John Singer Sargent stands as one of the most celebrated and technically gifted painters of his era. An American expatriate who spent most of his life in Europe, he became the preeminent society portraitist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, capturing the elegance, confidence, and sometimes the underlying anxieties of the transatlantic elite. His work, characterized by dazzling brushwork, a sophisticated understanding of light, and an uncanny ability to convey the personality of his sitters, bridges the traditions of the Old Masters with the innovations of Impressionism. Though primarily known for his portraits, Sargent was also a master of landscape, watercolor, and mural painting, demonstrating remarkable versatility throughout his prolific career.

An Expatriate's Beginning: Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Singer Sargent was born on January 12, 1856, in Florence, Italy, to wealthy American parents, Dr. Fitzwilliam Sargent, an eye surgeon from Philadelphia, and Mary Newbold Singer, an amateur artist and heiress to a mercantile fortune. His parents had chosen a nomadic life abroad after the death of their first child. This expatriate existence defined Sargent's upbringing; the family moved seasonally between Italy, France, Germany, and Switzerland, immersing young John in the rich cultural tapestry of Europe from his earliest years.

This unconventional childhood meant Sargent received little formal schooling in the traditional sense. His education was largely overseen by his parents. His father tutored him in subjects like geography, arithmetic, and literature, while his mother, recognizing his burgeoning artistic talent, actively encouraged his drawing and painting pursuits. She ensured he had access to sketchbooks and took him to galleries and churches, fostering an early appreciation for the masterpieces of European art. He became fluent in Italian, French, and German, alongside his native English.

Sargent's innate artistic abilities were evident early on. He was a keen observer, constantly sketching the sights around him during the family's travels. His mother arranged for informal art lessons, and he received some initial guidance in Rome. A more structured phase of his art education began when the family settled temporarily in Florence, where he enrolled at the Accademia delle Belle Arti between 1873 and 1874. However, the pivotal moment in his artistic formation came in 1874 when, at the age of eighteen, he moved to Paris.

Recognizing Paris as the epicenter of the art world, Sargent sought out the best instruction. He passed the rigorous entrance examination for the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the official state-sponsored art school. More significantly, he entered the private atelier of the fashionable portrait painter Carolus-Duran. This decision proved crucial. Carolus-Duran, though a successful society painter himself, advocated a modern approach that broke from strict academic methods. He encouraged direct painting (alla prima), working straight onto the canvas with loaded brushes, emphasizing tonal values and capturing the immediate impression of the subject, rather than relying on meticulous preliminary drawings.

Carolus-Duran's teaching profoundly shaped Sargent's technique, particularly his fluid brushwork and focus on capturing the overall effect. Sargent quickly became his star pupil. During his time in Paris, Sargent also immersed himself in the city's vibrant art scene. He studied the Old Masters at the Louvre, particularly admiring the work of Spanish master Diego Velázquez, whose influence is palpable in Sargent's later work, and Dutch painter Frans Hals. He also absorbed the innovations of contemporary French artists, including the Realism of Gustave Courbet and the burgeoning Impressionist movement led by figures like Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, and Edgar Degas, whose daring compositions and focus on modern life resonated with him.

Ascending in Paris: Early Success and Developing Style

Sargent's talent blossomed rapidly under Carolus-Duran's tutelage and within the stimulating environment of Paris. He made his debut at the official Paris Salon, the most important art exhibition in the world at the time, in 1877 with a portrait of his childhood friend Fanny Watts. His technical facility and sophisticated style quickly garnered attention and praise.

In 1879, he exhibited a striking portrait of his master, Carolus-Duran, a work that demonstrated his confident handling of paint and his ability to convey personality. This painting earned him an honorable mention at the Salon and solidified his reputation as a rising star. During these early years, Sargent also undertook influential study trips. A journey to Spain in 1879 proved particularly significant. There, he meticulously copied works by Velázquez at the Prado Museum in Madrid, deepening his understanding of tonal painting and bravura brushwork. The trip also inspired works infused with Spanish themes and atmosphere, most notably the dramatic and sensual El Jaleo (1882), depicting a flamenco dancer, which caused a sensation when exhibited.

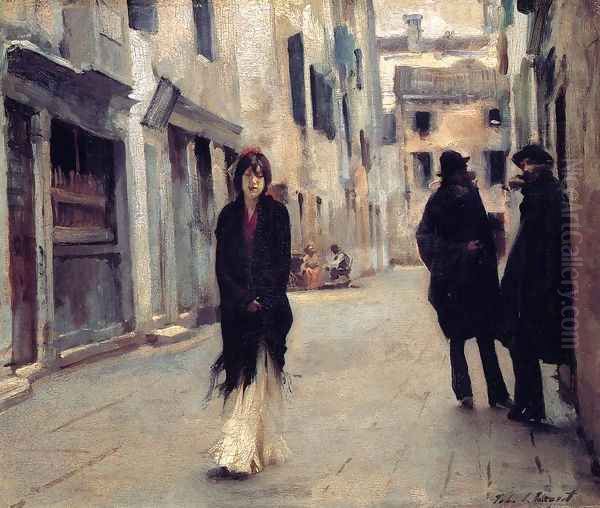

He also traveled to Morocco and later frequently visited Venice, finding endless inspiration in its unique light, architecture, and daily life. Works like Street in Venice (c. 1882) showcase his ability to capture fleeting moments and atmospheric effects with a seemingly effortless touch, blending observed reality with an almost Impressionistic sensibility.

His early portraits from this period, such as the elegant Madame Ramon Subercaseaux (1880), already displayed the hallmarks of his mature style: sophisticated compositions, a keen eye for fashion and social nuance, and brushwork that was both descriptive and expressive. He was adept at capturing the textures of luxurious fabrics and the play of light on surfaces, yet his focus remained on the character of the sitter. He was quickly becoming a sought-after portraitist within the cosmopolitan circles of Paris.

The Scandal of Madame X and the London Relocation

Sargent's rising trajectory in Paris hit a major obstacle in 1884 with the exhibition of what would become his most famous, and infamous, painting: Portrait of Madame X. The sitter was Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, a beautiful American expatriate married to a French banker, known in Parisian society for her striking looks and unconventional style. Sargent saw her as the epitome of modern Parisian elegance and actively sought the commission, hoping the portrait would be his masterpiece and cement his status.

He worked on the portrait for over a year, producing numerous preparatory studies. The final painting depicted Madame Gautreau in a dramatic profile pose, wearing a sleek black satin dress with jeweled straps, her skin unnaturally white against a dark background. The composition was daringly minimalist and intensely stylish, emphasizing her statuesque figure and aristocratic hauteur. Sargent submitted it to the 1884 Paris Salon under the title Portrait de Mme .

The reaction was immediate and overwhelmingly negative. Critics and the public were shocked by what they perceived as the portrait's arrogance and artificiality. The main point of contention, however, was the depiction of Madame Gautreau's dress strap suggestively slipping off her right shoulder. This detail was deemed excessively provocative and indecent. The sitter herself was humiliated by the scandal, and her family was outraged. The controversy effectively stalled Sargent's burgeoning career in Paris. Commissions dried up, and the social circles that had previously welcomed him grew cool.

Sargent was deeply affected by the hostile reception. He later repainted the shoulder strap to sit properly on her shoulder, hoping to quell the criticism, but the damage was done. He kept the painting for many years, eventually exhibiting it under the more enigmatic title Madame X. In 1916, shortly after Gautreau's death, he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, famously stating, "I suppose it is the best thing I have done."

The Madame X scandal was a turning point. Disheartened by the Parisian art world's reaction and sensing limited prospects, Sargent began spending more time in England. By 1886, he had permanently relocated his studio to London, a city that would prove far more receptive to his talents and where he would achieve the height of his fame as a portrait painter. The move marked the end of his Parisian chapter but the beginning of his reign as the undisputed master of society portraiture in the English-speaking world.

The London Years: The Pinnacle of Portraiture

Settling in London opened a new and immensely successful chapter in Sargent's career. While initially facing some resistance from the more conservative elements of the British art establishment, his undeniable talent and cosmopolitan flair soon won him acceptance and then acclaim. London, and increasingly America, provided a steady stream of wealthy and influential clients eager to be immortalized by his brush.

His studio in Tite Street, Chelsea, previously occupied by James McNeill Whistler, became a hub for the fashionable elite. Sargent's portraits from this period are characterized by their dazzling virtuosity, psychological insight, and sheer elegance. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture not just a likeness, but the very essence of his sitters – their confidence, social standing, and individual personalities. His brushwork became even more fluid and assured, often described as "bravura," applying paint with seeming effortlessness yet achieving remarkable effects of light, texture, and form.

Among the masterpieces of his London period is Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885-86), a charming depiction of two young girls lighting Japanese lanterns in a garden at twilight. Painted outdoors over two summers in the Impressionist manner to capture the specific effects of dusk, it was a departure from portraiture that earned him election as an associate of the Royal Academy. However, portraiture remained his primary focus and source of income.

He painted leading figures of British society, aristocracy, and the arts. Works like Lady Agnew of Lochnaw (1892) exemplify his mature style: the sitter gazes directly and engagingly at the viewer, her pose relaxed yet elegant, the handling of her dress a symphony of mauve, white, and grey brushstrokes. Mrs. Hugh Hammersley (1892), with her dynamic pose on a crimson sofa, showcases his ability to create visually exciting compositions and capture a sense of vibrant personality.

His group portraits were equally masterful. The Wyndham Sisters: Lady Elcho, Mrs. Adeane, and Mrs. Tennant (1899) is a monumental work depicting three aristocratic sisters in opulent surroundings, a stunning display of Edwardian elegance and Sargent's compositional skill. He also frequently painted American clients who traveled to London or commissioned him during his increasingly frequent trips back to the United States. Portraits like Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes (1897), depicting the young couple in sporting attire, show a more informal and distinctly American energy. He painted prominent figures such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

During his London years, Sargent moved in prominent artistic and literary circles. He maintained friendships with fellow artists like Claude Monet and was a respected, if somewhat aloof, figure in the London art scene, which included contemporaries like Whistler and Walter Sickert. His success was immense, his fees were high, and he became arguably the most sought-after portrait painter in the world.

Beyond the Constraints: Watercolors, Travels, and Murals

Despite his phenomenal success, by the early 1900s, Sargent began to grow weary of the demands and constraints of formal portraiture. He famously declared in 1907 that he would paint "no more mugs!" While he never entirely abandoned portraiture, especially charcoal sketches which he could complete quickly, he increasingly turned his attention to other genres that offered greater artistic freedom: watercolor landscapes and ambitious mural projects.

His travels provided constant inspiration for his watercolors. Sargent was an inveterate traveler throughout his life, and his later journeys focused on locations that allowed him to explore effects of light and color in landscape and architectural subjects. Venice remained a favorite destination; his Venetian watercolors capture the shimmering reflections in canals, the play of sunlight on ancient facades, and the bustling life of the city with extraordinary fluidity and transparency. He painted gondoliers, quiet side canals, and grand vistas with equal brilliance.

He also made numerous trips to the Alps, particularly in Switzerland and the Austrian Tyrol, painting mountain landscapes, glaciers, streams, and rustic scenes. These works often feature bold compositions and a vibrant palette, capturing the intense light and atmosphere of the high altitudes. Other travels took him back to Spain, where he continued to study Velázquez and was perhaps influenced by the light-filled canvases of contemporary Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla. He also journeyed to the Middle East (Palestine and Syria) and North Africa, producing sketches and watercolors of Bedouin figures, desert landscapes, and ancient ruins.

Sargent's watercolors are characterized by their spontaneity, technical mastery, and luminous quality. He used the medium with remarkable freedom, employing wet-on-wet techniques, bold washes, and opaque white highlights to achieve dazzling effects of light and atmosphere. These works were often painted for his own pleasure or for friends, rather than for public exhibition, and they reveal a more personal and experimental side of his art. Today, his watercolors are considered among the finest examples of the medium ever produced.

Concurrent with his shift towards landscape and watercolor, Sargent embarked on major mural commissions, primarily in Boston. In 1890, he was commissioned to decorate spaces in the newly constructed Boston Public Library. This massive project, titled "Triumph of Religion," occupied him intermittently for nearly three decades. It involved extensive research into religious history and symbolism, and the resulting murals, depicting complex allegories of Jewish and Christian history, are a departure from his usual style, showing influences from Byzantine mosaics and Renaissance frescoes. The project was ambitious but also controversial, particularly the panel depicting "Synagogue," which drew criticism from Boston's Jewish community.

He later undertook mural commissions for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (decorating the rotunda and staircases) and for Harvard University's Widener Library (commemorating Harvard students who died in World War I). These large-scale decorative projects allowed Sargent to explore historical and allegorical themes on a grand scale, demonstrating his versatility and his deep engagement with art history. They contrast sharply with the immediacy of his portraits and watercolors, showcasing a more formal, symbolic aspect of his artistic vision, influenced perhaps by contemporary muralists like the Frenchman Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.

World War I, Later Life, and Enduring Legacy

The outbreak of World War I significantly impacted Sargent's later years. Although he was in his sixties and living in London, he was commissioned by the British government's Ministry of Information in 1918 to create paintings documenting the war effort, serving as an official war artist. He traveled to the Western Front in France, witnessing the realities of modern warfare firsthand.

This experience resulted in several powerful works, most notably the monumental painting Gassed (1919). Measuring over 20 feet long, it depicts a line of soldiers blinded by a mustard gas attack being led to a dressing station, while others lie stricken on the ground. The painting is a harrowing yet strangely serene portrayal of the suffering and camaraderie of war, rendered with a classical sense of composition and a muted palette. It stands as one of the most iconic images of World War I and a testament to Sargent's ability to tackle somber, large-scale subjects far removed from the glamour of his society portraits. He also painted other war scenes and portraits of military leaders.

In his final years, Sargent continued to travel and paint watercolors, finding solace and inspiration in landscape. He undertook fewer oil portraits, though notable late examples like the formal Henry, Viscount Lascelles (1925) show his technical powers remained undiminished. He also completed his mural cycles in Boston. He remained a revered figure in the art world, though the rise of Modernist movements like Cubism and Fauvism began to make his style seem less cutting-edge to some critics.

Sargent maintained important friendships, notably with the novelist Henry James, who deeply admired Sargent's work and wrote perceptively about his art. Their friendship exemplified the close ties between the literary and artistic worlds of the era. Another key relationship was with Isabella Stewart Gardner, the eccentric Boston art collector, who was a major patron and friend, commissioning portraits and acquiring numerous works for her museum, Fenway Court. His friendships also extended to fellow artists, including a long-standing connection with Claude Monet, whom Sargent painted working outdoors.

John Singer Sargent died suddenly in his sleep from heart disease in London on April 14, 1925, at the age of 69. He was preparing to travel back to Boston regarding his murals. Memorial exhibitions were held in Boston, London, and New York, confirming his status as a major figure in Western art.

Artistic Style and Technique Summarized

Sargent's style is often described as a synthesis of Realism and Impressionism, grounded in the techniques of the Old Masters, particularly Velázquez and Hals. His hallmark was his dazzling technical proficiency, especially his bravura brushwork. He often painted alla prima, applying paint directly and decisively, creating surfaces that are vibrant and textured yet remarkably descriptive.

His handling of light was exceptional. Whether capturing the subtle indoor lighting of a drawing-room, the dappled sunlight of a garden, or the intense glare of the desert, he rendered light effects with uncanny accuracy and sensitivity. His palette could range from the restrained, tonal harmonies influenced by Velázquez and Whistler to the brighter, more broken color associated with Impressionism, particularly in his landscapes and watercolors.

Compositionally, Sargent often employed dynamic or unconventional arrangements, using cropping, diagonals, and dramatic poses to create visual interest and enhance the psychological impact of his portraits. He excelled at rendering textures – the sheen of satin, the softness of velvet, the sparkle of jewels – but this virtuosity always served the larger purpose of conveying the sitter's presence and character.

While associated with Impressionism due to his interest in light and occasional broken brushwork, Sargent remained fundamentally a realist, focused on accurate representation and strong draftsmanship. Unlike core Impressionists like Monet or Pissarro, he rarely dissolved form completely into light and color. His primary aim, especially in portraiture, was to capture the individual identity and social context of his subjects, often revealing subtle psychological nuances beneath the polished surfaces.

Critical Reception and Lasting Influence

During his lifetime, Sargent enjoyed immense fame and commercial success, particularly from the 1890s through the early 1900s. He was hailed as the leading portrait painter of his generation. However, with the rise of Modernism in the early twentieth century, his reputation began to decline among progressive critics. Figures like Roger Fry, a prominent British critic and proponent of Post-Impressionism, dismissed Sargent's work as brilliant but superficial, lacking in significant form and emotional depth, merely catering to the vanity of the wealthy. For several decades after his death, Sargent was often regarded as a talented but ultimately conservative painter, out of step with the major artistic innovations of the twentieth century.

This view began to change in the latter half of the twentieth century. A critical reassessment led by scholars and major museum exhibitions highlighted his extraordinary technical skill, his sophisticated understanding of art history, and the enduring appeal of his work. Critics began to appreciate the psychological acuity of his portraits and the sheer beauty and technical brilliance of his watercolors and landscapes.

Today, John Singer Sargent is firmly re-established as a major figure in American and European art history. He is recognized as a master technician, a brilliant observer of his time, and an artist who successfully navigated the complex currents of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century art. His portraits remain iconic representations of the Gilded Age elite, capturing an era of opulence, confidence, and transatlantic connection. His watercolors are celebrated for their freshness and virtuosity, and his murals are acknowledged for their ambition and intellectual depth. While the criticism of occasional superficiality persists in some quarters, his ability to create compelling, beautiful, and insightful images ensures his enduring popularity with both the public and art historians. He remains a towering figure, a bridge between tradition and modernity, whose dazzling brush continues to captivate viewers.