masters like Michelangelo and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Crucially, he was in Rome during the ascendancy of Antonio Canova, the leading Neoclassical sculptor of the age, whose polished surfaces and idealized forms set an international standard. The influence of Canova, and perhaps also the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, another luminary of Roman Neoclassicism, is discernible in Pradier's developing style, particularly in his pursuit of grace and refined finish.

Return to Paris and Salon Success

Pradier returned to Paris around 1819, his artistic vision sharpened and his technical skills considerably advanced. He made his debut at the Paris Salon of 1819 with works such as Centaur and Bacchante and a Reclining Bacchante. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to exhibit their work and gain public and critical recognition. Pradier's submissions immediately attracted attention for their technical polish and their elegant, often sensual, interpretation of classical themes.

Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, Pradier became one of the most celebrated sculptors in France. He was a regular and successful exhibitor at the Salon, receiving numerous commissions from both private patrons and the state. His style, while firmly rooted in Neoclassicism, possessed a distinctive warmth and accessibility. He excelled in depicting the female form, imbuing his figures with a subtle eroticism that distinguished him from the more austere classicism of some of his predecessors, like Jean-Antoine Houdon, or contemporaries.

Signature Style: Neoclassical Grace and Sensuous Forms

Pradier's mature style is characterized by a remarkable synthesis of Neoclassical idealism and a more modern, almost Romantic, sensibility towards the human body, particularly the female nude. His figures, whether mythological goddesses, allegorical personifications, or literary heroines, are typically rendered with smooth, highly polished surfaces, recalling the finish of Canova. However, Pradier's nudes often possess a softer, more yielding quality, a fleshy realism that tempers their classical ideality.

He demonstrated a profound understanding of anatomy, yet his figures rarely appear rigidly academic. Instead, they exude a languid grace, often captured in relaxed, sinuous poses. This ability to infuse classical forms with a contemporary sensuality was key to his popularity. Critics like Théophile Gautier, a prominent writer and art critic, were often admirers of Pradier's skill, though some, like Gustave Flaubert, occasionally found his perfection a little too polished or "cold." This tension between classical restraint and sensual appeal is a hallmark of his oeuvre.

Major Works and Public Commissions

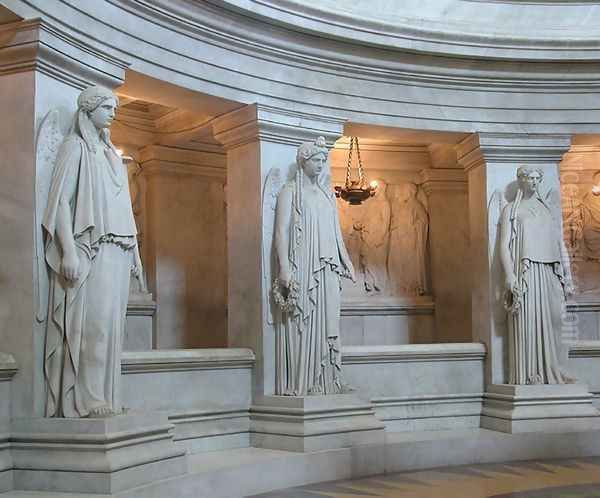

Pradier's prolific career yielded a vast number of significant works, many of which remain iconic. Among his most celebrated Salon pieces is Psyche (1824, Louvre), a delicate and introspective portrayal of the mythological princess. His Three Graces (1831, Louvre) is another masterpiece, showcasing his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with elegance and harmony. These figures, while inspired by classical prototypes, possess a distinctly 19th-century charm.

He was also heavily involved in major public sculptural projects that defined the urban landscape of Paris and national monuments. For the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile, he sculpted the famous Renommées (Fames or Victories) that adorn the spandrels of the main arch, dynamic figures that contribute to the monument's grandeur. He also created sculptures for the Palais Bourbon (the French National Assembly), the Madeleine Church, and the Louvre, including pedimental sculptures. His work for the Palace of Versailles includes the Twelve Victories in the Galerie des Batailles, contributing to the historical narratives championed by King Louis-Philippe. These commissions underscore his status as a favored artist of the July Monarchy.

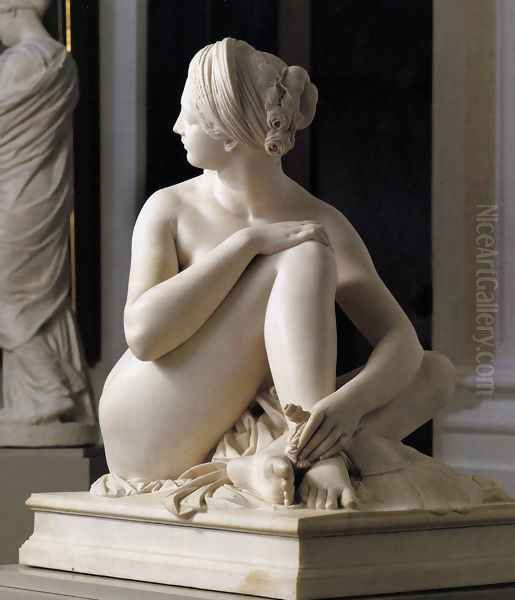

Other notable works include his Odalisque (1841, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon), which, with its exotic theme and reclining pose, shows an engagement with Romantic themes popularised by painters like Ingres and Eugène Delacroix, albeit rendered in Pradier's characteristically smooth style. His Satyr and Bacchante (1834, Louvre), a dynamic and overtly erotic group, caused a scandal at the Salon and was initially refused purchase by the state due to its perceived indecency, highlighting the provocative edge his sensuality could sometimes take. It was later acquired by the Louvre, a testament to its artistic merit.

His later work, Sappho (1852, Musée d'Orsay), completed in the year of his death, is a poignant and powerful depiction of the ancient Greek poetess. Here, the classical form is imbued with a deep sense of melancholy and introspection, reflecting perhaps a more Romantic emotional depth. He also produced numerous portrait busts and smaller decorative pieces, demonstrating his versatility.

Pradier as an Academician and Teacher

Beyond his personal artistic production, Pradier played a significant role in the French art establishment. In 1827, he was elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts, succeeding his former master Lemot. The following year, in 1828, he was appointed a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, a position he held for the rest of his life. This was a highly influential role, allowing him to shape the next generation of sculptors.

As a professor, he would have imparted the academic principles of drawing from the antique, life drawing, and the hierarchy of genres. While his own work pushed the boundaries of Neoclassical sensuality, his teaching would have been grounded in the established curriculum. His success and official recognition made him a powerful figure in the academic art world, a world that also included sculptors like François Rude, known for a more overtly Romantic and dynamic style (as seen in his Departure of the Volunteers of 1792, or La Marseillaise, on the Arc de Triomphe), and David d'Angers, celebrated for his portrait medallions and monumental sculptures. Pradier's studio was a popular one, attracting many aspiring artists.

Personal Life: Art, Love, and Society

Pradier's personal life was as vibrant and, at times, as complex as his artistic career. He was a prominent figure in Parisian society, known for his charm and wit. His studio was a lively hub, frequented by artists, writers, and society figures.

The most famous aspect of his personal life was his long and passionate affair with Juliette Drouet. Drouet, an actress, became Pradier's model and mistress in the 1820s. She later became the lifelong companion of the literary giant Victor Hugo. Pradier's relationship with Drouet, even after she became involved with Hugo, seems to have continued in some form for many years, creating a complicated triangle. Letters reveal the intensity of their early bond. Pradier also had a wife, Louise d'Arcet, whom he married in 1825 and with whom he had children, but this marriage was reportedly unhappy and eventually ended in separation. His relationship with Drouet, however, remained a defining feature of his personal narrative, linking him to the Romantic literary circles of Hugo, Alfred de Musset, and others.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Pradier worked during a dynamic period in French art, often characterized by the interplay and sometimes tension between Neoclassicism and emerging Romanticism. While painters like Jacques-Louis David had established a severe Neoclassicism, and Ingres continued a highly refined classical tradition, the Romantic fervor of Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix offered a powerful alternative, emphasizing emotion, drama, and color.

In sculpture, Pradier's refined Neoclassicism found parallels in the work of artists like François Joseph Bosio or Jean-Pierre Cortot. However, his particular emphasis on sensuous beauty set him apart. He was less overtly heroic than some Neoclassicists and less dramatically expressive than Romantics like Rude or Antoine-Louis Barye, the great animalier sculptor. Pradier carved his own path, creating a style that was both academically sound and immensely appealing to contemporary tastes. His success can be measured by the sheer volume of his commissions and the esteem in which he was held by patrons and the public.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

James Pradier remained active and highly regarded until his death. He continued to produce significant works and fulfill his academic duties. He passed away suddenly on June 4, 1852, in Bougival, near Paris, reportedly after an excursion. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, the final resting place of many illustrious figures.

In the decades following his death, Pradier's reputation, like that of many academic artists of the 19th century, experienced a decline as new artistic movements like Realism and Impressionism gained ascendancy. His polished surfaces and idealized subjects seemed out of step with the avant-garde's focus on contemporary life and more experimental forms.

![Satyre et Bacchante [detail #1] (Satyr and Bacchante) by James Pradier](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/247375/m/james-pradier-satyre-et-bacchante-detail-1-satyr-and-bacchante-a0eb1551.jpg)

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a renewed appreciation for 19th-century academic art, and Pradier's work has been re-evaluated. Art historians now recognize his technical brilliance, the distinctive character of his sensuous Neoclassicism, and his significant contribution to the artistic landscape of his time. His sculptures, found in major museums worldwide, continue to fascinate viewers with their blend of classical elegance and timeless human appeal. He influenced a generation of sculptors who passed through his studio, and his public works remain integral to the monumental heritage of Paris. Later sculptors, such as Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, while developing a more naturalistic and emotionally charged style, built upon the academic foundations that Pradier represented, evolving the tradition of French sculpture.

Conclusion: An Enduring Appeal

James Pradier was more than just a technically proficient sculptor. He was an artist who skillfully navigated the artistic currents of his time, creating a body of work that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continues to engage audiences today. His ability to imbue the cool marble of Neoclassicism with warmth, life, and a distinct sensuality secured his place as one of the most successful and recognizable sculptors of the July Monarchy. From the grandeur of his public monuments to the intimate charm of his female figures, Pradier's art remains a testament to his enduring talent and his unique position within the rich tapestry of 19th-century European art. His legacy is one of refined beauty, technical mastery, and a subtle understanding of the enduring allure of the classical form.