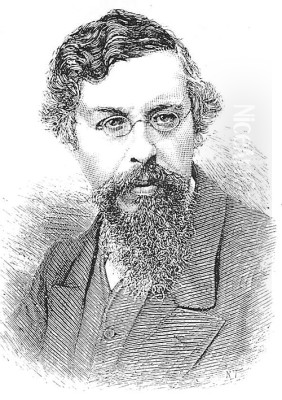

William Collingwood Smith stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of nineteenth-century British art. Born in Greenwich on December 10, 1815, and passing away at Brixton Hill on March 15, 1887, his life spanned a period of immense change and development in the art world. He distinguished himself primarily as a highly accomplished watercolour painter, celebrated for his evocative landscapes and detailed architectural studies. His dedication to the medium and his long association with the prestigious Society of Painters in Water Colours cemented his reputation among his peers and patrons.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Smith's entry into the world of art was somewhat unconventional for his time. His father held a position as a clerk in the Admiralty but was also an amateur painter, suggesting an early exposure to artistic pursuits within the family home in Greenwich. Despite this background, William Collingwood Smith did not follow a traditional path of academic training. He was largely self-taught, developing his skills through personal observation, practice, and an innate sensibility for visual representation.

His formal instruction was limited but significant. He received lessons, albeit briefly, from James Duffield Harding (J.D. Harding), a prominent landscape painter and lithographer known for his influential drawing manuals and his mastery of foliage representation. Harding's emphasis on capturing the structure and texture of nature likely left an impression on the young Smith, complementing his own developing style. This period of study, however short, provided a valuable connection to the established practices and theories of landscape art prevalent in Britain at the time. Smith's ability to achieve professional recognition primarily through self-direction speaks volumes about his dedication and natural talent.

The Development of a Distinctive Style

Early in his career, Smith showed an affinity for marine subjects, perhaps influenced by his upbringing in maritime Greenwich. However, his artistic focus soon broadened to encompass the wider scope of landscape and architectural views, which would become the hallmarks of his mature work. He worked predominantly in watercolour, a medium that enjoyed immense popularity and prestige in Britain during the nineteenth century, thanks in part to the legacy of artists like Thomas Girtin and J.M.W. Turner.

Smith developed a distinctive watercolour technique characterized by careful draughtsmanship, a nuanced understanding of light and atmosphere, and a keen eye for detail. He excelled at rendering the textures of stone, foliage, and water, bringing his scenes to life with a sense of immediacy and place. While grounded in the topographical tradition exemplified by earlier artists such as Paul Sandby, Smith's work often possessed a more atmospheric and sometimes romantic quality, capturing specific moods and moments in time. His handling of light, whether depicting the clear sunshine of an Italian scene or the softer, more diffused light of the British Isles, was particularly adept.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

William Collingwood Smith's extensive body of work covers a range of subjects, primarily landscapes drawn from his travels in Britain and continental Europe. Several works stand out as representative of his skill and artistic interests. Cader Idris, a depiction of the Welsh mountain, showcases his ability to capture the grandeur and specific character of a location. Rendered in subtle grey tones and with meticulous attention to the rocky terrain and vegetation, the work evokes a sense of serene, almost mysterious, natural beauty.

His travels abroad provided rich material. Works like The Rock of Lorelei and River Bank near a Castle on the Rhine reflect the Romantic fascination with dramatic European scenery. His depictions of Italy, such as Ruins in Italy, demonstrate his interest in classical antiquity and the picturesque decay of historical sites integrated within the landscape. This blending of natural scenery with architectural elements, often imbued with historical resonance, was a recurring theme.

A piece titled Impression of a Venetian Canal is particularly noteworthy. While Smith was not an Impressionist in the French sense, this work's title and likely execution suggest an interest in capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere on water and architecture, focusing on sensation rather than minute detail. This aligns with broader shifts in artistic perception occurring during the later nineteenth century, even if Smith's overall style remained more rooted in established watercolour traditions. His British scenes, including Harvest Scene, Ilfracombe, and Near Barmouth, celebrate the varied landscapes of his homeland with sensitivity and skill.

Professional Life and Affiliations

Smith's talent did not go unnoticed within the London art establishment. He began exhibiting his works widely, gaining exposure at prestigious venues such as the Royal Academy (R.A.), the British Institution (B.I.), and the Society of British Artists (S.B.A.) at Suffolk Street. However, his most significant professional affiliation was with the Society of Painters in Water Colours, often referred to as the "Old Watercolour Society" (O.W.S.) to distinguish it from newer rival groups. This society was the leading institution dedicated to the medium in Britain.

He was elected an Associate of the O.W.S. in 1843 and achieved full membership in 1849. This recognition placed him among the elite watercolourists of his day, alongside esteemed colleagues like David Cox, Peter De Wint, Copley Fielding, and Samuel Prout. Within the society, Smith was highly respected, serving as its Treasurer for a remarkable twenty-five years, from 1854 until 1879. His long tenure in this role underscores his commitment to the organization and the trust placed in him by his fellow artists. His regular contributions to the society's exhibitions were a mainstay of his career.

Teaching and Wider Influence

Beyond his personal artistic practice, William Collingwood Smith made a significant contribution to art education. He established and ran a successful art school at Wyndham Lodge in London. His reputation attracted a diverse range of students, including aspiring professional artists, dedicated amateurs seeking to improve their skills, and, notably, officers from the military and navy. Teaching drawing and watercolour was considered a valuable accomplishment for gentlemen, and Smith's instruction was clearly highly regarded.

His role as an educator extended his influence, helping to shape the artistic abilities and appreciation of a generation of students. By imparting the techniques and principles he had mastered, particularly in the challenging medium of watercolour, he played a part in sustaining the vitality of the British landscape tradition. His teaching activities complemented his exhibition record and society involvement, painting a picture of a well-rounded and respected figure in the Victorian art world.

Connections to Contemporaries

Situating William Collingwood Smith within the broader context of nineteenth-century British art reveals his place amidst a vibrant and evolving scene. His initial training under James Duffield Harding connected him to established pedagogical methods. His membership in the O.W.S. brought him into regular contact with the leading watercolourists mentioned earlier, such as Cox, De Wint, Fielding, and Prout, as well as others like William Henry Hunt, known for his meticulous still lifes, and later popular figures like Myles Birket Foster.

While Smith's detailed and atmospheric landscapes shared common ground with many contemporaries, his style remained distinct. He did not embrace the radicalism of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, whose members like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais were challenging artistic conventions during the middle part of Smith's career. Nor did his work fully anticipate the bolder experiments of later British Impressionists. His art can be seen as occupying a respected position within the mainstream of Victorian landscape painting, influenced by Romantic sensibilities but executed with a careful technique that appealed to the tastes of the time. The pervasive influence of the critic John Ruskin, who championed detailed observation of nature, also formed part of the intellectual backdrop against which Smith worked, even if direct connections are not documented. His contemporaries mentioned in source documents include Francis Vyvyan Jago Arundale and George Balmer, further illustrating the network of artists active during his era.

Personal Life and Character

While much of the focus remains on his artistic career, glimpses into William Collingwood Smith's personal life add depth to his biography. He was married twice. His first marriage was to Susanna Watson, with whom he had a son, John Alfred Smith. Following Susanna's passing, he married Louisa Trickett, and they had a son named William Harding Smith, the middle name possibly a tribute to his former teacher.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing aspects of his personal life, hinting at a multifaceted personality beyond the dedicated artist, was his involvement in amateur theatricals. Reports indicate he took on roles portraying a variety of dramatic, often villainous characters, including devils, bandits, assassins, monsters, and pirates. This suggests a playful or expressive side, perhaps offering a creative outlet distinct from the more restrained and observational nature of his painting. It paints a picture of an individual engaged with different forms of cultural expression.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

William Collingwood Smith remained active as an artist for much of his life. He continued to exhibit and maintain his connections within the art world. He passed away at his home in Brixton Hill, South London, on March 15, 1887, at the age of 71. He was buried in West Norwood Cemetery, a location known for its significant Victorian monuments and the final resting place of many notable figures from the era.

His artistic legacy endured beyond his death. His works continued to be appreciated and collected. They found homes in both private collections and public institutions, ensuring their accessibility for future generations. The efforts of later collectors, such as John Harbold, who gathered originals and reproductions, and researchers like Betty Griffin, have helped to preserve knowledge of his life and work.

Smith's contribution to British art was recognized in subsequent exhibitions, such as the show A British Sensibility: The Landscape and Watercolour Tradition 1750-1950, which included his painting Cader Idris. Such inclusions reaffirm his position within the historical narrative of British watercolour painting. His legacy lies in his substantial output of high-quality watercolours, his role as an influential teacher, and his dedicated service to the Old Watercolour Society. He represents a significant strand of Victorian art, characterized by technical proficiency, sensitivity to landscape, and a deep engagement with the watercolour medium.

Conclusion

William Collingwood Smith navigated the nineteenth-century British art world with considerable success. Primarily self-taught yet reaching the highest echelons of the watercolour establishment through his membership and treasurership of the O.W.S., he created a significant body of work admired for its technical skill and atmospheric beauty. His landscapes, drawn from Britain and Europe, captured both the specifics of place and the evocative qualities of light and mood. As an artist, exhibitor, society stalwart, and respected teacher, Smith made a lasting contribution to the Victorian art scene, leaving behind a legacy as a master of the watercolour medium whose works continue to be appreciated for their quiet charm and accomplished execution. He remains an important figure for understanding the depth and diversity of British landscape painting during his time.