John Trumbull stands as a monumental figure in the annals of American art, an artist whose life and work were inextricably intertwined with the birth and early years of the United States. Born into a prominent Connecticut family on the cusp of revolution, Trumbull was uniquely positioned to witness and participate in the foundational events of his nation. His ambition was not merely to paint, but to create a lasting visual record of the American Revolution, to immortalize its heroes, its sacrifices, and its triumphs for posterity. As a soldier, a diplomat, and above all, an artist, Trumbull dedicated much of his career to this grand historical project, producing iconic images that have shaped America's collective memory of its origins. His paintings, particularly those depicting pivotal moments of the war and the establishment of the new government, are more than just artistic achievements; they are historical documents in their own right, imbued with the patriotic fervor and neoclassical ideals of his time.

Early Life and Stirrings of Ambition

John Trumbull was born on June 6, 1756, in Lebanon, Connecticut. His father, Jonathan Trumbull, was the Governor of Connecticut, a position of considerable influence, especially during the tumultuous years leading up to and during the Revolution. His mother, Faith Robinson Trumbull, was a descendant of the prominent Robinson family. This lineage placed young John in a household where matters of governance, colonial rights, and eventually, independence, were daily topics of discussion. Such an environment undoubtedly instilled in him a deep sense of patriotism and an awareness of the historical significance of the times.

A childhood accident had a profound impact on Trumbull's life and, arguably, his art. At the age of five, he fell down a flight of stairs, severely injuring his left eye and resulting in the near-total loss of vision in that eye. This monocular vision might have influenced his perception of depth and his meticulous attention to detail in his later, often small-scale, historical compositions. Despite this physical challenge, he demonstrated an early aptitude for drawing and a keen intellect.

Trumbull entered Harvard College in 1771 at the young age of fifteen, graduating in 1773. His education at Harvard was classical, focusing on literature, mathematics, and languages, rather than formal art training, which was virtually non-existent in the American colonies at the time. However, during his college years, he reportedly studied engravings of works by European masters and visited the studio of John Singleton Copley in Boston, a leading portraitist in colonial America. Copley's sophisticated technique and ability to capture the character of his sitters would have been an early, significant artistic exposure for Trumbull.

The Revolutionary War: Soldier and Witness

With the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, John Trumbull's patriotic fervor led him to join the Continental Army. His skills in drawing and map-making proved valuable. He witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill from Roxbury, an experience that would later fuel one of his most dramatic paintings. His abilities caught the attention of General George Washington, and in August 1775, Trumbull was appointed as an aide-de-camp to the Commander-in-Chief, with the rank of colonel.

His service included creating detailed plans of enemy fortifications, particularly during the siege of Boston. He later served as a deputy adjutant-general under General Horatio Gates. However, a dispute over the date of his commission led to his resignation from the army in February 1777. Though his active military career was relatively brief, his firsthand experiences of the war, its key figures, and its dramatic events provided him with invaluable source material and a profound understanding that would inform his life's work as a historical painter. He had seen the courage, the sacrifice, and the gravity of the struggle for independence, and he felt a calling to preserve these moments.

Following his resignation, Trumbull initially struggled to find his path. He briefly considered a legal career but his passion for art, nurtured by his early encounters with Copley's work and his own innate talent, ultimately won out. He recognized that America lacked a tradition of grand historical painting, and he envisioned himself filling that void, becoming the visual chronicler of the nation's birth.

Artistic Apprenticeship in London

To pursue serious artistic training, Trumbull knew he had to go to Europe. In late 1780, with the war still raging, he sailed for London. His destination was the studio of Benjamin West, an American-born painter who had achieved immense success in England, becoming historical painter to King George III and a co-founder, later president, of the Royal Academy of Arts. West's studio was a welcoming place for aspiring American artists, including Gilbert Stuart, who would become a lifelong friend and sometimes rival of Trumbull, and later, painters like Washington Allston and Samuel F.B. Morse.

Under West's tutelage, Trumbull honed his skills in drawing, composition, and oil painting. West was a proponent of neoclassical history painting, which emphasized heroic subjects, clear narratives, and idealized forms, often drawn from classical antiquity or recent historical events. He famously broke with tradition by depicting contemporary figures in modern dress in his painting The Death of General Wolfe (1770), a work that greatly influenced Trumbull's approach to his American Revolution series.

Trumbull's time in London was dramatically interrupted. In November 1780, following news of the capture and execution of Major John André as a spy in America (an event in which Trumbull's own correspondence had been, however innocently, implicated), Trumbull was arrested on suspicion of treason. He was imprisoned for seven months, a period of considerable anxiety. Benjamin West and other influential figures, including the statesman Edmund Burke, intervened on his behalf, eventually securing his release on the condition that he leave England. This experience, while harrowing, likely deepened his resolve and his American identity.

He briefly returned to America in 1782 but, recognizing the need for further study and the limited opportunities for ambitious history painting in the war-torn colonies, he went back to London in 1784 after peace was declared. He rejoined West's studio and began in earnest to plan his great series of paintings depicting the American Revolution.

The Grand Historical Project

Trumbull's ambition was monumental: to create a series of paintings that would narrate the key events of the American Revolution. He envisioned these works not just as art, but as patriotic statements, educational tools, and a means of fostering national unity and pride. He began with smaller-scale versions, intending to use them as models for larger canvases and as a basis for engravings that could be widely disseminated.

His approach was meticulous. He sought out individuals who had participated in the events he depicted, sketching them from life to ensure accuracy in their likenesses. This often involved extensive travel. For instance, when working on The Declaration of Independence, he traveled to Paris to portray Thomas Jefferson, who was then the American minister to France, and to secure likenesses of French officers who had served in the American war for other paintings. Jefferson became an important supporter and patron, offering advice and encouragement.

During this period in London and Paris (1784-1789), Trumbull produced some of his most celebrated early historical paintings. These works combined the grand manner of European history painting, influenced by West and the neoclassical ideals of artists like Jacques-Louis David, with a distinctly American subject matter and a commitment to historical veracity.

Masterpieces of the Revolution

Several paintings from this period stand out as cornerstones of Trumbull's achievement and as iconic images in American art.

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775 (completed 1786)

This painting captures the chaos and heroism of one of the earliest and bloodiest engagements of the war. Trumbull, having witnessed the battle's aftermath, imbued the scene with dramatic intensity. The central focus is the dying American General Joseph Warren, a figure of martyrdom, being defended by his compatriots. The composition is dynamic, with swirling smoke, clashing figures, and a sense of urgent movement. Trumbull carefully researched the uniforms and included portraits of many of the participants, both American and British, lending authenticity to the scene. The painting elevates a specific historical event to a universal statement about courage and sacrifice.

The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775 (completed 1786)

Similar in spirit and scale to the Bunker Hill painting, this work depicts another tragic loss for the American cause: the death of General Richard Montgomery during the ill-fated assault on Quebec. Again, Trumbull focuses on the heroic death of the leader, surrounded by his grieving soldiers. The dramatic lighting, reminiscent of Baroque masters like Caravaggio, and the emotional intensity of the figures make this a powerful image. Both this and the Bunker Hill painting were exhibited at Benjamin West's studio and received considerable acclaim, establishing Trumbull's reputation as a historical painter.

The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776 (first version completed c. 1787-1820)

Perhaps Trumbull's most famous work, The Declaration of Independence, depicts the presentation of the draft of the Declaration to the Continental Congress. Trumbull's goal was to commemorate this pivotal moment and to preserve the likenesses of the men who risked their lives to sign the document. He painstakingly sought out 42 of the 56 signers for life portraits, as well as some non-signers present. The composition is more static and formal than his battle scenes, reflecting the solemnity of the occasion. It is arranged like a frieze, with the drafting committee (Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston) presenting the document to John Hancock, the president of the Congress. The painting has become the definitive visual representation of this event, familiar to generations of Americans, partly due to its reproduction on the U.S. two-dollar bill.

The Capitol Rotunda Paintings

Trumbull's lifelong ambition culminated in a commission from the U.S. Congress in 1817 to produce four large-scale historical paintings for the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. This was a significant national project, and Trumbull was chosen over other contemporary artists like Rembrandt Peale, son of the famed Charles Willson Peale. For these monumental works, Trumbull drew upon his earlier, smaller versions. The four paintings, completed between 1817 and 1824, are:

The Declaration of Independence: A larger version of his earlier masterpiece.

The Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, October 17, 1777: Depicting a crucial American victory that helped secure French support for the Revolution.

The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, October 19, 1781: Illustrating the decisive battle that effectively ended the war.

General George Washington Resigning His Commission to Congress as Commander-in-Chief of the Army at Annapolis, Maryland, December 23, 1783: A scene symbolizing the triumph of republican ideals, as Washington voluntarily relinquishes power.

These paintings, each measuring twelve by eighteen feet, were installed in the Capitol Rotunda, where they remain today. While they have faced art historical criticism over the years for a certain stiffness or a perceived decline in artistic power compared to his smaller, earlier versions, they are undeniably powerful symbols of American nationhood and a testament to Trumbull's dedication to his vision. They cemented his status as the preeminent painter of the American Revolution.

Portraiture and Other Works

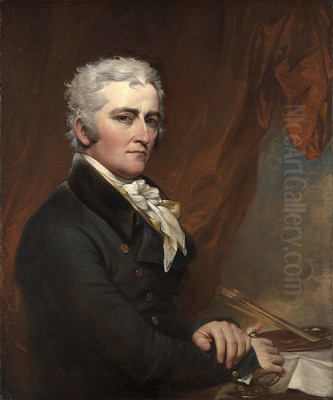

While best known for his historical scenes, John Trumbull was also a skilled portraitist. His need to capture accurate likenesses for his historical compositions meant he painted numerous individual portraits, often in miniature, of the leading figures of the era. These include multiple portraits of George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton.

His portraits, like his historical works, are generally in the neoclassical style, characterized by clarity, a degree of idealization, and a focus on conveying the sitter's character and public persona. His portrait of George Washington, for example, in Washington at Verplanck's Point (1790), depicts the general as a commanding and dignified leader. While perhaps not possessing the psychological depth of portraits by his contemporary Gilbert Stuart (whose "Athenaeum" portrait of Washington became iconic), Trumbull's portraits are valuable historical records and accomplished works of art. He also painted landscapes and some religious subjects, though these form a smaller part of his oeuvre.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Contemporaries

Trumbull's artistic style is firmly rooted in Neoclassicism, the dominant artistic movement of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This style, championed in France by Jacques-Louis David and in Britain by artists in Benjamin West's circle, emphasized order, clarity, didactic purpose, and subjects drawn from history or classical mythology. Trumbull adapted these principles to American subjects, infusing them with a patriotic spirit.

His primary influence was undoubtedly Benjamin West. West's encouragement, his technical instruction, and his example of depicting contemporary history in the grand manner were crucial to Trumbull's development. Trumbull also admired the work of earlier masters, particularly the great history painters of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, whose works he would have studied through engravings. The influence of British portraitists like Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first president of the Royal Academy, and Thomas Gainsborough can also be discerned in his approach to portraiture.

In America, his contemporaries included Charles Willson Peale, another artist-soldier who chronicled the Revolution, known for his portraits and his establishment of the Peale Museum in Philadelphia. Gilbert Stuart was a major figure, primarily a portraitist, whose fluid brushwork and insightful characterizations often contrasted with Trumbull's more linear and formal style. John Singleton Copley, after his move to London in 1774, also became a prominent history painter, and his work, such as Watson and the Shark or The Death of Major Peirson, would have been known to Trumbull. Other American artists of the period included Ralph Earl, known for his direct and somewhat austere portraits, and later figures like Thomas Sully and Washington Allston, who represented the transition towards Romanticism.

Later Life, Challenges, and Legacy

After his return to the United States in 1789, Trumbull spent several years in New York and Philadelphia, working on his paintings and portraits. He also served as a diplomat from 1794 to 1804 as secretary to John Jay during negotiations for the Jay Treaty in London, and later as a commissioner to settle claims. This period saw him travel between England and America.

In his later years, Trumbull faced financial difficulties and a sense that his artistic contributions were not always fully appreciated. He served as president of the American Academy of Fine Arts in New York from 1817 to 1836. However, his somewhat autocratic leadership style and conservative artistic views led to dissatisfaction among younger artists, including Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, who eventually broke away to form the National Academy of Design in 1825, with Samuel F.B. Morse as its first president. This was a blow to Trumbull's standing in the New York art world.

A crucial development in his later life was his arrangement with Yale College (now Yale University). In 1831, struggling financially, Trumbull offered his collection of paintings to Yale in exchange for an annuity of $1,000 for the rest of his life. Yale accepted, and the Trumbull Gallery, designed by the artist himself, was constructed on the Yale campus to house the collection. This was the first college-affiliated art museum in the United States and ensured the preservation of a significant body of his work. The core of this collection, including many of his iconic Revolutionary War paintings, is now housed in the Yale University Art Gallery.

John Trumbull died in New York City on November 10, 1843, at the age of 87. He was buried, alongside his wife Sarah Hope Harvey Trumbull (whom he married in 1800 and who predeceased him in 1824), beneath the Trumbull Gallery at Yale, as per his wishes. His remains were later moved to the crypt beneath the newer Yale University Art Gallery building.

Trumbull's Enduring Impact

John Trumbull's impact on American art and historical consciousness is undeniable. His paintings of the Revolution became, and in many ways remain, the definitive visual representations of these foundational events. They have been reproduced countless times in textbooks, popular histories, and commemorative materials, shaping how generations of Americans have envisioned their nation's origins.

His dedication to historical accuracy, particularly in capturing the likenesses of the participants, gives his work a documentary value that complements its artistic merit. He understood the power of art to shape memory and to foster a sense of national identity. While his style might seem formal or idealized to modern eyes, it was perfectly attuned to the neoclassical sensibilities of his era, which valued heroism, civic virtue, and the commemoration of great deeds.

Artists like Emanuel Leutze, with his famous Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), would later continue the tradition of American historical painting, though often with a more Romantic sensibility. Trumbull, however, remains the primary "Painter of the Revolution." His unique position as both a participant in and a chronicler of the era gave his work an authority and immediacy that few could match. His ambition to create a national epic in paint was largely realized, and his works continue to resonate as powerful expressions of America's founding ideals and struggles. Through his art, John Trumbull not only pictured a new nation but also helped to define its image for centuries to come.