An Introduction to Elegance

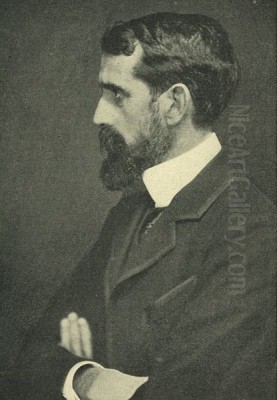

Paul César Helleu, born in Vannes, Brittany, on December 17, 1859, and passing away in Paris on March 23, 1927, stands as a quintessential French artist of the Belle Époque. His name evokes images of shimmering elegance, capturing the fleeting grace of high society women in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Paris and beyond. Primarily celebrated as a painter and an exceptionally gifted master of drypoint etching, Helleu developed a distinctive style characterized by fluid lines, delicate observations, and an unerring sense of chic.

His art provides a luminous window into an era defined by optimism, cultural effervescence, and a particular aesthetic sensibility. While Impressionism was revolutionizing the depiction of light and modern life, Helleu carved his own niche, focusing on the refined world of the aristocracy and the affluent bourgeoisie. His portraits and etchings became synonymous with the fashionable ideal of the time, sought after by collectors and sitters alike, both in his native France and internationally, particularly in Britain and the United States.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Helleu's journey began in the coastal region of Brittany. His father served as a customs inspector. A significant shadow fell over his youth with the early death of his mother while he was still in his teens, an event that undoubtedly left a lasting emotional imprint. Despite familial expectations potentially leaning elsewhere, the young Helleu felt the pull of art. This led him to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world.

Against his guardian's wishes, he pursued his passion, eventually gaining admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His time there, likely beginning in the mid-1870s, exposed him to academic traditions but also, crucially, to the ferment of new artistic ideas swirling through the city. He encountered the works of the Impressionists, absorbing their lessons on light and contemporary subject matter, even though his own path would diverge stylistically. Early years were marked by financial struggle, a common narrative for aspiring artists, but his talent and determination began to attract attention.

A Circle of Influence: Friendships and Mentorship

Helleu's artistic development and social ascent were significantly shaped by his connections within the vibrant art community. He cultivated deep and lasting friendships with some of the most prominent figures of his time. Perhaps the most significant was his bond with the American expatriate painter John Singer Sargent. Their friendship was one of mutual admiration and support; they frequently traveled together, sketched side-by-side, and even depicted each other in their works, leaving behind intimate records of their camaraderie.

Through Sargent, Helleu met James Jacques Tissot, another artist who had found success depicting elegant society. Tissot's own mastery of etching, particularly drypoint, proved revelatory for Helleu. Seeing Tissot's work is often cited as the catalyst that inspired Helleu to seriously explore the medium that would become central to his fame. The delicate, yet incisive lines possible with drypoint perfectly suited Helleu's aesthetic inclinations.

His circle also included the iconic Impressionist Claude Monet, with whom he shared a friendship, reflecting the interconnectedness of the Parisian art scene. James McNeill Whistler, another American expatriate known for his refined aestheticism and printmaking, was also a friend and likely an influence on Helleu's pursuit of elegance and subtle harmonies. Helleu's sensitivity to line and atmosphere resonated with Whistler's own artistic principles.

Furthermore, Helleu enjoyed a close association with the Italian portraitist Giovanni Boldini, known for his flamboyant and dynamic depictions of society figures. Boldini acted as something of a mentor, and while their styles differed – Boldini's being more overtly energetic, Helleu's more restrained and delicate – they shared a focus on capturing the essence of modern elegance. The influence of Edgar Degas, a master of line and observation of modern life, can also be discerned in Helleu's work, particularly in his ability to capture seemingly spontaneous moments and gestures.

His connections extended beyond painters. He was friends with the sculptor Auguste Rodin and the writer Marcel Proust. Proust, a keen observer of the social milieu Helleu depicted, famously based the character of the artist Elstir in his monumental novel À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time) partly on Helleu, immortalizing his friend's persona and artistic sensibility in literature. Helleu also moved in circles that included figures like the dandy and art patron Robert de Montesquiou, who facilitated introductions to potential sitters, including the renowned Countess Greffulhe. Contemporaries like the painter and printmaker Jean-Louis Forain, also known for his depictions of Parisian life, were part of this milieu. Critics, seeking historical parallels for his grace, often compared Helleu's work to that of 18th-century French masters like Antoine Watteau and Nicolas Lancret, highlighting a perceived lineage of French elegance.

The Master of the Drypoint Needle

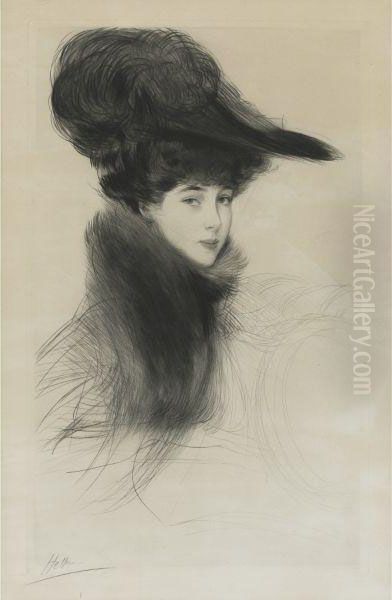

While Helleu worked proficiently in oils and pastels, his most distinctive contribution and widest fame came through his mastery of drypoint etching. This intaglio printmaking technique involves scratching an image directly into a copper plate using a sharp needle, often diamond-tipped in Helleu's case. Unlike engraving, drypoint doesn't remove the metal cleanly; instead, the needle raises a rough ridge of displaced metal called the "burr" alongside the incised line.

When the plate is inked, the burr traps additional ink, resulting in a characteristic soft, velvety, and slightly blurred line in the final print. This effect lent itself perfectly to Helleu's subjects – the delicate textures of hair, the shimmer of fabric, the subtle nuances of expression. The technique allowed for a sense of immediacy and spontaneity, akin to drawing, which suited Helleu's fluid style.

He became exceptionally prolific in this medium, producing over 2,000 drypoint etchings throughout his career. These prints were highly sought after, offering a more accessible way for admirers to own a piece of Helleu's art compared to his unique paintings or pastels. His drypoints often featured elegant women, children, and intimate domestic scenes, rendered with remarkable virtuosity and charm. He frequently experimented with printing in different colored inks, adding another layer of subtlety to his work. His success with drypoint cemented his reputation as a leading graphic artist of his generation.

Portraits of the Belle Époque

Helleu's name is inextricably linked with the portraiture of the Belle Époque. He became the favored artist for depicting the era's fashionable elite, particularly its women. His portraits are characterized by an air of effortless grace, sophistication, and modernity. He moved away from the stiff formality often seen in earlier Victorian portraiture, instead capturing his sitters in more relaxed, natural poses – reading, reclining, adjusting a hat, or interacting gently with a pet, as seen in works like Élégante de Chien Faisant le Beau.

His style emphasized flowing, calligraphic lines and a selective focus on detail. He often used a limited palette, relying on the expressiveness of his drawing and subtle tonal variations, particularly in his pastels and drypoints. Works like Femme en profil avec un chapeau (Woman in Profile with a Hat) or Élégante à la veste de fourrure (Elegant Woman in a Fur Jacket, 1896) exemplify his ability to convey chic and personality through line and silhouette.

He painted and etched some of the most prominent figures of the age, including the famously elegant Countess Élisabeth Greffulhe (a key inspiration for Proust's Duchesse de Guermantes) and Consuelo Vanderbilt, Duchess of Marlborough. These commissions placed him at the heart of transatlantic high society. His portraits were not just likenesses; they were distillations of an ideal, capturing the poise, fashion, and leisured lifestyle that defined the upper echelons of society during this gilded age. His work became a visual shorthand for Belle Époque elegance.

Alice Helleu: Muse and Lifelong Subject

Central to both Helleu's life and art was his wife, Alice Guérin. They married in 1886, and Alice quickly became his primary muse and the subject of countless works. Slender, graceful, and possessing a distinctive beauty, she embodied the Helleu aesthetic. He depicted her in numerous paintings, pastels, and drypoints, capturing her in intimate domestic settings, aboard their yacht, reading, arranging flowers, or simply gazing thoughtfully.

These portraits of Alice are among his most personal and celebrated works. They convey a palpable sense of affection and admiration. Unlike commissioned portraits, these works often possess a greater informality and tenderness, offering glimpses into the couple's life together. Specific works like the Portrait of Alice Guérin held in the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne, or the many pieces simply titled Portrait of Madame Helleu, showcase her distinctive features and poise.

Even works with more descriptive titles, sometimes rendered simply as depicting Madame Helleu engaged in an activity like adjusting her clothing or corsage (perhaps related to the cited Madame Helleu avec couche de maman), highlight her constant presence in his artistic vision. Alice was not merely a passive model; she was an active participant in the image Helleu projected of Belle Époque femininity. Together, they raised four children, and family life occasionally surfaced as a theme in his art, always rendered with his characteristic grace.

Beyond the Salon: Landscapes and Seascapes

While best known for his portraits of elegant women, Helleu's artistic interests were broader. He possessed a genuine love for the sea, likely stemming from his Breton origins and his passion for yachting. This translated into numerous seascapes and depictions of life aboard sailboats. These works often feature his wife and children, combining his interest in marine subjects with intimate family moments. They showcase his ability to capture the play of light on water and the dynamic forms of sails and rigging.

He also produced sensitive landscapes, often depicting parks or gardens, sometimes featuring figures enjoying leisure activities. Furthermore, Helleu was drawn to the grandeur of architecture, creating impressive studies of cathedral interiors, notably those of Rouen Cathedral, a subject also famously explored by his friend Monet. Still life subjects also appear in his oeuvre, though less frequently. These varied subjects demonstrate a wider artistic curiosity beyond the confines of the society portrait, revealing his skill in capturing different moods, textures, and light effects.

A Celestial Ceiling: The Grand Central Commission

One of Helleu's most ambitious and publicly visible projects took him across the Atlantic. In 1912, he was commissioned by the architects Whitney Warren and Charles Wetmore, whom he knew socially, to design the vast ceiling mural for the main concourse of the newly built Grand Central Terminal in New York City. This was a significant departure from his usual easel-sized works and etchings.

Helleu conceived a magnificent depiction of the Mediterranean night sky during the winter, stretching across the barrel-vaulted ceiling. The mural featured constellations and signs of the zodiac, painted in gold leaf against a cerulean blue background. He collaborated with astronomers from Columbia University to ensure a degree of accuracy, although artistic license was taken, notably reversing the sky as if viewed from above (a mistake that generated some contemporary comment).

The sheer scale and prominent location of the "Sky Ceiling" made it one of his most famous achievements, introducing his aesthetic to a vast public audience. Ironically, years of grime and alterations led to the ceiling being obscured or painted over. However, a major restoration project in the 1990s brought Helleu's celestial vision back to its former glory, allowing contemporary visitors to marvel at this unique aspect of his artistic legacy.

Recognition, Legacy, and Final Years

Helleu achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His work was exhibited widely in Paris, London, and New York, and eagerly collected on both sides of the Atlantic. His elegant style perfectly captured the zeitgeist of the Belle Époque, making him a sought-after artist among the social elite. Formal recognition came in 1904 when he was awarded the prestigious Légion d'honneur by the French government, acknowledging his significant contributions to the arts.

However, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a turning point, shattering the optimism and social structures of the Belle Époque. In the post-war era, artistic tastes shifted dramatically towards Modernism, embracing avant-garde movements like Cubism, Surrealism, and abstraction. Helleu's refined, representational style began to seem dated to some, and his popularity waned compared to its pre-war peak.

Despite this shift in fashion, he continued to work. He passed away in Paris in 1927 at the age of 67, following complications from surgery (peritonitis). While his fame may have dimmed in the mid-20th century, subsequent reappraisals have reaffirmed his importance as a master draftsman, a brilliant etcher, and a sensitive chronicler of a specific time and social stratum.

Enduring Elegance

Paul César Helleu occupies a unique place in the history of French art. He was not a revolutionary in the mold of the Impressionists or the later Modernists, but he possessed a singular talent for capturing the ephemeral grace and refined aesthetics of the Belle Époque. His mastery of the drypoint technique allowed him to translate his fluid drawing style into prints of remarkable delicacy and charm.

Through his countless portraits, particularly those of his wife Alice and the leading women of society, he created an enduring visual record of an era defined by elegance, luxury, and a certain joie de vivre. His work continues to fascinate for its technical brilliance, its intimate portrayal of his subjects, and its evocative power in summoning the spirit of a bygone age. The graceful line of Helleu remains a testament to his distinctive artistic vision and his role as a premier interpreter of Belle Époque sophistication.