Aaron Harry Gorson, an artist whose name resonates with the dramatic grandeur of America's industrial age, carved a unique niche for himself in the annals of art history. He was a painter who found profound beauty and compelling narratives not in serene landscapes or classical allegories, but in the fiery heart of industrial might. His canvases, often depicting the steel mills of Pittsburgh under the cloak of night or the haze of dawn, are powerful testaments to an era of unprecedented technological advancement and the human endeavor that fueled it. This exploration delves into the life, artistic development, influences, key works, and enduring legacy of a painter who masterfully translated the raw, elemental power of industry into a compelling visual language.

From Lithuanian Roots to American Aspirations

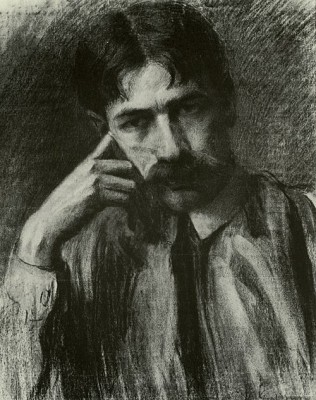

Aaron Harry Gorson's journey began far from the industrial landscapes he would later immortalize. Born in Kovno, Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire), in 1872, his early life was shaped by the cultural and socio-political currents of Eastern Europe. Like many Jewish families of that era, the Gorsons sought opportunities and refuge from the restrictive conditions prevalent in the Pale of Settlement. In 1888, at the age of sixteen, Gorson, along with his family, immigrated to the United States, settling in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This city, a burgeoning industrial center itself and a hub of artistic activity, would provide the initial backdrop for his American experience and the nascent stirrings of his artistic calling.

The transition to a new country, with its unfamiliar language and customs, was undoubtedly challenging. However, Philadelphia offered a vibrant environment. It was a city with a rich artistic heritage, home to institutions like the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, which played a pivotal role in shaping American art. Young Gorson, likely working various jobs to support himself and his family, began to nurture an interest in art. The precise moment or influence that sparked this passion is not extensively documented, but the cultural atmosphere of Philadelphia, with its museums and art schools, would have provided ample inspiration for a receptive mind.

His early years in America were formative, instilling in him the immigrant's drive and a keen observational eye. The contrast between the old world he had left behind and the dynamic, rapidly industrializing new world he now inhabited must have been stark. This period of adaptation and discovery laid the groundwork for his later artistic pursuits, even if the specific direction of his art was yet to be defined. The seeds of his unique vision were sown in these early experiences, absorbing the sights and sounds of a nation on the move, a nation forging its identity in the crucible of industry.

The Crucible of Formal Training: Philadelphia and Paris

Recognizing his artistic inclinations, Aaron Gorson pursued formal training to hone his skills. His first significant step was enrolling in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. Founded in 1805, PAFA was, and remains, one of America's most prestigious art institutions. Here, Gorson would have been immersed in a rigorous academic curriculum, focusing on drawing from casts, life drawing, and the principles of composition and painting. He studied at PAFA from 1894 to 1897, a period during which the institution was under the influence of prominent instructors who emphasized solid draftsmanship and a keen observation of reality.

One of the notable figures at PAFA during or around Gorson's time was Thomas Anshutz, a student and successor to the great realist Thomas Eakins. Anshutz, known for his own depictions of industrial scenes like "The Ironworkers' Noontime," continued Eakins' legacy of encouraging students to paint what they saw with honesty and precision. While the direct extent of Anshutz's influence on Gorson is speculative without detailed records of their interaction, the prevailing ethos at PAFA, which valued direct observation and engagement with contemporary American life, undoubtedly shaped Gorson's artistic outlook.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Gorson, like many aspiring American artists of his generation, traveled to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world at the turn of the 20th century. From 1897 to 1899, he immersed himself in the vibrant Parisian art scene. He studied at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe. At the Académie Julian, he received instruction from esteemed academic painters such as Jean-Paul Laurens and Benjamin Constant. These artists were masters of historical and allegorical painting, emphasizing strong composition, anatomical accuracy, and a polished finish.

Gorson also attended the Académie Colarossi, another popular alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. These Parisian academies provided a different flavor of instruction than PAFA, exposing him to European academic traditions and the latest artistic currents. More importantly, his time in Paris allowed him to witness firsthand the works of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas had revolutionized painting with their focus on light, color, and contemporary subject matter. The atmospheric effects and broken brushwork of Impressionism, as well as the nocturnal scenes of artists like James McNeill Whistler, would leave a lasting impression on Gorson, subtly influencing his later stylistic development.

The Pittsburgh Epiphany: A Muse of Fire and Steel

Upon his return to the United States around 1900, Gorson initially resided in Philadelphia and later New York. However, it was a pivotal move to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1903 that would define his artistic career and secure his legacy. Pittsburgh, at the dawn of the 20th century, was the undisputed heart of America's steel industry, a city of towering blast furnaces, sprawling mills, and a sky often aglow with the infernal light of molten metal. It was a landscape of raw, untamed industrial power, a place that many might have found grim or overwhelming, but for Gorson, it became a profound source of artistic inspiration.

He was not the first artist to depict industry, but Gorson approached the subject with a unique sensibility. He saw not just the grime and toil, but a dramatic, almost sublime beauty in the fiery spectacle of the mills, particularly at night or in the crepuscular hours of dawn and dusk. The interplay of artificial light from the furnaces with the natural light of the moon or the fading sun, the billowing smoke and steam creating atmospheric veils, the stark silhouettes of industrial structures against an illuminated sky – these became the signature elements of his work.

Gorson's decision to focus on Pittsburgh's industrial landscape was both bold and timely. The city was a symbol of American ingenuity and economic might, but its visual representation in fine art was relatively unexplored in the romantic, atmospheric way Gorson envisioned. He spent nearly two decades in Pittsburgh, from 1903 to 1921, and during this period, he tirelessly documented the mills along the Monongahela, Allegheny, and Ohio rivers. He would often venture out at night, sketching and absorbing the scenes, later translating these impressions onto canvas in his studio. His commitment to this subject matter was unwavering, establishing him as the preeminent painter of Pittsburgh's industrial inferno.

This period was incredibly prolific for Gorson. He developed a distinctive style that blended elements of Impressionism and Tonalism to capture the unique atmosphere of the steel city. His work resonated with audiences who saw in his paintings a reflection of the nation's industrial prowess, as well as a haunting, almost mystical beauty. The Pittsburgh years were not just a phase in Gorson's career; they were its defining chapter, where he found his true artistic voice and a subject matter that was uniquely his own.

Artistic Style: Forging a Vision in Light and Shadow

Aaron Harry Gorson’s artistic style is a fascinating amalgamation of various influences, masterfully adapted to suit his chosen subject matter: the industrial landscape. While he received academic training both in Philadelphia and Paris, his mature style moved beyond strict academicism, embracing more contemporary approaches to light, color, and atmosphere. His work is often categorized within the realms of American Impressionism and Tonalism, with some affinities to the urban realism of the Ashcan School, though his focus was less on social commentary and more on the aesthetic and atmospheric qualities of the industrial scene.

A key characteristic of Gorson's style is his masterful handling of light, particularly in his nocturnal and twilight scenes. He was captivated by the dramatic effects of artificial light emanating from the steel mills – the fiery glow of furnaces, the sparks of welding, the reflections on wet surfaces – contrasted with the softer, more diffused light of the moon or the fading day. This fascination with light echoes the concerns of the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet, who meticulously studied the changing effects of light on various subjects. Gorson, however, applied these principles to a far grittier, man-made environment.

His palette often leaned towards the Tonalist sensibility, characterized by a limited range of colors, subtle gradations of tone, and an emphasis on mood and atmosphere. Artists like James McNeill Whistler, famous for his "Nocturnes," were pioneers of Tonalism, and Gorson's own nocturnal industrial scenes share a similar poetic and evocative quality. He frequently employed deep blues, purples, grays, and blacks, punctuated by the vibrant oranges, yellows, and reds of the industrial fires. This created a powerful contrast and a sense of drama, transforming the mundane into the magnificent.

Gorson's brushwork, while not as broken or staccato as some of the French Impressionists, often had a painterly quality, allowing the texture of the paint and the energy of his strokes to contribute to the overall effect. He was adept at capturing the ephemeral qualities of smoke, steam, and mist, which often shrouded his industrial subjects, adding to their mystery and grandeur. While the Ashcan School artists, like Robert Henri or John Sloan, depicted the gritty reality of urban life, Gorson's industrial scenes, though realistic in their depiction of structures and processes, often transcended mere documentation, imbuing the industrial landscape with a sense of awe and an almost romantic sensibility. His unique synthesis of these stylistic elements allowed him to create a body of work that was both a record of its time and a timeless artistic statement.

Masterworks of the Monongahela: Key Paintings and Themes

Throughout his prolific Pittsburgh period, Aaron Harry Gorson produced a significant body of work that captured the essence of the industrial heartland. While specific titles might vary in records or have been reused for similar compositions, his oeuvre is characterized by recurring themes and a consistent vision. His most iconic paintings are undoubtedly those depicting the steel mills along the Monongahela River, often under the dramatic illumination of night.

One common subject, appearing in various iterations, is "Pittsburgh Steel Mills at Night" or "Monongahela River Scene." These paintings typically feature the dark, imposing silhouettes of factory buildings, smokestacks, and bridges set against a sky lit by the fiery discharge of the furnaces. The reflections of these intense lights on the surface of the river are a hallmark of Gorson's work, creating a shimmering, almost ethereal counterpoint to the solidity of the industrial structures. The water, often dark and mysterious, acts as a mirror, doubling the drama of the scene and adding depth to the composition.

In works like "Nocturne, Pittsburgh," the influence of Whistler is palpable, yet Gorson's subject matter is distinctly American and industrial. He masterfully balances the somber tones of the night with the brilliant, almost explosive bursts of light from the mills. The human element is often absent or minimized in these scenes; the focus is on the overwhelming power and scale of industry itself, presented as a force of nature, both beautiful and terrifying. The smoke and steam, rendered with a soft, atmospheric touch, contribute to the sense of mystery and dynamism, as if the mills themselves are living, breathing entities.

Another recurring theme is the depiction of the mills from a distance, often incorporating elements of the surrounding landscape or the city. These compositions emphasize the integration of industry into the urban fabric and the natural environment, highlighting its pervasive presence. Gorson was not merely painting factories; he was painting a specific place and time, capturing the unique character of Pittsburgh as the "Steel City." His works convey a sense of awe at the technological prowess and relentless energy of the industrial age.

Beyond the purely visual, Gorson's paintings evoke a complex range of emotions. There is a sense of grandeur and power, but also a hint of melancholy, perhaps reflecting the human cost and environmental impact of such intense industrial activity. His ability to find beauty in such an unlikely subject, to transform the gritty reality of the mills into scenes of poetic and dramatic power, is what distinguishes his work. These paintings are not just historical documents; they are profound artistic statements about the nature of modernity and the human capacity to reshape the world. His contemporary, Joseph Pennell, also explored industrial themes, particularly in his etchings, but Gorson's lush, painterly approach to the fiery spectacle was unique.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Critical Acclaim

Aaron Harry Gorson's distinctive and powerful depictions of industrial Pittsburgh did not go unnoticed in the art world. Throughout his career, he actively exhibited his work, gaining recognition and critical acclaim. His paintings were regularly accepted into prestigious annual exhibitions at major American art institutions, which were crucial venues for artists to showcase their talents and reach a wider audience.

Gorson frequently exhibited at the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, one of the most important contemporary art exhibitions in the United States at the time. His participation in these exhibitions, starting as early as 1904, placed his work alongside that of leading American and European artists, signifying his growing stature. The fact that he was depicting the very industrial landscape that fueled Pittsburgh's prosperity likely resonated with local audiences and patrons. His work offered a unique artistic perspective on the city's identity.

He also showed his paintings at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) annual exhibitions, a significant platform for American artists. His connection to PAFA as an alumnus and his consistent participation in its exhibitions helped solidify his reputation within the broader American art scene. Furthermore, Gorson exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York, another key institution that played a vital role in shaping American art. His inclusion in their exhibitions demonstrated that his work was recognized beyond Pittsburgh, appealing to a national audience.

Other notable venues where Gorson's work was displayed include the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Art Institute of Chicago. These exhibitions exposed his unique vision to critics, collectors, and the general public across the country. While he may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as some of his contemporaries who focused on more traditional subjects, like the American Impressionists Childe Hassam or John Henry Twachtman, Gorson carved out a significant reputation as a specialist in industrial scenes.

Critical reception of Gorson's work was generally positive. Reviewers often commented on his ability to capture the dramatic beauty and sublime power of the industrial landscape, particularly his atmospheric nocturnal scenes. His technical skill in rendering the effects of light and smoke, and his unique choice of subject matter, were frequently praised. He was seen as an artist who had found a truly American subject and depicted it with originality and artistic integrity. This recognition, demonstrated through consistent exhibition opportunities and favorable reviews, affirmed his place as an important chronicler of the American industrial age.

Gorson and His Contemporaries: A Shared Zeitgeist

Aaron Harry Gorson operated within a rich and diverse American art scene at the turn of the 20th century. While his primary focus on industrial nocturnes set him apart, his work can be understood in the context of broader artistic movements and the preoccupations of his contemporaries. His training under figures like Thomas Anshutz at PAFA connected him to a lineage of American realism that valued direct observation and engagement with contemporary life. Anshutz himself, with works like "The Ironworkers' Noontime," demonstrated an interest in industrial labor, a theme that Gorson would later explore from a different, more atmospheric perspective.

In Paris, his exposure to academic masters like Jean-Paul Laurens and Benjamin Constant provided a strong foundation in traditional techniques. However, the pervasive influence of Impressionism, with artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro revolutionizing the depiction of light and atmosphere, undoubtedly impacted Gorson's approach. While not a strict Impressionist, Gorson adopted their sensitivity to light and their painterly brushwork, adapting these techniques to his unique subject matter.

The influence of James McNeill Whistler is particularly evident in Gorson's nocturnal scenes. Whistler's "Nocturnes," with their Tonalist palette and emphasis on mood and atmosphere, provided a precedent for finding aesthetic beauty in urban and industrial settings at night. Gorson extended this sensibility to the fiery, dynamic environment of the Pittsburgh steel mills, creating a distinctly American version of the nocturne.

Gorson's work also shares some affinities with the Ashcan School, a group of artists that included Robert Henri, John Sloan, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and William Glackens. These artists were committed to depicting the realities of modern urban life, often focusing on the grittier aspects of the cityscape and its inhabitants. While Gorson's paintings were generally less focused on social commentary or the human figure, his choice of the industrial landscape as a primary subject aligned with the Ashcan School's interest in contemporary, often unglamorous, American scenes. He, like them, found artistic inspiration in the rapidly changing urban environment.

Other artists of the period also engaged with industrial themes. Joseph Pennell, for instance, created powerful etchings and lithographs of industrial sites, including Pittsburgh. However, Gorson's approach, with its emphasis on color, light, and the painterly qualities of oil, offered a different, often more romanticized, vision of industry. His contemporaries among American Impressionists, such as Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, or John Henry Twachtman, typically focused on more genteel urban scenes, landscapes, or domestic interiors. Gorson's dedication to the industrial sublime carved out a unique path, positioning him as a singular voice capturing a crucial aspect of the American experience.

The New York Years and Continued Vision

In 1921, after nearly two decades of intensely focusing on the industrial landscapes of Pittsburgh, Aaron Harry Gorson made a significant change in his life by relocating to New York City. This move marked a new chapter, though his artistic preoccupation with the themes that had defined his Pittsburgh period did not entirely cease. New York, a metropolis of a different kind – a vertical city of skyscrapers, bustling harbors, and iconic bridges – offered new visual stimuli, yet the allure of the industrial scene, particularly its nocturnal drama, remained a powerful force in his work.

While in New York, Gorson continued to paint and exhibit. He found new subjects in the city's impressive architectural feats and its vibrant energy, but he also revisited his signature industrial themes, perhaps drawing on his vast repository of sketches and memories from Pittsburgh, or finding new industrial subjects in and around the New York metropolitan area. The fundamental elements of his style – the Tonalist palette, the Impressionistic handling of light, and the focus on atmospheric effects – remained consistent.

His reputation as a painter of industrial America was well-established by this time, and his works continued to be sought after by collectors and exhibited in galleries. The move to New York placed him at the center of the American art world, providing more opportunities for exhibition and interaction with other artists. However, the core of his artistic identity had been forged in the fiery mills of Pittsburgh, and this remained his most recognized and celebrated contribution.

The 1920s and early 1930s saw shifts in the American art scene, with the rise of movements like Precisionism, which also depicted industrial subjects but with a cleaner, more geometric aesthetic (exemplified by artists like Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler), and later, Regionalism. Gorson, however, largely remained true to the stylistic path he had established, a path that blended realism with a romantic, atmospheric sensibility. His work offered a more emotive and less clinical view of industry compared to the Precisionists.

Aaron Harry Gorson continued to paint until his death in New York City on October 11, 1933. He left behind a substantial body of work that stands as a powerful and poetic testament to America's industrial age. His later years in New York, while perhaps less intensely focused on a single geographical location than his Pittsburgh period, were a continuation of his lifelong artistic quest to capture the dramatic beauty and awe-inspiring power of the modern, man-made landscape.

Legacy and Enduring Impact: Illuminating the Industrial Soul

Aaron Harry Gorson's legacy is firmly anchored in his evocative and powerful depictions of the American industrial landscape, particularly the steel mills of Pittsburgh. He holds a distinct place in American art history as one of the foremost painters to find profound aesthetic and emotional resonance in subjects that many of his contemporaries might have overlooked or considered unpicturesque. His work serves as a vital visual record of a transformative era in American history, capturing the zeitgeist of a nation flexing its industrial muscle.

His paintings are held in the collections of numerous prestigious museums, including the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, which possesses a significant collection of his work, appropriately so given his deep connection to the city. Other institutions such as the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio, and various private collections also house his paintings. The presence of his work in these collections ensures its accessibility to future generations and its continued study by art historians and enthusiasts.

Gorson's unique contribution lies in his ability to synthesize elements of Impressionism and Tonalism to create a visual language perfectly suited to his industrial subjects. He transcended mere documentation, imbuing his scenes with a sense of drama, mystery, and an almost sublime beauty. His nocturnal views, with their fiery glows, deep shadows, and atmospheric veils of smoke and steam, are particularly iconic. They capture not just the physical reality of the mills, but also their symbolic power as crucibles of modernity.

In an era when many American artists were still looking to European traditions or idyllic landscapes for inspiration, Gorson embraced a quintessentially American subject. His work can be seen as a precursor to later artistic explorations of industrial themes, though his romantic and atmospheric approach remains distinctive. He provided an alternative to the more critical or purely documentary views of industry, finding a poetic grandeur in its operations.

The enduring appeal of Gorson's work lies in its ability to evoke a sense of awe and wonder at the transformative power of human endeavor, while also hinting at the inherent drama and perhaps even the underlying anxieties of the industrial age. He was a visual poet of the factory, a bard of the blast furnace, and his canvases continue to resonate with their powerful depiction of an America forged in fire and steel. His art remains a testament to the fact that beauty can be found in the most unexpected of places, and that the human spirit, in its quest to build and innovate, creates landscapes worthy of artistic celebration.

Conclusion: The Alchemist of Industry

Aaron Harry Gorson stands as a significant figure in American art, an artist who dared to look into the fiery heart of industry and extract from it a profound and compelling beauty. From his immigrant beginnings to his dedicated pursuit of artistic training in Philadelphia and Paris, and ultimately to his defining years in Pittsburgh, Gorson's journey was one of focused vision and artistic integrity. He did not shy away from the raw, often harsh, reality of the industrial landscape but instead transformed it through his unique artistic lens, revealing its dramatic grandeur, its atmospheric mysteries, and its symbolic power.

His masterful use of light and shadow, his Tonalist palette punctuated by incandescent bursts of color, and his ability to capture the ephemeral qualities of smoke and steam, all contributed to a body of work that is both a historical document and a timeless artistic achievement. He remains celebrated for his nocturnal scenes of the steel mills, which possess a haunting, almost sublime quality, elevating the industrial subject to the realm of high art. Through his canvases, Aaron Harry Gorson offered a unique perspective on the American experience at the height of its industrial might, leaving behind a legacy that continues to illuminate the soul of an era. His work reminds us that art can find its muse anywhere, even in the most formidable and seemingly unpoetic corners of the modern world.