The annals of art history are rich with figures whose contributions, while significant, may not always echo with the same global resonance as those of their most famous contemporaries. Juan José Gárate y Clavero, an Aragonese painter and educator, stands as one such artist whose career unfolded during a pivotal era in Spanish art—a time of transition from entrenched academic traditions to the burgeoning currents of modernity. While detailed monographs and extensive exhibitions dedicated solely to Gárate y Clavero are not as commonplace as for some of his peers, his life and work offer a valuable lens through which to examine the regional artistic developments and the broader cultural milieu of Spain from the late 19th to the early 20th century.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Juan José Gárate y Clavero was born in 1870, a period when Spain was navigating complex political and social changes that would inevitably influence its cultural expression. His artistic journey began in Zaragoza, the historic capital of Aragon, a region with a rich artistic heritage. It was here, likely at the Escuela de Bellas Artes de Zaragoza, that he would have received his initial training. These provincial academies, while perhaps not always possessing the same prestige as the central institution in Madrid, played a crucial role in nurturing local talent and disseminating artistic knowledge across the country.

The traditional academic curriculum of the time would have emphasized rigorous training in drawing from plaster casts and live models, the study of anatomy, perspective, and art history, particularly focusing on the masters of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. This foundational education was designed to equip aspiring artists with the technical skills necessary for careers in portraiture, historical painting, and religious commissions, which were still highly valued.

Roman Sojourn and Professorial Return

A significant step for many ambitious Spanish artists of this era was a period of study in Rome. The Eternal City, with its unparalleled access to classical antiquities and Renaissance masterpieces, was considered an essential finishing school. Gárate y Clavero, following this well-trodden path, furthered his studies in Rome. While the provided information mentions the "San Fernando Academy in Rome," it's more probable he was associated with the Academia de España en Roma (Spanish Academy in Rome), a prestigious institution that offered scholarships to promising Spanish artists, or simply resided and studied independently, drawing inspiration from the city's artistic wealth. The Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, a cornerstone of Spanish art education, is located in Madrid and would have likely been an institution he was familiar with, perhaps even attended before or after his Italian experience, or whose curriculum influenced his own studies.

Upon his return to Spain, Gárate y Clavero embraced a career not only as a practicing artist but also as an educator. He became a professor at the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Zaragoza, a position that would have allowed him to shape and influence a new generation of Aragonese artists. His role as an academician underscores a commitment to the principles of art education and the perpetuation of artistic skill and knowledge within his native region. He passed away in 1931, his life spanning a dynamic period of artistic evolution.

Artistic Style and Potential Oeuvre

Specific titles of Juan José Gárate y Clavero's representative works are not extensively documented in readily accessible sources, which makes a detailed analysis of his stylistic evolution challenging. However, based on his academic training in Zaragoza and Rome, and his career as a professor during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we can infer the likely characteristics of his artistic output.

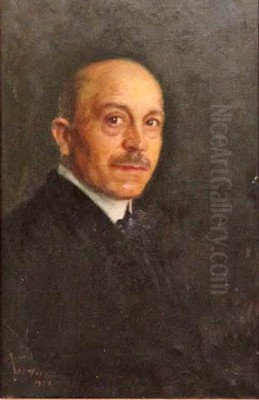

His work would almost certainly have been grounded in the principles of academic realism. This tradition emphasized verisimilitude, technical polish, and often, narrative clarity. Portraiture was a staple for academically trained artists, providing a consistent source of commissions. It is highly probable that Gárate y Clavero produced portraits of local dignitaries, bourgeois families, and perhaps fellow artists or intellectuals in Zaragoza.

Furthermore, the influence of costumbrismo—the depiction of everyday life, local customs, and regional types—was pervasive in Spanish art of this period. Aragonese themes, landscapes, and figures would have offered rich subject matter. Artists often found both critical and popular success with scenes that celebrated regional identity, and Gárate y Clavero may well have contributed to this genre, capturing the unique character of his homeland.

While firmly rooted in academic tradition, it is unlikely Gárate y Clavero would have been entirely immune to the newer artistic currents sweeping across Europe and Spain. The late 19th century saw the rise of plein-air painting and a greater interest in capturing the effects of light and atmosphere, partly influenced by French Impressionism. In Spain, this manifested most brilliantly in the luminismo of Joaquín Sorolla, whose sun-drenched Valencian beach scenes captivated audiences. While perhaps not fully embracing Impressionist techniques, many Spanish realists adopted a brighter palette and a looser brushstroke in response to these trends.

The Spanish Artistic Context: A Nation in Transition

To fully appreciate the environment in which Gárate y Clavero worked, it is essential to consider the broader Spanish artistic scene of his time. This was an era of immense creativity and stylistic diversity, marked by a tension between the established academic order and the forces of innovation.

The Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid remained a powerful institution, setting standards and influencing taste through its exhibitions and educational programs. Artists like Francisco Pradilla Ortiz, known for his grand historical paintings such as "The Surrender of Granada," represented the pinnacle of academic achievement and enjoyed considerable state patronage. Another prominent figure from this academic tradition was José Villegas Cordero, who, after a successful career in Rome, became Director of the Prado Museum, and whose works ranged from historical scenes to vibrant genre paintings.

However, the late 19th century also witnessed a growing desire for renewal. Mariano Fortuny, though he died relatively young in 1874, had already left an indelible mark with his dazzling technique and vibrant depictions of genre scenes, often with an Orientalist flavor. His work inspired a generation of artists to seek greater brilliance in color and light.

The influence of Impressionism, while perhaps not as directly adopted in Spain as in France, was nonetheless felt. Darío de Regoyos was one of the few Spanish artists who consistently explored Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist techniques, often depicting the landscapes and social realities of northern Spain. Aureliano de Beruete, a distinguished intellectual and landscape painter, also absorbed Impressionist influences, creating refined and atmospheric views of Castile.

The turn of the century saw the flourishing of Modernismo (the Spanish equivalent of Art Nouveau and Jugendstil), particularly in Catalonia. Barcelona became a vibrant center for this movement, which sought to break with academic conventions and embrace new forms of expression across art, architecture, and design. Santiago Rusiñol and Ramón Casas were leading figures of Catalan Modernismo, known for their evocative paintings, posters, and their role in the cultural life of Barcelona, particularly at the Els Quatre Gats café. Rusiñol's Symbolist-infused garden scenes and Casas's elegant portraits defined an era.

While Modernismo was most prominent in Catalonia, its influence extended to other regions. Artists across Spain were experimenting with new aesthetic ideas, decorative forms, and a more subjective approach to art. Joaquín Mir Trinxet, another Catalan, pushed landscape painting towards an almost abstract expression of color and light, creating works of stunning visual intensity. Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa, with his opulent colors and decorative style, often depicting vibrant scenes of Parisian nightlife or Spanish folklore, gained international acclaim.

In Andalusia, Julio Romero de Torres developed a highly distinctive style, blending Symbolism with a deep engagement with Andalusian tradition and archetypes, often creating enigmatic and sensual portrayals of women. His work, while unique, resonated with a broader Spanish search for national and regional identity in art.

Meanwhile, the towering figure of Ignacio Zuloaga offered a contrasting vision to the sunlit optimism of Sorolla. Zuloaga's powerful, often somber, depictions of Spanish life, bullfighters, and stark landscapes drew on the tradition of Spanish Golden Age masters like El Greco and Goya. He presented a more austere and, some argued, more profound vision of Spain, which found favor both domestically and internationally.

This rich and varied artistic panorama formed the backdrop for Gárate y Clavero's career. As a professor in Zaragoza, he would have been tasked with navigating these diverse currents, imparting traditional skills while also acknowledging the evolving definition of art. His students would have been exposed, through publications, exhibitions, and perhaps travel, to these varied artistic expressions.

The Role of Regional Art Centers

Zaragoza, while not Madrid or Barcelona, possessed its own cultural vitality. Regional art schools and societies played a crucial role in fostering artistic life outside the major metropolitan centers. They provided exhibition opportunities, fostered a sense of community among artists, and helped to cultivate local patronage. Gárate y Clavero's position within this framework would have made him a significant figure in the Aragonese art scene.

Artists in regional centers often faced the challenge of balancing local traditions and expectations with the desire to engage with broader national and international trends. The extent to which Gárate y Clavero's work reflected a distinctly Aragonese character, or how he synthesized academic principles with more contemporary influences, remains a subject for deeper investigation, ideally through a comprehensive study of his surviving works.

The early 20th century also saw the emergence of the avant-garde. While Gárate y Clavero's career largely predates the full impact of Cubism and Surrealism in Spain, the seeds of these radical movements were being sown during the later part of his life. Young Spanish artists like Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, and later Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró, would go on to revolutionize art in the 20th century, many of them initially passing through the academic system before breaking away dramatically. This underscores the dynamic tension of the era—a period of looking back to tradition while simultaneously lunging towards an uncharted future.

Legacy and the Scarcity of Information

The provided information indicates that Juan José Gárate y Clavero was indeed a painter and that a painting by him exists (as per source 3 of the initial query), though its title and current location are not specified. This scarcity of readily available, detailed information about his specific works or personal anecdotes is not uncommon for artists who may have enjoyed regional prominence but did not achieve the same level of national or international fame as some of their contemporaries.

His legacy likely resides primarily in his contributions to the artistic life of Zaragoza, both as a creator and an educator. The impact of a dedicated professor can be profound, shaping the skills and artistic visions of numerous students who then carry that influence forward in their own careers.

The fact that his death is recorded as 1931 places his final years at a time when Spain was on the cusp of major political upheaval, with the fall of the monarchy and the establishment of the Second Republic. This period of intense social and political change also had a profound impact on the arts, fostering new debates about the role of art in society.

Further research in Aragonese archives, museum collections in Zaragoza, and local art historical publications would be necessary to construct a more complete picture of Juan José Gárate y Clavero's oeuvre, his specific stylistic contributions, and his influence on the artistic community of his time. Such research could potentially uncover more of his paintings, critical reviews of his work from contemporary periodicals, and perhaps even personal documents or correspondence that could shed more light on his life and artistic philosophy.

Conclusion: A Figure Meriting Further Exploration

Juan José Gárate y Clavero (1870-1931) represents a category of artist essential to the fabric of any national art history: the dedicated regional painter and educator. While not possessing the widespread fame of a Sorolla, a Zuloaga, or a Picasso, his career as a student in Zaragoza and Rome, and later as a professor in his native Aragon, places him firmly within the artistic currents of his time. His work, likely rooted in academic realism but potentially touched by the evolving aesthetic sensibilities of the era, contributed to the cultural landscape of Zaragoza.

His life spanned a period of extraordinary artistic ferment in Spain, from the lingering dominance of 19th-century academicism to the vibrant explorations of Luminism, Modernismo, and the early stirrings of the avant-garde. Understanding figures like Gárate y Clavero enriches our appreciation of this complex period, reminding us that artistic vitality is not confined to major metropolitan centers but thrives also in regional communities, nurtured by artists who dedicate their lives to creation and education. The pursuit of more detailed information on his specific works and a deeper analysis of his artistic contributions would undoubtedly offer further insights into the rich tapestry of Spanish art at the turn of the 20th century.