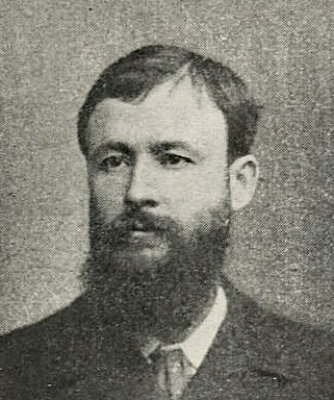

Joseph Bail (1862-1921) stands as a significant figure in French painting during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Working within the Realist and Naturalist traditions, he carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming renowned for his intimate portrayals of domestic life, particularly kitchen and interior scenes, and his exceptional skill in rendering the effects of light. Born into an artistic family and trained under prominent masters, Bail navigated the complex art world of his time, achieving considerable success and leaving behind a body of work celebrated for its technical brilliance and quiet charm.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Joseph Bail was born in Limonest, near Lyon, in the Rhône department of France, in 1862. His artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age, heavily influenced by his father, Jean-Antoine Bail. The elder Bail was himself a painter, specializing in genre scenes and known for his admiration of the Dutch Golden Age masters. He instilled in Joseph an appreciation for meticulous observation and the depiction of everyday life, guiding his early artistic development.

This familial environment was steeped in art. Jean-Antoine Bail not only taught Joseph the fundamentals but also encouraged his interest in the works of the great 18th-century French painter Jean-Siméon Chardin, whose quiet domestic scenes and masterful still lifes would become a lifelong inspiration for Joseph. The Bail family, including Joseph's brother Frank Bail who also became a painter, represented a continuation of the Realist tradition in French art during a period increasingly dominated by newer movements. Joseph showed early promise, exhibiting a still life painting at the prestigious Paris Salon at the young age of sixteen.

Formal Training and Key Influences

Seeking to refine his skills further, Joseph Bail moved to Paris and undertook formal training between 1879 and 1880. He studied under the tutelage of Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most prominent academic painters of the era. Gérôme was celebrated for his highly polished technique, historical subjects, and Orientalist scenes. While Bail's subject matter would differ significantly from his master's, Gérôme's emphasis on precise drawing, careful composition, and finished surfaces undoubtedly reinforced Bail's own inclination towards detailed realism.

Beyond Gérôme, Bail absorbed lessons from other contemporaries and historical figures. The influence of Carolus-Duran (Charles-Émile-Auguste Durand), another leading figure known for his portraiture and realist tendencies, can also be discerned. However, the foundational influences remained those fostered by his father: the intimate domesticity and luminous still lifes of Jean-Siméon Chardin, and the atmospheric interiors and light effects of Dutch masters like Johannes Vermeer. Bail synthesized these influences, developing a style that was both technically accomplished and deeply personal. He also looked towards contemporary Realists like Théodore Ribot and François Bonvin, who similarly found beauty and significance in humble subjects and employed strong chiaroscuro effects.

The Allure of the Everyday: Domestic Interiors

Joseph Bail is perhaps best known for his captivating depictions of domestic interiors, particularly kitchens, sculleries, and pantries. These were not scenes of aristocratic grandeur, but rather the quiet, working spaces of bourgeois households. His canvases are often populated by young women – maids, cooks, or seamstresses – engaged in simple, everyday tasks: polishing copper pans, preparing food, inspecting linen, or pausing for a moment of reflection.

There is a profound sense of tranquility and order in these scenes. Bail elevates the mundane, finding dignity and beauty in domestic labor. The figures are rendered with sensitivity, often absorbed in their work, contributing to the peaceful atmosphere. Unlike some social realists who might highlight hardship, Bail's focus seems to be on the harmony and quiet rhythm of household life. His approach recalls the spirit of Dutch Golden Age painters such as Pieter de Hooch or Gabriel Metsu, who similarly celebrated the virtues of domesticity through carefully observed interior scenes.

Mastery of Light and Shadow

A defining characteristic of Joseph Bail's art is his extraordinary ability to capture the play of light. He frequently employed strong light sources, often emanating from a window just outside the picture frame or a strategically placed lamp within the scene. This allowed him to utilize chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – to define forms, create depth, and imbue his paintings with a palpable atmosphere.

Light in Bail's paintings does more than simply illuminate; it reveals texture and substance. It gleams on polished copper pots (a recurring and signature motif), reflects softly off ceramic jugs, catches the folds in starched white linen, and models the features of his figures. His handling of light is often compared to that of Vermeer and Chardin. Like Vermeer, he could capture the subtle diffusion of light in an interior space, creating a sense of stillness and intimacy. Like Chardin, his light often seems to caress objects, revealing their inherent beauty and solidity. This mastery of light transforms ordinary scenes into visually compelling compositions, drawing the viewer into the quiet world he depicts.

Still Life Painting

Joseph Bail's artistic journey began with still life, and it remained an important genre for him throughout his career. His skills honed in depicting inanimate objects are evident even in his more complex interior scenes. His still lifes typically feature arrangements of kitchenware, food items, and sometimes game. Copper pots and pans, earthenware jars, gleaming glassware, eggs, vegetables, and textiles are rendered with meticulous attention to detail and texture.

His approach to still life shares much with Chardin, emphasizing the humble beauty of everyday objects through careful arrangement and sensitive handling of light and paint. Works like Still Life with Egg exemplify his ability to give presence and weight to simple items, making the viewer appreciate their form, color, and surface texture. There is often a trompe-l'oeil quality to his still lifes, a convincing realism that makes the objects seem almost tangible. This dedication to the faithful representation of reality was a hallmark of his artistic philosophy.

Genre Scenes and Narrative

While many of his works focus on single figures in quiet interiors, Bail also painted genre scenes that imply simple narratives or capture fleeting moments of interaction. Cats Playing Around a Mirror, for instance, introduces a playful element into the domestic setting, showcasing his ability to observe and render animals with the same care he devoted to human figures and objects. These works often maintain the same intimate scale and focus on everyday life that characterize his broader oeuvre.

His brother, Frank Bail, often explored similar themes, and the Bail brothers sometimes exhibited works together at the Salon, reinforcing the family's association with this particular vein of Realist genre painting. Joseph's genre scenes, like his interiors and still lifes, avoid high drama or complex allegory, preferring instead to find meaning and beauty in the familiar and the observable.

Career Success and Recognition

Joseph Bail achieved considerable success during his lifetime. He was a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, the premier venue for artists seeking official recognition and patronage. His work garnered positive critical attention and numerous accolades. He received honorable mentions and medals at the Salons of the 1880s and 1890s, including specific recognition in 1894 and 1897.

His reputation was further solidified by major awards at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris. He won a silver medal in 1889 and, significantly, Gold Medals in both 1900 and 1902. These awards cemented his status as a leading painter within the established art system. His work found favor with middle-class collectors who appreciated his technical skill, familiar subject matter, and the sense of order and nostalgia his paintings often evoked. Government purchases for provincial museums also likely occurred, a common form of patronage for successful Salon artists of the period.

Context: Realism in an Age of Change

Joseph Bail practiced his art during a period of immense artistic ferment in France. While he adhered to the principles of Realism and Naturalism, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed the rise of revolutionary movements that challenged traditional artistic conventions. Impressionism, spearheaded by artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, had already shifted focus towards capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and color, and scenes of modern life, often using looser brushwork.

Following the Impressionists came the Post-Impressionists, including Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Paul Cézanne, each pushing art in new directions, exploring emotional expression, symbolic color, scientific theories of optics, or the underlying structure of form. Concurrently, the foundations of Modernism were being laid.

Within this dynamic context, Bail represented a more conservative, albeit highly skilled, approach. His meticulous technique, traditional subject matter, and adherence to representational accuracy aligned him with the academic tradition favored by the official Salon, even as that institution faced increasing challenges from the avant-garde. His work, alongside that of other successful Naturalists like Jules Bastien-Lepage or Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, appealed to a public and a critical establishment that valued craftsmanship and familiar themes. In an era of rapid industrialization and social change, Bail's paintings offered glimpses into a seemingly stable, ordered, and often nostalgic vision of domestic life, providing a comforting counterpoint to the perceived disruptions of modernity.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

Joseph Bail died in 1921. He is remembered as a master technician, particularly admired for his handling of light and his ability to render textures convincingly. While not an avant-garde innovator who radically altered the course of art history, he was a highly accomplished painter who excelled within his chosen field of Realist genre painting and still life.

His significance lies in his skillful continuation and adaptation of the tradition inherited from Chardin and the Dutch Masters. He brought their focus on domestic intimacy and the beauty of the everyday into the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, creating works that resonated with the tastes and values of his time. His paintings remain appealing for their technical virtuosity, their serene atmosphere, and their sensitive portrayal of simple moments. Though perhaps overshadowed in broader art historical narratives by the rise of Modernism, Joseph Bail holds a secure place as a distinguished exponent of French Realism, a painter whose dedication to craft and quiet observation produced a legacy of enduring charm.

Conclusion

Joseph Bail's art offers a window into the tranquil corners of domestic life at the turn of the twentieth century. Through his masterful control of light, meticulous attention to detail, and sensitive portrayal of everyday scenes, he created a body of work that celebrates the beauty found in simplicity and order. As a successor to the great traditions of Chardin and the Dutch genre painters, and a respected figure in the French art world of his day, Bail's paintings continue to captivate viewers with their technical brilliance and serene, intimate vision. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman and a keen observer who found profound beauty in the quiet rhythms of the everyday world.