John William Casilear stands as a significant figure in the pantheon of 19th-century American artists. Born in the burgeoning metropolis of New York City in 1811, his life spanned a period of profound transformation in American culture and art. Initially trained in the meticulous craft of engraving, Casilear evolved into one of the most respected landscape painters of his generation, closely associated with the second wave of the Hudson River School and the development of Luminism. His canvases, often intimate in scale but vast in their emotional resonance, capture the serene beauty and tranquil light of the American countryside, leaving behind a legacy of quiet contemplation and technical finesse.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

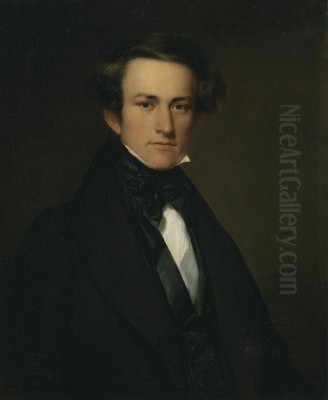

John William Casilear's journey into the world of art began not with a brush, but with a burin. Born on June 25, 1811, in New York City, he showed artistic inclinations early on. At the age of fifteen, around 1826, he embarked upon a formal apprenticeship that would shape his precision and eye for detail. His first master was the prominent New York engraver Peter Maverick.

Under Maverick's guidance, Casilear learned the demanding techniques of line engraving, a craft requiring immense patience and control. Engraving was a vital visual medium in the early 19th century, crucial for reproducing images, illustrating books, and, significantly, creating the intricate designs found on banknotes and official documents. This rigorous training instilled in Casilear a deep appreciation for fine detail and careful composition, qualities that would later distinguish his paintings.

Following his time with Maverick, Casilear sought further instruction from another leading figure in the New York art scene: Asher B. Durand. Durand himself was a master engraver who was increasingly turning his attention towards landscape painting, eventually becoming a foundational figure of the Hudson River School. Studying with Durand proved pivotal for Casilear, exposing him not only to advanced engraving techniques but also planting the seeds for his eventual transition to painting.

During these formative years, Casilear honed his skills as a professional engraver. He gained recognition for his work, particularly in the specialized field of banknote engraving. He produced plates for various banks and eventually became involved with the American Bank Note Company, showcasing his mastery of intricate design and precise execution. For a time, he even established his own engraving firm, demonstrating his proficiency and entrepreneurial spirit within this demanding field.

A Pivotal Journey: Europe and the Embrace of Painting

While Casilear achieved success as an engraver, the allure of painting, particularly landscape painting, grew stronger, significantly influenced by his association with Asher B. Durand. A transformative experience came between 1840 and 1843 when Casilear embarked on an extended tour of Europe. This was not a solitary venture; he traveled with a group of fellow artists who would become lifelong friends and colleagues.

His companions on this formative journey included his mentor Asher B. Durand, the painter John Frederick Kensett, and the artist Thomas Prichard Rossiter. Together, they explored the cultural capitals and scenic landscapes of Europe, visiting renowned museums, studying the works of Old Masters, and sketching directly from nature. This immersion in European art and landscape profoundly impacted Casilear's artistic development.

The experience abroad, particularly the direct engagement with landscape through sketching trips in countries like Switzerland and Italy, solidified Casilear's desire to dedicate himself more fully to painting. He saw firsthand the rich tradition of European landscape art, yet the journey also seemed to reinforce his appreciation for the unique qualities of the American wilderness and countryside that the Hudson River School sought to celebrate.

During this period, the influence of Thomas Cole, the acknowledged founder of the Hudson River School, was also palpable, likely through discussions with Durand and Kensett, who were both deeply inspired by Cole's vision. Upon returning to the United States, Casilear began to exhibit landscape paintings more frequently, signaling a gradual but decisive shift in his artistic focus. Durand reportedly encouraged him in this transition, recognizing his potential as a painter.

Although he continued engraving for some years to support himself, the European tour marked a crucial turning point. The direct observation of nature, the camaraderie with fellow landscape painters, and the exposure to a wider world of art history collectively steered Casilear towards his ultimate calling as a painter of the American scene. By the mid-1850s, he would largely abandon engraving to pursue painting full-time.

The Hudson River School: A National Art Movement

To understand John William Casilear's contribution, one must place him within the context of the Hudson River School, America's first major school of landscape painting. Emerging in the 1820s and flourishing through the 1870s, this movement was more a shared philosophy and subject matter than a formal institution. Its artists sought to capture the grandeur, beauty, and potential of the American landscape, often imbuing their scenes with a sense of awe and national pride.

The movement's spiritual father was Thomas Cole, whose dramatic and often allegorical landscapes of the Catskill Mountains and surrounding regions captured the public imagination. Cole believed that the American wilderness was a unique national treasure, a source of moral and spiritual renewal, contrasting it with the cultivated landscapes of Europe. His work inspired a generation of artists to explore and depict the natural scenery of the nation.

Asher B. Durand, Casilear's mentor, became a leading figure after Cole's death in 1848. Durand advocated for a more direct and detailed study of nature, encouraging artists to paint outdoors (en plein air) as much as possible to capture the specific truths of the American environment. His own works often emphasized the intricate beauty of the forest interior and the peaceful harmony of nature.

Casilear is typically associated with the "second generation" of the Hudson River School, active roughly from the mid-1840s onwards. This generation included artists like his travel companion John F. Kensett, as well as Sanford Robinson Gifford, Frederic Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt. While Church and Bierstadt became known for their monumental canvases depicting dramatic, often exotic landscapes, others like Casilear, Kensett, and Gifford pursued a quieter, more intimate vision.

This second generation often moved beyond the overt Romanticism or moral allegory of Cole, focusing instead on the effects of light and atmosphere, capturing specific moods and times of day. Their work reflected a deep reverence for nature, but often expressed through subtlety and nuance rather than overt drama. It is within this evolution of the Hudson River School that Casilear found his distinctive voice.

Defining Casilear's Vision: The Essence of Luminism

John William Casilear's mature artistic style is closely aligned with Luminism, a distinct mode of American landscape painting that emerged within the broader Hudson River School tradition around the mid-19th century. Luminism is characterized by its profound interest in the effects of light and atmosphere, rendered with a meticulous technique that often conceals visible brushstrokes, creating smooth, polished surfaces.

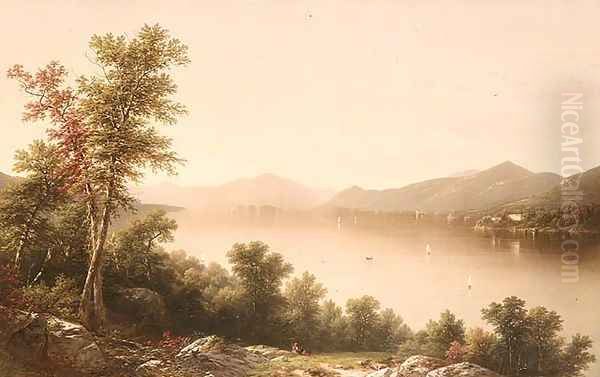

Casilear's paintings epitomize many core tenets of Luminism. His works are renowned for their tranquility, depicting serene landscapes bathed in a soft, diffused light. He excelled at capturing the hazy atmosphere of a summer afternoon, the gentle glow of dawn or dusk, and the reflective qualities of calm water. His compositions are typically balanced and harmonious, often featuring strong horizontal elements that enhance the sense of peace and stability.

His background as an engraver undoubtedly contributed to the precision and clarity found in his paintings. Foliage, rocks, and distant hills are rendered with careful detail, yet this detail is subordinate to the overall atmospheric effect. Unlike the dramatic, sometimes turbulent scenes of Thomas Cole or the vast panoramas of Church and Bierstadt, Casilear's landscapes invite quiet contemplation. They often depict pastoral scenes, gentle lakeshores, or rolling hills, emphasizing nature's restorative and peaceful aspects.

Luminist painters, including Casilear, Kensett, Gifford, Fitz Henry Lane, and Martin Johnson Heade, shared a fascination with how light defines form and creates mood. Casilear's particular contribution lies in his delicate tonal modulations and his ability to suffuse his scenes with a palpable sense of stillness and silence. His color palette tends towards subtle greens, soft blues, warm ochres, and gentle pinks, avoiding harsh contrasts in favor of harmonious transitions.

While Kensett often focused on coastal scenes and Gifford explored dramatic atmospheric effects like sunsets over water or mountains, Casilear frequently depicted inland lakes and pastoral valleys, particularly favoring locations like Lake George in New York, the Catskill Mountains, and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. His vision of nature was one of accessible beauty and gentle repose, rendered with a unique combination of detailed observation and poetic sensitivity to light.

Masterworks: Capturing Tranquility on Canvas

Several key works exemplify John William Casilear's artistic style and his contribution to American landscape painting. Among his most celebrated subjects was Lake George, a location favored by many Hudson River School artists for its picturesque beauty. Casilear returned to this subject multiple times, capturing its serene waters and wooded shores under varying conditions of light and atmosphere.

His paintings titled Lake George (various versions exist, e.g., one from 1857 held by the Wadsworth Atheneum) typically showcase his Luminist approach. Expect to see calm, reflective water dominating the foreground, often mirroring the sky and surrounding hills. The light is soft and pervasive, perhaps illuminating distant mountains with a gentle haze. Foliage is rendered with care, but integrated into a harmonious whole. The overall mood is one of profound peace and stillness, inviting the viewer into a tranquil natural world.

Another signature subject was the Catskill Mountains, the heartland of the Hudson River School. Casilear's View of the Catskill Mountains (or similar titles) often presents a pastoral scene in the foreground leading towards the gentle slopes of the distant range. Unlike Cole's dramatic depictions, Casilear's Catskills are typically bathed in soft, hazy light, emphasizing their peaceful grandeur rather than untamed wildness. The composition is balanced, the details precise yet softened by the atmospheric perspective, embodying his characteristic blend of realism and poetic mood.

An interesting example of his collaborative spirit and connection to his peers is the painting Haines Falls, Kauterskill Clove (circa 1849), which he reportedly worked on with fellow artist David Johnson. This work, depicting a well-known scenic spot, likely combined the strengths of both artists, reflecting the shared interest in detailed rendering of nature prevalent among the second-generation Hudson River School painters.

These representative works highlight Casilear's consistent artistic concerns: the meticulous rendering learned from engraving, the profound sensitivity to light and atmosphere characteristic of Luminism, and a preference for depicting the gentle, restorative beauty of the American landscape. His canvases, though often modest in size compared to the epics of Church or Bierstadt, possess a quiet intensity and enduring appeal.

A Circle of Artists: Friends and Contemporaries

John William Casilear did not create in isolation. He was part of a vibrant community of artists centered primarily in New York City, interacting closely with many of the leading figures of the Hudson River School and related movements. His relationships were built through shared apprenticeships, travel, exhibitions, and mutual respect.

His most significant early relationship was with Asher B. Durand. More than just a teacher, Durand became a lifelong friend and mentor who profoundly influenced Casilear's decision to pursue painting. Their European journey together cemented this bond. Similarly, John F. Kensett, another travel companion, remained a close associate. Both Kensett and Casilear shared a similar artistic sensibility, becoming key figures in the development of Luminism, often painting similar subjects with a shared emphasis on light and tranquility.

The influence of Thomas Cole, though perhaps less direct than Durand's, was foundational for the entire Hudson River School generation, providing the initial inspiration for celebrating the American landscape. Casilear certainly knew Cole's work and likely absorbed his ethos through his close association with Durand and Kensett.

Casilear also maintained a close friendship with Sanford Robinson Gifford, another prominent Luminist painter known for his mastery of atmospheric effects, particularly hazy sunsets and light-filled landscapes. Their friendship was deep enough that after Gifford's untimely death, Casilear was among those entrusted with handling his estate and possibly assisting with unfinished works, demonstrating the trust and camaraderie within this circle.

He collaborated directly with artists like David Johnson, as seen in the Haines Falls painting, indicating a willingness to share creative endeavors. He was also contemporary with other notable Hudson River School figures. These included Jasper Francis Cropsey, famed for his vibrant autumnal scenes; Worthington Whittredge, known for his immersive woodland interiors; and Jervis McEntee, whose landscapes often possessed a more melancholic, Tonalist-leaning mood.

While his style differed significantly, Casilear worked during the same era as Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, the painters of grand, often exotic panoramas. Their dramatic works represented one major direction of the Hudson River School, while Casilear's quieter, more intimate Luminist approach represented another significant facet of mid-19th century American landscape art. He was also contemporary with key figures primarily associated with Luminism like Fitz Henry Lane and Martin Johnson Heade, known especially for their coastal and marsh scenes, and William Trost Richards, whose meticulous marine paintings shared a similar precision. Even George Inness, who moved from Hudson River School aesthetics towards a more subjective Tonalism, was a contemporary whose career overlapped with Casilear's later years, illustrating the evolving landscape tradition. This network of friendships, collaborations, and shared artistic environment was crucial to Casilear's development and career.

Recognition and a Dedicated Career

John William Casilear's talent and dedication earned him significant recognition within the American art world during his lifetime. His transition from a respected engraver to a celebrated painter was marked by increasing involvement with the premier art institution of the time, the National Academy of Design in New York City.

He began exhibiting his paintings at the National Academy as early as the 1830s. His growing reputation led to his election as an Associate Member of the Academy in 1833. This was a significant step, acknowledging his standing within the artistic community. As his focus shifted decisively towards painting, his stature continued to grow.

A major milestone came in 1851 when John William Casilear was elected a full Academician (NA) by the National Academy of Design. This honor solidified his position as one of the country's leading artists. He remained a consistent exhibitor at the Academy's annual exhibitions for decades, showcasing his evolving mastery of landscape painting to critics and collectors. Records indicate he exhibited well over fifty works there throughout his long career.

Around 1854, Casilear made the definitive break from his earlier profession by largely giving up engraving and opening his own painting studio in New York City. This move signified his full commitment to landscape painting, allowing him to dedicate his time and energy entirely to his art. He became known for his consistent output of high-quality, finely finished landscapes that found favor with patrons who appreciated their serene beauty and meticulous craftsmanship.

His works were acquired by important collectors and eventually found their way into major public collections. While perhaps not achieving the same level of widespread fame or financial success as Church or Bierstadt with their monumental canvases, Casilear commanded steady respect and admiration for the quiet poetry and technical excellence of his art. He remained an active and respected member of the New York art scene until his later years.

Enduring Legacy: Casilear's Place in American Art

John William Casilear passed away on August 17, 1893, in Saratoga Springs, New York, leaving behind a significant body of work that secures his place as a key figure in 19th-century American art. His primary legacy lies in his contribution to the Hudson River School, particularly its Luminist phase. He masterfully blended the precision learned through engraving with a profound sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere.

His paintings offer a distinct vision of the American landscape – one characterized by peace, harmony, and gentle beauty. In contrast to the dramatic or sublime views favored by some contemporaries, Casilear's work invites quiet reflection, capturing the subtle moods of nature with remarkable delicacy. He demonstrated that the American landscape could be portrayed not only as wild and majestic but also as intimate and restorative.

His role within the Luminist movement is crucial. Alongside Kensett and Gifford, he helped define this uniquely American approach to landscape painting, emphasizing stillness, clarity, and the transcendental qualities of light. His meticulous technique, resulting in smooth surfaces and finely rendered details bathed in soft illumination, became a hallmark of his style and influenced others within the movement.

Today, John William Casilear's paintings are held in the permanent collections of major American museums, ensuring their accessibility to future generations. Institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the New-York Historical Society, among others, preserve and exhibit his work.

His enduring appeal rests on the timeless quality of his landscapes. They transport viewers to moments of serene beauty, capturing the quiet poetry of the American countryside with a skill and sensitivity that continue to resonate. He remains celebrated as a master of light, an artist who found profound beauty in the tranquil moments of nature and rendered them with exceptional grace and technical skill.

Conclusion

John William Casilear's artistic journey from meticulous engraver to celebrated landscape painter reflects a deep engagement with the artistic currents of his time and a personal quest for capturing the essence of the American environment. As a vital member of the Hudson River School's second generation and a key proponent of Luminism, he crafted a unique visual language characterized by serene compositions, exquisite detail, and an unparalleled sensitivity to the effects of light and atmosphere. His paintings, imbued with a sense of peace and quiet contemplation, stand as enduring testaments to the tranquil beauty of the 19th-century American landscape and secure his legacy as a master of light and tranquility in American art history.