Mark Gertler stands as a significant yet often complex figure in the landscape of early 20th-century British art. A painter of intense vision and emotional depth, his life and work were inextricably linked to the vibrant, often turbulent, artistic and social currents of his time. Born into poverty in London's East End, he rose through talent and determination to become a prominent member of the British avant-garde, associated with influential groups and individuals. His art, characterized by bold colours, strong forms, and a unique blend of modern European influences and personal experience, continues to resonate. This exploration delves into the life, art, relationships, and enduring legacy of Mark Gertler.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Spitalfields

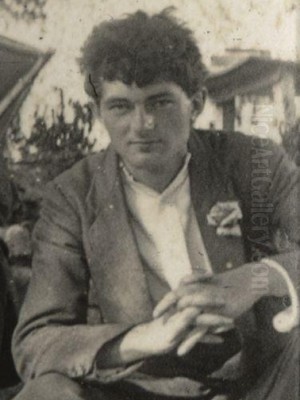

Mark Gertler was born on December 9, 1891, in Spitalfields, London. He was the youngest son of Polish Jewish immigrants, Louis Gertler and Kate (Golda) Berenbaum. His family's circumstances were modest, and the vibrant but often harsh environment of the East End profoundly shaped his early perspective. From a young age, Gertler displayed a remarkable aptitude for drawing, an undeniable talent that set him apart.

Despite his evident promise, financial constraints forced Gertler to leave school early. He briefly worked as an apprentice at Clayton & Bell, a firm specializing in stained glass, a practical application of art but one that failed to satisfy his creative ambitions. His desire to pursue fine art remained strong, fueled by his innate passion and visits to the National Gallery.

Recognizing his potential, the Jewish Educational Aid Society awarded Gertler a crucial scholarship in 1908. This enabled him to enroll at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, a powerhouse of artistic training that was nurturing a generation of exceptional British talent. The years from 1908 to 1912 at the Slade were formative, placing him among a cohort of gifted contemporaries.

The Slade School and the "Whitechapel Boys"

The Slade School provided Gertler with rigorous academic training under influential teachers like Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer. He excelled, winning prizes for his drawing and painting skills, quickly establishing a reputation as one of the most promising students of his generation. His technical proficiency, particularly his draughtsmanship, was widely acknowledged.

During his time at the Slade, Gertler formed connections with a remarkable group of fellow students who would significantly impact British modernism. These included Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer, C.R.W. Nevinson, Edward Wadsworth, and Dora Carrington. He also became associated with the "Whitechapel Boys," a loose group of Anglo-Jewish artists and writers emerging from the East End, including the poet Isaac Rosenberg and the painter David Bomberg. This network provided both camaraderie and intellectual stimulation.

Gertler's early work from this period already showed a distinctive strength and intensity. He absorbed the lessons of the Slade but began to look towards more radical European influences, particularly the Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne, whose work had been showcased in London in Roger Fry's seminal exhibitions of 1910 and 1912. These exhibitions were transformative for many young British artists, including Gertler.

Developing a Unique Style: Influences and Innovation

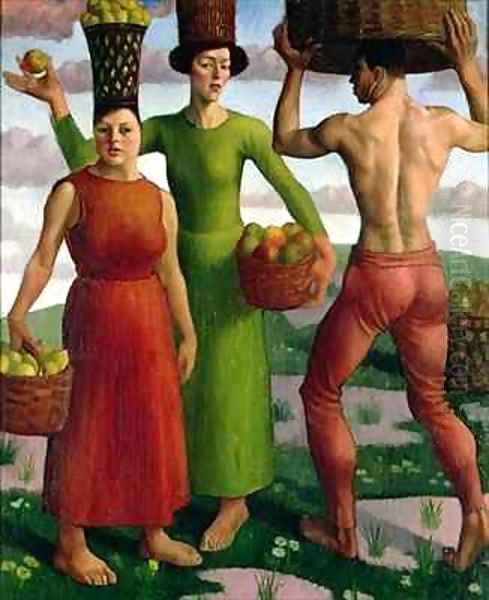

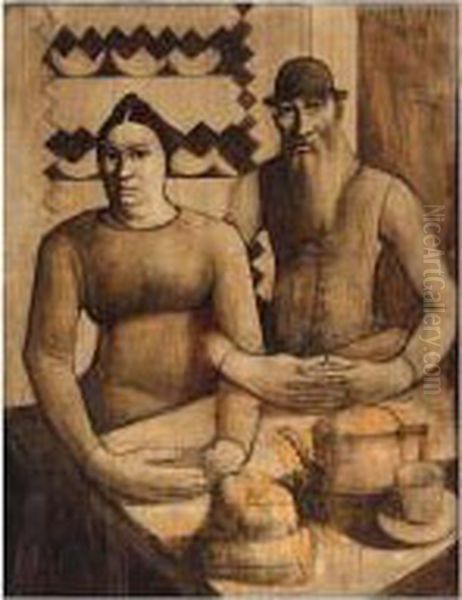

While Post-Impressionism provided a crucial catalyst, Gertler forged a style uniquely his own. He synthesized the structural solidity of Cézanne with the vibrant colour and emotional intensity found in the work of artists like Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse. There was also a discernible influence from Eastern European folk art, likely absorbed from his family background, visible in the decorative patterning and bold, simplified forms found in some works.

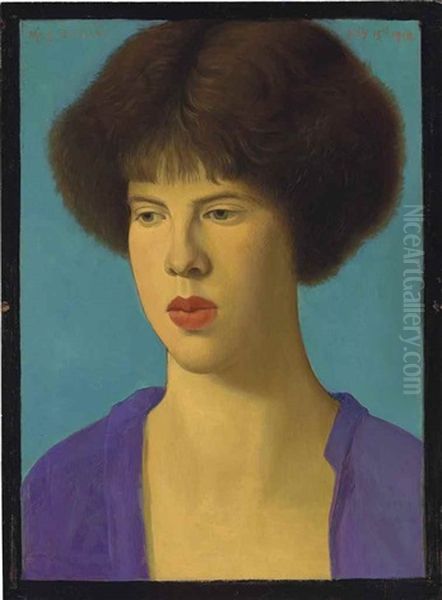

His subject matter often focused on the human figure, particularly portraits and nudes, as well as richly composed still lifes. He frequently painted members of his family, especially his mother, capturing their presence with both intimacy and a powerful monumentality. His portraits convey a deep psychological insight, often revealing a sense of inner tension or melancholy in his sitters.

Gertler's use of colour became increasingly bold and non-naturalistic, employed for expressive and decorative effect. His forms were often sculptural, rounded, and simplified, giving his figures and objects a tangible weight and presence. This move towards stylization and intense expression marked him as a key figure in British modernism, distinct from the more abstract tendencies of Vorticism, though sharing a similar energy.

Key Relationships: Patronage and Passion

Gertler's striking talent and personality attracted influential patrons and friends. Lady Ottoline Morrell, a prominent aristocratic patron of the arts and hostess, became an early and important supporter. She introduced him to the Bloomsbury Group, a circle of intellectuals and artists that included Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant. Gertler became a regular visitor to Morrell's Garsington Manor, a hub for artistic and intellectual exchange.

His relationship with the Bloomsbury Group was complex. While he benefited from their connections and intellectual environment, he sometimes felt like an outsider due to his working-class Jewish background. Virginia Woolf, for instance, recorded mixed impressions of him in her diaries, acknowledging his talent but also commenting on his perceived intensity and ego.

Another significant early patron was Edward Marsh, a civil servant, patron of the arts, and editor of the Georgian Poetry anthologies. Marsh provided financial support and encouragement, purchasing Gertler's work. However, their relationship soured during World War I due to Gertler's staunch pacifism, which clashed with Marsh's patriotic views. Gertler felt the constraints of patronage conflicted with his independence, leading to a break in 1916.

Perhaps the most profound and tumultuous relationship of Gertler's life was with the artist Dora Carrington. They met at the Slade, and Gertler fell deeply in love with her. For several years, he pursued her intensely, but Carrington, while fond of him, could not fully reciprocate his romantic feelings and was exploring her own complex sexuality. Her eventual deep attachment to the homosexual writer Lytton Strachey devastated Gertler. This unrequited love affair caused him immense emotional pain and is often seen as casting a long shadow over his life and art.

The War Years and Merry-Go-Round

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 profoundly affected Gertler. As a committed pacifist, he was horrified by the conflict and determined not to participate in the fighting. He registered as a conscientious objector, a stance that required him to argue his case before tribunals and potentially face imprisonment, though his ill health eventually played a role in his exemption from combat service.

His feelings about the war found their most powerful expression in his masterpiece, Merry-Go-Round, painted in 1916. This large, disturbing canvas depicts figures, some in military uniform, trapped on a garishly coloured, relentlessly turning carousel. The figures, with their mask-like faces and rigid postures, seem locked in a cycle of mechanized, dehumanizing motion. The painting is widely interpreted as a visceral allegory for the futility and horror of modern warfare, a critique of nationalism and militarism.

When Merry-Go-Round was first exhibited with the London Group in 1917, it caused a sensation and considerable controversy. Some critics were shocked by its harshness and perceived crudeness, while others recognized its power and originality. The writer D.H. Lawrence, a friend of Gertler's, famously described it as "the best modern picture I have seen," praising its terrifying depiction of mechanization and the loss of individuality. The painting remains one of the most iconic British artworks of the World War I era and is now housed in the Tate collection.

Mid-Career: Consolidation and Challenges

Throughout the late 1910s and 1920s, Gertler continued to develop his distinctive style, producing powerful portraits, nudes, and increasingly elaborate still lifes. Works like Gilbert Cannan and his Mill (c. 1916), depicting the writer Gilbert Cannan (who was briefly married to Lady Ottoline Morrell's former lover, Mary Ansell), showcase his bold, anti-naturalistic approach and vibrant colour palette. His portrait The Artist's Mother (c. 1922) is a moving and monumental depiction, blending realism with stylized form.

He exhibited regularly, primarily with the London Group and at the Goupil Gallery. Despite critical recognition, financial security remained elusive. Gertler struggled to sell his work consistently, partly due to his uncompromising artistic vision and perhaps his difficult personality. He supplemented his income by teaching, holding a position at Westminster School of Art from 1930.

His personal life continued to be marked by challenges. The emotional scars from the relationship with Carrington lingered. In 1930, Gertler married Marjorie Greatorex Hodgkinson, and the couple had a son, Luke, in 1932. While the marriage provided some stability, it did not resolve his underlying struggles with depression and anxiety.

Health Issues and Declining Years

Compounding his emotional and financial difficulties were persistent health problems. Gertler suffered from tuberculosis, a disease that plagued him intermittently throughout his adult life. He was first diagnosed in 1920 and spent periods convalescing in sanatoriums, including Mundesley Sanatorium in Norfolk in 1929 and again in 1934 and 1936. These bouts of illness interrupted his work and contributed to his recurring bouts of depression.

His artistic style underwent some shifts in his later years. While still committed to figurative painting, some works from the 1930s show a slight softening of his earlier, more aggressive style, perhaps reflecting a search for tranquility amidst his personal turmoil. His still lifes remained a constant, often featuring vibrant arrangements of fruit and flowers, sometimes imbued with a melancholic air, such as Still Life with Bust (1936).

Despite periods of illness, he continued to paint and exhibit. He had several solo shows at the Leicester Galleries in London during the 1930s. However, the rise of abstract art and Surrealism in the 1930s perhaps made his intensely personal figurative style seem less fashionable to some critics and collectors. He felt increasingly isolated and despondent about his career prospects and his health.

Final Act and Immediate Impact

The cumulative pressures of ill health, financial worries, recurring depression, and perhaps a sense of artistic isolation proved overwhelming. Mark Gertler had attempted suicide previously. On June 23, 1939, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, he succeeded in taking his own life in his studio in Highgate, London. He died by gas poisoning at the age of 47.

His death sent shockwaves through the London art world. It was widely regarded as a tragic loss of a major talent. Friends and contemporaries mourned the passing of a painter whose work, despite its sometimes challenging nature, possessed undeniable power and integrity. His suicide highlighted the often-precarious existence of artists and the devastating impact of mental health struggles, issues that resonated deeply within the artistic community.

The timing of his death, just before the world plunged into another global conflict, added another layer of poignancy. The anti-war sentiment expressed so powerfully in Merry-Go-Round seemed tragically prescient. His passing marked the end of a unique voice in British art, one that had grappled intensely with the complexities of modern life, personal identity, and artistic expression.

Legacy and Reappraisal

In the decades following his death, Mark Gertler's reputation has undergone periods of reappraisal. While perhaps never achieving the household name status of some contemporaries like Stanley Spencer, his importance within the narrative of 20th-century British art is now firmly established. Major retrospectives and focused exhibitions have brought his work to new audiences and critical attention.

His paintings are held in numerous public collections, including Tate Britain, the National Portrait Gallery, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and Leeds Art Gallery, ensuring his work remains accessible. The enduring power of Merry-Go-Round guarantees its place in discussions of modern British art and the artistic response to war. His portraits and still lifes are admired for their technical skill, emotional depth, and distinctive stylistic fusion.

Art historians recognize Gertler as a key figure bridging the gap between the Edwardian era and the full emergence of modernism in Britain. His ability to synthesize European avant-garde influences with a deeply personal, often autobiographical, vision remains compelling. His exploration of his Jewish identity, his working-class roots, and his complex emotional life through his art provides rich ground for interpretation.

The market for his work has also remained strong, with significant pieces achieving high prices at auction, such as the sale of The Violinist in 2015. This indicates a sustained collector interest that complements his critical standing. Gertler's life story, marked by early promise, intense relationships, artistic struggle, and ultimate tragedy, continues to fascinate, offering a poignant case study of the interplay between creative genius and personal adversity.

Conclusion: An Enduring Intensity

Mark Gertler's contribution to British art lies in his unwavering commitment to a personal vision, expressed through a powerful and distinctive visual language. He navigated the complex currents of early 20th-century modernism, absorbing influences from artists like Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso, yet forging a path uniquely his own. His work is characterized by its emotional intensity, bold use of colour and form, and profound engagement with the human condition.

From the vibrant streets of Spitalfields to the heart of the London avant-garde and the Bloomsbury circle, Gertler's life was one of contrasts and struggles – poverty and patronage, passion and rejection, critical acclaim and financial hardship, artistic creation and debilitating illness. These experiences are deeply embedded in his art, giving it a raw honesty and enduring power. Though his life ended tragically, Mark Gertler left behind a body of work that continues to command attention, securing his place as one of the most compelling and significant British painters of his generation.