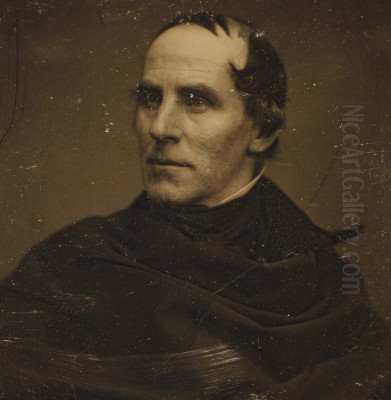

Thomas Cole stands as a pivotal figure in the annals of American art history. An immigrant who embraced the untamed beauty of his adopted homeland, he translated the grandeur and moral weight of the American wilderness onto canvas, effectively founding the nation's first significant art movement, the Hudson River School. His work, deeply rooted in Romanticism yet uniquely American, explored the complex relationship between nature, civilization, and the divine, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural identity of the United States. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of a painter who not only captured landscapes but also shaped how a nation perceived itself.

Early Life and Transatlantic Journey

Thomas Cole's story begins not in the American wilderness he would come to immortalize, but in the industrial heartland of England. Born on February 1, 1801, in Bolton-le-Moors, Lancashire, his early years were set against the backdrop of the burgeoning Industrial Revolution, an experience that likely fostered his later ambivalence towards unchecked progress. His family, facing economic hardship, made the life-altering decision to emigrate to the United States in 1818.

The transatlantic voyage itself was a formative experience for the seventeen-year-old Cole. He witnessed the vastness of the ocean, the power of storms, and the brilliance of the untainted night sky. These encounters with the raw elements of nature ignited a profound fascination that would fuel his artistic vision. The journey instilled in him a sense of wonder and perhaps an early interest in the geological forces shaping the landscapes he would later paint.

Upon arrival, the Cole family initially settled in Philadelphia before moving westward to Steubenville, Ohio. This period was marked by struggle and adaptation to a new world. It was in these early years in America that Cole began to seriously pursue art, initially finding modest work that hinted at his burgeoning talent.

Artistic Beginnings and the Shift to Landscape

Cole's formal artistic training was somewhat itinerant. In Philadelphia, around 1823-1824, he received some instruction, notably studying briefly under a portrait painter named Stein. Like many aspiring artists of the time, he initially focused on portraiture, a more commercially viable genre. He worked as an itinerant portrait painter in Ohio and Pennsylvania, honing his technical skills but likely finding the work creatively unfulfilling.

His true passion lay elsewhere. Inspired by the dramatic landscapes of the American continent, which stood in stark contrast to the tamed countryside of England and the industrial scenes of his youth, Cole felt an irresistible pull towards landscape painting. Engravings of European landscapes provided early inspiration, but it was the direct encounter with the American environment that truly shaped his destiny.

A pivotal moment came with his move back east, eventually settling in New York City in 1825. This relocation placed him closer to the burgeoning art scene and, crucially, nearer to the landscapes that would define his career – the Hudson River Valley and the Catskill Mountains. It marked a definitive shift away from portraiture towards the genre where he would make his most significant contributions.

Discovering the American Wilderness: The Catskills

The year 1825 proved transformative. Cole embarked on a sketching trip up the Hudson River, venturing into the Catskill Mountains. This region, with its dramatic peaks, deep forests, cascading waterfalls, and expansive views, captivated him. He saw in this wilderness not just physical beauty, but a reflection of divine creation, a place where one could commune with nature and contemplate higher truths.

Returning to New York City with sketches filled with the raw energy of the Catskills, Cole produced several landscape paintings. Three of these works were purchased by prominent figures in the city's art establishment: the respected historical painter Colonel John Trumbull, the influential artist and writer William Dunlap, and the notable collector Asher B. Durand, who would himself become a leading landscape painter and Cole's close friend.

Trumbull's recognition was particularly significant. Impressed by Cole's talent, he reportedly sought out the young artist, purchased one of his paintings, and connected him with influential patrons, including Daniel Wadsworth of Hartford, Connecticut, and Luman Reed, a New York merchant. This early success and patronage provided Cole with crucial support and visibility, effectively launching his career as a landscape painter. His Catskill paintings struck a chord, resonating with a growing national interest in the unique character of the American landscape.

The Birth of the Hudson River School

Cole's success and his distinctive approach to landscape painting laid the groundwork for what would become known as the Hudson River School. Though not a formal institution, the term describes a group of mid-19th-century American painters inspired by Cole's vision. They shared a belief in the spiritual and aesthetic significance of the American landscape, particularly the Hudson River Valley, the Catskills, the Adirondacks, and the White Mountains of New Hampshire.

As the movement's progenitor, Cole established its core tenets. His work combined detailed observation of nature, often based on meticulous sketches made outdoors, with a Romantic sensibility that emphasized emotion, awe, and the sublime power of the wilderness. He saw landscape painting not merely as topographical representation but as a vehicle for conveying moral, religious, and philosophical ideas.

The artists who followed Cole, including Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church (Cole's only formal pupil), Sanford Robinson Gifford, Jasper Francis Cropsey, and John Frederick Kensett, expanded upon his themes and techniques. While their individual styles varied, they were united by a reverence for nature and a desire to capture the unique character of the American continent. Cole's pioneering efforts provided the inspiration and the artistic language for this first truly indigenous American school of painting.

European Sojourns and Artistic Evolution

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons and study the works of the Old Masters, Cole embarked on his first extended trip to Europe in 1829, funded in part by his patron Luman Reed. He spent several years abroad, primarily in England, France, and Italy, returning to the United States in 1832. This period was crucial for his artistic development and philosophical outlook.

In London, Cole admired the works of British landscape painters like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, whose atmospheric effects and dramatic compositions resonated with his own sensibilities. However, he also found himself critical of what he perceived as an over-cultivation of the European landscape compared to the wildness of America. In Paris, he studied at the Louvre, expressing particular admiration for the idealized landscapes of the 17th-century French master Claude Lorrain, whose compositional structures and handling of light would influence Cole's more allegorical works.

Italy, particularly Rome and its surrounding countryside (the Campagna), had a profound impact. The ruins of ancient civilizations scattered amidst the landscape sparked Cole's imagination, leading him to contemplate the rise and fall of empires – a theme that would dominate some of his most ambitious works. It was also during his time abroad, particularly in Italy, that Cole experienced a deepening of his religious faith, becoming a devout Episcopalian. This spiritual awakening would increasingly inform the moral and allegorical dimensions of his art.

Masterworks: Allegory and Landscape

Upon his return to America, Cole entered his most productive and ambitious period, creating the large-scale allegorical series and iconic landscapes for which he is best known. These works cemented his reputation and showcased his unique blend of detailed naturalism and profound thematic content.

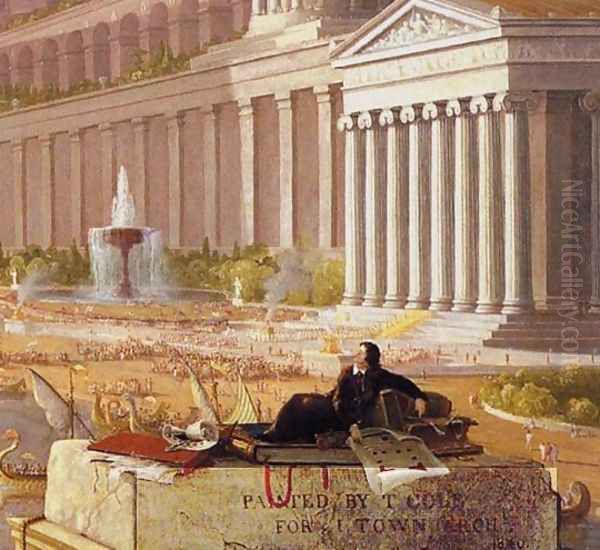

The Course of Empire (1833-1836): Commissioned by Luman Reed, this monumental series of five paintings traces the cyclical history of an imaginary civilization, from a savage state of nature, through pastoral arcadia, glorious consummation, violent destruction, and finally, desolate ruin. Set in the same identifiable landscape under different conditions, the series serves as a cautionary tale about the transience of human ambition and the potential consequences of unchecked expansion and societal decay, reflecting anxieties prevalent in Jacksonian America. It remains one of the most powerful allegorical statements in American art.

The Voyage of Life (1840, repeated 1842): Perhaps Cole's most beloved work, this series of four paintings – Childhood, Youth, Manhood, and Old Age – depicts an allegorical journey down the River of Life. Each canvas represents a stage of human existence, guided by a guardian angel, navigating changing landscapes that mirror the emotional and spiritual challenges of life. From the innocent emergence from a cave in Childhood to the hopeful ascent towards heavenly light in Old Age, the series offers a deeply personal and universally resonant meditation on faith, mortality, and the human condition. Cole painted two versions; the first is housed at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York, and the second, slightly larger set, resides at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (1836): This iconic painting is often considered Cole's masterpiece of pure landscape, yet it is rich with underlying meaning. It presents a panoramic view of the Connecticut River Valley, dramatically divided into two halves. On the left, a wild, stormy wilderness represents untamed nature. On the right, sunlit, cultivated fields symbolize settlement and civilization. Cole includes a tiny self-portrait in the foreground, nestled in the wilderness but looking out towards the viewer, seemingly asking them to contemplate the relationship between these two realms and the future direction of the American landscape. The Oxbow masterfully combines topographical accuracy with Romantic drama and subtle commentary.

Other Notable Works: Cole produced numerous other significant paintings. The Titan's Goblet (1833) is an enigmatic fantasy landscape featuring a colossal stone cup holding a miniature world, evoking themes of nature's grandeur and mystery. The Architect's Dream (1840) contrasts various historical architectural styles, reflecting Cole's interest in history and the built environment. His numerous views of the Catskills, such as Kaaterskill Falls and Sunset in the Catskills, celebrate the specific beauty of the region that first inspired him. Works like The Past and The Present (1838), now at the Mead Art Museum, further explore historical themes through paired landscapes.

Themes and Philosophy: Nature, Civilization, and Faith

Cole's art is interwoven with recurring themes that reflect his deeply held beliefs and his observations of the changing American scene. Central to his work is the tension between the pristine beauty of the wilderness and the encroaching forces of civilization and industrialization.

He revered nature as a manifestation of God's creation, a source of spiritual renewal, and a repository of moral lessons. His landscapes often evoke feelings of awe and the sublime, emphasizing the power and grandeur of the natural world in contrast to human insignificance. This reverence, however, was tinged with anxiety. Cole witnessed firsthand the rapid expansion of settlement, the clearing of forests for agriculture, and the beginnings of industrial development along America's rivers.

In essays like his "Essay on American Scenery" (1836), and implicitly in paintings like The Oxbow and The Course of Empire, Cole expressed concern about the destructive potential of human progress. He lamented the loss of wilderness and advocated for its preservation, not just for its aesthetic beauty but for its spiritual and national value. In this sense, Cole can be seen as an early voice in the American conservation movement, using his art to foster an appreciation for the natural environment and to question the relentless pursuit of material wealth at nature's expense.

His religious faith provided a framework for interpreting both nature and history. The allegorical series, in particular, are imbued with Christian symbolism, exploring themes of temptation, redemption, mortality, and divine providence. For Cole, landscape painting was not merely descriptive; it was a moral art form capable of elevating the viewer's thoughts and spirit.

Mentorship and Influence: Shaping the Next Generation

Thomas Cole's impact extended beyond his own canvases; he played a crucial role in nurturing the next generation of American landscape painters. His most direct influence was on Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), who studied with Cole in Catskill, New York, from 1844 to 1846. Church absorbed Cole's technical methods, his emphasis on detailed preliminary sketches, and his passion for dramatic natural effects. While Church developed his own distinct style, characterized by panoramic vistas and scientific detail (influenced by thinkers like Alexander von Humboldt), his foundational training with Cole was paramount. Church went on to become one of the most celebrated painters of the second generation of the Hudson River School.

Cole's friendship and artistic dialogue with Asher B. Durand (1796-1886) were also significant. Although Durand was slightly older and already established as an engraver and portraitist, Cole's success inspired him to turn fully to landscape painting. Durand shared Cole's reverence for nature but adopted a more naturalistic style, emphasizing direct, detailed observation over allegory. His famous essay "Letters on Landscape Painting" (1855) advocated for painting directly from nature, complementing Cole's more Romantic and allegorical approach. Together, Cole and Durand represent the foundational pillars of the Hudson River School.

Cole's influence permeated the wider artistic community. His success demonstrated the viability of landscape painting as a serious artistic pursuit in America. Artists like Sanford Robinson Gifford, Jasper Francis Cropsey, John Frederick Kensett, and even later figures associated with Luminism or Western exploration like Albert Bierstadt, operated within the tradition Cole had largely established, even as they forged their own paths. His work set a standard and provided a point of departure for subsequent American landscape art.

Connections and Community: The New York Art World

Cole was an active participant in the burgeoning art community of New York City. He was a founding member of the National Academy of Design in 1825, alongside other prominent artists like Samuel F. B. Morse, Asher B. Durand, and John Trumbull (though Trumbull was associated with the older American Academy of Fine Arts, relations were complex). The National Academy provided crucial exhibition opportunities for artists and helped professionalize the art world in America. Cole regularly exhibited his works there, gaining critical attention and patronage.

His relationships with patrons were vital. Luman Reed, who commissioned The Course of Empire, was not just a buyer but a supportive friend who shared Cole's intellectual interests. Daniel Wadsworth, an amateur artist and architect from Hartford, was another key early supporter who commissioned works and facilitated Cole's European travels. These relationships highlight the importance of enlightened patronage in enabling ambitious artistic projects in 19th-century America.

Cole also engaged with the broader cultural milieu, associating with writers like William Cullen Bryant, whose poetry often shared Cole's Romantic sensibility towards nature. He participated in discussions about art, nature, and national identity, contributing to the intellectual currents of the time through both his paintings and his occasional writings. His studio in Catskill became a destination for fellow artists and admirers, solidifying his position as a central figure in American culture.

Later Years, Final Works, and Untimely Death

In 1836, Cole married Maria Bartow and settled permanently in Catskill, New York, in a house known as Cedar Grove (now the Thomas Cole National Historic Site). He continued to paint prolifically, balancing commissions for landscapes with his more personal allegorical projects. He undertook a second trip to Europe in 1841-1842.

In his later years, Cole embarked on another ambitious religious allegory, The Cross and the World. Intended as a multi-part series exploring two contrasting spiritual paths – one worldly, one spiritual – it remained unfinished at the time of his death. The existing studies and paintings suggest a continuation of the profound spiritual themes that characterized The Voyage of Life.

Tragically, Cole's life was cut short. While working on The Cross and the World, he contracted pleurisy (often described as pneumonia). He died suddenly on February 11, 1848, at his home in Catskill, at the age of only 47. His death sent shockwaves through the American art world. A major memorial exhibition was organized in New York City, and his friend William Cullen Bryant delivered a moving funeral oration, cementing Cole's status as a foundational figure in American art and culture.

Cole in Collections and the Market

Thomas Cole's works are held in major museum collections across the United States and internationally. Key institutions housing significant paintings include the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (The Voyage of Life series), the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (The Oxbow, views of Mount Chocorua), the New-York Historical Society (The Course of Empire series), the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford (which holds many works due to Daniel Wadsworth's patronage), the Toledo Museum of Art (The Architect's Dream), the Albany Institute of History & Art (Romantic Landscape with Ruined Tower), and the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College (The Past, The Present).

His home and studio, Cedar Grove in Catskill, New York, is preserved as the Thomas Cole National Historic Site. It serves as a museum and study center dedicated to his life and work, housing artifacts, archives, and rotating exhibitions, often featuring his paintings or those of artists he influenced.

Cole's paintings appear periodically on the art market, often commanding high prices, reflecting his historical importance and enduring appeal. While major allegorical series rarely come up for sale, individual landscapes and studies are auctioned through major houses like Sotheby's and Christie's. Records indicate works were sold even in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and exhibitions like one associated with the Jack Warner Foundation have featured his works for sale more recently. Reproductions and prints based on his famous works, like The Voyage of Life, remain popular, demonstrating his continued cultural resonance.

Enduring Significance: Father of American Landscape

Thomas Cole's legacy is multifaceted and profound. He is rightly hailed as the founder of the Hudson River School and the "father of American landscape painting." More than just depicting scenery, he invested the American landscape with symbolic weight, making it a subject worthy of high art and national pride. His unique synthesis of detailed observation, Romantic emotion, and moral allegory created a powerful artistic language that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and shaped the course of American art for decades.

His influence extended beyond painting; his writings and the implicit messages in his art contributed to a growing awareness of the value of wilderness and the potential dangers of unchecked development, prefiguring the later conservation movement. He helped articulate a vision of America rooted in the unique character of its natural environment, contributing significantly to the formation of a distinct American cultural identity in the 19th century.

Though artistic styles evolved, Cole's pioneering vision endured. He demonstrated that an American artist could engage with grand themes, rivaling European traditions while remaining true to the specifics of the New World experience. His exploration of the complex interplay between humanity, nature, history, and faith continues to captivate viewers, securing his place as one of the most important and visionary artists in American history. His canvases remain potent reminders of the beauty and fragility of the natural world and the enduring human quest for meaning within it.