Joseph Mallord William Turner stands as a colossus in the annals of art history, particularly within the British tradition. Born in the heart of London in 1775, during a period of burgeoning industrial change and evolving artistic sensibilities, Turner would rise from humble beginnings to become arguably the most innovative and influential landscape painter of the Romantic era. His life spanned a period of immense transformation, and his art not only reflected these changes but often anticipated future movements, earning him the enduring moniker "the painter of light." His exploration of colour, atmosphere, and the raw power of nature redefined the possibilities of landscape painting and left an indelible mark on generations of artists to come.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

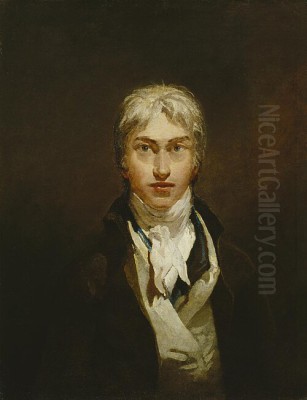

Joseph Mallord William Turner entered the world on April 23, 1775, in Covent Garden, London. His father, William Turner, was a barber and wig-maker, a modest trade that placed the family within the lower-middle class of the bustling metropolis. His mother, Mary Marshall, tragically suffered from mental instability, a condition that worsened over time, leading to her eventual admission to Bethlem Hospital, an asylum, in 1800, where she remained until her death. This difficult family background perhaps contributed to the young Turner's introspective nature and his deep immersion in his burgeoning artistic talents.

From a remarkably early age, Turner displayed an undeniable aptitude for drawing and painting. His father recognized his son's gift, proudly exhibiting the boy's drawings in his shop window, even selling them for small sums. This early encouragement was crucial. Recognizing the need for formal training, Turner was enrolled at the Royal Academy of Arts schools in 1789, at the exceptionally young age of just fourteen. He quickly absorbed the lessons offered, studying perspective and the works of Old Masters, while also working for architects and engravers, honing his skills in draughtsmanship and topographical accuracy. Just a year later, in 1790, the fifteen-year-old Turner saw his first watercolor accepted for the prestigious Royal Academy summer exhibition, marking the public debut of a prodigious talent.

The Path to Mastery: Watercolors and Oils

Turner's early career was significantly rooted in the medium of watercolor. He traveled extensively throughout England and Wales during the 1790s, fulfilling commissions for topographical views and architectural studies. These journeys allowed him to meticulously observe the effects of light and weather on the landscape, skills that would become central to his later, more dramatic works. His watercolors from this period, while often precise, already hinted at a growing interest in atmospheric effects and a departure from purely descriptive representation. He rapidly gained a reputation for his technical brilliance and his ability to capture the nuances of the British landscape.

The turn of the century marked a significant evolution in Turner's practice. While he never abandoned watercolor, he increasingly turned his attention to oil painting, seeking a medium capable of conveying greater depth, intensity, and emotional weight. His ambition grew, moving beyond topography towards historical landscapes and dramatic marine subjects. A pivotal moment came in 1802 when, at the age of only 27, he was elected a full member of the Royal Academy (RA), a remarkable achievement confirming his status within the British art establishment. This period saw him engage directly with the tradition of classical landscape painting, particularly the works of the 17th-century master Claude Lorrain, whose idealized compositions and handling of light Turner both admired and sought to rival, and sometimes surpass, in works like Dido Building Carthage. He also absorbed lessons from Dutch marine painters like Willem van de Velde the Younger.

Travels and the Sketchbook Habit

Travel was fundamental to Turner's artistic process throughout his life. His early tours within Britain were soon followed by more ambitious journeys across continental Europe, made possible initially by the brief Peace of Amiens in 1802 and continued extensively after the Napoleonic Wars. He visited France, Switzerland, Italy (most notably Venice, Rome, and Naples), Germany, and the Low Countries. These trips were not leisurely holidays but intensive periods of observation and sketching. Turner was an indefatigable sketcher, filling notebook after notebook with rapid pencil drawings, watercolor studies, and written notes capturing fleeting effects of light, cloud formations, architectural details, and the raw energy of nature.

It is estimated that Turner left behind over 300 sketchbooks and around 30,000 works on paper upon his death. These sketches formed an immense visual library, a repository of motifs and atmospheric observations that he would draw upon back in his London studio, often years later, to compose his finished oil paintings and watercolors. Unlike his contemporary John Constable, who often painted large-scale sketches directly from nature, Turner primarily used his sketches as reference material, transforming his on-the-spot impressions into highly imaginative and often dramatically heightened compositions in the studio. His travels provided the raw material for his visionary interpretations of the natural and man-made world.

The Romantic Vision: Nature, Light, and the Sublime

Turner's art is intrinsically linked to the Romantic movement, which emphasized emotion, individualism, and the awe-inspiring power of nature. He was less interested in merely recording the appearance of a landscape and more concerned with conveying the feelings it evoked – a concept central to the theory of the Sublime, which explored experiences of awe, terror, and grandeur in the face of nature's vastness. Turner excelled at depicting the most dramatic and transient aspects of the natural world: tumultuous storms at sea, blinding snowstorms, fiery sunsets, and ethereal mists. In his paintings, nature is often portrayed as an overwhelming force, dwarfing human figures and endeavors.

Light was Turner's primary tool for achieving these effects. He studied its properties relentlessly, exploring how it could dissolve form, create atmosphere, and evoke powerful emotions. His use of color became increasingly bold and experimental, moving away from traditional tonal harmonies towards vibrant, often non-naturalistic hues that conveyed the intensity of his vision. He wasn't simply painting light; he was painting with light, making it the true subject of many of his works. This focus distinguished him from earlier landscape painters like Thomas Gainsborough or Richard Wilson, pushing the boundaries of representation towards a more subjective and expressive interpretation of the world.

Masterworks of the Middle Period

During the first few decades of the 19th century, Turner produced a series of major oil paintings that cemented his reputation while also showcasing his evolving style. Calais Pier (exhibited 1803), based on his first trip abroad, is a dynamic portrayal of rough seas and human activity, demonstrating his mastery of marine painting and his ability to capture energy and movement. His historical landscapes, such as Dido Building Carthage, or The Rise of the Carthaginian Empire (exhibited 1815), were ambitious attempts to elevate landscape painting to the level of history painting, directly challenging the legacy of Claude Lorrain. Turner famously stipulated in his will that this painting should hang alongside one of Claude's masterpieces in the National Gallery.

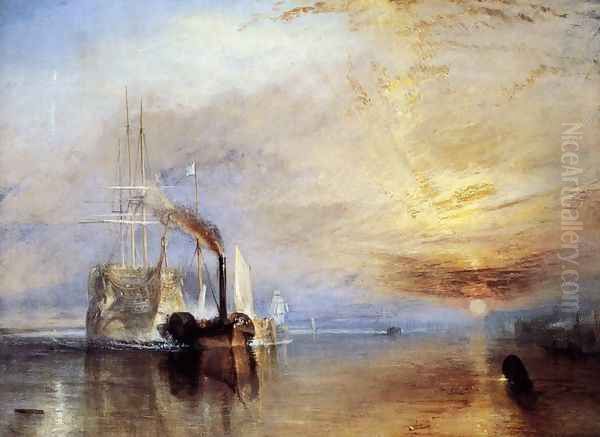

One of his most beloved and poignant works is The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last Berth to be broken up, 1838 (exhibited 1839). This painting depicts the majestic old warship, a veteran of the Battle of Trafalgar, being towed by a small, dark, modern steam tug to be dismantled. The juxtaposition of the ghostly, beautiful sailing ship bathed in the light of a dramatic sunset and the functional, smoke-belching tugboat serves as a powerful elegy for a passing era and a commentary on the advent of the industrial age. The painting resonates with nostalgia and a sense of sublime beauty in decay, showcasing Turner's ability to imbue landscape with deep symbolic meaning.

Innovation and Controversy: The Later Style

In the later stages of his career, particularly from the 1830s onwards, Turner's style became increasingly radical and experimental, often baffling critics and the public. Forms began to dissolve into swirling vortexes of light and color, and the distinction between sea, sky, and land often blurred into near abstraction. He pushed the expressive potential of paint itself, applying it in thick impastos, scumbling layers, and using glazes to achieve unprecedented luminosity and atmospheric depth. His focus shifted almost entirely to capturing the elemental forces of nature and the ephemeral effects of light.

Works like Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth (exhibited 1842) exemplify this late style. The painting is a maelstrom of churning waves, snow, and smoke, with the steamboat barely discernible at its heart. Legend has it, possibly encouraged by Turner himself, that he had himself lashed to the mast of a ship during a storm for four hours to experience its full fury. Whether true or not, the anecdote reflects the painting's immersive and visceral quality. Critics were often hostile, one famously describing it as "soapsuds and whitewash." Yet, these works were revolutionary, anticipating the concerns of Impressionism and even Abstract Expressionism in their emphasis on subjective experience and the materiality of paint. Another key work from this period, Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway (exhibited 1844), dramatically captures the energy and novelty of modern technology hurtling through a rain-swept landscape, merging nature and industry in a dynamic, atmospheric vision.

Venice and the Allure of Atmosphere

Venice held a special fascination for Turner, and he visited the city multiple times, beginning in 1819. The unique interplay of light, water, and architecture provided him with endless inspiration. His Venetian paintings, primarily watercolors but also several significant oils, are among his most celebrated works. He moved away from the precise topographical views favoured by earlier artists like Canaletto and Francesco Guardi, instead focusing on capturing the city's ethereal atmosphere, its shimmering reflections, and the dramatic effects of sunrise, sunset, and moonlight on its lagoons and canals.

In paintings like The Grand Canal, Venice (various versions) or Venice: The Dogana and San Giorgio Maggiore (exhibited 1834), solid forms seem to melt into the luminous haze. Palaces and churches become silhouettes against glowing skies, their reflections dancing on the water's surface. Turner used color with extraordinary freedom, employing brilliant yellows, oranges, reds, and blues to convey the magical quality of Venetian light. These works are less about the specific details of the city and more about evoking its mood and sensory experience, showcasing his mastery of light and atmosphere at its peak. His Venetian scenes deeply impressed later artists, including Claude Monet, who would also travel to Venice to capture its unique light.

Thematic Concerns: History, Modernity, and the Sea

While renowned as a landscape painter, Turner's thematic range was remarkably broad. He tackled historical subjects, often drawn from classical antiquity or the Bible, such as The Tenth Plague of Egypt (exhibited 1802) or The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire (exhibited 1817). He also engaged with mythological themes and scenes inspired by literature, particularly the poetry of Byron and Scott. His work often carried complex allegorical or symbolic meanings, reflecting on themes of empire, mortality, the power of nature, and the impact of human history.

The sea was a recurring and vital theme throughout his career. From early depictions of fishing boats and ports to later, more tumultuous scenes of shipwrecks and storms, Turner captured the ocean's beauty, power, and danger like few artists before him. The Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon coming on) (exhibited 1840) is one of his most powerful and disturbing works, combining a sublime depiction of a stormy sea and fiery sunset with a horrific contemporary event – the Zong massacre, where enslaved people were thrown overboard for insurance purposes. The painting is a searing indictment of inhumanity set against the backdrop of nature's terrifying indifference. Furthermore, as seen in Rain, Steam and Speed and The Fighting Temeraire, Turner did not shy away from depicting the modern world, engaging with the transformative impact of the Industrial Revolution on both the landscape and society.

Personal Life: Relationships and Reclusion

Turner's personal life remained largely private and somewhat unconventional for his time. He never married, but he had significant relationships with two women. Early in his career, he formed a connection with Sarah Danby, the widow of a musician. While the exact nature of their relationship is debated, it is widely believed she was his mistress and bore him two daughters, Eveline (possibly born around 1801) and Georgiana (born 1811). Although he did not live with them openly, he acknowledged and provided support for his daughters.

Later in life, particularly after the death of his father in 1829, Turner formed a close and lasting relationship with Sophia Caroline Booth. She was a widowed landlady from Margate, a seaside town Turner frequently visited. From the mid-1840s until his death, Turner lived with Mrs. Booth in Chelsea, using her name as an alias (sometimes going by "Mr. Booth" or even "Admiral Booth") to maintain his privacy. His father, William Turner senior, had lived with him for thirty years, acting as his studio assistant, general helper, and close companion. His father's death deeply affected Turner, plunging him into periods of depression and likely contributing to his increasing withdrawal from society.

As he aged, Turner became known for his eccentricities and reclusive nature. He grew more solitary, avoiding social gatherings and even Royal Academy functions. He was notoriously secretive about his painting techniques and often gruff or taciturn in his interactions. Despite his fame, he lived relatively modestly and became increasingly reluctant to sell his later works, perhaps feeling they were misunderstood or wanting to keep his artistic legacy intact for the nation.

Critical Reception and Support

Throughout his long career, Turner's work consistently provoked strong reactions, ranging from adulation to outright hostility. His early successes earned him academic honours and patronage, but his increasingly bold experiments with light and color often met with incomprehension and ridicule from conservative critics. They accused him of lacking finish, distorting reality, and indulging in wild extravagance. The infamous description of Snow Storm as "soapsuds and whitewash" is indicative of the bewilderment his late style could inspire. Even fellow artists, like John Constable, while acknowledging his genius, sometimes found his work perplexing.

However, Turner also had powerful champions. His most significant advocate was the influential critic and writer John Ruskin. Starting with the publication of the first volume of Modern Painters in 1843, Ruskin passionately defended Turner against his detractors, arguing that Turner's depiction of nature was more truthful and profound than that of the Old Masters. Ruskin's eloquent and detailed analyses helped shape public understanding and appreciation of Turner's work, particularly his later, more challenging paintings. Ruskin celebrated Turner's ability to capture the dynamism, infinity, and sublime power of the natural world. Other supporters included patrons like Walter Fawkes and the 3rd Earl of Egremont, who commissioned works and provided spaces for Turner to paint. Figures within the Academy, such as its president Benjamin West during Turner's early rise, recognized his immense talent even amidst controversy.

Legacy and Influence: Shaping Future Art

Joseph Mallord William Turner died on December 19, 1851, in the modest house he shared with Sophia Booth in Chelsea. In his will, he bequeathed the vast majority of his finished paintings and thousands of sketches and watercolors to the British nation, with the intention that a dedicated gallery be built to house them. This extraordinary gift, known as the Turner Bequest, now forms the core of the collection at Tate Britain and remains one of the most comprehensive archives of a single artist's work anywhere in the world.

Turner's influence on the course of Western art has been profound and enduring. His revolutionary treatment of light and color, his emphasis on atmospheric effects, and his increasingly abstract handling of form directly paved the way for French Impressionism. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, who saw Turner's work while visiting London in the 1870s, were deeply impressed by his freedom and his ability to capture fleeting moments. His expressive brushwork and subjective vision also resonated with later movements, including Post-Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism; the atmospheric color fields of Mark Rothko, for instance, echo Turner's late, light-filled canvases.

Beyond painting, Turner's legacy continues to be felt. The prestigious Turner Prize, awarded annually to a contemporary British artist, was named in his honour, acknowledging his role as a radical and transformative figure in art. His life and work continue to inspire artists, writers, and filmmakers, cementing his status not just as a master of landscape, but as a visionary who fundamentally changed the way we see and represent the world. His work remains a testament to the power of nature, the expressive potential of paint, and the enduring quest to capture the elusive quality of light itself.

Conclusion: Turner's Enduring Significance

J.M.W. Turner remains a towering figure in art history, a painter whose genius lay in his ability to harness the raw elements of nature – light, water, air – and transform them into paintings of astonishing emotional power and visual complexity. From his early topographical watercolors to his late, near-abstract visions, his career was one of relentless innovation and exploration. He pushed the boundaries of landscape painting, imbuing it with the drama of history painting and the intensity of personal feeling. His mastery of light and color, his engagement with the sublime forces of nature, and his prescient anticipation of modern art movements secure his place as one of the most important and influential artists Britain has ever produced. The "painter of light" continues to illuminate the world of art, his canvases vibrant portals into the awesome beauty and terrifying power of the world around us.