John Reinhard Weguelin (1849–1927) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late Victorian art. An accomplished painter in both oils and watercolors, as well as a talented illustrator, Weguelin carved a niche for himself with his evocative depictions of classical antiquity, mythological narratives, and idyllic pastoral scenes. His work, deeply rooted in the Neoclassical tradition yet infused with a distinctly Victorian sensibility, offers a captivating window into the artistic preoccupations and aesthetic ideals of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on June 23, 1849, in the village of South Stoke, near Arundel in Sussex, England, John Reinhard Weguelin's early life provided an international backdrop that would subtly inform his artistic perspective. Though English by birth, he spent a significant portion of his childhood abroad, notably in Italy and Germany. This exposure to the rich artistic and cultural heritage of continental Europe, particularly the lingering grandeur of Rome, likely planted the seeds for his lifelong fascination with the classical world.

His formal artistic education commenced in London. Weguelin initially enrolled at the South Kensington Art School, a key institution for design and applied arts. However, his ambitions lay in fine art, leading him to the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. At the Slade, he studied under Edward Poynter, a leading figure in British Neoclassicism and a staunch advocate for academic drawing and classical subjects. Poynter's influence was considerable, instilling in Weguelin a respect for meticulous draughtsmanship, historical accuracy, and the grand themes of antiquity. He further honed his skills at the Royal Academy Schools, immersing himself in the academic traditions that still held sway in the British art establishment.

Weguelin's formative years as an artist coincided with a period of intense classical revivalism in Britain. The Victorian era, despite its industrial progress and imperial expansion, harbored a deep nostalgia for the perceived order, beauty, and heroism of ancient Greece and Rome. Artists like Frederic Leighton, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Albert Moore were at the forefront of this movement, creating elaborate and often archaeologically informed reconstructions of classical life. Weguelin was undoubtedly aware of their work and shared their passion for these ancient civilizations.

The Influence of Neoclassicism and Key Contemporaries

The dominant artistic current that shaped Weguelin's early career was Neoclassicism, particularly the Victorian iteration often referred to as "Olympianism" or "Classical Revival." This movement sought to emulate the art of ancient Greece and Rome, emphasizing clarity, order, idealized human forms, and noble subjects.

Sir Edward John Poynter, Weguelin's tutor at the Slade, was a pivotal influence. Poynter's own work, such as "Israel in Egypt" (1867) and "A Visit to Aesculapius" (1880), demonstrated a commitment to historical detail and grand narrative composition. He encouraged his students to study classical sculpture and architecture, and to ground their imaginative scenes in plausible historical settings.

Perhaps an even more pervasive influence on Weguelin, and many of his contemporaries, was Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Alma-Tadema, a Dutch-born painter who settled in England, became immensely popular for his meticulously detailed and sun-drenched depictions of everyday life in ancient Rome and Pompeii. His ability to render marble, textiles, and architectural elements with astonishing realism, combined with his charming, often anecdotal, subject matter, set a standard for classical genre painting. Weguelin's attention to archaeological detail, his interest in the domestic and leisurely aspects of ancient life, and his luminous palette often echo Alma-Tadema's approach, though Weguelin frequently ventured into more overtly mythological and fantastical realms.

Other prominent figures of the Neoclassical movement whose work would have formed the backdrop to Weguelin's development include Frederic, Lord Leighton, President of the Royal Academy. Leighton's paintings, such as "Flaming June" (c. 1895) and "The Bath of Psyche" (c. 1890), were celebrated for their sensuous beauty, harmonious compositions, and idealized figures. Albert Moore, another contemporary, focused on creating decorative arrangements of figures, often in classical drapery, emphasizing aesthetic harmony over narrative content, as seen in works like "A Summer Night" (1890). George Frederic Watts, while often more allegorical, also drew heavily on classical forms and themes in works like "Hope" (1886).

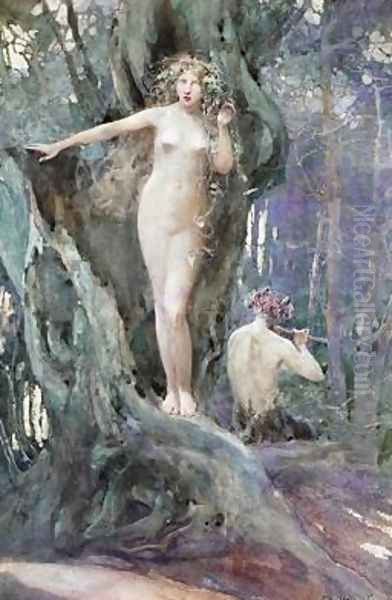

Weguelin absorbed these influences, developing a style characterized by careful drawing, a bright and often delicate color palette, and a talent for creating idyllic and dreamlike atmospheres. He was particularly adept at rendering the human form, especially the female nude, which he depicted with a grace and sensuality that was both classical and distinctly Victorian.

Major Themes and Subjects in Weguelin's Art

Weguelin's oeuvre is rich with themes drawn from classical mythology, ancient history, and pastoral poetry. He demonstrated a particular fondness for subjects that allowed him to explore beauty, nature, and the more lyrical or enchanting aspects of the ancient world.

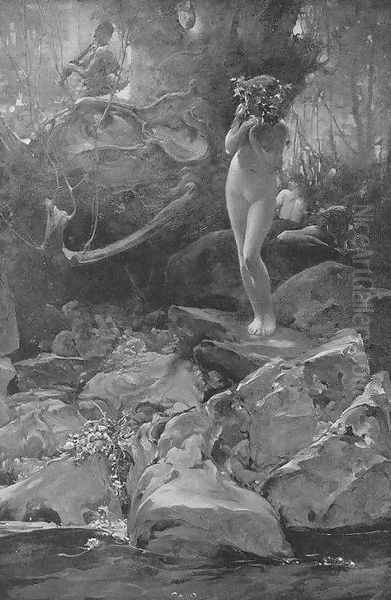

Classical Mythology and Legend: Greek and Roman myths provided an inexhaustible source of inspiration. Weguelin was drawn to stories featuring gods, goddesses, nymphs, satyrs, and mortals caught in divine dramas. He often chose moments of quiet reflection, enchantment, or pastoral bliss rather than scenes of violent conflict. His depictions of Pan, the mischievous god of the wild, and his attendant nymphs are recurrent, showcasing his ability to blend the human and the fantastical within natural settings. Works like "The Magic of Pan's Flute" exemplify this, capturing the irresistible allure of the rustic god's music.

Ancient Daily Life: Following the precedent set by Alma-Tadema, Weguelin also painted scenes of everyday life in ancient Greece and Rome. These works often feature leisurely pursuits, domestic interiors, and garden scenes. "The Bath" is a fine example, depicting women in a classical setting, rendered with attention to costume and architectural detail, yet imbued with a gentle, almost intimate, atmosphere. These paintings allowed Victorian audiences to imagine themselves into the ancient past, finding parallels and contrasts with their own lives.

Pastoral and Arcadian Visions: A strong current of pastoralism runs through Weguelin's art. He excelled at creating idyllic landscapes populated by graceful figures, often in harmonious communion with nature. These Arcadian scenes, evoking a mythical golden age of peace and simplicity, resonated with a Victorian society grappling with the rapid changes of industrialization and urbanization. "The Piper and the Nymphs" captures this idyllic spirit, with its sun-dappled woodland setting and ethereal figures.

Folklore and Fairy Tales: Beyond the classical, Weguelin also explored themes from folklore and fairy tales, particularly in his illustration work. His ability to create enchanting and otherworldly atmospheres lent itself well to these subjects. His illustrations for Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tales are notable in this regard. He also painted subjects like mermaids, as seen in "The Mermaid of Zennor," a theme popular with other Victorian artists like John William Waterhouse and Edward Burne-Jones.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of Weguelin's artistic achievements and thematic concerns.

Lesbia (1878): One of his earlier successes, exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery, "Lesbia" depicts the beloved of the Roman poet Catullus. The painting shows Lesbia with her pet sparrow, a reference to Catullus's famous poems. It showcases Weguelin's emerging skill in rendering classical figures and his interest in the more personal and romantic aspects of ancient literature. The delicate handling of the subject and the intimate mood are characteristic.

The Obsequies of an Egyptian Cat (1886): Perhaps one of Weguelin's most famous and intriguing works, this painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy. It depicts a solemn funeral procession for a mummified cat in ancient Egypt, complete with priests, mourners, and offerings. The Victorians were fascinated by ancient Egyptian culture, fueled by archaeological discoveries and the decipherment of hieroglyphs. Weguelin's painting taps into this Egyptomania, demonstrating his research into Egyptian customs and his ability to create a scene that is both exotic and emotionally resonant. The meticulous detail, from the hieroglyphs on the wall to the costumes of the figures, is remarkable. This work aligns him with other artists exploring Egyptian themes, such as Poynter and even the French Orientalist Jean-Léon Gérôme.

The Gardens of Adonis (1888): This painting illustrates a poignant myth. Adonis, the beautiful youth beloved by Aphrodite (Venus), was gored to death by a wild boar. The "Gardens of Adonis" were short-lived plants grown in his honor, symbolizing the brevity of life and beauty. Weguelin's interpretation likely focuses on the lush, ephemeral beauty associated with the myth, perhaps depicting Aphrodite mourning or the nymphs tending to the symbolic gardens. It is a subject that allows for rich color and a melancholic, romantic mood. The painting is housed in the Northampton Museum and Art Gallery.

The Roman Saturnalia (1884): This work captures the spirit of the ancient Roman festival of Saturnalia, a period of feasting, revelry, and social inversion. Weguelin likely depicted a scene of joyful abandon, showcasing his ability to handle multi-figure compositions and convey a sense of lively movement and celebration. Such scenes of ancient festivals were popular, offering a glimpse into the more exuberant aspects of classical life.

Psyche: The myth of Cupid and Psyche was a favorite among Victorian artists, offering themes of love, trial, and eventual apotheosis. Weguelin's interpretation would likely focus on Psyche's beauty and vulnerability, or perhaps one of the tasks she had to endure. Artists like Leighton and Burne-Jones also famously depicted scenes from this story.

The Illustrator and Watercolorist

While his oil paintings of classical and mythological scenes formed the core of his reputation, John Reinhard Weguelin was also a highly accomplished illustrator and watercolorist.

Around 1893, Weguelin began to focus more intently on watercolor. This medium, with its potential for luminosity and delicate effects, suited his interest in ethereal subjects and atmospheric landscapes. He was elected a member of the Royal Watercolour Society (RWS) in 1897 (having been an associate since 1894), a testament to his skill in this demanding medium. His watercolors often feature pastoral landscapes, garden scenes, and mythological figures, rendered with a lighter touch and a bright, airy palette.

His work as an illustrator brought his art to a wider audience. He provided illustrations for several books, most notably:

Thomas Babington Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome (1881 edition): This collection of narrative poems about heroic episodes in Roman history was a popular Victorian text. Weguelin's illustrations would have complemented Macaulay's stirring verses, bringing the ancient Roman world to life for readers.

Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales (1893 edition): Weguelin's style was well-suited to the magical and often poignant world of Andersen's stories. His depictions of mermaids, fairies, and enchanted landscapes would have captivated young and old readers alike. This work places him in the company of other great Victorian and Edwardian illustrators like Arthur Rackham, Walter Crane, and Edmund Dulac, who also brought classic tales to life.

The poems of Catullus: Given his early success with "Lesbia," it is fitting that he also illustrated editions of Catullus, further exploring the world of the Roman poet.

These illustration projects not only provided a steady income but also allowed Weguelin to explore narrative and fantasy in a different format, often with more freedom than the constraints of large-scale exhibition oils.

Orientalist Influences and Travels

While primarily known for his classical subjects, Weguelin, like many artists of his time, was also touched by the allure of "the Orient." The 19th century saw a surge of European interest in the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East, and beyond. This "Orientalism" manifested in art through depictions of exotic landscapes, bustling marketplaces, harem scenes, and historical events set in these regions.

Weguelin undertook travels to Spain, Morocco, and, significantly, Egypt. These journeys undoubtedly enriched his visual vocabulary and provided firsthand experience of the light, colors, and cultural details of these lands. His painting "The Obsequies of an Egyptian Cat" is a clear product of this interest, though it predates some of his more extensive travels, suggesting an early fascination nurtured by archaeological reports and museum collections. His later works may have incorporated more direct observations from his travels, adding an authentic touch to his depictions of ancient or exotic scenes.

This places him in a broader tradition of British Orientalist painters such as John Frederick Lewis, who lived in Cairo for many years and was renowned for his detailed scenes of Egyptian life, and David Roberts, famous for his topographical views of Egypt and the Holy Land. While Weguelin's Orientalism was perhaps less central to his oeuvre than it was for these artists, it was nonetheless a significant facet of his artistic explorations.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Reception

Weguelin's style is characterized by its clarity, elegance, and meticulous attention to detail. His figures are typically well-drawn and idealized, conforming to classical proportions. He had a fine sense of color, often employing a bright, luminous palette that lent his scenes an airy, sunlit quality. His compositions are generally balanced and harmonious, reflecting academic principles.

In his oil paintings, he often achieved a smooth, polished finish, similar to that of Alma-Tadema or Poynter. His handling of textures – marble, water, foliage, and drapery – was particularly skilled. In his watercolors, he demonstrated a lighter touch, exploiting the transparency of the medium to create delicate washes and vibrant hues. He was especially adept at capturing the effects of light, whether it be the dappled sunlight of a woodland glade or the bright Mediterranean sun illuminating a classical ruin.

During his lifetime, Weguelin achieved considerable recognition. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from 1877, as well as at the Grosvenor Gallery (a more progressive alternative to the RA, favored by artists like Burne-Jones) and the New Gallery. His election to the Royal Watercolour Society was a mark of esteem from his peers. His work was popular with a public that appreciated classical themes, skilled execution, and narrative clarity.

However, like many Victorian academic painters, Weguelin's reputation declined in the early 20th century with the rise of Modernism. The avant-garde movements, such as Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism, championed new forms of expression that diverged sharply from the narrative and representational traditions of the 19th century. Artists like Roger Fry and Clive Bell, influential critics in Britain, championed these new movements and often dismissed Victorian academic art as sentimental or irrelevant.

Comparison with John William Waterhouse

It is insightful to compare Weguelin with his contemporary John William Waterhouse (1849–1917), who was born in the same year. Both artists shared an interest in mythological and legendary subjects, particularly those featuring beautiful and often enigmatic female figures. Waterhouse, often associated with late Pre-Raphaelitism and Symbolism, is known for works like "The Lady of Shalott," "Hylas and the Nymphs," and "A Mermaid."

While both artists depicted similar themes, their stylistic approaches differed. Waterhouse's style often had a richer, more painterly quality, with a deeper, more jewel-like palette and a more overtly romantic or melancholic mood. Weguelin's classicism tended to be brighter, more serene, and perhaps more archaeologically grounded, especially in his Roman scenes. However, in their depictions of nymphs, mermaids, and mythological heroines, there are clear parallels in their shared Victorian fascination with these subjects. The provided information suggests a degree of competition, which is plausible given their overlapping thematic interests and shared exhibition venues. Both artists catered to a similar taste for romanticized depictions of myth and legend.

Later Life and Legacy

John Reinhard Weguelin continued to paint and exhibit into the early 20th century. He lived for many years in Hastings, a coastal town in Sussex, which may have provided inspiration for his seascapes and mermaid paintings. He passed away on April 28, 1927, in Hastings.

For several decades after his death, Weguelin, along with many of his Victorian contemporaries, was largely forgotten by the art historical mainstream. However, the latter half of the 20th century saw a significant reassessment of Victorian art. Scholars and collectors began to rediscover the technical skill, imaginative power, and cultural significance of artists like Weguelin. His paintings started to reappear in exhibitions and at auction, commanding renewed interest and appreciation.

Today, John Reinhard Weguelin is recognized as a talented and distinctive voice within the Victorian Neoclassical tradition. His works are valued for their charm, their technical accomplishment, and their evocative portrayal of a world of myth, legend, and ancient beauty. His paintings can be found in public collections, including the Tate Britain (which holds his "Lesbia"), the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (which holds "The Obsequies of an Egyptian Cat"), and the Northampton Museum and Art Gallery.

His art offers a fascinating glimpse into the Victorian imagination, with its complex interplay of nostalgia for the past, a desire for beauty and order, and a fascination with the exotic and the fantastical. He successfully navigated the demands of academic tradition while infusing his work with a personal vision, creating a body of work that continues to enchant and engage viewers today. He remains a testament to the enduring appeal of classical themes and the skilled artistry of a bygone era.