Gilbert Stuart stands as one of the most significant figures in American art history, renowned primarily for his captivating portraits that defined the image of the nascent United States. His depictions of the nation's founding generation, particularly George Washington, have become iconic, shaping the visual identity of America's early leaders for posterity. Stuart's journey took him from colonial Rhode Island to the bustling art centers of London and Dublin, and finally back to the new republic he would help immortalize through his brush. His unique style, characterized by luminous flesh tones, fluid brushwork, and an uncanny ability to capture the sitter's character, set him apart and established a benchmark for American portraiture.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Gilbert Stuart was born on December 3, 1755, in Saunderstown, a village within North Kingstown, Rhode Island. He hailed from a modest background; his father, also named Gilbert Stuart, was a Scottish immigrant who operated the colonies' first snuff mill, a venture that ultimately proved unsuccessful. The family's financial instability prompted a move to the more prosperous town of Newport, Rhode Island, when young Gilbert was about six years old. Newport, a thriving colonial port city, offered a more stimulating environment, and it was here that Stuart's artistic inclinations began to surface.

Even as a boy, Stuart demonstrated a natural aptitude for drawing. His talent did not go unnoticed for long. Around the age of 13 or 14, he encountered Cosmo Alexander, a visiting Scottish painter of some repute. Alexander recognized the young man's potential and took him under his wing, providing Stuart with his first formal art instruction around 1769 or 1770. This mentorship was a crucial turning point, offering Stuart a pathway into the world of professional art.

Under Alexander's guidance, Stuart honed his skills. In 1771, seeking to further his pupil's education, Alexander took Stuart with him back to Scotland. The plan was for Stuart to continue his studies abroad, immersing himself in the European artistic tradition. However, this promising chapter was cut tragically short when Cosmo Alexander died unexpectedly in Edinburgh in 1772. Stuart, barely seventeen, found himself stranded, alone, and penniless in a foreign land.

The experience was harsh. Stuart struggled to support himself, facing poverty and desperation. His attempt to establish himself as a painter in Scotland failed amidst these difficult circumstances. Ultimately, he was forced to secure passage back to America in 1773, reportedly working his way across the Atlantic as a crew member on a coal ship. This difficult period undoubtedly shaped his resilient, if sometimes erratic, character. Back in Newport, he resumed painting, attempting to build a career based on the training he had received.

Seeking Fortune in London: The West Studio

The artistic opportunities in colonial Newport were limited, and the looming American Revolution further destabilized the region. Stuart, likely sensing limited prospects and perhaps seeking to avoid the conflict (his family had Loyalist leanings, though his own position was ambiguous), made a pivotal decision. In 1775, on the eve of the Revolution, he sailed for London, the vibrant heart of the British Empire and its art world.

Arriving in London, Stuart initially faced hardship once again. He struggled for about two years, living in relative obscurity and poverty. His fortunes changed dramatically when he sought out Benjamin West in 1777. West, an American expatriate from Pennsylvania, had achieved remarkable success in London, becoming a historical painter to King George III and a co-founder, later president, of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts. West's studio was a hub for aspiring artists, particularly those from America, including figures like John Trumbull and members of the Peale family, such as Charles Willson Peale, though Peale had studied with West earlier.

West generously took Stuart into his household and studio, first as an assistant and later as a valued pupil. This association was transformative. Stuart spent approximately five years under West's tutelage, absorbing invaluable lessons in technique, color theory, and composition. West's own work, often grand historical and religious scenes, exposed Stuart to the prevailing "Grand Manner" style, though Stuart would ultimately adapt its principles to the more intimate scale of portraiture. West's guidance provided Stuart with the technical foundation and professional connections he needed to launch his own career.

Breakthrough: The Skater and London Success

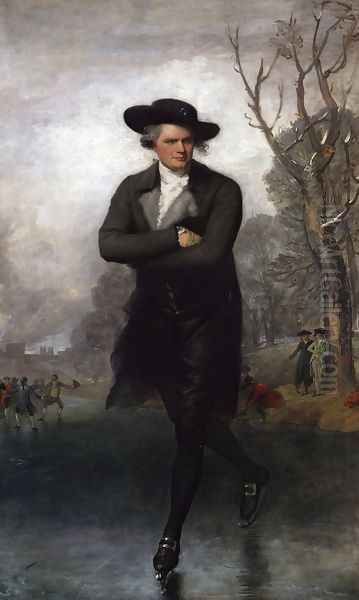

While working in West's studio, Stuart began exhibiting his own work at the Royal Academy. His breakthrough came in 1782 with the exhibition of The Skater, a full-length portrait of William Grant of Congalton. The painting was a sensation. Its dynamic pose, unconventional subject matter (a gentleman gracefully skating), and fluid, confident brushwork captured the attention of critics and the public alike. It deviated from the more staid conventions of portraiture common at the time and signaled the arrival of a fresh, distinctive talent.

The Skater effectively launched Stuart's independent career. Commissions began to pour in, and he quickly established himself as one of London's most fashionable portrait painters, rivaling established British masters like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough in popularity, if not always in critical esteem according to the strictest academic standards. He opened his own studio and began commanding high prices for his work. His portraits from this period exhibit a sophisticated elegance, characterized by silvery tones, delicate handling of fabrics, and an increasing focus on capturing the psychological presence of the sitter.

Stuart's London portraits often displayed the influence of the British school, particularly the fluid brushwork reminiscent of Gainsborough and the attention to social grace seen in Reynolds's work. However, Stuart was already developing his own signature approach, particularly in his treatment of faces. He preferred thinner paint application and subtle modeling, aiming for a sense of lifelike immediacy rather than heavily worked surfaces. He painted many prominent figures of the day, honing his skills and building his reputation.

Financial Shadows and the Irish Interlude

Despite his artistic success and substantial income, Stuart proved notoriously inept at managing his finances. He lived extravagantly, spending lavishly on clothes, entertaining, and maintaining a fashionable lifestyle. Consequently, he accumulated significant debts. His financial situation became increasingly precarious, mirroring a pattern that would plague him throughout his life. Facing mounting pressure from creditors, Stuart made another abrupt move.

In 1787, he hastily left London for Dublin, Ireland, essentially fleeing his debts. Ireland offered a fresh start and a less competitive art market. Stuart quickly replicated his London success in Dublin, becoming the city's leading portraitist. He painted numerous members of the Irish aristocracy and political elite, including figures like John FitzGibbon, the Lord Chancellor of Ireland. His Irish portraits continued to showcase his refined style and ability to capture likeness and character.

However, his financial habits did not change. Stuart continued to live beyond his means, and his debts began to mount once again in Ireland. He also reportedly engaged in unsuccessful investment schemes. After about five or six years in Dublin, his financial situation became untenable. Once again facing the threat of debtors' prison, Stuart looked for another escape. This time, his sights were set on returning to his native land, the newly formed United States of America.

Return to America: The Washington Quest

Stuart sailed from Dublin in 1793, arriving first in New York City. His primary motivation for returning to the United States was reportedly a singular, ambitious goal: to paint a portrait of George Washington. Washington, the hero of the Revolution and the first President of the United States, was the most revered figure in the nation. Stuart recognized that a successful portrait of Washington would not only be a patriotic endeavor but also the ultimate professional credential, securing his reputation and attracting commissions from the American elite.

After a brief period in New York, Stuart moved to Philadelphia in the winter of 1794-1795. Philadelphia was then the temporary capital of the United States and the center of its political and social life. Armed with a letter of introduction from John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the United States (whom Stuart had painted in London), Stuart finally secured sittings with President Washington in 1795.

Painting the President: Challenges and Triumphs

Painting Washington proved to be a unique challenge. Stuart, known for his witty conversation and ability to put sitters at ease to capture their natural expressions, found the president a difficult subject. Washington, burdened by the responsibilities of office and naturally reserved, presented a formal and somewhat stern demeanor during the sittings. Stuart later remarked on the difficulty of penetrating Washington's public mask to reveal the man beneath. He reportedly tried various conversational gambits, discussing topics like horses and farming, to elicit a more relaxed expression.

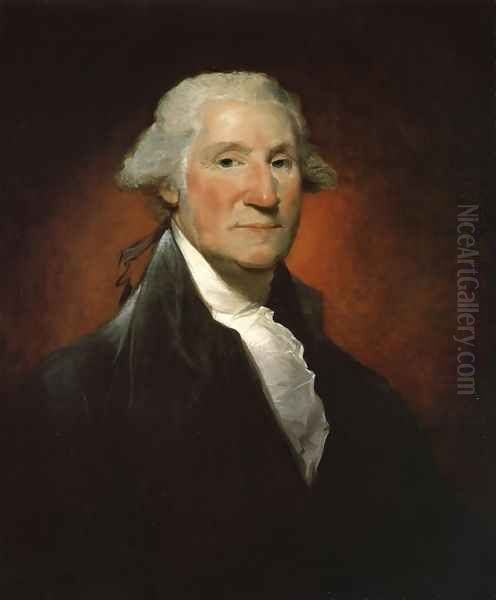

Despite these challenges, Stuart produced three distinct portrait types of Washington from life, all originating from sittings in 1795 and 1796. The first, known as the "Vaughan" type, is a bust-length portrait showing the right side of Washington's face. Several replicas of this type exist. Stuart himself was reportedly unsatisfied with this initial attempt.

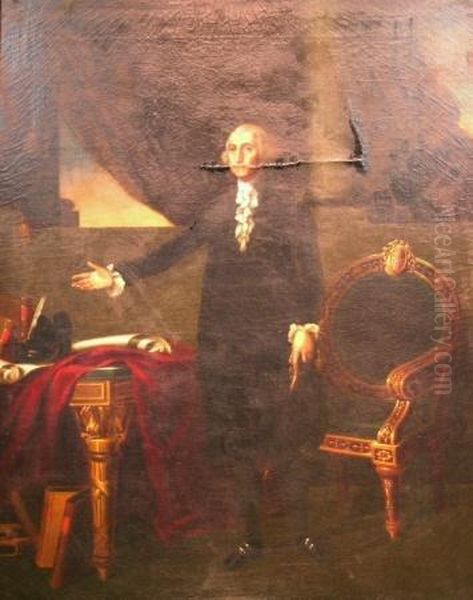

The second major portrait was a full-length depiction known as the "Lansdowne" portrait, commissioned by Senator William Bingham of Pennsylvania as a gift for the Marquis of Lansdowne in England. This portrait presents Washington in a formal, statesmanlike pose, gesturing towards an open space. It incorporates elements of the Grand Manner style, with symbolic objects like books, a sword, and classical columns, signifying Washington's roles as leader, lawgiver, and military hero. Stuart painted several versions of the Lansdowne portrait.

The Iconic Athenaeum Portrait

The third life portrait Stuart painted of Washington, and by far the most famous, is the "Athenaeum" portrait. This unfinished bust-length portrait, showing the left side of Washington's face, was begun in 1796. According to tradition, both George and Martha Washington sat for companion portraits, but Stuart deliberately kept both unfinished. He recognized the immense value of this particular likeness and used it as the model for countless replicas he painted throughout the rest of his career.

Stuart reportedly referred to this unfinished head as his "$100 bill," as he could generate income by painting copies of it on demand (charging about $100 per copy). He is said to have produced over 70 replicas based on the Athenaeum head. This image, with its strong features, firm jaw (possibly accentuated by Washington's dentures), and dignified expression, became the definitive likeness of Washington. It has been reproduced endlessly, most famously serving as the basis for Washington's portrait on the United States one-dollar bill.

The original Athenaeum portraits of George and Martha Washington remained in Stuart's possession until his death. They were later acquired by the Boston Athenaeum (hence the name) and are now jointly owned by the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The unfinished state, particularly the loosely sketched background and clothing, focuses the viewer's attention entirely on Washington's powerful face, contributing to its enduring impact.

Portraitist of the Republic

Stuart's successful portraits of Washington cemented his position as the preeminent portrait painter in the United States. He became the artist of choice for the nation's political, mercantile, and intellectual elite. After Philadelphia ceased to be the capital, Stuart briefly worked in Washington, D.C. (around 1803-1805) before settling permanently in Boston in 1805, where he remained for the rest of his life.

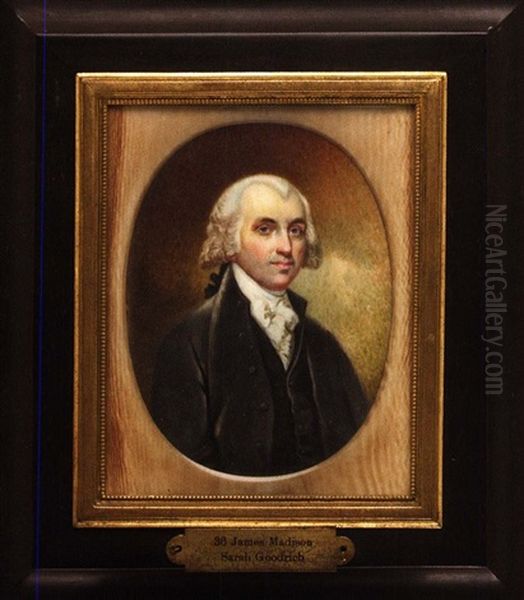

During his American career, Stuart painted an extraordinary gallery of the new nation's leaders. Besides Washington, his sitters included the next four presidents: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. He also painted numerous other significant figures, such as First Ladies Martha Washington and Dolley Madison, Chief Justice John Jay, General Henry Knox, Paul Revere, and prominent merchants, landowners, and their families across New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and Boston.

His portraits captured the spirit of the Federal era, depicting individuals who were shaping a new nation. While sometimes employing elements of the Grand Manner learned in London, his American portraits often favored a more direct, less embellished style, focusing intently on the sitter's face and character. He adapted his approach to suit his American clientele, who perhaps favored republican simplicity over aristocratic grandeur.

Stuart's Distinctive Style and Technique

Gilbert Stuart's artistic style is notable for several key characteristics that distinguished him from his contemporaries and contributed to his lasting influence. He largely abandoned the meticulous, linear approach favored by earlier American portraitists like John Singleton Copley (before Copley moved to London and adopted a looser style). Instead, Stuart worked directly on the canvas with his brushes, building up forms through color and tone rather than relying on preliminary drawing.

His brushwork was fluid, confident, and economical, often described as "feathery." He applied paint in thin layers, known as glazes, particularly in the flesh tones. This technique involved using transparent or semi-transparent layers of color, allowing light to penetrate and reflect off the underlying layers and the white ground of the canvas. This method produced the luminous, vibrant, and remarkably lifelike complexions for which his portraits are celebrated. His skin tones often possess a cool, pearly quality, avoiding the heavy, opaque appearance common in much contemporary portraiture.

Stuart was a master colorist. He claimed to use a limited palette but achieved a rich variety of effects through skillful mixing and layering. He famously advised his students to avoid muddying colors by over-mixing on the palette, instead placing distinct touches of color side-by-side on the canvas and allowing them to blend optically or with minimal blending using a soft brush. This preserved the freshness and vibrancy of the hues.

He concentrated his efforts on the sitter's head, believing the face, and particularly the nose, was the key to capturing a true likeness and the sitter's essential character. Backgrounds and costumes were often treated more broadly and summarily, sometimes appearing unfinished, especially in his later works. This deliberate focus directs the viewer's attention squarely onto the psychological presence of the individual depicted. Stuart possessed an exceptional ability to convey not just the physical features but also the personality, intelligence, and inner life of his subjects.

Mentoring and Influence

Although Stuart did not run a large workshop like Benjamin West, he did occasionally take on students and influenced a generation of American painters. Thomas Sully, who became a leading portraitist in the next generation, spent three weeks with Stuart in Boston around 1807, observing his technique and borrowing paintings to copy. Sully later recalled Stuart's advice and methods, which significantly impacted his own style.

Other artists associated with Stuart include Jacob Eichholtz, a Pennsylvania painter who received encouragement and advice from Stuart, and Stuart's own nephew, Gilbert Stuart Newton, who also became a painter, studying initially with his uncle before moving to England. Through these direct interactions and, more broadly, through the widespread admiration and emulation of his work, Stuart profoundly shaped the course of American portraiture in the early 19th century. He set a standard for technical facility and psychological insight that aspiring artists sought to achieve.

Personality, Anecdotes, and Financial Woes

Gilbert Stuart was known as a man of considerable wit, charm, and eccentricity. He was reportedly a gifted conversationalist and storyteller, using his verbal skills to engage his sitters and capture their fleeting expressions. Numerous anecdotes survive that illustrate his personality. One famous story tells of him on a crowded coach journey in England, amusing fellow passengers with his humor. When asked his profession, he playfully identified himself by various trades before revealing he was a painter, quipping, "I sometimes dress hair," a double entendre referring to both hairdressing and the fine brushwork in painting.

His emphasis on the nose as the most important feature led to another anecdote where he supposedly declared, regarding a sitter's likeness, "The nose is the seat of character!" He was also known for his sharp observations and sometimes caustic remarks. His struggles with painting a reserved Washington, and his eventual success in capturing a definitive likeness, became part of his legend.

Despite his professional success and the high fees he commanded (especially for Washington replicas), Stuart remained perpetually plagued by financial difficulties. His improvidence and perhaps poor business sense meant that he often lived on the edge of insolvency. He was known to delay commissions or leave works unfinished. Even in his later years in Boston, when he was highly revered, he faced financial anxieties. This chronic instability seems to have been an intrinsic part of his complex personality, coexisting with his immense artistic talent.

Final Years, Death, and Legacy

Gilbert Stuart continued to paint actively in Boston until shortly before his death. He remained a dominant figure in the city's art scene, though younger artists with different styles were beginning to emerge. He suffered a stroke in 1824 but partially recovered and resumed painting. He died in Boston on July 9, 1828, at the age of 72.

Due to his outstanding debts, his family was left in difficult circumstances. He was buried in the Old South Burying Ground on Boston Common. Later, when concerns arose about the condition of this burial ground, efforts were made to move his remains, but they could not be definitively located. A monument was later erected in his memory in the Old Burying Ground in Newport, Rhode Island.

Gilbert Stuart's legacy is immense. He created over 1,000 portraits during his lifetime, including definitive images of the most important figures of America's founding era. His technical innovations, particularly his handling of flesh tones and his fluid brushwork, brought a new level of sophistication and vitality to American painting. He successfully blended the traditions of European portraiture, particularly the British school, with a distinctly American sensibility, focusing on character and individuality.

His works are held in major museums across the United States and abroad, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Portrait Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Winterthur Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the National Gallery, London. His Athenaeum portrait of Washington remains one of the most recognizable images in American history. Stuart is rightly considered one of the founding fathers of American art, a master portraitist whose work continues to fascinate and resonate today.

Conclusion: An American Master

Gilbert Stuart's life journey was one of remarkable talent navigating persistent challenges. From humble colonial beginnings, through the crucibles of London and Dublin's competitive art worlds, to his ultimate triumph as the portraitist of the American Republic, Stuart forged a unique artistic identity. His ability to capture not just a likeness but the very essence of his sitters, combined with his technical brilliance—especially his luminous rendering of flesh and his lively brushwork—set his work apart. He provided his nation with enduring images of its founders, forever shaping how Americans visualize their early history. Despite personal flaws and financial instability, Gilbert Stuart's artistic achievement remains undeniable, securing his place as a cornerstone of American art history.