Nathaniel Hone the Elder stands as a significant, albeit sometimes controversial, figure in the landscape of 18th-century British and Irish art. Born in Dublin and forging a successful career primarily in London, Hone was a versatile artist, renowned for his portraits, particularly miniatures and works in enamel. His role as a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts places him at the heart of the institutionalisation of art in Britain, yet his independent spirit and satirical inclinations often set him at odds with the very establishment he helped create. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the bustling, competitive, and evolving art world of Georgian London.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Nathaniel Hone was born in Dublin, Ireland, on April 24, 1718. His father, also named Nathaniel Hone, was a merchant of Dutch descent who had settled in Dublin. The Hone family was part of the city's prosperous Protestant community. Details about young Nathaniel's earliest artistic training remain somewhat obscure, but it is clear that he demonstrated talent from a young age. Like many aspiring artists of the period without formal academy access in their youth, he likely began by copying prints and perhaps received rudimentary instruction locally.

His early career path followed a pattern common for portraitists seeking to build a reputation and clientele: that of an itinerant painter. Hone travelled through England, working in various towns and cities, honing his skills by fulfilling commissions for portraits, likely often in the form of miniatures. Miniature painting, requiring meticulous detail and a steady hand, was a highly valued skill, providing portable and intimate likenesses for patrons. This period of travel was crucial for developing both his technical proficiency and his understanding of the market for portraiture.

A pivotal moment in his personal and professional life occurred in 1742 when he married Mary Earle. Sources often describe Mary as the natural daughter of John Campbell, 4th Duke of Argyll, a powerful Scottish nobleman. While the exact nature of her parentage is sometimes debated, the connection, or perceived connection, to aristocracy likely did no harm to Hone's burgeoning career. The marriage provided stability, and shortly thereafter, the couple settled permanently in London, the epicentre of the British art world, where Hone sought to establish himself amongst the leading painters of the day.

Italian Sojourn and Stylistic Development

Seeking to further refine his art and enhance his reputation, Hone undertook a period of study in Italy, travelling there around 1750 and remaining for approximately two years. Italy, particularly Rome, was considered the ultimate finishing school for ambitious Northern European artists. Exposure to the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods was deemed essential for anyone aspiring to practice 'history painting', the most highly regarded genre, but it also profoundly influenced portraitists.

During his time in Italy, Hone is known to have spent time in Rome and Florence. In Florence, he reportedly enrolled in the Accademia del Disegno, one of the oldest art academies in Europe. This experience would have involved life drawing and studying the works of Italian masters. Direct engagement with the works of artists like Raphael, Titian, Correggio, and others, as well as the study of antique sculpture, undoubtedly broadened his artistic horizons.

The Italian trip influenced Hone's style, though he never fully adopted the 'Grand Manner' popularised by contemporaries like Sir Joshua Reynolds. Instead, Hone integrated elements of Italian composition and perhaps a richer palette into his existing style, which retained a strong element of direct observation, sometimes bordering on unflattering realism, likely rooted in his Dutch heritage and early miniature work. He developed a particular skill in enamel painting, a demanding technique involving firing pigments onto metal or porcelain, which he likely refined during or after his Italian studies.

Establishing a London Career

Upon returning to London around 1752, Hone set about consolidating his position in the city's competitive art market. He established a studio and quickly gained recognition for his portraits, both full-scale oils and the miniatures and enamels at which he excelled. His works from this period show increasing confidence and sophistication. He attracted a respectable clientele, drawn from the gentry, the professional classes, and notable figures of the day.

His skill as a miniaturist remained a cornerstone of his practice. Miniatures were highly fashionable, serving as keepsakes, love tokens, and diplomatic gifts. Hone's miniatures are noted for their fine detail, psychological acuity, and often vibrant colouring. He also became one of the foremost enamel painters in England. Enamels offered permanence and a jewel-like brilliance distinct from watercolour on ivory (the typical miniature medium) or oil on canvas. This technical expertise set him apart from many competitors.

Hone began exhibiting his work publicly, initially with the Society of Artists, an important precursor to the Royal Academy. His submission of The Brickdust Man in 1760 marked his public debut in the London exhibition scene. He continued to exhibit regularly, building his reputation and attracting commissions. His style, often characterised by a certain Rococo elegance combined with sharp characterisation, found favour with patrons who perhaps sought something less idealised than the portraits offered by Reynolds, yet more refined than the sometimes stark realism of others. He competed for commissions alongside prominent figures like Thomas Gainsborough, Allan Ramsay, and Francis Cotes.

Founding the Royal Academy of Arts

The London art world in the mid-18th century was marked by factionalism and the desire among leading artists for greater professional status and control over training and exhibition standards. Dissatisfaction with the management of the Society of Artists and the Incorporated Society of Artists led a group of prominent figures to petition King George III for the establishment of a Royal Academy. Nathaniel Hone was among the key proponents and became one of the 36 Foundation Members when the Royal Academy of Arts was established by Royal Charter in 1768.

His inclusion signifies his standing among the leading artists in London at the time. The founding Academicians included the most celebrated names: Sir Joshua Reynolds, who was elected its first President, Thomas Gainsborough, the Swiss-born Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser (the only two female founders), the American Benjamin West (who would succeed Reynolds as President), Richard Wilson, the landscape painter, and fellow miniaturist Jeremiah Meyer. Hone's presence in this elite group underscores his reputation, particularly in portraiture and enamel work.

Membership in the Academy offered prestige, exhibition opportunities at the prestigious Annual Exhibition, and a role in shaping the future of British art through the Academy's schools. Hone exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from its inception until his death, submitting portraits, miniatures, and occasional subject pictures. However, his relationship with the institution, and particularly with its powerful President, Reynolds, would prove to be complex and, at times, openly antagonistic.

Artistic Style and Technique

Nathaniel Hone's artistic style is multifaceted, reflecting his Irish roots, Dutch heritage, Italian studies, and engagement with the London art scene. He was fundamentally a portraitist, adept at capturing a likeness, but his approach varied. While capable of producing elegant and fashionable portraits in the Rococo vein, his work often possesses a directness and a psychological penetration that distinguishes it from the more generalised or idealised approach of Reynolds's Grand Manner.

His handling of paint could be precise and detailed, especially in fabrics and accessories, reflecting his training as a miniaturist. Faces are often rendered with careful attention to individual features and expression, sometimes revealing character with an honesty that might not have always flattered the sitter. This contrasts with the smoother, more generalised flesh tones often favoured by Reynolds or the feathery brushwork of Gainsborough.

His skill in miniature painting on ivory and particularly in enamel was exceptional. Enamel work was technically challenging, requiring multiple firings and a deep understanding of how colours would change in the kiln. Hone mastered this medium, producing durable, luminous portraits that rivalled those of continental specialists like Jean-Étienne Liotard (though Liotard worked more often in pastel and oil). His enamels often replicated his larger oil portraits or depicted sitters independently.

While primarily a portraitist, Hone occasionally painted 'fancy pictures' or subject pieces, such as The Spartan Boy (1775). These allowed for greater imaginative scope but remained secondary to his portrait practice. His work shows an awareness of Dutch genre painting in its attention to detail and character, and Italian art in its compositional structures, yet it retains a distinctly British, or perhaps Anglo-Irish, sensibility – pragmatic, observant, and occasionally infused with a dry wit that would later manifest more pointedly in his satirical work.

Notable Works

Throughout his career, Nathaniel Hone produced a substantial body of work. While many portraits were of private individuals whose identities are now obscure, several key works stand out:

The Brickdust Man (c. 1760): Exhibited at the Society of Artists, this character study likely depicted a London street vendor. Such works, showing ordinary working people, were less common than aristocratic portraits but demonstrated an artist's skill in capturing character and realism, perhaps influenced by Dutch genre scenes or the work of earlier British artists like William Hogarth.

Two Gentlemen in Masquerade (1770): Exhibited at the Royal Academy, this painting likely depicted sitters in costumes for a masquerade ball, a popular social event. Such works allowed for playful compositions and the depiction of rich fabrics and accessories, showcasing the artist's versatility.

The Spartan Boy (1775): Also exhibited at the Royal Academy, this subject picture depicted a story from Plutarch illustrating Spartan fortitude. While not a portrait, its exhibition at the RA demonstrated Hone's ambition to engage with historical or moral themes, aligning with Academic ideals, even as he was about to challenge the Academy's leadership.

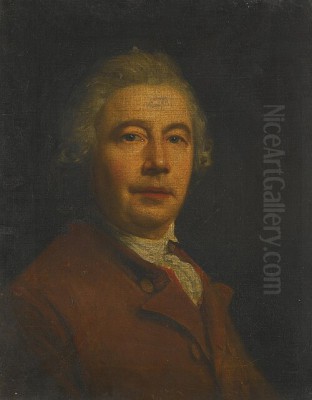

Self-Portraits: Hone painted several self-portraits throughout his career, in oil, miniature, and enamel. These provide valuable insights into his appearance and self-perception. They often show him as a confident, skilled professional, sometimes holding the tools of his trade.

Portrait Miniatures and Enamels: His numerous miniatures and enamels constitute a significant part of his oeuvre. Sitters included members of the aristocracy, gentry, and prominent figures like the Methodist leader John Wesley. These works are highly prized for their technical brilliance and intimate portrayal.

The Conjuror (1775): Undoubtedly his most famous and controversial work, discussed in detail below.

These examples illustrate the range of Hone's output, from formal portraits and intimate miniatures to character studies and subject pictures, reflecting the diverse demands of the 18th-century art market.

The Conjuror Controversy

The most notorious episode in Nathaniel Hone's career revolves around his painting The Conjuror, submitted to the Royal Academy exhibition of 1775. The full title was The Pictorial Conjuror, displaying the whole Art of Optical Deception. The painting depicted an elderly, bearded figure resembling an alchemist or 'conjuror', seated among books and prints, using a magnifying glass. Around him were various objects and images, including reproductions of well-known Old Master paintings.

The work was widely interpreted as a complex satire aimed squarely at Sir Joshua Reynolds, the RA President. Reynolds was known for advocating the study and adaptation of Old Master compositions, a practice Hone seemingly ridiculed as mere 'conjuring' or plagiarism. The prints depicted in the painting allegedly corresponded to works Reynolds had borrowed from. Furthermore, the painting included a nude female figure in the upper corner, which some viewers controversially identified as representing Angelica Kauffman, a fellow Academician rumoured to have a close relationship with Reynolds. This element, whether intended or merely perceived as such, added a layer of personal scandal to the artistic critique.

The RA Council, likely pressured by Reynolds and concerned about the attack on its President and the potentially scandalous reference to Kauffman, rejected the painting. They demanded that Hone alter or remove the offending parts, particularly the nude figure. Hone initially refused but eventually painted it out, replacing it with other elements. However, feeling slighted and censored, he took an unprecedented step.

Hone withdrew The Conjuror and several other works from the RA exhibition. He then rented a room in St. Martin's Lane, opposite the premises of the Incorporated Society of Artists, and mounted his own one-man exhibition. This show, featuring around sixty of his works including the controversial (though altered) Conjuror, is often cited as the first solo retrospective exhibition staged by a living artist in Britain in direct opposition to the established Academy. It was a bold act of defiance, asserting his artistic independence and challenging the authority of the RA Council. The exhibition generated considerable public interest and debate, highlighting the tensions within the London art world.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Nathaniel Hone's career unfolded within a vibrant and highly competitive artistic milieu. His relationship with Sir Joshua Reynolds was clearly one of rivalry, culminating in the Conjuror affair. They represented different facets of the art establishment: Reynolds, the master of the Grand Manner, theorist, and powerful President; Hone, the skilled but independent-minded portraitist and miniaturist, perhaps resentful of Reynolds's dominance and perceived artistic borrowings.

His relationship with Thomas Gainsborough, the other giant of 18th-century British portraiture, seems less documented in terms of direct conflict. Gainsborough himself had a somewhat detached relationship with the Academy later in his career. Both Hone and Gainsborough offered alternatives to Reynolds's style, though Gainsborough's fluid brushwork and emphasis on sensibility differed significantly from Hone's often more precise and detailed approach.

As a fellow founder, Hone would have known Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser well. The alleged reference to Kauffman in The Conjuror suggests a complex dynamic, possibly fueled by professional jealousy or gossip within the art community. Kauffman was a highly successful history painter and portraitist, enjoying royal patronage, which might have made her a target for satire.

Hone also competed with other successful portraitists like George Romney, who became a fashionable rival to Reynolds in the later 1770s and 1780s, and the Scottish painter Allan Ramsay, who held the post of Principal Painter in Ordinary to King George III until his death in 1784. In the field of miniature and enamel painting, his contemporaries and competitors included Richard Cosway, known for his glamorous and flattering miniatures, Ozias Humphry, and fellow RA founder Jeremiah Meyer. Hone's work stands out for its technical solidity and psychological depth compared to the sometimes more flamboyant style of Cosway. He also worked in the shadow of the legacy of William Hogarth, whose satirical prints and 'modern moral subjects' had set a precedent for social commentary in British art.

Later Life and Legacy

Despite the controversy of 1775, Nathaniel Hone continued to practice successfully and exhibit at the Royal Academy until his death. The scandal did not permanently derail his career, suggesting he retained a loyal clientele and a degree of respect within the profession, even if his relationship with the Academy's leadership remained cool. He continued to produce portraits in oil, miniatures, and enamels.

His sons, Horace Hone (1754-1825) and John Camillus Hone (1759-1836), also became artists, particularly known for miniatures, carrying on the family tradition. Horace became an Associate of the Royal Academy and was appointed Miniature Painter to the Prince of Wales.

Nathaniel Hone the Elder died in London on August 14, 1784, at the age of 66. He was buried in Hendon Churchyard. His death occurred in the same year as that of Allan Ramsay, and only a few years before Gainsborough (1788) and Reynolds (1792), marking the passing of a generation that had defined British art in the mid-Georgian period.

Hone's legacy is significant. As a Foundation Member of the Royal Academy, he played a role in establishing the institutional framework for British art that largely persists today. His work as a portraitist, miniaturist, and enamel painter demonstrates high technical skill and keen observation. He provided an alternative stylistic voice to the dominance of Reynolds, maintaining a connection to traditions of realism perhaps rooted in his Dutch ancestry.

His most enduring legacy, however, might be the Conjuror incident and the subsequent one-man show. This act established a precedent for artistic dissent and the use of independent exhibitions as a platform for challenging institutional authority – a strategy employed by later artists throughout history. He remains an important figure for understanding the dynamics of patronage, professional rivalry, and artistic politics in 18th-century London. His works are held in major collections, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and significantly, the National Gallery of Ireland in his native Dublin, which holds a substantial collection of works by him and his descendants.

Conclusion

Nathaniel Hone the Elder was more than just a competent Georgian portraitist. He was a foundational figure in Britain's leading art institution, a master of multiple techniques including the demanding art of enamel, and an artist of independent mind who was unafraid to use his art for pointed satire. His Irish origins and successful London career place him as a key figure in the intertwined art histories of both nations. While perhaps overshadowed in popular renown by Reynolds and Gainsborough, Hone's skill, his significant body of work, and his famous act of defiance against the Academy secure his place as a complex, talented, and historically important artist of the 18th century. His life and art continue to offer rich insights into the personalities, practices, and politics that shaped the British art world during a period of profound transformation.