Charles Robinson stands as a pivotal figure in the history of British illustration, particularly during the vibrant period often referred to as the "Golden Age" at the turn of the 20th century. Born in Islington, London, in 1870, he emerged from an artistic family, yet carved a unique path defined by innate talent, a distinctive decorative style, and a profound connection to the world of children's literature. His life, spanning until 1937, witnessed significant shifts in art and publishing, and his contributions left an indelible mark on how generations visualized classic tales.

Early Life and Artistic Emergence

Charles Robinson entered the world as the son of Thomas Robinson, himself an illustrator. Artistry ran deep in the family, with Charles's brothers, Thomas Heath Robinson and William Heath Robinson, also achieving fame as illustrators. Despite this environment, Charles did not pursue formal art education. Instead, his path was shaped by inherent skill and a passion for drawing, which became evident early on. He initially honed his craft through practical application, undertaking apprenticeships and working various jobs, including a period with the printers Waterlow and Sons.

His initial forays into professional illustration involved creating artwork for children's primers, including contributions to publications by Macmillan. These early efforts did not go unnoticed. The influential art magazine, The Studio, provided positive commentary on his work, praising its potential. This recognition proved crucial. In 1895, following a feature in The Studio, Robinson caught the attention of the publisher John Lane of The Bodley Head.

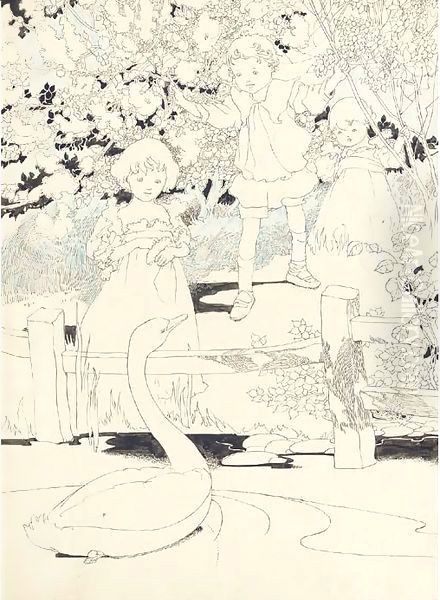

This connection led to a significant commission: illustrating Robert Louis Stevenson's beloved collection of poetry, A Child's Garden of Verses. Published in 1895, Robinson's illustrations for this volume were a resounding success. They captured the innocence, wonder, and imaginative spirit of Stevenson's poems with remarkable sensitivity and decorative flair. This project catapulted Robinson to prominence and established his reputation as a leading illustrator, particularly for children's material.

Artistic Style and Defining Influences

Charles Robinson developed a highly distinctive and recognizable artistic style. It was characterized by a remarkable proficiency in line work, often executed with pen and ink, resulting in clean, bright, and exceptionally decorative compositions. His approach masterfully blended intricate detail with a sense of lightness and fantasy. While line was fundamental, he also skillfully incorporated watercolour, adding depth, atmosphere, and subtle colour harmonies to his pieces.

His style was not formed in isolation but drew from a rich tapestry of influences. The Arts and Crafts movement, particularly the ethos championed by figures like William Morris and Walter Crane, resonated deeply with Robinson. This is evident in his holistic approach to book design, viewing the entire volume as an art object where illustrations, typography, and layout worked in concert. He shared Crane's belief in the importance of high-quality, aesthetically pleasing books accessible to a wider audience.

The sinuous lines and organic forms of Art Nouveau also left a clear imprint on his work. This influence can be seen in the flowing contours of his figures, the decorative borders he often employed, and the overall elegance of his compositions. Furthermore, the meticulous detail and narrative intensity associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood can be detected as an underlying sensibility, particularly in his attention to texture and pattern. Some analyses also suggest an awareness of early Venetian printing techniques and the groundbreaking linearity of Aubrey Beardsley, though Robinson's work maintained a gentler, less decadent tone than Beardsley's.

Robinson possessed a profound understanding of illustration's decorative potential. His images were not mere representations of text but functioned as beautiful objects in their own right, enhancing the reading experience through visual delight. He demonstrated technical versatility, mastering both pen-and-ink and watercolour, and effectively utilized emerging printing technologies, like lithography, to bring his colourful visions to a broad public. His style was often described as romantic, poetic, lively, and deeply inspiring.

Major Works and Contribution to Children's Literature

Following the success of A Child's Garden of Verses, Charles Robinson became a highly sought-after illustrator for children's books, contributing significantly to the visual landscape of the Golden Age of Illustration. His bibliography is extensive, showcasing his ability to adapt his style to a wide range of classic texts while retaining his signature charm.

Among his most celebrated works are his illustrations for Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. He brought a unique, whimsical, and decorative interpretation to this iconic story, distinct from earlier renditions by artists like John Tenniel. His illustrations for Grimm's Fairy Tales and Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales (the latter notably produced in collaboration with his brothers Thomas and William Heath Robinson) further cemented his reputation. These editions captured the magic, peril, and wonder inherent in these traditional stories.

Other significant projects included illustrations for Oscar Wilde's The Happy Prince and Other Tales, where his delicate style perfectly complemented the poignant beauty of Wilde's prose. He also provided memorable artwork for Frances Hodgson Burnett's The Secret Garden, capturing the transformative power of nature and friendship central to the novel. His illustrations for Percy Bysshe Shelley's The Sensitive Plant (often published as The Sensitive Plant and Early Poems) are considered among his finest achievements, showcasing his ability to interpret lyrical poetry with visual grace.

Robinson's contribution extended beyond individual titles. He was prolific, illustrating over 100 books throughout his career. His work frequently appeared in leading periodicals of the day, such as The Graphic and Black and White, bringing his art to an even wider audience. His consistent output and the high quality of his work firmly established him alongside other luminaries of the Golden Age, such as Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, and Kay Nielsen, each contributing their unique vision to the era's rich illustrative tradition.

Collaborations and Contemporary Connections

The artistic landscape Charles Robinson inhabited was one of both collaboration and creative competition. His most notable collaboration was with his own brothers, Thomas Heath Robinson and William Heath Robinson. Their joint effort on Andersen's Fairy Tales is a fascinating example, showcasing the interplay of their distinct yet related styles within a single volume. While collaborative, such projects inevitably highlighted individual artistic identities.

Robinson's influence extended to other artists. The illustrator Anne Anderson, known for her charming depictions of children, acknowledged Robinson's impact on her style, alongside that of Jessie M. King. This indicates Robinson's standing within the illustration community and his role in shaping emerging trends. His work existed within a dialogue with contemporaries, absorbing influences while also contributing to the evolving visual language of the time.

He was clearly aware of the dominant artistic currents. His engagement with the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement, as promoted by William Morris and Walter Crane, and his adaptation of Art Nouveau aesthetics, seen in the work of artists like Aubrey Beardsley (though with a different sensibility), demonstrate his connection to broader artistic developments. He navigated these influences, integrating elements that resonated with his own vision while forging a unique artistic path. His success depended not only on talent but also on skillfully positioning his work within the contemporary art market and publishing world.

Later Life, Recognition, and Legacy

The First World War inevitably impacted life and work in Britain, but Charles Robinson continued his artistic practice in the post-war years. While illustration remained central, he increasingly focused on watercolour painting as an independent art form. His skill in this medium gained formal recognition in 1932 when he was elected a member of the prestigious Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI). This honour acknowledged his mastery beyond the realm of book illustration.

Robinson maintained an active presence in artistic circles. He was known to be a member of sociable groups like the Frothfinders' Club and the London Sketch Club, organizations that brought together artists, illustrators, and writers for camaraderie and creative exchange. These memberships suggest a collegial aspect to his professional life, engaging with fellow creatives in the vibrant London art scene.

His personal life provided a stable foundation. In 1897, he married Edith Mary Fawett, and together they raised a family of six children. He remained dedicated to his craft throughout his later years, continuing to produce artwork and engage with the art world.

Charles Robinson passed away in the summer of 1937 at the age of 67. He left behind a rich legacy as one of the most accomplished and beloved illustrators of the Golden Age. His unique blend of decorative elegance, linear precision, and imaginative sensitivity brought countless classic stories to life for generations of readers. His work continues to be admired and collected today, valued for its artistic merit, its historical significance, and its enduring ability to evoke the magic and wonder of childhood. He remains an essential figure in the study of illustration history, representing a high point in the art of the book.