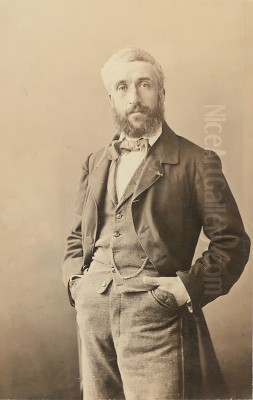

Philippe Rousseau stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. Born in Paris in 1816 and passing away in Acquigny in 1887, his career spanned a period of immense artistic change, witnessing the flourishing of Romanticism, the rise of Realism and the Barbizon School, and the dawn of Impressionism. While associated with these currents, Rousseau carved a distinct niche for himself, primarily celebrated for his exquisite still life paintings and engaging animal scenes, often imbued with narrative charm.

He emerged not from the formal structure of the École des Beaux-Arts, but through apprenticeship, a common path at the time. His initial training under the landscape painter Victor Bertin provided him with a solid foundation. Bertin, a follower of the Neoclassical landscape tradition, likely instilled in Rousseau a respect for structure and careful observation, even as Rousseau's own path diverged significantly from his master's style.

Early Career and Salon Debut

Rousseau made his first appearance at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1834. This annual exhibition was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their careers. In these early years, Rousseau, perhaps reflecting his training with Bertin, focused primarily on landscape painting. However, his artistic inclinations soon began to shift.

The landscapes gave way to a deeper exploration of more intimate subjects. He turned his attention towards still life and the depiction of animals, genres that would come to define his artistic identity. This transition marked the beginning of his journey towards becoming one of the most respected specialists in these fields during his time.

The Influence of Chardin and the Still Life Revival

A pivotal aspect of Rousseau's development was his deep admiration for the 18th-century master Jean-Siméon Chardin. Chardin was renowned for his quiet, contemplative still lifes and genre scenes, celebrated for their masterful handling of light, texture, and composition, elevating everyday objects to subjects of profound artistic meditation. In the mid-19th century, there was a renewed appreciation for Chardin's work, often termed the "Chardin Revival."

Philippe Rousseau became a key figure associated with this revival. He absorbed Chardin's lessons in rendering textures – the gleam of copper, the softness of fur, the translucence of glass – and the arrangement of objects in harmonious, often simple, compositions. However, Rousseau did not merely imitate. He brought his own sensibility, often incorporating a greater sense of abundance or narrative suggestion into his still lifes compared to Chardin's more austere arrangements. Another 18th-century artist, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, known for his hunting scenes, animal portraits, and decorative still lifes, also served as an important precedent for Rousseau's work, particularly in the depiction of game and animals within still life contexts.

His still life works often feature kitchen settings, arrangements of fruits, vegetables, game, and tableware. He displayed a remarkable ability to capture the materiality of objects, making them almost tangible to the viewer. This dedication to realistic representation, combined with a subtle compositional elegance, earned him considerable acclaim. He found a ready market for these works among the bourgeoisie, who appreciated their technical skill and domestic appeal. Artists like Antoine Vollon were contemporaries also excelling in the still life genre, creating a vibrant context for this type of painting.

Master of Animal Painting: Observation and Narrative

Alongside still life, Philippe Rousseau excelled in animal painting. He moved beyond simple animal portraiture to create scenes brimming with life and often, a gentle humour or narrative derived from literary sources. He was particularly adept at capturing the character and behaviour of animals, from playful kittens and loyal dogs to more exotic creatures.

A significant portion of his animal works drew inspiration from the famous Fables of Jean de La Fontaine. These 17th-century poems, using animal characters to convey moral lessons, provided Rousseau with rich source material. He translated these literary vignettes into visual form, skillfully integrating animals into settings that enhanced the story.

His 1845 Salon entry, The City Rat and the Country Rat (Le Rat de ville et le rat des champs), based on La Fontaine's fable contrasting simple country life with the precarious luxury of the city, was a critical success. It showcased his ability to combine meticulous still life elements (representing the feast) with expressive animal depiction (the contrasting characters of the rats). This work cemented his reputation as a leading painter in this specialized genre.

Other works likely inspired by fables include paintings depicting scenes like The Fox and the Stork. These paintings allowed Rousseau to display not only his technical prowess in rendering fur and feathers but also his talent for visual storytelling, capturing the essence of the fable's narrative and moral through the animals' interactions and expressions. He wasn't merely painting animals; he was painting animal characters within a story. This narrative focus distinguished his work from purely anatomical or zoological studies, aligning him more with a tradition that saw animals as actors in allegorical scenes.

His skill extended to various animals. He painted dogs and cats with particular frequency, often capturing their domestic interactions. A notable commission mentioned involved a large painting featuring dogs and cats, possibly Le Chien et le Chat, intended for the state collections around 1850, likely destined for the Musée du Luxembourg, the contemporary art museum of its day, whose collections later partially formed the basis of the Musée d'Orsay.

He also depicted birds with great skill. A work often cited is his painting featuring flamingoes, sometimes referred to as Flamingoes in a Landscape (Flamants dans un paysage), dated to 1863. This work, potentially executed in mixed media including watercolour and charcoal, highlights his ability to capture the elegance and distinctive form of these birds within a naturalistic setting, possibly alongside other creatures like peacocks, showcasing his versatility beyond domestic animals and fable illustrations.

Connection to the Barbizon Sphere and Landscape

While Philippe Rousseau specialized in still life and animals, his connection to the broader art world, particularly the Barbizon School, is noteworthy, primarily through his brother, Théodore Rousseau. Théodore was a central figure, arguably the leader, of the Barbizon School, a group of artists who rejected Neoclassical formalism and Romantic melodrama to paint landscapes directly from nature in the Forest of Fontainebleau, near the village of Barbizon.

Artists like Jean-François Millet, Camille Corot, and Charles-François Daubigny were key members of this group, emphasizing realistic depiction, the effects of light and atmosphere, and often, the dignity of rural life. While Philippe shared the era's growing interest in naturalism and detailed observation, his primary focus remained distinct from the core Barbizon preoccupation with pure landscape.

However, Philippe was undoubtedly familiar with the Barbizon artists and their ideals through his brother. He sometimes incorporated landscape elements into his animal paintings, providing naturalistic settings for his subjects, as seen in the Flamingoes painting. He maintained a connection to this circle, exhibiting alongside them and sharing certain naturalist sensibilities. But classifying him as a Barbizon painter is inaccurate; his studio-based focus on still life and narrative animal scenes sets him apart from the plein-air landscape focus of Millet or Théodore Rousseau.

Style, Technique, and Recognition

Philippe Rousseau's style is characterized by meticulous realism, a rich palette, and a keen eye for texture and detail. His technique often involved smooth brushwork, allowing for precise rendering, particularly in still lifes where the surfaces of objects were paramount. He demonstrated a mastery of light, using it to model forms and create atmosphere, whether it be the cool light of a larder or the warm glow on a piece of fruit.

His compositions are typically well-balanced and carefully arranged, even when depicting seemingly casual scenes. There's an underlying structure that guides the viewer's eye. While influenced by Chardin and Oudry, echoes of Dutch Golden Age masters, known for their detailed still lifes and animal paintings (artists like Jan Weenix or Melchior d'Hondecoeter come to mind), can also be discerned in his work's precision and subject matter.

Despite not following a traditional academic path, Rousseau achieved significant recognition through the Salon system. While he may have faced occasional rejection, a common experience for artists navigating the Salon juries, his work was frequently exhibited and generally well-received by critics and the public, particularly from the 1840s onwards. His success culminated in official honours, including being awarded the Legion of Honour in 1870, a significant mark of state recognition for his artistic contributions.

He navigated the art market successfully, likely working with influential dealers of the period. Figures like Paul Durand-Ruel, who famously supported the Barbizon painters and later the Impressionists, were active during Rousseau's mature career, shaping the market for contemporary French art. Rousseau's appealing subject matter and technical skill made his work desirable to collectors.

Distinctions and Historical Context

It is crucial to distinguish Philippe Rousseau from two other famous artists named Rousseau. He is distinct from his brother, the landscape painter Théodore Rousseau, despite their familial and artistic connections. He is also entirely separate from Henri 'Le Douanier' Rousseau, the later Post-Impressionist/Naïve painter known for his stylized jungle scenes, whose career began shortly before Philippe's death and whose style is vastly different.

Philippe Rousseau worked during a period dominated by major artistic figures and movements. Gustave Courbet championed Realism with a more rugged, socially conscious approach. The Barbizon painters redefined landscape art. Later in Rousseau's career, Impressionism emerged, with artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas revolutionizing the depiction of light and modern life.

Rousseau's art exists somewhat apart from these dominant trends, yet it reflects the era's broader interest in realism and observation. He represents a continuation and revitalization of the esteemed traditions of French still life and animal painting, adapting them to 19th-century tastes. His focus on narrative, particularly drawing from La Fontaine, also connects him to a long tradition of didactic and allegorical art. He can be seen alongside other skilled animaliers of the time, such as Constant Troyon (who also had Barbizon connections but became famous for his cattle paintings) and Jacques Raymond Brascassat.

Legacy

Philippe Rousseau died in Acquigny, Normandy, in 1887. He left behind a substantial body of work characterized by technical refinement, careful observation, and narrative charm. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, he was a master within his chosen genres. His paintings offer a window into the tastes and sensibilities of the 19th century, particularly the appreciation for finely rendered depictions of the natural world and domestic life.

His role in the Chardin Revival highlights his connection to art history and his contribution to maintaining the vitality of the still life tradition. His animal paintings, especially those illustrating fables, showcase a unique blend of realism and storytelling that captivated his audience. Today, his works are held in numerous museums in France and internationally, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, testifying to his enduring appeal and his secure place within the history of 19th-century French art as a specialist of considerable talent and distinction. He remains a testament to the diverse artistic paths pursued during a dynamic period, celebrated for his dedication to capturing the beauty and character of the world's details, both animate and inanimate.