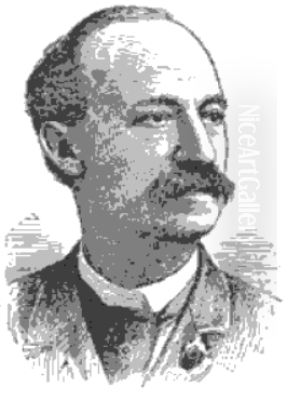

Norton Bush stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in nineteenth-century American landscape painting. Active primarily on the West Coast, he carved a unique niche for himself by specializing in lush, evocative depictions of tropical landscapes gleaned from his extensive travels in Central and South America, alongside renderings of his adopted California home. Born in 1834 and passing away in 1894, Bush's life and career bridged the era of the Hudson River School's dominance with the burgeoning art scene of California, reflecting both the influence of established Eastern traditions and the distinct character of the American West and the exotic allure of the tropics. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and a profound sense of nature's grandeur, offers a fascinating window into the artistic and exploratory spirit of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Norton Bush was born in Rochester, New York, on February 22, 1834. His initial artistic inclinations found guidance under a local Rochester painter named James Harris. Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Bush recognized the need for more advanced training and exposure to the prevailing artistic currents. He subsequently moved to New York City, the epicenter of the American art world at the time.

In New York, Bush immersed himself in the study of landscape painting. Critically, he came under the influence of prominent figures associated with the Hudson River School, America's first major school of landscape painting. He studied the works, and potentially directly with, Jasper Francis Cropsey, known for his vibrant autumnal scenes, and the renowned Frederic Edwin Church. Church, a student of the Hudson River School's founder Thomas Cole, was already gaining fame for his large-scale, dramatic landscapes, particularly those inspired by his own travels to South America. This exposure to Church's style and subject matter would prove deeply influential on Bush's later career trajectory. The Hudson River School's emphasis on detailed observation, romantic sensibility, and the portrayal of nature as a manifestation of the divine or sublime undoubtedly shaped Bush's developing aesthetic.

The Journey West and the Call of the Tropics

The lure of opportunity and new horizons drew Norton Bush westward. In 1853, at the young age of 19, he embarked on a significant journey, leaving New York for California. This was the era of the California Gold Rush, a period of rapid growth and transformation for the state, attracting people from all walks of life, including artists seeking new landscapes and patronage. Bush's journey itself was formative. Rather than taking an overland route, he sailed from New York, undertaking the long and arduous voyage around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America.

This maritime route, while challenging, provided Bush with his first direct exposure to the tropical environments that would become central to his artistic identity. The journey offered glimpses of exotic coastlines, unique flora, and dramatic atmospheric effects distinct from the temperate landscapes of the northeastern United States. This experience likely planted the seeds for his later, more focused expeditions into the heart of Central and South America. Upon arriving in California, he initially settled in San Francisco, the burgeoning metropolis of the West Coast, though he also spent a brief period in Sacramento before establishing San Francisco as his primary base.

Exploring Latin America: The Source of Inspiration

Bush's initial exposure to the tropics during his voyage to California ignited a lasting fascination. Throughout his career, he undertook multiple expeditions to Central and South America, seeking out the dramatic and verdant landscapes that would define his most characteristic work. His travels took him to regions such as Panama, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Peru. These journeys were not mere sightseeing trips; they were intensive periods of observation and sketching, gathering the raw material that he would later transform into finished oil paintings in his San Francisco studio.

His choice of subject matter aligned him with the spirit of exploration prevalent in the mid-nineteenth century, partly inspired by the writings and scientific expeditions of figures like the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. Humboldt's descriptions of the South American landscape had captivated artists and scientists alike, encouraging a view of the natural world that blended empirical observation with a sense of wonder and the sublime. Frederic Edwin Church had famously followed Humboldt's routes, producing iconic works like "The Heart of the Andes." Bush, similarly, sought to capture the unique beauty and exoticism of these regions, focusing on their dense jungles, volcanic peaks, serene lakes, and dramatic coastlines.

These travels provided Bush with a distinct artistic advantage. While many American landscape painters focused on the scenery of the Northeast or the dramatic vistas of the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada (subjects Bush also painted), his specialization in tropical scenes offered patrons and the public something different and alluringly exotic. His paintings of locations like the Chagres River in Panama or Lake Nicaragua became signature pieces, transporting viewers to faraway lands filled with lush vegetation and atmospheric light.

Artistic Style: Detail, Light, and the Sublime

Norton Bush's artistic style reflects his Hudson River School training, particularly the influence of Frederic Edwin Church, yet possesses its own distinct qualities. His work is generally characterized by meticulous attention to detail, a high degree of finish, and a strong emphasis on the effects of light and atmosphere. He rendered foliage, water, and geological formations with considerable precision, grounding his often dramatic scenes in careful observation.

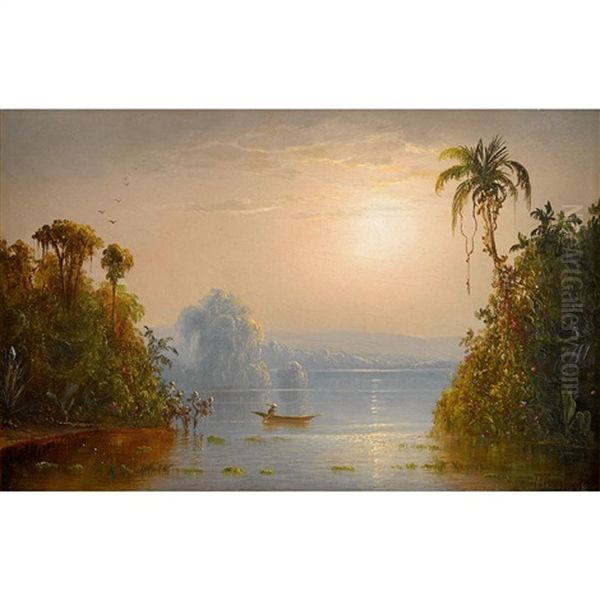

Like Church and other painters sometimes associated with Luminism (a related mid-19th-century American style focusing on light and atmosphere, often associated with artists like John Frederick Kensett and Sanford Robinson Gifford), Bush was adept at capturing the nuances of light. His tropical scenes often feature dramatic sunsets or sunrises, with glowing skies reflected in tranquil waters. He skillfully depicted the humid, hazy atmosphere characteristic of these regions, imbuing his landscapes with a palpable sense of place. His handling of light was crucial in creating mood, ranging from serene tranquility to awe-inspiring grandeur.

A key element in Bush's work is the evocation of the sublime – the feeling of awe, wonder, and sometimes even delightful terror experienced in the face of vast and powerful nature. His compositions often emphasize the immense scale of the natural world, contrasting towering mountains, expansive skies, or dense, overwhelming jungles with small, sometimes barely visible, human figures or elements of human presence (like a small boat or hut). This technique served to highlight the majesty and power of nature and the relative insignificance of humankind within it, a common theme in nineteenth-century Romantic landscape painting inherited from artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand.

While influenced by Church, Bush's work sometimes differs in scale and perhaps intensity. He often worked on a more modest scale than Church's monumental canvases. His tropical scenes, while detailed and evocative, occasionally possess a quieter, more idyllic quality compared to the high drama found in some of Church's major South American works. Nonetheless, the shared interest in exotic locales, detailed rendering, and atmospheric effects clearly links the two artists.

Major Themes: Tropical Paradises and California Vistas

Norton Bush's oeuvre can be broadly divided into two main geographical themes: the tropical landscapes of Latin America and the scenery of his adopted state, California. His tropical paintings form the most distinctive part of his legacy. These works typically depict lush, verdant jungles, often bordering rivers or lakes. Palms, ferns, flowering vines, and other exotic flora are rendered with botanical care. Water is a frequent element, shown as calm, reflective surfaces mirroring the sky and surrounding vegetation, contributing to the sense of serenity and untouched paradise.

Works depicting locations like the Chagres River in Panama or scenes in Nicaragua and Ecuador often feature dramatic skies – vibrant sunsets casting a warm glow over the landscape or gathering storm clouds hinting at nature's power. The interplay of light and shadow across the dense foliage and water surfaces is a hallmark of these paintings. They convey a sense of warmth, humidity, and the vibrant life of the tropics, offering viewers an escape to seemingly unspoiled natural realms.

Alongside his tropical scenes, Bush also painted the landscapes of California. He depicted the rolling hills, oak-studded valleys, and coastal areas familiar to residents of the state. Notably, he also tackled the grandeur of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, a subject that captivated many California artists, including renowned figures like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Hill. Bush's California landscapes, while perhaps less exotic than his tropical views, demonstrate his versatility and his engagement with the scenery of his home region. Paintings like Mount Diablo showcase his ability to capture the specific light and atmospheric conditions of the California environment.

Representative Works

Among Norton Bush's many paintings, certain works stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns. Tropical Sunset (1890) is a fine example of his later work, showcasing his mastery of light and atmosphere in a tropical setting. Typically, such a painting would feature a luminous sky filled with the warm colors of dusk, reflected in a calm body of water. Dense, dark foliage would frame the scene, rendered with characteristic detail, creating a contrast between the receding, light-filled distance and the richer, darker foreground. The overall mood would likely be one of tranquility and awe at the beauty of the natural world.

Other notable titles that recur in discussions of his work include Lake Nicaragua, Scene on the Chagres River, Cordillera Mountains, Ecuador, and various views of the Andes. These titles indicate his focus on specific, identifiable locations visited during his travels. His California subjects are represented by works such as Mount Tamalpais, Mount Diablo, and scenes of the San Joaquin Valley or the Sierra Nevada. Each of these works, whether tropical or Californian, would typically exhibit his careful draftsmanship, detailed rendering, and sensitivity to atmospheric effects.

A Career in the California Art Scene

Upon settling in California, Norton Bush became an active participant in the developing art community of San Francisco. He established a studio and began exhibiting his work, quickly gaining recognition for his skillfully rendered and appealing landscapes, particularly the novel tropical scenes. He became a member of the San Francisco Art Association (SFAA), the leading art organization in the city, which played a crucial role in promoting art and artists through exhibitions and the establishment of an art school (the California School of Design, later the San Francisco Art Institute).

Bush's involvement with the SFAA was significant; he served as a director of the association from 1878 to 1880, indicating his respected position within the local art world. He also exhibited his work regularly at venues like the Mechanics' Institute Fairs in San Francisco, which were important showcases for art and industry on the West Coast. Furthermore, he maintained connections with the East Coast art establishment, occasionally exhibiting at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York. He was also associated with the Bohemian Club of San Francisco, a social and cultural organization that included many artists and writers among its members.

His success was bolstered by significant patronage. Wealthy California entrepreneurs, enriched by the Gold Rush and subsequent economic development, became important collectors. Figures like William C. Ralston, a prominent San Francisco financier and founder of the Bank of California, and Henry Meiggs, a railroad and lumber magnate (who later had significant operations in South America), commissioned works from Bush and reportedly helped finance some of his travels to Latin America. This patronage not only provided financial support but also suggests that Bush's particular brand of landscape – both the familiar California scenes and the exotic tropical views – resonated with the tastes of influential Californians. His contemporaries in the California art scene included painters like Thomas Hill, William Keith, Albert Bierstadt (who made extended visits), Charles Christian Nahl, and Virgil Williams, the first director of the SFAA's art school. Bush navigated this active environment, establishing himself as a leading landscape painter.

The World's Columbian Exposition and Final Years

Towards the end of his career, Norton Bush took on a demanding role related to a major international event. He served as an art director or commissioner for the California exhibit at the World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893. This massive world's fair was a significant cultural event, showcasing achievements in art, science, and industry from around the globe. His involvement reflects his standing in the California art community, entrusted with helping to represent the state's artistic accomplishments on a national and international stage. He reportedly received honors for his work in this capacity.

However, this prestigious undertaking appears to have taken a severe toll on his health. Sources indicate that the stress and overwork associated with organizing the exposition contributed to heart problems. This period seems to mark a decline in his well-being.

The circumstances surrounding Norton Bush's death in 1894 are somewhat varied in accounts, though the most frequently cited narrative in reliable art historical sources points towards a tragic end. While some earlier accounts attribute his death solely to heart disease exacerbated by his work for the Exposition, more detailed biographical records, such as those compiled by art historian Edan Milton Hughes, state that Bush suffered from depression, possibly linked to financial difficulties (perhaps related to the economic downturns of the era or the earlier collapse of his patron Ralston's financial empire) and the loss of friends. According to these sources, he died by suicide in his studio at the old Donohoe Building in San Francisco on May 15, 1894. He was found near Middle Creek, San Mateo County, having ended his life. He was 60 years old. This sad conclusion cut short the career of a talented and recognized artist.

Legacy and Place in Art History

Norton Bush left behind a significant body of work, although his legacy was impacted by a catastrophic event. A considerable number of his paintings were likely destroyed in the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire, which ravaged much of the city, including artists' studios and collectors' homes. Despite this loss, enough of his work survives to secure his reputation.

His paintings are held in the collections of several important institutions, particularly in California. These include the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (de Young Museum), the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, the Oakland Museum of California, the California Historical Society, and the Palmer Museum of Art at Penn State University, among others. His work also continues to appear on the art market, with auction results demonstrating sustained interest among collectors of historical American and Californian art. A sale price of $58,500 for one of his works in 2024, as mentioned in the initial prompt's sources, attests to his continued market relevance.

In the broader narrative of American art history, Norton Bush is primarily recognized as a key figure in the development of landscape painting in California during the latter half of the nineteenth century. He successfully adapted the aesthetics of the Hudson River School to Western and tropical subjects. While perhaps not achieving the national fame of figures like Church or Bierstadt, his specialization in Central and South American landscapes gives him a unique position. He, along with Church and other artists like Martin Johnson Heade and Louis Rémy Mignot who also ventured south, contributed to a specific subgenre of American landscape painting focused on the tropics, satisfying a public fascination with exotic lands and scientific exploration.

His influence can be seen in his contribution to the institutional art life of San Francisco through his involvement with the SFAA. He helped establish a tradition of landscape painting on the West Coast that would continue to evolve with subsequent generations of artists like William Keith, and later figures associated with California Impressionism such as William Wendt or Guy Rose, although their styles differed significantly. Bush remains an important artist for understanding the artistic culture of nineteenth-century California and the American fascination with landscape, both domestic and exotic.

Conclusion

Norton Bush's career represents a compelling intersection of artistic tradition, personal exploration, and regional identity. Trained in the ethos of the Hudson River School, he carried its detailed realism and romantic sensibility westward to California and southward to the tropics. His voyages yielded a distinctive body of work celebrating the lush beauty and sublime power of Central and South American landscapes, offering a unique counterpoint to the more commonly depicted scenes of North America. As an active member of the San Francisco art community and a painter patronized by key figures of the era, he played a vital role in the cultural life of nineteenth-century California. Though his life ended tragically and many of his works were lost, Norton Bush's surviving paintings endure as testaments to his skill, his adventurous spirit, and his dedication to capturing the diverse and awe-inspiring landscapes of the Americas. He remains a significant figure for anyone studying the art of California and the broader currents of American landscape painting.