Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (1553-1608) stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Spanish art, particularly renowned for his role as a court painter during the reigns of Philip II and Philip III. His meticulous and dignified portraits captured the austere grandeur of the Spanish Habsburg court, bridging the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. Born in Valladolid, Pantoja's career unfolded primarily in Madrid, the vibrant center of Spanish royal power and artistic patronage. His work not only provides invaluable historical records of the monarchy and aristocracy but also reflects the evolving artistic tastes and cultural values of Spain's Siglo de Oro.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz was born in Valladolid in 1553. While details of his earliest years remain somewhat obscure, it is firmly established that his artistic journey began in Madrid under the tutelage of Alonso Sánchez Coello (c. 1531-1588). Sánchez Coello himself was a distinguished court painter, having studied under Anthonis Mor (also known as Antonio Moro), a Flemish artist who had brought a new level of sophistication and psychological depth to portraiture at the Spanish court. This lineage of master-pupil relationships was crucial in shaping the dominant style of Spanish royal portraiture for decades.

Under Sánchez Coello, Pantoja would have learned the meticulous techniques required for court portraiture: the precise rendering of rich fabrics, intricate lace, and dazzling jewelry, as well as the ability to convey a sense of status and decorum. The workshop of a court painter was a busy enterprise, and apprentices like Pantoja would have been involved in various stages of painting, from preparing canvases and grinding pigments to painting less critical parts of compositions or making copies. This rigorous training instilled in him a profound attention to detail and a mastery of likeness that would become hallmarks of his mature style.

Ascendancy at the Spanish Court

Pantoja's independent career began to flourish in the 1580s. He married in 1585, a step that often coincided with an artist establishing their own workshop and seeking greater professional autonomy. A significant turning point came with the death of his master, Alonso Sánchez Coello, in 1588. Pantoja, by then a seasoned and trusted artist, effectively took over Sánchez Coello's workshop and inherited his esteemed position as a painter to King Philip II.

Serving Philip II, a monarch known for his piety, diligence, and somewhat somber demeanor, required an artistic style that emphasized gravitas and formality. Pantoja excelled in this, producing portraits that conveyed the king's authority and the unyielding nature of the Spanish monarchy. His portraits from this period are characterized by their sober palettes, often dominated by the blacks and dark colors favored by the Spanish Habsburgs, relieved by the glint of gold chains or the white of a ruff. The sitters are typically presented with a formal, somewhat distant expression, reflecting the hierarchical nature of the court.

Continued Service under Philip III

Upon Philip II's death in 1598, his son Philip III ascended to the throne. Pantoja de la Cruz seamlessly transitioned into serving the new monarch, and his position was formally confirmed when he was appointed pintor de cámara (chamber painter or court painter) to Philip III in 1596, even before Philip II's death, indicating the high regard in which he was held. He continued in this prestigious role until his own death in Madrid on October 26, 1608.

Under Philip III, the courtly atmosphere, while still formal, saw a slight shift towards greater opulence, which is subtly reflected in Pantoja's later works. He painted numerous portraits of Philip III, his queen, Margaret of Austria, and their children, including the young Prince Philip (the future Philip IV) and the Infanta Anne of Austria (future Queen of France). These royal commissions were not merely about capturing a likeness; they were powerful statements of dynastic continuity, wealth, and political power. Pantoja's ability to render the elaborate costumes and jewels with painstaking accuracy contributed significantly to this projection of majesty.

Artistic Style and Technique

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz's artistic style is a fascinating blend of inherited traditions and personal innovation, situated at the crossroads of late Mannerism and the emerging Baroque. His work is primarily characterized by its meticulous realism, particularly in the rendering of textures and details.

Detail and Realism: Pantoja's depiction of fabrics – silks, velvets, brocades – and the intricate patterns of lace and embroidery is astonishing. He paid equally close attention to jewelry, armor, and other accoutrements of status, making his paintings valuable documents of period costume and material culture. This almost tactile quality of surfaces was a legacy from Flemish painters like Anthonis Mor, transmitted through Sánchez Coello.

Composition and Pose: His compositions are generally formal and hierarchical. Figures are often depicted full-length or three-quarter length, standing or seated, with a sense of stillness and composure. The poses are dignified, rarely dynamic, emphasizing the sitter's status rather than their personality in a more informal sense. This approach was well-suited to the rigid etiquette of the Spanish court.

Use of Light and Color: Pantoja employed a controlled use of light, often creating a subtle chiaroscuro that modeled faces and forms effectively. While his palette could be rich, particularly in depicting jewels and certain fabrics, it was often dominated by the somber blacks, grays, and dark reds favored by the Spanish Habsburgs. This created an atmosphere of seriousness and austerity, though his rendering of gold and silver embroidery could add points of brilliance. His lighting was generally more even and less dramatic than the tenebrism that would later be popularized by Caravaggio and his Spanish followers like Jusepe de Ribera.

Psychological Insight (or Lack Thereof): Compared to later masters like Velázquez, Pantoja's portraits are often seen as less psychologically penetrating. The emphasis was more on the external trappings of power and the official persona of the sitter rather than an intimate exploration of their character. Faces often bear a cool, impassive, or slightly melancholic expression, which was in keeping with the Spanish ideal of gravedad (gravity, seriousness). However, this should not be mistaken for a lack of skill; rather, it was a stylistic choice dictated by the conventions and expectations of his patrons.

Mannerist Influences: Some art historians detect Mannerist tendencies in Pantoja's work, such as a certain elongation of figures, a coolness in the emotional tone, and a highly polished finish. The meticulous attention to surface detail and the somewhat stylized representation of figures can be linked to broader European Mannerist trends, as seen in the work of artists like Bronzino in Italy.

Representative Works

Pantoja de la Cruz was a prolific painter, and many of his works survive, primarily in Spanish collections like the Prado Museum in Madrid and the Escorial.

Royal Portraits:

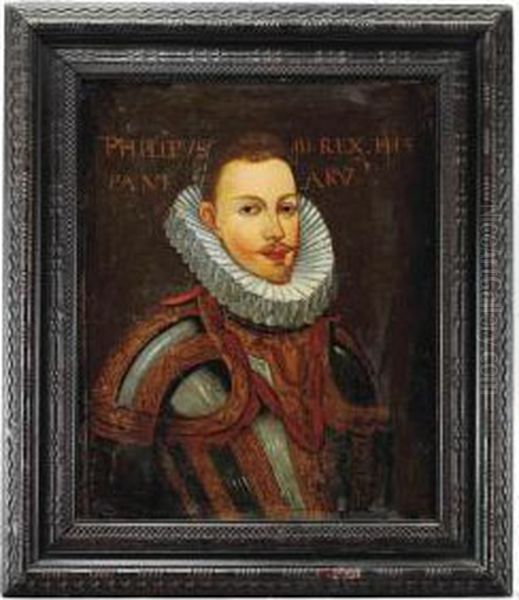

_Portrait of Philip II_ (c. 1590s, various versions): These portraits depict the aging monarch with the characteristic sobriety and dignity expected. One notable example is the full-length portrait of Philip II in armor, now in the Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, which emphasizes his role as a defender of the faith.

_Portrait of Philip III_ (e.g., 1606, Prado Museum, Madrid): Pantoja painted Philip III numerous times. The 1606 portrait in the Prado shows the king in black, adorned with the Order of the Golden Fleece, his expression serious and his posture regal. Another significant work is Philip III in Court Dress (1605, Prado Museum), showcasing the elaborate attire of the period.

_Portrait of Queen Margaret of Austria_ (e.g., c. 1605-1607, Prado Museum, Madrid): Consort of Philip III, Queen Margaret was a frequent subject. Pantoja captured her in sumptuous gowns, often adorned with an abundance of pearls and jewels, emphasizing her fertility and dynastic importance. A fine example is the Portrait of Margaret of Austria, Queen of Spain (c. 1605, Royal Collection Trust, UK).

_Portrait of Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia_ (c. 1599, Prado Museum, Madrid): Philip II's favorite daughter, Isabella Clara Eugenia, was painted by Pantoja, often with a severity and piety that mirrored her father's. This particular portrait shows her in austere black attire, reflecting her status as sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands alongside her husband, Archduke Albert of Austria.

_Portrait of Prince Philip (later Philip IV) as a Child_ (c. 1607, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna): This charming portrait depicts the future king as a young boy, already dressed in formal attire, hinting at his destined role.

_Portrait of Anne of Austria, Queen of Spain_ (wife of Philip II) (various versions): Pantoja continued the tradition of portraying Philip II's fourth wife, often emphasizing her regal bearing and the richness of her attire.

Portraits of the Nobility:

Beyond the immediate royal family, Pantoja also painted members of the high nobility, such as the Duke of Lerma, Philip III's powerful favorite. These portraits, while perhaps allowing for slightly more individuality, still adhered to the formal conventions of court portraiture. An example is the Portrait of Don Diego de Valdivia y Mendoza (Prado Museum).

Religious Paintings

While Pantoja de la Cruz is primarily celebrated for his portraiture, he also undertook religious commissions. These works, though fewer in number or less frequently discussed than his portraits, demonstrate his versatility and his engagement with the devotional currents of his time. Spain, as a bastion of the Counter-Reformation, had a strong demand for religious art that was both doctrinally sound and emotionally engaging.

His religious paintings often display a similar meticulousness in detail and a rich, though sometimes somber, color palette. Works such as _The Birth of the Virgin_ (1603, Prado Museum, Madrid) showcase his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions. In this painting, the scene is depicted with a sense of solemnity and reverence, the figures rendered with a tangible solidity. Other religious subjects attributed to him include depictions of saints, such as _Saint Augustine_ and _Saint Nicholas of Tolentino_ (both in the Prado Museum, from the Colegio de Doña María de Aragón series, where El Greco also contributed major works).

His style in these religious works sometimes shows a greater leaning towards naturalism than his more stylized court portraits, perhaps influenced by the broader European trend towards a more direct and emotionally accessible religious art, a path that artists like Caravaggio were forging, albeit with more dramatic intensity. Pantoja's religious works, however, generally maintain a sense of decorum and restraint characteristic of Spanish piety.

The English Connection: Diplomatic Portraits

A fascinating episode in Pantoja's career involved a diplomatic exchange with England. Following the Treaty of London in 1604, which ended the long Anglo-Spanish War, gifts were exchanged between the courts of Philip III and James I of England. As part of this reconciliation, Pantoja de la Cruz was commissioned to paint portraits of the Spanish royal family to be sent to the English king.

Between 1604 and 1605, he produced portraits of Prince Philip (the future Philip IV), Queen Margaret, and the Infanta Anne. These works served not only as artistic representations but also as political tools, symbolizing the newfound peace and the potential for future alliances, possibly through marriage. The portraits sent to England, some of which are now in the British Royal Collection, would have introduced Pantoja's distinctively Spanish style to an English audience more accustomed to the portraiture of artists like Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger or Robert Peake the Elder. This commission underscores Pantoja's status as Spain's leading court painter, entrusted with representing the monarchy on an international stage.

Influences, Contemporaries, and Successors

Pantoja's art cannot be understood in isolation. He was part of a rich artistic environment.

Alonso Sánchez Coello: His most direct influence, providing the foundational style of meticulous realism and courtly decorum.

Anthonis Mor (Antonio Moro): The ultimate source for much of the Spanish court portraiture style, Mor's work for Philip II set a standard for dignified, realistic, and psychologically astute (though formal) portraiture.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio): The great Venetian master had a profound impact on Spanish royal collecting and artistic taste, particularly through his portraits of Charles V and Philip II. His rich color, masterful handling of paint, and ability to convey majesty were admired and emulated. While Pantoja's technique was tighter than Titian's, the ideal of regal representation was certainly influenced by the Venetian.

Sofonisba Anguissola: This Italian noblewoman and painter served as a lady-in-waiting and court painter to Queen Elisabeth of Valois, Philip II's third wife. Her sensitive portraits, particularly of the royal children, were part of the artistic milieu in which Sánchez Coello and later Pantoja worked.

El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos): A contemporary of Pantoja, El Greco worked primarily in Toledo and developed a highly personal, spiritual, and anti-naturalistic style that differed greatly from the official court portraiture of Pantoja. While Philip II did not favor El Greco's style for major commissions at El Escorial, El Greco did execute some portraits and religious works for patrons in Madrid, and both artists contributed to the series of paintings for the Colegio de Doña María de Aragón.

Italian Mannerists: Artists like Bronzino, with their polished surfaces, elongated figures, and cool detachment, represent a broader European trend that finds echoes in Pantoja's formality.

Flemish Tradition: The detailed realism of Early Netherlandish painting (e.g., Jan van Eyck) continued to resonate in the meticulous approach of many 16th-century portraitists, including those in Spain.

Pantoja, in turn, influenced the next generation. His pupils included Francisco López, and his style set a precedent for subsequent court painters. Bartolomé González y Serrano (1564-1627) largely continued Pantoja's formal style of portraiture at the court of Philip III and in the early years of Philip IV's reign. While the arrival of Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) at court in the 1620s would revolutionize Spanish portraiture with his looser brushwork, profound psychological depth, and unparalleled naturalism, Velázquez still built upon the established tradition of Habsburg representation that Pantoja had so capably maintained. Other notable Spanish painters of the era, though perhaps not directly influenced, include the still-life master Juan Sánchez Cotán and the early Baroque naturalist Francisco Ribalta.

Personal Life and Final Years

Details about Juan Pantoja de la Cruz's personal life beyond his marriage in 1585 are scarce, as is common for artists of this period unless they were figures of broader social or intellectual prominence like Peter Paul Rubens. His life appears to have been dedicated to his demanding role as a court painter. This position required not only artistic skill but also an understanding of court etiquette and the ability to navigate the complex relationships within the royal circle.

He remained active as a painter for the crown until his death. Juan Pantoja de la Cruz passed away in Madrid on October 26, 1608. His death marked the end of an era in Spanish court portraiture, though his influence would linger until new styles and new masters emerged.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Initially, Pantoja's work, like that of Sánchez Coello, was sometimes overshadowed by the towering figures of El Greco and Velázquez. Some later critics, particularly those valuing more expressive or dynamic art, found his style somewhat rigid or overly formal. However, art historical scholarship has increasingly recognized his crucial role and artistic merit.

Pantoja de la Cruz is now considered one of the most important Spanish painters of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His contributions are manifold:

Continuity of a Tradition: He successfully maintained and developed the style of formal court portraiture established by Mor and Sánchez Coello, providing a consistent visual representation of the Spanish Habsburg monarchy during a critical period.

Historical Documentation: His paintings are invaluable historical documents, offering detailed insights into the appearance of key historical figures, court fashion, and the symbols of power.

Artistic Skill: His technical mastery, particularly in rendering textures and details, is undeniable. While perhaps not as innovative as El Greco or as revolutionary as Velázquez, his skill within the conventions he worked was exceptional.

Influence: He bridged the gap between Sánchez Coello and the painters of the full-blown Baroque era in Spain, influencing his pupils and setting a standard for his immediate successors.

His works are prominently displayed in major museums, most notably the Prado Museum in Madrid, but also in El Escorial, the Royal Collection in the UK, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and other significant collections worldwide. He is recognized as a key exponent of the Spanish School, embodying the gravity, dignity, and meticulousness that characterized much of its output during the Siglo de Oro.

Conclusion

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz was more than just a painter of kings and queens; he was a chronicler of an epoch, a master craftsman whose art embodied the spirit of the Spanish Habsburg court. His portraits, with their solemn grandeur and exquisite detail, offer a compelling window into the world of Philip II and Philip III. While adhering to the strict conventions of court portraiture, Pantoja infused his work with a distinctive quality that has ensured his lasting place in the annals of Spanish art. As a vital link in the chain of Spanish court painters, his legacy is secure, his paintings continuing to fascinate scholars and art lovers alike with their depiction of a powerful dynasty and a bygone era of imperial splendor.