Herman van Swanevelt stands as a significant figure in the Dutch Golden Age of painting, a master of the landscape genre whose career bridged the artistic worlds of the Netherlands, Italy, and France during the vibrant Baroque era. Born around 1603 in the Dutch town of Woerden, he emerged from an environment steeped in artistic tradition; his lineage reportedly included the renowned earlier Netherlandish painter and printmaker, Lucas van Leyden. Swanevelt's own contributions, particularly his development of the idyllic Italianate landscape and his mastery of etching, secured his place in art history and influenced subsequent generations of artists. His life was marked by extensive travel, prestigious commissions, and a deep engagement with the natural world, earning him recognition across Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Details surrounding Herman van Swanevelt's earliest training remain somewhat obscure. While concrete evidence is lacking, modern scholarship has proposed that he might have studied under Willem Buytewech, a prominent painter and etcher known for his genre scenes and landscapes in the early 17th century Netherlands. This connection, though hypothetical, suggests a potential early grounding in the Dutch artistic traditions before Swanevelt embarked on the international journey that would define his career. His family background, with ties to an established artist like Lucas van Leyden, likely provided an encouraging atmosphere for pursuing an artistic path.

The first tangible evidence of Swanevelt's independent artistic activity dates to 1623, when he signed two landscape paintings depicting scenes of Paris. This indicates that his early career may have involved a period in the French capital before his pivotal move southward. These initial works already hinted at his burgeoning interest in landscape, a genre he would explore and refine throughout his life. His presence in Paris at this early stage foreshadows the significant role France would later play in his career, following his formative years in Italy.

The Roman Sojourn: Influence and Innovation

In 1629, Herman van Swanevelt relocated to Rome, the magnetic center of the European art world during the Baroque period. This move proved decisive for his artistic development. Rome offered a wealth of inspiration: the ruins of antiquity, the sun-drenched Italian countryside (the Campagna), and a vibrant community of international artists. Swanevelt quickly established himself as a successful landscape painter, immersing himself in the city's artistic milieu and the surrounding natural environment.

His time in Rome was characterized by intense observation and sketching. Swanevelt developed a reputation for venturing into the countryside surrounding Rome, meticulously studying the effects of natural light, the forms of ancient ruins, and the textures of the landscape. This dedicated, solitary approach to studying nature earned him the nickname "Heremiet" (the Hermit) among his peers. This practice of direct observation from nature was crucial in shaping his distinctive style, lending authenticity and atmospheric depth to his painted and etched views.

During his Roman years, Swanevelt became closely associated with several key figures who were shaping the direction of landscape painting. Most notably, he developed a close relationship with the French painter Claude Lorrain, who would become one of the most celebrated landscape artists of the era. Sources suggest that for a period, likely between 1628 and 1630 (overlapping Swanevelt's arrival), the two artists may have even shared lodgings. This proximity fostered significant artistic exchange, although the precise nature of their mutual influence remains a subject of discussion among art historians.

While undeniably influenced by Claude, particularly in the development of idealized, light-filled landscapes, Swanevelt's style retained its own distinct characteristics. Some scholars argue that Swanevelt pioneered certain aspects of the idyllic landscape, such as the sophisticated rendering of sunlight effects at different times of day, even before Claude fully developed these elements in his own work. Swanevelt's approach often featured a slightly cooler palette and perhaps a more detailed rendering of foliage compared to Claude's broader, more atmospheric effects.

Swanevelt's Roman environment also brought him into contact with other influential landscape traditions and artists. He absorbed the lessons of the earlier generation of Northern artists working in Rome, such as the Flemish painter Paul Bril, who had already established a tradition of depicting Italian scenery. He was also part of the circle of Dutch and Flemish artists known as the "Bentvueghels" (Birds of a Feather), a confraternity known for its bohemian activities but also for fostering artistic exchange.

Furthermore, Swanevelt's work shows an affinity with the styles of other Dutch Italianate painters active in Rome during the same period, such as Cornelis van Poelenburgh and Bartholomeus Breenbergh. These artists specialized in smaller-scale landscapes often featuring mythological or biblical figures set against Italianate backgrounds, frequently incorporating classical ruins. Swanevelt integrated elements of their detailed approach and subject matter into his larger, more expansive landscape conceptions, creating a unique synthesis of Northern precision and Italianate breadth. His interactions extended to figures like Giles de Houtman and Frans van de Stael, further embedding him within the network of Northern artists active in the city. The towering figure of Nicolas Poussin, another French artist perfecting the classical landscape in Rome, also formed part of this rich artistic context, contributing to the overall move towards idealized, structured landscape compositions.

Artistic Style: The Idyllic Landscape

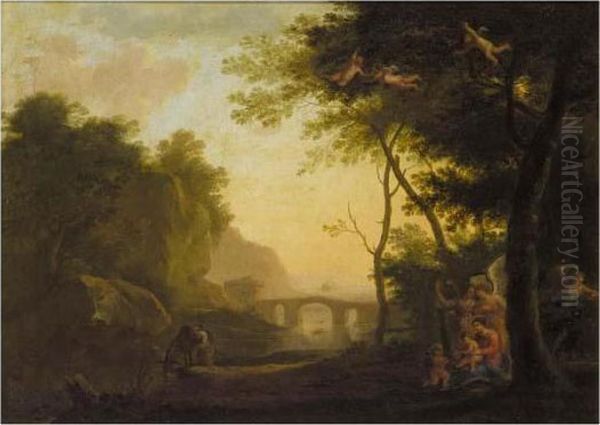

Herman van Swanevelt's signature contribution lies in his development and popularization of the idyllic Italianate landscape. His works typically depict expansive views of the Roman Campagna or imagined pastoral settings, bathed in warm, atmospheric light. He was among the first generation of artists to focus intently on capturing the specific qualities of Mediterranean light, often structuring his compositions around the effects of the rising or setting sun. This innovative use of light, creating what was described as "sunlit backgrounds," became a hallmark of his style and profoundly influenced the course of European landscape painting.

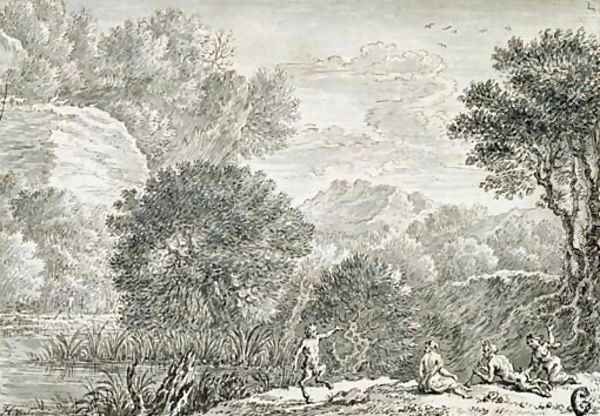

His landscapes are carefully constructed, balancing naturalistic observation with idealized harmony. Trees often frame the composition, leading the viewer's eye into receding planes of hills, valleys, and distant mountains. Architectural elements, such as classical ruins, bridges, or pastoral dwellings, are frequently integrated into the scenery, adding historical resonance or narrative context. While nature dominates, human presence is often included in the form of small figures – shepherds, travelers, mythological characters, or biblical figures – which serve to animate the scene and establish its theme, but rarely overwhelm the grandeur of the landscape itself.

Swanevelt frequently incorporated biblical and mythological narratives into his landscapes, a common practice in the Baroque era. Works depicting stories like the Rest on the Flight into Egypt or scenes involving nymphs and satyrs allowed him to combine his skill in landscape with the elevated subject matter favored by patrons. However, the landscape itself always remained a primary focus, imbued with a sense of tranquility and timelessness. His paintings often evoke a mood of serene contemplation, reflecting an idealized vision of nature in harmony with history and myth.

Compared to some of his contemporaries, Swanevelt's palette often employed cooler tones, particularly in his greens and blues, balanced by the warm golden light that suffuses his skies and highlights elements within the scene. His brushwork could be detailed, especially in the rendering of foliage and foreground elements, reflecting his Northern European roots, yet he also achieved broad atmospheric effects in his depiction of distance and sky, demonstrating his mastery of Italianate techniques. This fusion of detailed observation and idealized composition became characteristic of the Dutch Italianate style, of which Swanevelt was a leading exponent.

Mastery in Etching

Beyond his significant achievements as a painter, Herman van Swanevelt was also a prolific and highly accomplished etcher. Printmaking offered a different medium for exploring his fascination with landscape and allowed his work to reach a wider audience. His etchings are celebrated for their technical finesse, intricate detail, and sophisticated handling of light and shadow, mirroring the atmospheric qualities of his paintings.

His etched oeuvre consists of numerous series, primarily depicting landscapes, Roman ruins, and biblical or mythological scenes set in nature. He produced detailed views of the Roman countryside, capturing the specific character of the terrain, the vegetation, and the ancient monuments that dotted the landscape. Series depicting famous Roman landmarks, such as the View of the Porta San Paolo and the Pyramid of Cestius or the View of the Arch of Constantine, showcase his keen eye for architectural detail and his ability to integrate these structures harmoniously within a natural setting.

Swanevelt's etchings often explore narrative themes similar to those in his paintings. His series on the Rest on the Flight into Egypt is a notable example, where the Holy Family is depicted in various serene landscape settings. Another significant series features penitent saints in the wilderness, such as The Magdalen Repentant, demonstrating his ability to convey spiritual themes through the evocative power of landscape. These works highlight his skill in using the linear medium of etching to create rich textures, varied tones, and a compelling sense of depth and atmosphere.

The technical quality of his prints was exceptional. He employed fine, controlled lines and delicate cross-hatching to model forms and suggest the play of light across surfaces. His ability to render the textures of foliage, rocks, water, and clouds in the demanding medium of etching was widely admired. Swanevelt's prints were highly sought after during his lifetime and continued to be influential, serving as models for later generations of landscape etchers. His contributions solidified his reputation not only as a painter but also as one of the foremost Dutch printmakers of his time.

Patronage and Recognition Across Europe

During his years in Rome, Swanevelt's talent attracted prestigious patronage. He received commissions from influential figures within the Church and aristocracy. Notably, he worked for the powerful Barberini family, the family of Pope Urban VIII. He also received commissions directly from Pope Urban VIII himself, a testament to his high standing in the Roman art world. His reputation extended beyond Italy, reaching the Spanish court; King Philip IV of Spain commissioned works from him, likely for the decoration of the Buen Retiro Palace in Madrid, a major project that involved many leading artists of the day.

This high-level patronage underscores the appeal of Swanevelt's art. His idealized landscapes, infused with classical or biblical themes and rendered with technical skill and atmospheric beauty, resonated with the tastes of the European elite. His ability to blend Northern European detail with the grandeur and light of the Italian tradition made his work desirable across national borders.

After more than a decade in Rome, Swanevelt returned to Paris around 1641. His reputation preceded him, and he quickly found favor in the French capital. He received commissions from prominent figures such as Cardinal Richelieu, the powerful chief minister to King Louis XIII. Following Richelieu's death, Swanevelt continued to enjoy royal patronage, working for King Louis XIV. His success in France culminated in his appointment as a Painter in Ordinary to the King (Peintre ordinaire du Roi) and his admission to the prestigious Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) in 1651. This official recognition cemented his status within the French art establishment. His work during this period, such as The Birth of Apollo, reflects his continued engagement with mythological themes within grand landscape settings, adapted perhaps to suit French tastes.

Later Life, Legacy, and Representative Works

Herman van Swanevelt spent the latter part of his career primarily in Paris, where he remained an active and respected member of the artistic community until his death in 1655. While one of the provided snippets mentions a possible return to his hometown of Woerden in later life, the consensus among art historians is that he died in Paris. His presence in the records of the Royal Academy supports his continued activity in the French capital.

Swanevelt's influence extended significantly beyond his own lifetime. His development of the idyllic landscape, characterized by its harmonious composition, atmospheric light, and integration of narrative elements, had a lasting impact on the genre. He served as a crucial link between the early pioneers of Italianate landscape (like Bril and Poelenburgh) and the later generations of Dutch Italianate painters, such as Nicolaes Berchem, who clearly absorbed lessons from Swanevelt's approach to light and composition. His work also influenced landscape painting in France and England throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

His paintings and etchings found their way into important collections across Europe. Today, his works are held by major museums worldwide, including the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Louvre in Paris, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the British Museum in London, among many others. These collections preserve a rich body of work that showcases his versatility as both a painter and a printmaker.

Among his many notable works, several stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns:

Old Testament Scene: An early Roman work exemplifying his classical landscape composition and handling of light.

Wooded Landscape (Getty Museum): A quintessential example of his mature idyllic style, showcasing lush foliage and atmospheric depth.

Landscape with Bathing Nymphs: Demonstrates his integration of mythological figures into idealized natural settings.

Travelers and the Huntsman: Highlights his skill in depicting expansive landscapes animated by small figures engaged in everyday or pastoral activities.

The Magdalen Repentant (etching): A key example from his series of penitent saints, showcasing his mastery of the etching medium for expressive landscape and narrative.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt (etching series): Demonstrates his recurring interest in biblical themes set within serene, detailed landscapes.

View of the Porta San Paolo and the Pyramid of Cestius: Reflects his careful observation and artistic interpretation of Roman antiquities within their landscape context.

Waterfall with Fishermen: Showcases his ability to capture the dynamism of nature alongside tranquil human activity.

The Birth of Apollo: Likely from his French period, representing his work for high-level patrons involving mythological subjects.

View of the Arch of Constantine (Vue de l'Arche de Constantin): Another example of his detailed depictions of Roman monuments, popular both as paintings and etchings.

Conclusion

Herman van Swanevelt was a pivotal figure in 17th-century European landscape art. Emerging from the Netherlands, he absorbed the crucial influences of the Roman artistic environment, forging a distinctive style characterized by idealized beauty, atmospheric light, and a harmonious blend of nature and narrative. His close association, yet artistic independence, from Claude Lorrain highlights his unique position in the development of the classical landscape. As both a painter and a highly skilled etcher, Swanevelt enjoyed international patronage and left a significant legacy, influencing artists in the Netherlands, France, and beyond. His tranquil, light-filled visions of the Italian countryside continue to be admired for their technical brilliance and evocative power, securing his place as a true master of the Baroque landscape.