Joseph Wright, famously known as Joseph Wright of Derby, stands as a pivotal figure in British art history. Born in the heart of England during a period of profound intellectual and industrial transformation, his work uniquely captures the spirit of the Enlightenment and the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Unlike many of his contemporaries who focused on aristocratic portraiture or classical landscapes, Wright turned his gaze towards science, industry, and the dramatic interplay of light and shadow, creating a body of work that remains both visually stunning and historically significant. His paintings serve as crucial documents of an era defined by curiosity, innovation, and societal change.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Joseph Wright was born in Derby, Derbyshire, on September 3, 1734. His background was solidly middle-class; his father, John Wright, was a respected attorney and later served as the town clerk. This professional environment likely instilled in the young Wright a sense of discipline and perhaps an appreciation for the burgeoning intellectual life of the English provinces. Derby itself, while not London, was becoming a hub of activity, influenced by the early stirrings of industrialisation in the Midlands.

Recognising his artistic inclinations, Wright's family supported his ambition to become a painter. In 1751, at the age of seventeen, he travelled to London to undertake formal training. He entered the studio of Thomas Hudson, a leading portrait painter of the day. Hudson's studio was a significant training ground, most famously having also tutored the great Sir Joshua Reynolds, who would become the first president of the Royal Academy. Wright spent two years under Hudson's tutelage (1751-1753).

This initial period in London exposed Wright to the established conventions of portraiture and the broader London art scene. Hudson's style was competent, if somewhat formulaic, typical of mid-century British portraiture derived from the traditions of Godfrey Kneller and his followers. Wright would have learned the fundamentals of drawing, paint handling, and capturing a likeness, skills essential for any aspiring professional artist of the time.

Return to Derby and Developing a Unique Vision

After his initial training with Hudson, Wright returned to Derby to establish his own practice, primarily as a portrait painter. Portraiture was the most reliable source of income for artists outside the metropolis, and Wright quickly found clients among the local gentry and the increasingly prosperous merchant and professional classes of the Midlands. However, he returned to London for a further fifteen months (1756-1757) to work as an assistant to Hudson, likely refining his skills and perhaps seeking further connections.

It was upon his more permanent return to Derby that Wright began to truly forge his distinctive artistic identity. While continuing to paint portraits, he started experimenting with subjects and techniques that set him apart. He became fascinated with the effects of artificial light, particularly candlelight and lamplight, and the dramatic contrasts between light and deep shadow – a technique known as chiaroscuro.

This interest in strong tonal contrasts had precedents in art history, notably in the work of Italian Baroque master Caravaggio and the Dutch Golden Age giant Rembrandt van Rijn. Wright likely knew their work through prints, if not original paintings. Another potential influence, particularly for nocturnal scenes illuminated by a single artificial source, might be the French painter Georges de La Tour. However, Wright adapted these influences to his own time and place, applying dramatic lighting not just to religious or genre scenes, but to contemporary subjects reflecting the intellectual and industrial ferment around him.

The Scientific Enlightenment on Canvas

Joseph Wright lived and worked during the height of the Enlightenment, an era characterised by a profound faith in reason, empirical observation, and scientific inquiry. Wright was not merely an observer of this movement; he was deeply engaged with its spirit and personally connected to some of its key figures in the Midlands. His most celebrated works are those that depict scientific experiments and philosophical discussions, illuminated with his signature dramatic lighting.

Perhaps his most famous painting is A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery (c. 1766). This masterpiece depicts a group of figures gathered around an orrery, a mechanical model of the solar system, which is illuminated from within, casting a powerful glow on the faces of the onlookers. The central figure, the philosopher (possibly modelled on a friend, John Whitehurst), explains the workings of the universe. The diverse group surrounding him, including men, women, and children, displays reactions ranging from rapt attention to intellectual contemplation and childlike wonder. The light emanating from the model sun symbolises the illuminating power of knowledge and reason, replacing the divine light often found in earlier religious art.

Another iconic work is An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768). This painting captures a moment of high drama as a natural philosopher demonstrates the properties of a vacuum using an air pump. A white cockatoo is placed within a glass receiver from which the air is being evacuated, causing the bird distress. The reactions of the observers are varied and complex: a young girl turns away, unable to watch, while others gaze intently, fascinated by the scientific process. The scene is lit by a single candle, hidden behind a large flask, creating stark shadows and highlighting the emotional intensity of the moment. The painting explores themes of life and death, the ethics of scientific experimentation, and the awe inspired by understanding the natural world.

These paintings were radical for their time. They elevated scientific subjects to the level of history painting, traditionally considered the highest genre. Wright treated these scenes with a seriousness and dramatic intensity previously reserved for biblical or mythological narratives. His use of chiaroscuro was not merely stylistic; it underscored the metaphorical enlightenment offered by science, emerging from the darkness of ignorance.

Connections to the Lunar Society

Wright's interest in scientific themes was nurtured by his close association with members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, an informal group of prominent industrialists, natural philosophers, and intellectuals who met regularly between roughly 1765 and 1813. Though based in Birmingham, the society's influence extended throughout the Midlands, and Wright, based in nearby Derby, moved within this circle.

Members included pioneers like the potter Josiah Wedgwood, the engine inventors James Watt and Matthew Boulton, the chemist and theologian Joseph Priestley, and the physician, botanist, and poet Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles Darwin). These men were at the forefront of scientific discovery and industrial innovation. Wright painted portraits of several members, including Wedgwood and Darwin, and shared their enthusiasm for progress and knowledge.

His scientific paintings can be seen as visual manifestations of the Lunar Society's interests – popularising science, exploring natural phenomena, and celebrating human ingenuity. The Orrery and Air Pump paintings, while not depicting actual Lunar Society meetings, capture the atmosphere of intellectual excitement and collaborative discovery that characterised the group. Wright provided a visual language for the Enlightenment ideals championed by his friends and patrons.

Capturing the Industrial Revolution

Joseph Wright is often hailed as "the first professional painter to express the spirit of the Industrial Revolution." While other artists occasionally depicted industrial scenes, Wright engaged with these subjects more consistently and with greater artistic ambition. Living and working in Derbyshire, one of the cradles of industrialisation, he witnessed firsthand the transformative power of new technologies and manufacturing processes.

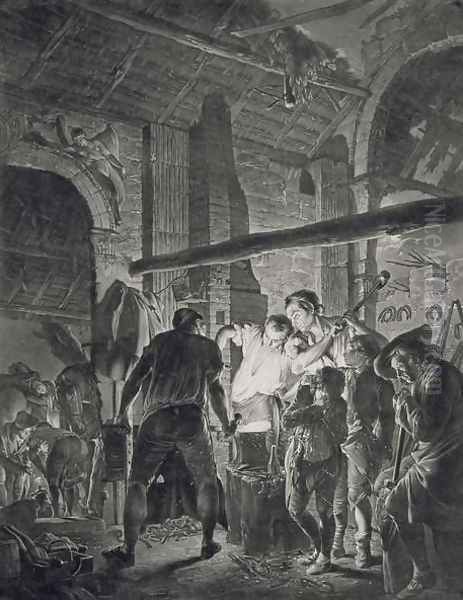

He painted scenes of blacksmiths' shops, iron forges, and early factories, often employing his characteristic nocturnal settings and dramatic lighting. Works like An Iron Forge (1772) and The Blacksmith's Shop (1771) depict labourers engaged in their work, illuminated by the intense heat and light of the forge fire. These are not simply documentary records; they possess a heroic quality, celebrating the power and skill involved in metalworking. The intense light emanating from the forge often takes on an almost spiritual intensity, suggesting the transformative power of industry.

Later, he painted views of Richard Arkwright's cotton mills at Cromford by night, lit by the glow from their numerous windows (Arkwright's Cotton Mills by Night, c. 1782-83). These images capture the relentless activity of the early factory system, which operated around the clock. While some might see a critique of industrial labour in these scenes, Wright's approach often seems more focused on the visual drama and the sublime power inherent in these new industrial landscapes. He found beauty and awe in subjects that many contemporaries might have dismissed as mundane or ugly.

His engagement with industrial themes distinguishes him sharply from London-based contemporaries like Thomas Gainsborough or George Romney, who largely catered to aristocratic tastes for elegant portraits and idealised landscapes. Wright's willingness to tackle modern, industrial subjects marks him as a forward-looking artist, documenting and interpreting the profound changes reshaping British society. Philip James de Loutherbourg was another artist who depicted industrial scenes like Coalbrookdale by night, but Wright's focus was perhaps more sustained and integrated into his core artistic identity.

The Grand Tour and Italian Influence

Like many ambitious British artists of his era, Joseph Wright undertook a Grand Tour to Italy, hoping to enhance his skills and reputation by studying classical antiquity and the Italian masters firsthand. He travelled with his wife, Ann Swift (whom he married in 1773), and fellow artist John Downman, setting off later in 1773 and remaining abroad until 1775.

His time in Italy proved highly influential, though perhaps not in the conventional ways. While he studied classical sculpture and Renaissance painting in Rome and Florence, he seems to have been most profoundly affected by the Italian landscape and natural phenomena. He was particularly captivated by Naples and the surrounding area, witnessing several eruptions of Mount Vesuvius.

This experience inspired a series of dramatic paintings of Vesuvius erupting by night, which became some of his most popular works upon his return to England. These paintings, such as Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples (c. 1776-80), combine topographical accuracy with a heightened sense of drama and the sublime – the feeling of awe mixed with terror inspired by the overwhelming power of nature. The fiery glow of the volcano provided a natural subject perfectly suited to Wright's mastery of light and shadow.

His Italian landscapes also show the influence of 17th-century masters like Claude Lorrain, known for his idealised, light-filled scenes, and Salvator Rosa, famed for his wild, rugged landscapes. Wright absorbed these influences but adapted them to his own sensibility, often focusing on subterranean grottos, moonlit ruins, or coastal scenes under dramatic lighting conditions. The Italian journey broadened his subject matter and reinforced his fascination with the power and mystery of light, whether natural or artificial.

Portraiture: Capturing the Midlands Elite

Throughout his career, portraiture remained a crucial part of Joseph Wright's output. While his subject paintings brought him wider fame, his portraits provided a steady income and connected him with the leading figures of his region. His sitters were typically members of the Midlands gentry, prosperous industrialists, scientists, and intellectuals – the very people shaping the region's future.

Wright's portrait style is generally characterised by its directness and psychological insight. He often eschewed the fashionable elegance and flattering idealisation favoured by London rivals like Reynolds, Gainsborough, or Romney. Instead, Wright aimed for a strong likeness and a sense of the sitter's character and social standing. His portraits feel solid and grounded, reflecting the pragmatic and industrious nature of many of his clients.

He often incorporated elements related to the sitter's profession or interests, particularly in portraits of his scientific and industrialist friends. For example, his portrait of the clockmaker and geologist John Whitehurst might include geological specimens, while his portrait of industrialist Richard Arkwright conveys a sense of authority and shrewdness.

While perhaps less glamorous than the society portraits being produced in London, Wright's portraits offer a valuable record of the provincial elite during a period of significant social mobility and change. They reveal a world where scientific inquiry and industrial enterprise were gaining prominence and respectability. His straightforward approach often resulted in portraits of considerable power and presence.

Landscape Painting and the Romantic Sensibility

Beyond his famous scientific and industrial scenes, Joseph Wright was also a significant landscape painter. His landscapes often share the dramatic qualities found in his other work, focusing on specific times of day or unusual natural phenomena to explore the effects of light. Moonlit scenes were a particular favourite, allowing him to exploit subtle tonal variations and create moods of quiet contemplation or eerie mystery.

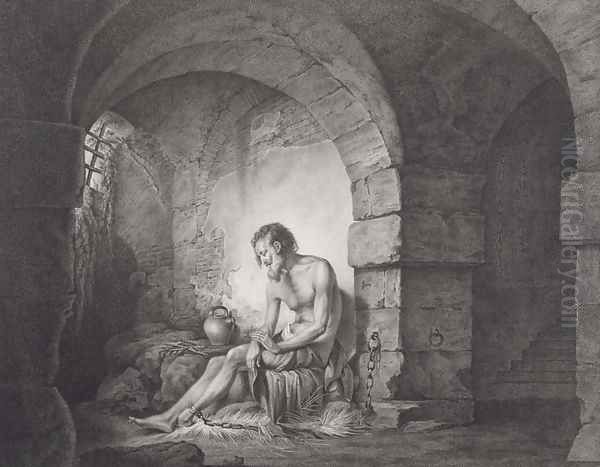

He painted views of the local Derbyshire landscape, including the dramatic scenery of the Peak District with its caves and rocky outcrops. Works like Dovedale by Moonlight (c. 1784-85) or A Cavern, Evening (1774) showcase his ability to capture the textures of rock and foliage under specific lighting conditions. These paintings often evoke a sense of the sublime, emphasizing the grandeur and sometimes unsettling power of nature.

His Italian landscapes, particularly those depicting grottos near Naples or moonlit views of classical ruins, also contribute to his reputation as a landscape artist. In these works, he often combined topographical observation with a heightened emotional atmosphere.

Wright's approach to landscape, with its emphasis on specific light effects, dramatic natural phenomena, and the evocation of mood, aligns him with the emerging sensibilities of Romanticism. He can be seen as a precursor to later British landscape painters like J.M.W. Turner, who would push the exploration of light and atmosphere even further. While perhaps less influential than contemporaries like Richard Wilson, who is often called the father of British landscape painting, Wright's landscapes form an important and distinctive part of his oeuvre, demonstrating his consistent fascination with light and its power to transform the visible world.

Literary and Historical Subjects

While best known for his scientific and industrial themes, Joseph Wright also engaged with literary and historical subjects throughout his career. These works allowed him to explore narrative, allegory, and human emotion in different contexts, often still employing his signature dramatic lighting to enhance the story's impact.

One notable example is The Old Man and Death (1773), based on one of Aesop's fables. The painting depicts an elderly woodcutter who, exhausted by his labour, calls upon Death to relieve him. When Death appears (as a skeleton), the old man, suddenly fearful, changes his mind and merely asks Death to help him lift his bundle of sticks. Wright captures the moment of confrontation with stark realism and dramatic lighting, emphasizing the old man's gnarled physique and the chilling presence of Death.

Another significant literary painting is The Corinthian Maid (or The Origin of Painting, 1782-84). Based on a story recounted by Pliny the Elder, it depicts Dibutades, a potter's daughter in ancient Corinth, tracing the shadow of her departing lover on a wall, thus inventing the art of drawing. The scene is illuminated by lamplight, casting the crucial shadow and creating an intimate, poignant atmosphere. This work reflects on the nature of art, memory, and love.

Wright also painted scenes from contemporary literature, such as Maria and her Dog Silvio from Laurence Sterne's popular novel A Sentimental Journey. These literary and historical paintings demonstrate Wright's versatility and his engagement with the broader cultural currents of his time. They show him applying his unique visual style to traditional genres, often imbuing them with a fresh psychological intensity.

Later Life, Career, and the Royal Academy

After returning from Italy in 1775, Wright initially hoped to establish himself in a larger artistic centre. He spent two years in Bath (1775-1777), a fashionable spa town, attempting to attract portrait commissions from wealthy visitors. However, he faced stiff competition and found less demand for his more experimental subject pictures. Disappointed, he returned permanently to Derby in 1777, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Despite being based provincially, Wright maintained connections with the London art world, primarily through exhibiting at the Society of Artists and, later, the Royal Academy of Arts. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1781 and a full Academician (RA) in 1784. However, he famously declined the latter honour, apparently feeling slighted by the circumstances of his election or perhaps due to a dispute over the hanging of his pictures. This refusal cemented his reputation as something of an outsider, independent of the London establishment.

His relationship with the Royal Academy remained complex. He continued to exhibit there occasionally but often preferred provincial venues or organising his own exhibitions. This independence, while perhaps limiting his national profile during his lifetime, reinforced his identity as 'Wright of Derby', an artist deeply rooted in his region.

In his later years, Wright suffered increasingly from asthma, which affected his ability to work. He continued to paint, though perhaps with less intensity than before. He passed away in Derby on August 29, 1797, at the age of 62. His wife, Ann, outlived him, dying in 1809. He was buried in St Alkmund's Church in Derby.

Artistic Techniques and Materials

Joseph Wright's distinctive style relied heavily on his masterful manipulation of light and shadow. His chiaroscuro was often more dramatic and his shadows deeper than those typically seen in British painting of the period. He achieved these effects through careful tonal control, building up layers of paint from dark underlayers to bright highlights.

For his famous candlelight and firelight scenes, he paid close attention to the way light emanates from a single source, illuminating nearby surfaces brightly while plunging surrounding areas into deep shadow. He carefully observed how light reflects off different materials – metal, glass, fabric, skin – and rendered these effects with great skill. His use of warm colours, particularly reds, oranges, and yellows, in the illuminated areas contrasts sharply with the cool blues, greys, and deep browns of the shadows, enhancing the visual impact.

While specific details about his pigment choices or canvas preparation are less documented than for some other artists, his paintings generally show a robust technique. His paint application could vary from smooth, detailed rendering in faces and key objects to broader, more suggestive brushwork in backgrounds or shadowy areas. He understood how to use texture, as well as tone and colour, to create convincing illusions of form and space within his dramatically lit compositions.

His dedication to capturing specific light effects, whether the harsh glare of a forge, the soft glow of moonlight, or the focused beam of a candle, was central to his artistic practice and remains one of the most compelling aspects of his work.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Joseph Wright of Derby occupies a unique and important place in British art history. He stands apart from the mainstream London-based portraitists and landscape painters of his generation due to his subject matter, his distinctive style, and his provincial base. His reputation rests primarily on his pioneering depiction of scientific and industrial themes and his extraordinary mastery of light effects.

He provided a powerful visual record of the Enlightenment and the early Industrial Revolution in Britain, capturing the excitement of scientific discovery and the awe-inspiring power of new technologies. His work reflects a shift in cultural values, where science and industry were gaining prestige and becoming worthy subjects for serious art.

While his direct influence on subsequent generations of painters may have been limited, partly due to his provincial location and independent stance, his achievements resonate with later developments in art. His dramatic use of light and his interest in sublime natural phenomena foreshadow aspects of Romanticism, particularly in the work of artists like Turner. His focus on contemporary life and labour can also be seen as anticipating aspects of 19th-century Realism.

Initially, his fame was somewhat eclipsed after his death, but his reputation underwent a significant revival in the 20th century. Art historians came to appreciate his originality, his technical skill, and his importance as a chronicler of a pivotal moment in history. Today, he is recognised as one of the most innovative and compelling British painters of the 18th century. His major works, like the Orrery and Air Pump, are considered icons of the Enlightenment era.

Conclusion: An Artist of Light and Progress

Joseph Wright of Derby was more than just a skilled painter; he was an artist deeply engaged with the intellectual and technological revolutions of his time. Through his canvases, illuminated by the dramatic interplay of light and shadow, he explored the wonders of science, the power of industry, and the enduring mysteries of the natural world. He gave visual form to the spirit of the Enlightenment, celebrating reason and discovery while also acknowledging the awe and sometimes unsettling implications of human progress. Rooted in his provincial home yet connected to the great minds of his age, Wright created a body of work that continues to fascinate and enlighten, securing his legacy as a truly original master of British art.