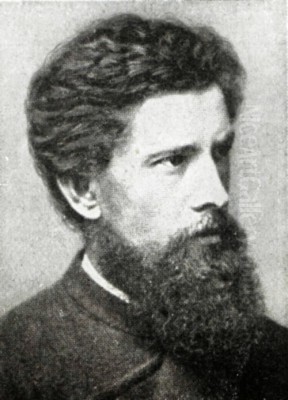

Karl Buchholz (1849-1889) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes tragically overlooked, figure in the annals of 19th-century German art. A pivotal painter associated with the Weimar Saxon-Grand Ducal Art School, commonly known as the Weimar School, Buchholz carved a distinct niche for himself through his evocative and atmospheric landscape paintings. His work, characterized by a subtle palette, meticulous observation, and a profound connection to the German countryside, offers a unique window into the artistic currents of his time, bridging late Romantic sensibilities with the burgeoning impulses of Impressionism. Though his life was cut short, his artistic contributions and influence on subsequent artists affirm his place in German art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in 1849, Karl Buchholz emerged during a period of significant cultural and political transformation in the German states. His formative years coincided with a growing appreciation for regional identity and the natural landscape, themes that would become central to his artistic oeuvre. While specific details about his earliest artistic inclinations are not extensively documented, his path inevitably led him to Weimar, a city renowned as a crucible of German Classicism and, by the mid-19th century, a burgeoning center for innovative art education.

The Weimar Saxon-Grand Ducal Art School, founded in 1860, quickly became a magnet for aspiring artists. It was here that Buchholz would hone his skills and develop his characteristic style. The school's ethos, particularly under the influence of painters who emphasized direct observation of nature, provided fertile ground for Buchholz's talents to flourish.

The Weimar School and Buchholz's Artistic Milieu

The Weimar School was not a monolithic entity but rather an environment that fostered various artistic tendencies. It initially had strong links to late Romanticism and history painting, but by the time Buchholz was active, a significant shift towards landscape painting and a more naturalistic approach was well underway. This movement, often referred to as "intimate landscape" or Stimmungsimpressionismus (atmospheric Impressionism), sought to capture the mood and specific light conditions of a scene, rather than purely topographical accuracy or grand allegorical statements.

Within this context, Buchholz found his voice. He was particularly drawn to the unspectacular, often melancholic beauty of the Thuringian countryside surrounding Weimar. His contemporaries at the school and in the broader German art scene included figures who were similarly exploring new avenues in landscape art. The influence of his teacher, Theodor Hagen (1842-1919), a prominent landscape painter and professor at the Weimar Art School from 1871, was crucial. Hagen himself was influenced by French plein-air painting and encouraged his students to study nature directly.

Artistic Style: Subtlety, Atmosphere, and a Restrained Palette

Karl Buchholz's artistic style is distinguished by its profound sensitivity to the nuances of light, atmosphere, and the subtle poetry of the natural world. He was a master of capturing the quiet, often melancholic moods of the German landscape, particularly the forests, fields, and riverbanks around Weimar. His approach was deeply rooted in the principles of Freilichtmalerei, or open-air painting, although, like many of his contemporaries, he would often complete his works in the studio based on meticulous outdoor sketches and studies.

A hallmark of Buchholz's technique was his restrained and carefully modulated color palette. He eschewed vibrant, ostentatious hues in favor of subtle gradations of greens, browns, grays, and blues, which perfectly conveyed the often-overcast skies and diffused light of the Thuringian region. This limited chromatic range, far from being a constraint, became a strength, allowing him to focus on tonal harmonies and the delicate interplay of light and shadow. His paintings often possess a quiet, introspective quality, inviting contemplation rather than immediate spectacle.

The influence of the French Barbizon School is discernible in Buchholz's work, particularly in his commitment to depicting nature with honesty and a sense of lived experience. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny had pioneered a more direct and unpretentious approach to landscape, and their ethos resonated across Europe. Buchholz, however, adapted these influences to his own German context, imbuing his scenes with a distinctly Northern European sensibility. His work is sometimes considered an early form of German Impressionism, focusing on the subjective experience of nature and the fleeting effects of light, though it retained a stronger connection to drawing and structure than some of its French counterparts.

Buchholz paid meticulous attention to detail, but not in a photographic or hyperrealistic sense. Instead, his details served to enhance the overall atmospheric effect and tactile quality of his paintings. He often primed his canvases and then built up his compositions with careful brushwork, sometimes employing techniques like spackling to create texture, particularly in the rendering of foliage or earthy terrains. This focus on the material quality of paint and surface contributed to the intimate and immersive experience of his landscapes.

Key Themes and Subjects: The Soul of the German Landscape

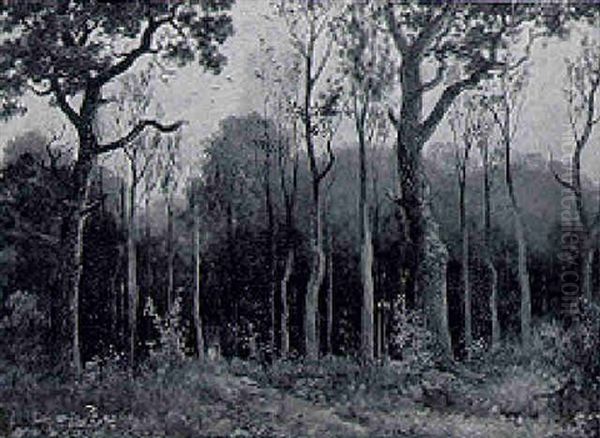

The primary subject matter for Karl Buchholz was the German landscape, particularly the environs of Weimar. He was drawn to the unadorned, everyday aspects of nature: quiet forest interiors, winding country paths, the gentle flow of rivers, and the changing seasons. His paintings rarely feature dramatic mountain vistas or overtly romanticized scenes. Instead, he found beauty in the commonplace, in the subtle shifts of light through trees, the reflection of the sky in water, or the stark silhouettes of trees in winter.

Forest scenes are particularly prominent in his oeuvre. Buchholz had a remarkable ability to convey the dense, enclosing atmosphere of a woodland, the play of sunlight filtering through leaves, and the intricate textures of bark and undergrowth. These were not just depictions of trees, but explorations of the forest as a space of solitude, mystery, and quiet majesty.

The changing seasons provided another rich vein of inspiration. He captured the fresh greens of spring, the hazy light of summer, the russet tones of autumn, and the stark, monochromatic beauty of winter with equal acuity. Each season offered a different palette and a different mood, allowing him to explore the cyclical rhythms of nature and their emotional resonance. His landscapes often evoke a sense of stillness and introspection, reflecting a deep, personal connection to the natural world. While human figures are rare in his paintings, their absence often amplifies the sense of nature's quiet self-sufficiency.

Representative Works: Glimpses into Buchholz's Vision

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be elusive, several works are frequently cited as representative of Karl Buchholz's artistic vision and skill. These paintings exemplify his characteristic style and thematic concerns.

"Autumn Forest" (Herbstwald) and "Winter Woodland Path" (Winterlicher Waldweg) are quintessential Buchholz landscapes. These titles themselves suggest his preoccupation with seasonal changes and forest interiors. In such works, one can expect to see his mastery of subdued color, his ability to render the textures of nature, and his skill in capturing a specific atmospheric mood – be it the melancholic beauty of autumn or the crisp stillness of winter.

Works exhibited during his lifetime, such as "Waldwege" (Forest Paths) and "Dorfwiege" (Village Cradle/Paths), further underscore his focus on the local Thuringian landscape. "Waldwege" likely depicted the intimate, often shadowed paths that wind through the region's forests, a recurring motif in his art. The title "Dorfwiege" is slightly more ambiguous; "Wiege" means cradle, suggesting perhaps a metaphorical depiction of a village nestled in the landscape, or it could be a slight variation or mistranscription of "Dorfwege" (village paths), which would align more closely with his typical subject matter. Regardless of the precise interpretation, such titles point to his deep engagement with the rural environment.

His paintings are often described as elegant and possessing a soft tonality. They are noted for their adherence to tradition in terms of careful composition and drawing, yet they also exhibit a unique personal style in their interpretation of light and atmosphere. Unlike some of the more emotionally overt expressions of French Impressionism, Buchholz's work often conveyed a deeper, more spiritual or contemplative engagement with nature, emphasizing its quiet, mysterious, and sometimes stark aspects, rather than a purely romanticized or picturesque view.

Exhibitions and Recognition: A Career Gaining Momentum

Karl Buchholz's talent did not go unnoticed during his lifetime. He actively participated in the art world, exhibiting his works in significant national and international venues. These exhibitions played a crucial role in establishing his reputation and bringing his unique vision of the German landscape to a wider audience.

His participation in the 1878 Paris World's Fair (Exposition Universelle) was a notable achievement, placing his work on an international stage alongside artists from across the globe. This was followed by an exhibition at the 1879 Munich International Art Exhibition, another prestigious event that showcased contemporary artistic trends. Such international exposure was vital for German artists seeking recognition beyond their national borders.

In Germany, Buchholz's works were regularly featured in important exhibitions. A particularly significant moment came with the 1905 Berlin Art Exhibition. This event, which included a special section dedicated to German landscape painters of the 19th century, featured sixteen of Buchholz's paintings. This marked a posthumous breakthrough in the broader appreciation of his work, highlighting his contribution to the genre.

The following year, in 1906, the Berlin National Gallery's Centennial Exhibition included eleven of Buchholz's pieces. The inclusion of his paintings in such a prominent institutional exhibition further solidified his standing and ensured that his art would be seen and studied by a new generation. Earlier, a retrospective covering works from 1856-1886 (though the start date seems too early for Buchholz's mature work, it might refer to a broader school retrospective) saw his contributions praised for their elegant tonality and masterful depiction of light and atmospheric phenomena. These accolades, especially those received posthumously, underscore the enduring quality of his art.

Teaching and Influence: Shaping Future Generations

Beyond his personal artistic output, Karl Buchholz also played a role in shaping the next generation of artists, primarily through his association with the Weimar Art School and the influence his work exerted on his peers and younger painters. While he may not have held a formal, long-term professorship in the same vein as Theodor Hagen, his artistic principles and distinctive style resonated with many.

His teacher, Theodor Hagen, was a central figure in Weimar's landscape painting tradition, and Buchholz undoubtedly absorbed much from Hagen's emphasis on direct observation and atmospheric rendering. In turn, Buchholz's own interpretations of these principles influenced others.

Among the artists who acknowledged Buchholz's influence was Paul Baum (1859-1932). Baum, who also studied at the Weimar Art School, went on to become a significant German Impressionist and later a proponent of Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism). He recognized Buchholz as an important early inspiration, particularly in the approach to landscape and the sensitive depiction of light.

Ludwig von Gleichen-Rußwurm (1836-1901), a descendant of Friedrich Schiller and an accomplished Impressionist landscape painter and etcher, was also a student of Buchholz. He dedicated himself fully to painting under Buchholz's guidance, absorbing the nuanced approach to capturing the Thuringian scenery.

Other artists associated with the Weimar circle who felt Buchholz's impact, either directly as students or indirectly through his work, include Eduard Weichberger (1843-1913), who, despite maintaining a certain artistic distance, was undoubtedly aware of and responded to Buchholz's innovations. The painter Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven (1860-1941), also active in Weimar, benefited from Buchholz's artistic concepts. Furthermore, artists like Franz Hoffmann-Fallersleben (1855-1927) and Emil Zschimmer (1842-1917) are noted as having learned from and been inspired by Buchholz's artistic philosophy, even if Buchholz himself was described as a relatively isolated figure. This suggests that his influence was perhaps more pervasive through the quiet power of his work than through overt pedagogical activity.

Contemporary Reception: A Mix of Praise and Critique

The reception of Karl Buchholz's work by his contemporaries—fellow artists, critics, and the public—was complex and varied, reflecting the shifting artistic tastes and critical debates of the late 19th century. While he achieved a degree of recognition and respect, his art also faced its share of criticism.

Positive assessments often highlighted his delicate emotional sensibility and his profound understanding of the German natural landscape. The Berlin art critic Ludwig Pietsch, for instance, praised Buchholz for these qualities, recognizing the authenticity and depth in his depictions. His ability to capture the subtle, often melancholic moods of nature, and his restrained yet evocative use of color, were appreciated by those who valued introspection and sincerity in art. His works were seen by some as possessing a quiet, rigorous, and mysterious character, offering a distinct alternative to the more dramatic or picturesque styles prevalent at the time, and contrasting with the more vibrant palette of French Impressionism.

However, Buchholz's style was not universally lauded. Some critics found his meticulous attention to detail to be at the expense of a broader, more unified vision. For example, critics like Schwedler-Meyer and Emil Heilbut (a notable proponent of Impressionism in Germany) voiced criticisms, suggesting that his work sometimes appeared to be an overly studied imitation of light and shadow effects, possibly lacking in groundbreaking innovation or falling short of the dynamism seen in French Impressionism. They may have perceived his adherence to certain traditional compositional principles or his subdued palette as conservative, especially when compared to the more radical experiments happening elsewhere in Europe.

Art critic Franz Dülberg, in an exhibition review, noted that Buchholz's painting style seemed to emerge directly from the qualities of the oil paint itself, emphasizing his strong understanding of air and light. Another significant art historian, Richard Hamann, lauded Buchholz's landscape "Land in 1876," praising its truthful depiction of nature and its atmospheric depth. Gustav Floerke, associated with the Weimar Kunsthalle, also likely contributed to the discourse surrounding Buchholz and the Weimar School, though specific evaluations are not detailed in the provided snippets.

Despite the critiques, Buchholz's works were acquired by museums and private collectors, indicating a tangible appreciation for his artistic merit. His frequent participation in major exhibitions also attests to a level of peer recognition within the art establishment of his time.

Later Years and Tragic End

Despite his artistic achievements and growing recognition, Karl Buchholz's later years were reportedly marked by a sense of being overlooked or neglected by the art world. This perception, whether entirely accurate or a reflection of personal struggles, casts a somber shadow over the end of his life. In 1889, at the age of just forty, Karl Buchholz tragically died by suicide.

The reasons behind such a desperate act are often complex and multifaceted, and it is difficult to speculate with certainty. However, the pressures of an artistic career, the fluctuating tastes of the public and critics, financial insecurities, and personal temperament can all contribute to an artist's vulnerability. If he indeed felt his work was not receiving the attention it deserved, this could have exacerbated any underlying personal difficulties. His early death cut short a career that was still evolving and deprived the German art world of a unique and sensitive voice.

Posthumous Reassessment and Enduring Legacy

Following his untimely death, Karl Buchholz's work gradually underwent a period of reassessment. While he may have felt underappreciated in his final years, the posthumous exhibitions, particularly the significant showings in Berlin in 1905 and 1906, played a crucial role in re-establishing his reputation and securing his place as an important representative of the Weimar School and a key figure in late 19th-century German landscape painting.

His art is valued for its sincere and introspective engagement with nature, its masterful handling of light and atmosphere, and its unique blend of observational accuracy and poetic sensibility. He is recognized as one of the artists who helped to define a distinctly German approach to landscape painting in an era that was increasingly looking towards French Impressionism. Buchholz demonstrated that a profound and modern artistic statement could be made through a deep connection to one's own regional environment, rendered with subtlety and technical finesse.

His influence on students and fellow artists, such as Paul Baum and Ludwig von Gleichen-Rußwurm, also forms part of his legacy, as these artists carried forward and adapted the principles they had absorbed, contributing to the ongoing development of German art. Today, Karl Buchholz's paintings are held in various public and private collections, and he is studied as an important link in the chain of German landscape tradition, a painter who captured the soul of the Thuringian countryside with quiet conviction and enduring artistry.

A Note on a Different Karl Buchholz: The 20th-Century Art Dealer

It is important to note, for clarity, that the art historical record includes another prominent Karl Buchholz, an art dealer active in the 20th century, particularly during the tumultuous Nazi era in Germany. This Karl Buchholz (whose lifespan differs from the painter's 1849-1889) operated a gallery in Berlin and became controversially involved in the sale of "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst)—modern artworks confiscated by the Nazi regime from German museums and Jewish collectors.

This art dealer Karl Buchholz was one of four dealers authorized by the Nazi government to sell these confiscated works abroad, ostensibly to bring foreign currency into Germany. He collaborated with figures like Hildebrand Gurlitt, Ferdinand Möller, and Bernhard A. Böhmer. A key associate was Curt Valentin, who had worked for Buchholz in Berlin before emigrating to New York, where he established the Buchholz Gallery Curt Valentin. Many "degenerate" works by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian (whose "Composition with Blue" passed through these channels), Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, George Grosz, Otto Dix, Marc Chagall, and sculptors like Gerhard Marcks and Renée Sintenis were sold or transferred through this network. His competitors in this fraught market included dealers like Karl Nierendorf and Otto Kallir (founder of Galerie St. Etienne).

The activities of this Karl Buchholz, the art dealer, are a subject of ongoing provenance research and debate concerning the restitution of Nazi-looted art. His story is one of complex moral and ethical dimensions, intertwined with the tragic fate of modern art under the Third Reich. It is crucial to distinguish this 20th-century art dealer from Karl Buchholz (1849-1889), the Weimar School landscape painter, to avoid historical confusion, as their lives, careers, and legacies are entirely separate, though the shared name can sometimes lead to conflation in less precise accounts.

Conclusion: The Quiet Power of Karl Buchholz the Painter

Karl Buchholz, the painter of the Weimar School, remains a compelling figure whose art speaks with a quiet yet profound eloquence. His dedication to capturing the essence of the German landscape, his subtle mastery of color and light, and his ability to evoke deep atmospheric moods set him apart. Though his life was tragically brief, his paintings offer a lasting testament to his unique vision. He navigated the artistic currents of his time, drawing from tradition while forging a personal style that contributed significantly to the rich tapestry of 19th-century German art. His work continues to resonate with those who appreciate the beauty of understated expression and the deep, contemplative connection between an artist and the natural world.