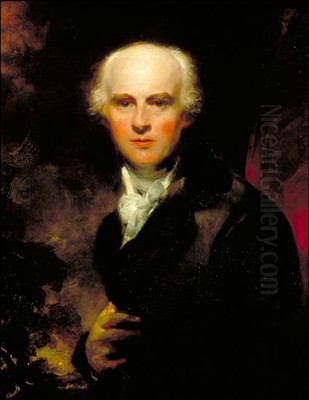

Joseph Farington (1747-1821) stands as a significant, if sometimes underestimated, figure in the landscape of late 18th and early 19th-century British art. While his reputation as a painter of carefully rendered topographical views is secure, his enduring legacy is perhaps even more powerfully cemented by his meticulous and voluminous diary. This remarkable document offers an unparalleled window into the London art world, its personalities, its politics, and its daily machinations, making Farington not only an artist in his own right but also one of the most important chroniclers of his artistic generation. His life and work provide a fascinating intersection of artistic practice, institutional involvement, and social observation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Leigh, Lancashire, in 1747, Joseph Farington's path into the world of art began with a foundational apprenticeship. He was fortunate to study under Richard Wilson, a pioneering figure in British landscape painting, often hailed as one of the fathers of the genre in Britain. Wilson, known for his classical, Italianate landscapes, would have instilled in Farington a respect for structured composition and the careful observation of nature, albeit often filtered through an Arcadian lens. This tutelage, commencing around 1763, provided Farington with the essential skills and artistic grounding that would shape his subsequent career.

The establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1768 marked a pivotal moment for British art, and Farington was among its earliest beneficiaries. He became one of the first students to enroll, immersing himself in an environment dedicated to elevating the status of art and artists in Britain. The Academy, under its first president Sir Joshua Reynolds, aimed to provide systematic training and a prestigious platform for exhibition. Farington's association with the Royal Academy would become a defining feature of his life. He formally joined the institution in 1769 and, through diligence and a keen understanding of its workings, was elected an Academician (RA) in 1785, a testament to his standing among his peers.

The Landscape Artist: Depicting Britain's Scenery

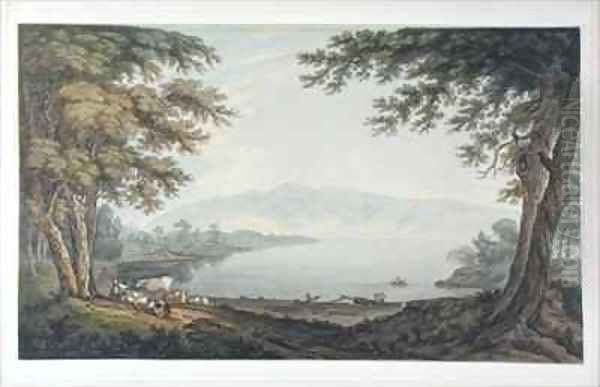

Farington's primary artistic output was in the realm of landscape and topographical drawing and painting. He developed a reputation for accurate and detailed representations of specific locales, a skill highly valued in an era before photography. His work often focused on the British countryside, with a particular affinity for the picturesque and the historically significant. He was less concerned with the sublime, dramatic interpretations of nature that would come to characterize the work of younger Romantics like J.M.W. Turner, and more focused on a faithful, if aesthetically pleasing, record of place.

His style was characterized by careful draughtsmanship, often employing a base of pencil drawing overlaid with delicate washes of watercolor, typically in muted tones of blue-grey to define forms. Ink was then used with a fine pen or brush to delineate details and strengthen outlines. This methodical approach, while perhaps lacking the expressive dynamism of some of his contemporaries, resulted in works of considerable charm and informational value. There's an undeniable influence of earlier topographical traditions, and even echoes of masters like Canaletto in the precision of his architectural elements, though applied to a British context.

Masterpieces in Print: Lakes, Rivers, and Views

While Farington exhibited paintings at the Royal Academy, a significant portion of his artistic reputation during his lifetime, and indeed since, rests on his published collections of views. These volumes brought his art to a wider audience and contributed to the growing appreciation for British scenery.

One of his most notable achievements in this area was Views of the Lakes of Cumberland and Westmorland, first published in 1785 and reissued in 1816. The Lake District was becoming an increasingly popular destination for tourists seeking the picturesque, a trend fueled by writers like William Gilpin. Farington's views provided visual accompaniments to this burgeoning interest, capturing the serene beauty of locations such as Derwentwater and Windermere. His work Skiddaw & Derwent Water is a fine example of his ability to combine topographical accuracy with a pleasing compositional arrangement. These images helped to solidify the Lake District's place in the national consciousness as a region of outstanding natural beauty.

Another major project was his contribution to A History of the River Thames, published in two volumes between 1794 and 1796, for which he provided numerous illustrations. This ambitious work documented the course of the river, its landmarks, and its associated history. Farington's drawings for this publication showcased his skill in rendering varied landscapes, from rural stretches to views incorporating towns and grand estates along the Thames. These works are invaluable records of the river's appearance at the turn of the 19th century.

Other specific works further illustrate his topographical skill. For instance, Castle-Awe Abbey, West View, Norfolk (1816) demonstrates his continued engagement with architectural subjects within a landscape setting, while an unfinished piece like Cottage and Outbuildings by a River (circa 1790) offers insight into his working methods, revealing the underlying structure and initial washes before the final detailed rendering.

The Diarist: A Window into an Age

Beyond his artistic output, Joseph Farington's most enduring contribution to art history is undoubtedly his diary. Commenced in 1793 and maintained with remarkable consistency until his death in 1821, this extensive journal runs to sixteen published volumes. It is an unparalleled primary source for understanding the London art world of the period, offering intimate glimpses into the lives, opinions, and professional dealings of a vast array of artists, patrons, and cultural figures.

Farington meticulously recorded his daily activities, conversations, and observations. He noted who he dined with, what was discussed, the gossip of the Royal Academy, the prices fetched by artworks, the progress of commissions, and the critical reception of exhibitions. His entries cover debates within the Academy, the financial struggles of fellow artists, the political news of the day – including the profound impact of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars – and even details about health and medicine, such as his notes on Dr. Edward Jenner and the reception of his vaccination discoveries.

The diary is not merely a dry recitation of facts; it is rich with anecdotes and personal judgments. Through Farington's pen, we gain insights into the personalities of major figures. He records interactions with, and comments on, a veritable who's who of the art establishment. This includes towering figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds (in the diary's early years, reflecting on his legacy), Benjamin West (Reynolds' successor as President of the Royal Academy), the brilliant portraitist Sir Thomas Lawrence, and the visionary poet and artist William Blake, whose eccentricities Farington noted.

A Man of Influence: The Royal Academy and Its Politics

Farington was not a passive observer; he was deeply enmeshed in the affairs of the Royal Academy. His diary reveals him to be a shrewd and influential figure, often acting as a kingmaker or power broker within the institution. He served on numerous committees and played a significant role in the Academy's internal politics, its elections, and the management of its exhibitions. His detailed accounts of Academy meetings, disputes, and decision-making processes are invaluable for understanding the functioning of this key institution during a formative period.

His influence extended to the careers of other artists. He was often consulted for advice, and his opinions carried weight. He could be a staunch ally or a formidable opponent. His diary entries reveal his efforts in organizing exhibitions, including those posthumously celebrating artists like Thomas Gainsborough, William Hogarth, and his own master, Richard Wilson, ensuring their legacies were appropriately honored. He was, in many ways, the unofficial historian and conscience of the Academy, deeply invested in its reputation and smooth operation. His conservative nature often led him to resist radical changes, but his dedication to the institution's stability was undeniable.

Interactions with Contemporaries: A Network of Artists

Farington's diary is a treasure trove of information about his interactions with a wide array of fellow artists, providing firsthand accounts of their work, personalities, and relationships.

His connection with J.M.W. Turner is particularly noteworthy. While Farington's own artistic style was more traditional, he recognized Turner's prodigious talent from an early age. The diary records Turner's activities, including his work at Dr. Thomas Monro's "academy" in Adelphi, where young artists like Turner and Thomas Girtin were employed to copy drawings. Farington documented Turner's rapid rise, his election to the Academy, and his sometimes controversial innovations. While not always uncritical, Farington's observations provide a contemporary perspective on one of Britain's greatest painters.

He also had dealings with John Constable, another giant of British landscape painting. Farington noted Constable's development and his struggles for recognition. He recorded, for instance, William Constable's (a different artist, a Yorkshire squire and amateur) work and Sir George Beaumont's influence on him. Sir George Beaumont, a prominent patron and amateur artist, was a significant figure in Farington's circle, and his opinions on art are frequently recorded.

Farington's diary mentions numerous other artists, painting a rich tapestry of the art scene. He writes of the irascible history painter James Barry, whose turbulent relationship with the Royal Academy eventually led to his expulsion. He notes the imaginative and often unsettling work of Henry Fuseli, another prominent RA known for his depictions of literary and mythological scenes. His collaboration with William Daniell on a book of Indian views in 1794 highlights his engagement with artists specializing in depicting foreign lands, a growing interest in the period.

The diary also records interactions with lesser-known figures, such as James Northcote, a former pupil of Reynolds and a painter of portraits and historical subjects. Farington even recounts an instance of an American merchant, also named James Northouls (likely a variant spelling or a different individual from the artist James Northcote), seeking his assistance in promoting his daughter's artistic endeavors. Such entries illustrate the breadth of Farington's social and professional network and the various roles he played within the art community. He also knew artists like Paul Sandby, another key figure in the development of British watercolour and topographical art.

Anecdotes and Observations: The Fabric of Daily Life

Beyond the high politics of the art world, Farington’s diary is filled with fascinating anecdotes that bring the period to life. He records conversations about medical matters, such as his interactions with the famous surgeon John Hunter, expressing concern over certain events in the medical community. His interest in current affairs is evident in his notes on significant public events, like the lengthy and sensational impeachment trial of Warren Hastings, the former Governor-General of Bengal.

These observations provide a rich context for the artistic developments of the time. They show that artists were not isolated figures but were deeply engaged with the broader social, political, and intellectual currents of their day. Farington’s meticulous recording of dinners, social calls, and studio visits paints a vivid picture of the daily life and concerns of a professional artist in Georgian London. He captured the anxieties about patronage, the rivalries between artists, the excitement of new discoveries, and the impact of national events on individual lives.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Joseph Farington's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he was a competent and respected practitioner of topographical landscape, contributing significantly to the visual record of Britain. His works, particularly the published views of the Lake District and the Thames, played a role in shaping public appreciation for British scenery and contributed to the burgeoning tourist trade in picturesque locations. His influence on the popularization of the Lake District, transforming it from a perceived wilderness to a desirable destination, is a notable aspect of his artistic impact.

However, it is his diary that constitutes his most profound and lasting contribution. It has become an indispensable resource for art historians, social historians, and literary scholars. The sheer volume of information, the range of topics covered, and the immediacy of his observations make it a historical document of immense value. It allows researchers to reconstruct the social networks of the art world, to trace the provenance of artworks, to understand the economics of the art market, and to gain insight into the critical debates of the period.

While his own artistic style might be viewed as somewhat conservative, especially when compared to the revolutionary changes being wrought by Turner and Constable towards the end of his life, Farington’s role as a chronicler, an institutional stalwart, and a facilitator within the art community was crucial. He was a man of his time, reflecting its tastes and its preoccupations, but through his diligent record-keeping, he transcended his era to provide future generations with an intimate and invaluable portrait of his world.

Exhibitions and Continued Study

The significance of Joseph Farington's work, both artistic and literary, continues to be recognized. His drawings and paintings are held in numerous public collections, including the Royal Academy itself, the British Museum, and the Yale Center for British Art.

Exhibitions have occasionally focused on his work. For example, The Wye Tour of Joseph Farington, 1803, would have showcased his sketches and diary entries related to his travels in that picturesque region, a popular tour for artists and writers. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has also featured his contributions, such as in virtual displays like At Nunnery in Cumberland, highlighting specific works and their context.

The most significant scholarly endeavor related to Farington is, of course, the publication of his diary. Edited by Kenneth Garlick, Angus Macintyre, and Kathryn Cave, and published by Yale University Press in sixteen volumes (plus an index volume), The Diary of Joseph Farington (1978-1984) made this extraordinary resource widely accessible to scholars. Its meticulous editing and comprehensive footnoting have greatly enhanced its utility for research. This publication has spurred countless studies and provided crucial evidence for numerous art historical arguments and biographies.

Conclusion: A Man of Art and Record

Joseph Farington was more than just a landscape painter; he was a central figure in the artistic life of his time. His paintings and drawings offer valuable depictions of Britain at a specific historical juncture, rendered with skill and precision. His active and influential role within the Royal Academy helped to shape that institution during a critical period of its development.

But it is through his diary that Farington speaks most clearly and enduringly to us. As a meticulous observer and recorder of his times, he left behind a legacy that extends far beyond his own canvases. He provided an intimate, detailed, and often candid account of the world of art in Georgian London, a world populated by some of the most iconic figures in British art history. For his diligence as a diarist, and for his contributions as an artist and Academician, Joseph Farington remains a figure of considerable importance, a key witness to a vibrant and transformative era in British art.