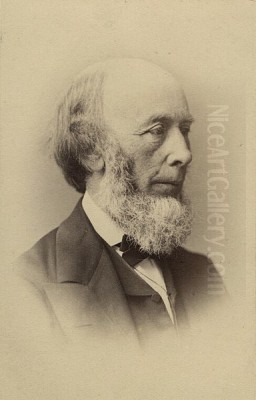

Richard Redgrave (1804-1888) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. His career was multifaceted, encompassing roles as a painter of genre scenes and landscapes, a dedicated and influential art administrator, a pioneering educator, and an art historian. His work reflected the social conscience of the Victorian era, and his efforts in art education and museum development left a lasting legacy on Britain's cultural institutions.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on April 30, 1804, in Pimlico, London, Richard Redgrave was the second son of William Redgrave. His early life was not one of artistic immersion; instead, he initially worked in his father's wire-fencing manufactory. This practical, industrial background perhaps subtly informed his later interest in design and its application. Despite the demands of the family business, Redgrave nurtured a passion for drawing and painting in his spare time. He would sketch from nature and visit galleries, developing his skills independently.

His formal artistic journey began in 1825 when he submitted a painting, "The River Brent, near Hanwell," to the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts. Its acceptance was a pivotal moment, leading to his enrollment as a student at the Royal Academy Schools. Here, he would have been exposed to the academic traditions of the time, studying antique sculpture and life drawing, and learning from established Academicians. The training at the Royal Academy was rigorous, emphasizing draughtsmanship and the grand manner, though Redgrave's own path would lead him more towards intimate genre scenes and landscapes.

By 1830, Redgrave made the decisive step to leave his father's company and dedicate himself fully to a career in art. This was a bold move, as the life of an artist was often precarious. He initially supported himself by teaching art, a role that would become a significant part of his life's work and profoundly shape his contributions to British art beyond his own canvases.

The Painter of Social Conscience

Redgrave's early artistic output included historical subjects, but he soon found his true voice in genre painting, particularly scenes depicting contemporary life and social issues. He became one of the first British artists to consistently address themes of poverty, hardship, and social injustice, predating the more famous social realist works of artists like Luke Fildes or Frank Holl.

His breakthrough painting in this vein was "Gulliver on the Farmer's Table" (1837), exhibited at the Royal Academy. While ostensibly an illustration of Swift's satire, it demonstrated his skill in narrative and detailed rendering. More pointedly social were works like "The Poor Teacher" (also known as "The Governess") of 1843, and a later version in 1844. These paintings poignantly depicted the plight of educated but impoverished women forced into the often thankless and isolating role of a governess, a common theme in Victorian literature and art, explored by writers like Charlotte Brontë and artists such as Rebecca Solomon.

"The Sempstress," painted in 1846, is perhaps his most iconic social commentary piece. Inspired by Thomas Hood's poem "The Song of the Shirt," it portrays a young woman, weary and alone, toiling late into the night with her needlework. The painting captured the public imagination, highlighting the exploitation of female laborers in the garment industry. Redgrave’s sympathetic portrayal, detailed observation of the meager surroundings, and the palpable exhaustion of the figure resonated deeply with Victorian audiences concerned about the "Condition of England."

Another significant work, "The Outcast" (1851), tackled the harsh Victorian morality surrounding illegitimate births and fallen women. It depicts a stern patriarch casting out his daughter and her child into a snowy, unforgiving night, while other family members react with varying degrees of grief and dismay. Such subjects were daring for their time and showcased Redgrave's commitment to using art as a vehicle for social reflection. These works placed him in a similar thematic territory to Augustus Egg, whose triptych "Past and Present" (1858) also dealt with the consequences of female transgression.

Landscapes and Literary Themes

While known for his social realism, Redgrave was also an accomplished landscape painter. His early work, "The River Brent, near Hanwell," indicated this interest. Throughout his career, he continued to paint landscapes, often imbued with a gentle, observant quality. These were typically English scenes, rendered with attention to natural detail and atmospheric effects, perhaps showing a quieter affinity with the tradition of John Constable, though without Constable's revolutionary brushwork.

He also explored literary and historical themes. "Ophelia Weaving Her Garlands" (1842) is a notable example, depicting the tragic heroine from Shakespeare's Hamlet. This subject was popular among Victorian artists, including John Everett Millais, whose later Pre-Raphaelite version is now iconic. Redgrave’s interpretation is more in keeping with the romantic sensibilities of the earlier part of the century. "The Return of Olivia to Her Parents" (1839, based on Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield, and sometimes referred to as "Olivia's Return to Her Parents," 1845 for a later version or similar subject) was another popular literary subject he tackled, demonstrating his ability to convey narrative and emotion within a carefully constructed composition. "Country Cousins" (1848) was a charming genre scene that, while not overtly a social critique, subtly explored social nuances and rural life.

"The Emigrant's Last Sight of Home" (1858) combined his interest in landscape with a poignant social narrative. It depicted a family on a ship, looking back at the receding coastline of England, a theme that resonated with the widespread emigration occurring during the Victorian era due to economic hardship or the lure of new opportunities in the colonies. Ford Madox Brown's "The Last of England" (1855) is a more famous treatment of a similar theme, but Redgrave's version also captures the sorrow and uncertainty of departure.

A Pioneer in Art Education

Richard Redgrave's contributions to art education were arguably as significant, if not more so, than his achievements as a painter. He was deeply involved in the movement to reform art and design training in Britain, which gained momentum following concerns about the quality of British industrial design compared to its European rivals, particularly highlighted by the Great Exhibition of 1851.

His formal involvement began in 1847 when he was appointed a botanical lecturer at the Government School of Design, located at Somerset House (this institution would later evolve into the Royal College of Art). His understanding of plant morphology was considered valuable for designers. He quickly rose through the ranks, becoming Headmaster in 1848 and then Art Superintendent in 1852. In this capacity, he worked closely with Henry Cole, a key figure in Victorian design reform and the driving force behind the Great Exhibition and the South Kensington Museum.

Redgrave played a crucial role in developing a national system of art education. In 1857, he was appointed the first Inspector-General for Art at the newly formed Science and Art Department, based in South Kensington. He was instrumental in devising a national curriculum for art instruction, which was implemented in a network of art schools across the country. This curriculum emphasized systematic instruction in drawing, geometry, and perspective, aiming to provide a solid foundation for both fine artists and industrial designers. His approach, while structured, aimed to foster an appreciation for principles of design derived from nature, a philosophy shared by contemporaries like Owen Jones and Christopher Dresser.

He co-authored, with his brother Samuel Redgrave, "A Manual of Design" (1876), which codified many of his teaching principles. His influence shaped art education in Britain for decades, promoting a more systematic and accessible approach to art training. He believed strongly in the social utility of art and design, and his educational work aimed to raise the standard of British manufacturing and improve public taste.

The South Kensington Museum and Public Service

Redgrave's administrative talents extended to the burgeoning museum world. He was intimately involved with the establishment and early development of the South Kensington Museum, the precursor to the Victoria and Albert Museum. Following the success of the Great Exhibition of 1851, funds were available to create institutions dedicated to art and science. Redgrave was appointed Keeper of Paintings at the South Kensington Museum.

He was responsible for organizing and cataloging the collections, including the Sheepshanks collection of British art, which formed a core part of the museum's early holdings. His work helped to establish the museum as a major center for the study and display of art and design. He was also involved in organizing exhibitions, including a significant retrospective of the works of William Mulready in 1864, and another of his own works.

His public service was recognized internationally. For his role as executive chairman for the British art section at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855, he was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honour by the French government. This demonstrated his standing not only as an artist but as a capable organizer and representative of British art on the international stage. In 1869, he was offered a knighthood for his services to art, an honor he declined, a decision that speaks to a certain modesty or perhaps a desire to remain focused on his work without the trappings of such titles.

He was an active member of the Royal Academy, having been elected an Associate (ARA) in 1840 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1851. He exhibited regularly at the Academy's annual exhibitions for over fifty years. He also participated in other artistic groups, being a founding member of the Etching Club, which aimed to promote the art of etching in Britain. Other members of the Etching Club included artists like Charles West Cope and Thomas Creswick.

Artistic Collaborations and Writings

Beyond his official duties, Redgrave contributed to art scholarship. His most notable literary work was "A Century of Painters of the English School," published in 1866 and co-authored with his elder brother, Samuel Redgrave (1802-1876), who was a civil servant and also compiled biographical dictionaries of artists. This two-volume work was a comprehensive survey of British art from the time of William Hogarth to their own period. It remains a valuable historical resource, offering insights into how Victorian critics and artists viewed their artistic predecessors and contemporaries. It discussed a wide array of artists, from giants like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough to lesser-known figures.

His collaboration with Henry Cole in the Department of Science and Art was particularly significant. Cole was a dynamic and sometimes controversial figure, but his partnership with Redgrave was productive. Together, they shaped the direction of government-sponsored art education and the development of the South Kensington complex. While Cole was often the public face and driving force, Redgrave provided the artistic expertise and pedagogical framework.

Later Years and Legacy

Richard Redgrave continued to paint and remained active in his administrative roles for many years. He retired from his position as Inspector-General for Art and Director of the Art Division at South Kensington in 1875, and from his role as Surveyor of The Queen's Pictures in 1880, a post he had held since 1857, which involved caring for the Royal Collection. His eyesight began to fail in his later years, which curtailed his painting activities.

He died on December 14, 1888, at his home at 27 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington, London, at the age of 84. He was buried in Brompton Cemetery.

Richard Redgrave's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he was a significant figure in the development of Victorian social realism, using his art to draw attention to the plight of the marginalized and to comment on contemporary social issues. Works like "The Sempstress" and "The Outcast" remain powerful examples of this genre. His landscapes, though less celebrated, demonstrate a consistent and sensitive engagement with the British countryside.

However, his most enduring impact may lie in his work as an educator and administrator. His reforms in art education, the national curriculum he helped to establish, and his role in the formation and early management of the South Kensington Museum had a profound and lasting effect on the British art world. He helped to professionalize art teaching and make art education more widely accessible. The institutions he helped to build, notably the Royal College of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum, continue to be world-leading centers for art and design.

Redgrave and His Contemporaries

Richard Redgrave operated within a vibrant and diverse Victorian art world. His social realist paintings can be seen alongside the work of artists like Augustus Egg, whose narrative paintings often explored moral dilemmas, and later figures such as Luke Fildes ("Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward") and Frank Holl ("Newgate: Committed for Trial"), who brought an even grittier realism to their depictions of poverty and social institutions.

While his style differed significantly from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (founded in 1848 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt), he was a contemporary of this influential movement. The Pre-Raphaelites, with their emphasis on truth to nature, bright colors, and complex symbolism, offered a radical alternative to academic art. Redgrave, while also valuing observation, remained more aligned with established academic practices in his technique, though his subject matter was often innovative.

In the realm of landscape, he worked in a period that had seen the towering achievements of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable. While Redgrave did not aim for their sublime or revolutionary approaches, his quieter, more pastoral landscapes found an appreciative audience. He was a contemporary of other landscape painters like Clarkson Stanfield and David Roberts, known for their topographical and sometimes exotic scenes.

His administrative and educational work brought him into contact with a wide range of artists and public figures. His collaboration with Sir Henry Cole was central to many of his achievements in this sphere. As a Royal Academician, he would have known most of the leading artists of the day, from the President Sir Charles Eastlake to popular painters like William Powell Frith, famous for his panoramic scenes of modern life such as "Derby Day."

His writings, particularly "A Century of Painters," show his engagement with the history of British art and his assessments of figures like Sir Thomas Lawrence, Sir David Wilkie, and Benjamin Robert Haydon. This historical perspective informed his own practice and his approach to art education.

Critical Reception and Historical Standing

During his lifetime, Richard Redgrave enjoyed considerable success and respect. His paintings were regularly exhibited and often well-received, particularly those that tapped into the Victorian appetite for narrative and sentiment. His administrative achievements were widely recognized, even if the bureaucratic nature of such work sometimes overshadowed his artistic output in public perception.

In the decades following his death, like many Victorian artists, Redgrave's reputation experienced a period of decline as new artistic movements such as Impressionism and Modernism came to dominate critical discourse. Victorian art, with its emphasis on narrative, detail, and moral sentiment, was often dismissed as sentimental or overly academic.

However, from the mid-20th century onwards, there has been a significant reassessment of Victorian art. Art historians have recognized the complexity, innovation, and social relevance of the period's artistic production. Within this revival, Richard Redgrave's contributions have been re-evaluated. Scholars now acknowledge his importance as a pioneer of social realism in British art and his crucial role in the development of art education and museum institutions. His paintings are valued not only for their technical skill and aesthetic qualities but also as important historical documents that provide insights into the social concerns and cultural values of the Victorian era.

Richard Redgrave may not have achieved the posthumous fame of some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, but his dedicated work across multiple fields left an indelible mark on British art and culture. He was a man of his time, deeply engaged with the issues and opportunities of the Victorian age, and his legacy endures in the institutions he helped to shape and the art he created.