John Thomson (1837-1921) stands as a monumental figure in the history of photography, a Scottish pioneer whose lens captured the essence of diverse cultures and societies at a pivotal moment of global change. More than just a photographer, Thomson was an intrepid explorer, a keen geographer, and a perceptive social commentator. His extensive travels across the Far East and his later work in London produced an invaluable visual archive, offering unprecedented insights into worlds largely unknown to the West. His work not only documented landscapes and peoples but also laid foundational stones for the burgeoning fields of photojournalism and social documentary photography, leaving an indelible mark on how we perceive and record the human condition.

Early Life and Photographic Awakening

Born in Edinburgh on June 14, 1837, into a family of tobacco merchants, John Thomson's early life did not immediately suggest a future in the nascent art of photography. However, his formative years were marked by a practical and intellectual curiosity. He undertook an apprenticeship at an optical instrument manufacturing firm, a role that would have provided him with a fundamental understanding of lenses and the mechanics of image-making. This technical grounding was complemented by evening art classes, suggesting an early inclination towards visual representation and aesthetic principles.

The 1850s and early 1860s were a period of rapid advancement in photographic technology. The wet-collodion process, though cumbersome, offered unparalleled detail and reproducibility, and it was this challenging medium that Thomson would master. His decision in 1862 to travel to Singapore with his brother William, a watchmaker and photographer, marked a definitive turn. This voyage was not merely a colonial adventure but the beginning of a decade-long odyssey that would see Thomson establish himself as one of the foremost travel photographers of his era.

Photographic Expeditions in the Far East

Thomson's arrival in Asia coincided with a period of intense Western interest in the region, yet reliable visual information was scarce. Photography offered a powerful tool to bridge this gap, and Thomson seized the opportunity with remarkable skill and sensitivity. His initial base in Singapore served as a springboard for extensive photographic journeys. He ventured into Malaya (present-day Malaysia), Sumatra, and other parts of what is now Indonesia, meticulously documenting the diverse landscapes, local rulers, indigenous populations, and burgeoning colonial settlements.

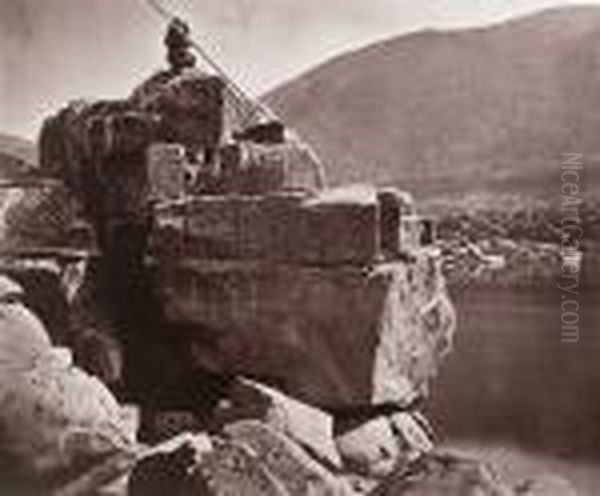

His travels also took him to Siam (Thailand), where he had the distinct honor of photographing King Mongkut (Rama IV) and his court, a testament to his growing reputation and diplomatic skill. He further explored parts of India and Indochina, including Cambodia, where he captured some of the earliest and most striking images of the ancient ruins of Angkor Wat. Throughout these expeditions, Thomson was not merely a passive observer; he was an active ethnographer, often taking detailed notes to accompany his images, providing context and depth to his visual records.

Hong Kong and the Photographic Documentation of China

In 1867, John Thomson established a professional presence in Hong Kong, opening the J. Thomson photographic studio. Two years later, he relocated his studio to a more prominent position within the premises of Lane Crawford & Meters on Queen's Road. Hong Kong, a bustling entrepôt and a nexus of East-West interaction, provided a rich environment for his work. He photographed the colonial architecture, the vibrant street scenes, and the diverse populace of the island.

However, it was his extensive work in mainland China between 1870 and 1872 that would cement his international reputation. Thomson embarked on ambitious journeys, navigating challenging terrains and complex social landscapes. He traveled up the Min River in Fujian province, ventured to Amoy (Xiamen), Formosa (Taiwan), Swatow (Shantou), and Canton (Guangzhou). His expeditions also took him to the northern cities, including Peking (Beijing), where he photographed the Imperial Palace, the Great Wall, and portraits of high-ranking Manchu officials and ordinary citizens alike. He was one of the first Western photographers to gain such extensive access and to document such a wide array of Chinese life.

Major Works: Illuminating China and London

John Thomson's most significant contributions to the photographic canon are arguably his published volumes, which brought his meticulous fieldwork to a wider audience.

Illustrations of China and Its People

Published in four volumes between 1873 and 1874, Illustrations of China and Its People was a landmark achievement. Comprising 218 of Thomson's photographs, accompanied by his own descriptive text, this monumental work offered Western audiences an unprecedented and remarkably nuanced view of Chinese society, culture, and geography. The images ranged from grand imperial portraits and architectural studies to intimate scenes of daily life, street vendors, laborers, and diverse ethnic groups. Thomson's approach was largely respectful, aiming to present an authentic portrayal, though inevitably viewed through the lens of a 19th-century European. This publication was a significant ethnographic and historical document, shaping Western perceptions of China for generations.

Street Life in London

Upon his return to Britain, Thomson turned his lens towards his own society, collaborating with the radical journalist Adolphe Smith. Between 1876 and 1877, they produced Street Life in London, a monthly publication featuring Thomson's photographs and Smith's accompanying essays. This work is widely regarded as a pioneering example of social documentary photography. Thomson's images captured the harsh realities of life for London's urban poor – the street vendors, cabmen, flower sellers, and crossing sweepers. These photographs were not merely picturesque; they were imbued with a sense of empathy and a desire to shed light on social inequalities. Street Life in London demonstrated the power of photography as a tool for social commentary and reform, influencing subsequent generations of documentary photographers.

Photographic Style and Technical Mastery

John Thomson's photographic output is characterized by its exceptional technical quality and thoughtful composition. He primarily used the wet-collodion process, a demanding technique that required the glass plate negative to be coated, sensitized, exposed, and developed while still wet, often under challenging field conditions. This process, however, yielded negatives capable of producing incredibly detailed and tonally rich prints. Thomson's mastery of this technique, even in the humid climates of Southeast Asia or the bustling streets of London, was remarkable.

His compositional skills were equally impressive. Thomson possessed a painterly eye, carefully arranging elements within the frame to create balanced and engaging images. Whether photographing a sweeping landscape, an architectural marvel, or an intimate portrait, his images often exhibit a strong narrative quality. He understood the interplay of light and shadow, using it to model form and create atmosphere.

Furthermore, Thomson's approach to his subjects, particularly in his portraiture, often displayed a remarkable degree of humanism. While the conventions of 19th-century ethnographic photography could sometimes be objectifying, Thomson frequently managed to capture a sense of individual dignity and personality in his sitters, whether they were Manchu nobles or London street sweepers. This sensitivity, combined with his technical prowess and artistic vision, elevated his work beyond mere record-keeping.

A Pioneer of Social Documentary and Photojournalism

John Thomson's contributions extend beyond travel and ethnographic photography. His work, particularly Street Life in London, positions him as a crucial forerunner of social documentary photography and photojournalism. By systematically documenting the lives of London's marginalized communities, he used photography as a means of social investigation and advocacy. This approach, which combined visual evidence with textual narrative to highlight social issues, was groundbreaking for its time.

His images provided a visual testimony that was more immediate and arguably more impactful than written accounts alone. They challenged prevailing Victorian sensibilities and brought the realities of poverty to the attention of a wider, more affluent public. In this sense, Thomson's work prefigures the efforts of later social reformers and photographers like Jacob Riis in New York, who used the camera to expose urban squalor and advocate for change, or Lewis Hine, whose photographs of child labor were instrumental in legislative reforms in the United States.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

John Thomson's legacy is multifaceted. His photographs from the Far East remain an invaluable historical and anthropological resource, offering a unique window into societies undergoing profound transformations. They are studied by historians, anthropologists, and art historians for their rich detail and cultural insights. His work helped to shape Western visual understanding of Asia in the late 19th century, and continues to inform contemporary discussions about colonialism, representation, and cross-cultural encounters.

In the realm of photographic practice, Thomson's commitment to quality, his innovative use of photography for social commentary, and his ability to blend artistic sensibility with documentary intent set a high standard. He demonstrated the versatility of the medium, pushing its boundaries beyond portraiture and picturesque views. His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent generations of photographers who sought to explore the world, document social conditions, and tell compelling visual stories. Photographers like Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and later, members of the Magnum Photos agency, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson or Robert Capa, owe a debt to pioneers like Thomson who established the power and potential of documentary photography.

After his active photographic career, Thomson continued to contribute to the field. He became an instructor in photography to explorers at the Royal Geographical Society in London from 1886, sharing his extensive knowledge and experience. He was appointed photographer to the British Royal Family in 1910 by Queen Victoria. John Thomson passed away on September 29, 1921, leaving behind a rich and diverse body of work that continues to resonate today.

Distinguishing John Thomson the Photographer from Contemporaries

It is important, particularly given the information provided in the initial query, to distinguish John Thomson, the Scottish photographer (1837-1921), from other notable individuals, particularly those in the arts or with similar names, to avoid historical confusion.

Tom Thomson: The Canadian Painter

One such figure is Tom Thomson (1877-1917), a highly influential Canadian painter. Tom Thomson, no relation to John Thomson the photographer, was a pivotal figure in the development of a distinctively Canadian school of landscape painting in the early 20th century. His vibrant, expressive depictions of the Ontario wilderness, particularly Algonquin Park, had a profound impact on a group of artists who would later form the iconic "Group of Seven."

Tom Thomson's life was tragically cut short in 1917, but his artistic vision and passionate engagement with the Canadian landscape inspired artists like Lawren Harris, J.E.H. MacDonald, A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, Franklin Carmichael, and Frank Johnston (later joined by A.J. Casson, Edwin Holgate, and L.L. FitzGerald). These painters sought to create a national art form, breaking away from European traditions to capture the unique character and rugged beauty of Canada. Tom Thomson is often considered a spiritual guide or precursor to the Group of Seven, even though he died before its official formation in 1920. His work shares a spirit of exploration and a deep connection to place, much like John Thomson the photographer, but his medium and artistic milieu were entirely different.

The source material mentions a "John Thomson" possibly receiving art instruction from William Cruikshank (a Toronto-based artist and teacher who did instruct some Group of Seven members) in 1906 and meeting Lawren Harris in 1911. These references almost certainly pertain to Tom Thomson, the Canadian painter, not John Thomson the photographer, who by this time was well-established in London and in his late 60s or early 70s. The Group of Seven, and Tom Thomson by extension, were contemporaries of later modernist movements in Europe, such as Fauvism led by Henri Matisse or Cubism pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, though their focus remained distinctly Canadian. One might also consider the work of their Canadian contemporary Emily Carr, who similarly focused on the Canadian landscape and Indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest.

Other Potential Confusions: The Aviation Pioneer

The source material also alludes to a "John Thomson" who was an aviation pioneer, designing gliders and aircraft, and even establishing a private airport and museum. This refers to a different individual entirely, likely John W. Thomson (often "Johnny" Thomson), an American figure associated with early aviation in the 20th century, or perhaps another individual with a similar name involved in aeronautics. This person's endeavors in flight, while fascinating, are distinct from the life and work of John Thomson, the 19th-century Scottish photographer. Such coincidences in names across different fields and eras can sometimes lead to conflated biographies if not carefully examined.

Conclusion: A Lasting Vision

John Thomson (1837-1921) was a figure of remarkable energy, skill, and foresight. His photographic journeys into the heart of Asia provided the West with some of its most enduring and insightful images of the region during a critical period of transition. His later work in London demonstrated a profound social conscience, establishing him as a key progenitor of documentary photography. He navigated the technical challenges of early photography with mastery, creating images that were not only informative but also possessed considerable aesthetic merit.

His legacy is preserved in the thousands of negatives and prints held in collections worldwide, and in the influential publications that disseminated his work. As an art historian, one recognizes in Thomson a pivotal figure who understood and harnessed the unique power of photography to explore, document, and interpret the world. He was more than a taker of pictures; he was a visual historian, an ethnographer, and an artist whose work continues to inform and inspire, securing his place as one of the most important photographers of the 19th century. His dedication to capturing the human experience, whether in the imperial courts of Siam, the bustling streets of Canton, or the impoverished alleys of London, provides a timeless testament to the power of the photographic image.