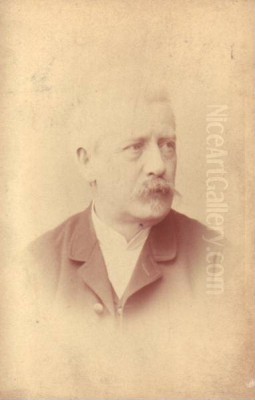

Julius Eduard Mařák stands as a pivotal figure in 19th-century Czech art, celebrated primarily for his evocative landscape paintings and his profound influence as an educator. His work captured the soul of the Bohemian forests and countryside, blending Romantic sensibilities with a keen observation of nature. As a professor at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, he nurtured a generation of artists who would further shape the course of Czech modernism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

While some older or less common sources might anachronistically place his birth in Reims, France, in 1803, the widely accepted and historically verified details indicate Julius Eduard Mařák was born on March 29, 1832, in Litomyšl, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). His early artistic inclinations were fostered in Prague, where he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts. There, he studied under figures like Christian Ruben, the then-director, and notably in the landscape class of Max Haushofer, a German painter who brought a Munich sensibility to Prague. Haushofer's emphasis on direct study from nature and Romantic landscape traditions left an indelible mark on the young Mařák.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Mařák, like many aspiring artists of his time, traveled to Munich in 1853. The Bavarian capital was a vibrant artistic hub, and Mařák further honed his skills, likely absorbing the influences of prominent landscape painters such as Eduard Schleich the Elder and Carl Rottmann, whose works were shaping the Munich school of landscape painting. This period was crucial for developing his technical proficiency and deepening his understanding of atmospheric effects and the poetic potential of landscape.

The Vienna Years: A Developing Career

Around 1855 or shortly thereafter, Mařák moved to Vienna, the imperial capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He would spend a significant portion of his career there, nearly three decades, before his eventual return to Prague in a professorial capacity. In Vienna, Mařák established himself as a respected artist and a sought-after drawing master, particularly among aristocratic circles. He continued to paint, focusing on landscapes that often depicted forest interiors, a theme that would become his hallmark.

During his Viennese period, Mařák's style matured. While early influences of the Biedermeier period, with its attention to detail and somewhat sentimental charm, can be discerned in his initial works, he increasingly moved towards a more Romantic and atmospheric depiction of nature. He was adept at capturing the play of light filtering through leaves, the misty depths of ancient forests, and the tranquil solitude of woodland scenes. His works from this era were exhibited and gained recognition, solidifying his reputation as a skilled landscape painter. He also engaged in graphic arts, producing illustrations that showcased his fine draughtsmanship.

Return to Prague: The Professorship and the Mařák School

A turning point in Mařák's career, and indeed for Czech landscape painting, came in 1887. He was appointed professor of landscape painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, succeeding his former teacher Max Haushofer. This appointment was significant, as it brought a highly accomplished and experienced artist back to his homeland to lead the next generation. The landscape studio he headed became affectionately known as the "Mařákova škola" (Mařák's School) and was a crucible for talent.

Mařák was a dedicated and inspiring teacher. He encouraged his students to develop their own individual styles while grounding them in rigorous observation of nature and solid technical skills. He would often take his students on plein-air excursions into the Bohemian countryside, particularly to areas like the Šumava forests or the Okoř region, instilling in them a deep appreciation for their native landscape. His pedagogical approach was instrumental in moving Czech landscape painting away from purely academic conventions towards a more personal and emotionally resonant interpretation of nature.

Many of his students went on to become prominent figures in Czech art. Among the most notable were Antonín Slavíček, who became a leading figure of Czech Impressionism and modern landscape painting; František Kaván, known for his lyrical winter landscapes; Alois Kalvoda, celebrated for his birch groves and atmospheric scenes; Otakar Lebeda, a prodigious talent whose life was tragically short; Josef Ullmann; and Ferdinand Engelmüller. Each of these artists, while developing unique paths, carried aspects of Mařák's teaching, particularly the emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and the poetic qualities of the landscape.

Artistic Style: Romanticism, Realism, and the Soul of the Forest

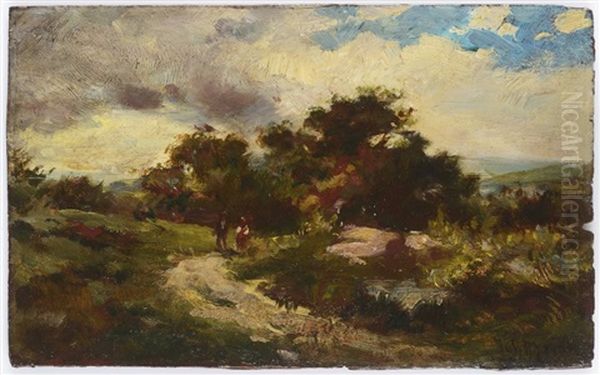

Julius Mařák's artistic style is primarily rooted in Romanticism, with strong elements of Realism in his meticulous observation of natural detail. He was less concerned with topographical accuracy for its own sake and more interested in conveying the emotional experience of being in nature. His forest interiors are not mere depictions of trees; they are immersive environments, often imbued with a sense of mystery, melancholy, or sublime tranquility.

The influence of the Barbizon School, though perhaps indirect, can be felt in his work – artists like Théodore Rousseau or Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña also found profound inspiration in forest scenes. Mařák shared their deep reverence for trees and their ability to capture the intricate play of light and shadow within dense woods. He was a master of rendering textures – the rough bark of ancient oaks, the delicate tracery of branches against the sky, the dampness of the forest floor.

His color palette was often subdued, favoring earthy tones, deep greens, and silvery greys, which contributed to the characteristic mood of his paintings. However, he could also capture the vibrant hues of autumn or the ethereal light of a moonlit night with great skill. A recurring motif in his work is the solitary figure, often small in scale, dwarfed by the grandeur of nature, emphasizing a Romantic sense of human insignificance before the sublime. He also created numerous illustrations and was noted for inventing a unique technique in this field, though specifics of this technique are not always detailed in general accounts.

Representative Works and Thematic Concerns

Mařák's oeuvre is extensive, comprising numerous oil paintings, drawings, and graphic works. Several pieces stand out as representative of his style and thematic preoccupations.

Forest Interiors: This was his most beloved subject. Works like Forest Interior with Deer (various versions exist) exemplify his ability to create a deep, receding space filled with filtered light and a palpable sense of stillness. The deer, often present, add a touch of life and wildness to the scene. Other titles like Forest Solitude, In the Depths of the Forest, or Moonlit Forest point to this central theme.

_Swampland Landscape_ (1880): This painting, mentioned in provided materials, showcases his skill in depicting specific, perhaps less conventionally picturesque, natural environments, capturing their unique atmosphere and ecological character.

Landscapes of Bohemia: Mařák painted various regions of his homeland, contributing to a growing sense of national identity through the depiction of the Czech landscape. His works often evoke a deep connection to the land.

_Provincial Street Scene_ and _Landscape_: These titles, also noted in provided information, suggest a broader range of subjects beyond just forest interiors, though the forest remained his dominant passion.

Decorative Works for the National Theatre: Mařák was among the artists, often referred to as the "National Theatre Generation" (which included painters like Mikoláš Aleš, František Ženíšek, and Vojtěch Hynais), who contributed to the decoration of this iconic Czech cultural institution. He designed paintings for the Royal Box (later Presidential Box), depicting Czech castles and landscapes, thus linking his art directly to the burgeoning national consciousness. The "Prague Castle Presidential Box decoration (1983)" mentioned in one source likely refers to a later appreciation or restoration related to these earlier designs, as Mařák passed away in 1899. His original contributions were made in the late 19th century.

His works were exhibited in Prague, Vienna, and other European cities like Berlin and Leipzig, gaining him contemporary recognition. Many of his paintings are now held in the collections of the National Gallery Prague and other Czech museums.

Graphic Arts and Illustrations

Beyond his celebrated oil paintings, Julius Mařák was a highly accomplished draughtsman and graphic artist. He produced numerous drawings, etchings, and illustrations for books and periodicals. His graphic work often mirrored the themes of his paintings, with a particular focus on forest landscapes and natural details. These works showcase his precise line work and his ability to create rich tonal variations and atmospheric effects in monochrome.

His skill in illustration was significant, and he contributed to various publications, bringing visual life to literary texts. The mention of him inventing a "unique technique" likely pertains to his graphic processes or his innovative approach to composition and light within the constraints of print media. This aspect of his career further demonstrates his versatility and his commitment to exploring different artistic avenues for expressing his vision of nature.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Julius Mařák passed away in Prague on October 8, 1899. His death was marked by a commemorative exhibition in 1900, and another significant exhibition was held in 1999 to mark the centenary of his passing, showcasing even some of his lesser-known works.

His most immediate and tangible legacy lies in the "Mařák School" and the profound impact he had on his students. Through them, his emphasis on direct observation, plein-air painting, and the emotional interpretation of landscape was transmitted and transformed, feeding into the development of Czech Impressionism and early modernism. Artists like Antonín Slavíček, while forging their own distinct paths, acknowledged their debt to Mařák's guidance.

Historically, Mařák is considered a key figure in the Czech Romantic landscape tradition, bridging the gap between earlier, more idealized forms of landscape painting and the more subjective, impressionistic approaches that followed. He played a crucial role in establishing landscape painting as a significant and respected genre within Czech art.

However, as with many artists, critical perspectives can evolve. Some later 20th-century and contemporary art historians have occasionally viewed his work as perhaps overly romanticized or sentimental, particularly when assessed against the backdrop of emerging modernist concerns or specific interpretations of Czech national identity in art. There have been discussions, for instance, where his work was seen as less directly engaged with the "historical truth" of the Czech nation's formation compared to other contemporaries who might have focused on historical or genre scenes with more explicit national narratives.

Despite such critical nuances, Mařák's artistic achievements remain undeniable. His ability to capture the poetic essence of the Bohemian landscape, particularly its forests, is unparalleled. He instilled a deep love for the native landscape in his students and the broader public. His paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, their atmospheric depth, and their heartfelt connection to the natural world. He remains a beloved figure in Czech art history, a master whose canvases invite viewers to step into the tranquil and often mystical realm of the forest. His influence extended beyond his immediate students, contributing to a broader appreciation for landscape art in Bohemia and shaping the visual identity of the Czech lands.