Introduction: A Pillar of Polish Art

Leon Wyczółkowski stands as one of the most significant and versatile figures in the history of Polish art. Flourishing during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period of immense cultural and national significance for Poland, Wyczółkowski navigated the currents of Realism, Impressionism, and Symbolism, forging a unique artistic identity. Primarily celebrated as a painter and printmaker, his prolific output encompassed breathtaking landscapes, insightful portraits, evocative still lifes, and scenes of rural life. He was a leading representative of the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement, an artistic and literary current that sought to revive Polish culture and national spirit during a time when Poland was partitioned and did not exist as an independent state. His dedication to capturing the essence of his homeland, combined with his technical mastery across various media, cemented his legacy as a cornerstone of Polish artistic heritage.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on April 11, 1852, in Huta Miastkowska near Siedlce in eastern Poland, Leon Wyczółkowski's artistic journey began relatively early. From 1869 to 1875, he received foundational training in Warsaw at the Drawing Class (Klasa Rysunkowa). There, he studied under influential figures such as Rafał Hadziewicz and Aleksander Kamiński, but it was Wojciech Gerson who arguably had the most profound impact on the young artist. Gerson, a prominent Polish painter himself and a proponent of Realism imbued with patriotic sentiment, instilled in Wyczółkowski a respect for meticulous observation and the belief in art's higher, national purpose. This early grounding in Realism would remain a constant, albeit evolving, element throughout Wyczółkowski's career.

Seeking broader horizons, Wyczółkowski traveled to Munich in 1875, a major European art center at the time. He briefly attended the Academy of Fine Arts, studying under the Hungarian painter Alexander von Wagner. Munich exposed him to different artistic trends, particularly the dark palette and detailed realism popular among German artists. However, his stay was relatively short, and he soon moved to Kraków, the historical and cultural heart of Poland.

From 1877 to 1879, Wyczółkowski enrolled at the Kraków School of Fine Arts (later Academy). This period was crucial, as he studied under the tutelage of Jan Matejko, the undisputed master of Polish historical painting. Matejko's monumental canvases, depicting glorious moments from Poland's past, dominated the artistic landscape. While Wyczółkowski absorbed Matejko's emphasis on historical themes and national duty, he gradually found himself drawn towards different modes of expression, moving away from the grand historical narratives favored by his teacher. His time in Kraków also exposed him to emerging trends and a vibrant community of artists who would shape the future of Polish art.

The Embrace of Realism and Impressionistic Light

Following his formal education, Wyczółkowski spent time in Warsaw and Lviv before embarking on a pivotal journey to Paris in 1889. The French capital was the epicenter of artistic innovation, particularly Impressionism. While in Paris, he encountered the works of Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas. He was also exposed to the Barbizon School's approach to landscape painting, which emphasized direct observation of nature. Although initially somewhat resistant, the French experience, particularly the Impressionists' fascination with light and color, left an indelible mark on his artistic vision.

Upon returning, Wyczółkowski increasingly turned his attention to landscape and genre scenes, particularly those depicting the rural life and landscapes of Poland and, significantly, Ukraine. His style began to integrate the lessons learned abroad. He adopted a brighter palette and looser brushwork, characteristic of Impressionism, focusing on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. However, he never fully abandoned the solid drawing and compositional structure rooted in his Realist training under Gerson.

This fusion is evident in works from the late 1880s and early 1890s. Paintings like Ploughing in Ukraine (Orka na Ukrainie, c. 1892) and Fishermen (Rybacy, c. 1891) showcase his ability to render scenes of peasant labor with authenticity and empathy, while simultaneously experimenting with vibrant color and the play of sunlight. Beet Root Digging (Kopanie buraków, 1893) is another powerful example, depicting peasants toiling in the fields under a vast sky, rendered with a sensitivity to both the human condition and the atmospheric conditions. He captured the physicality of labor and the specific quality of light on the Ukrainian plains.

Journeys and Inspirations: The Ukrainian Period

Wyczółkowski's connection with Ukraine was particularly profound and resulted in some of his most celebrated works. Between 1883 and 1894, he frequently visited and lived in Ukraine, captivated by its vast landscapes, rich folk culture, and the quality of its light. This period is often considered one of the high points of his career, where his unique blend of Realism and Impressionism reached full maturity.

He painted the steppes, the fields, the Dnieper River, and the daily lives of Ukrainian peasants with remarkable sensitivity. Works like Driving the Ass (1892) or scenes depicting oxen ploughing under the expansive Ukrainian sky are imbued with a sense of place and atmosphere. He was fascinated by the strong sunlight and vibrant colors of the region, which allowed him to push his Impressionistic experiments further. His Ukrainian landscapes are not mere topographical records; they convey a deep emotional connection to the land and its people.

His time in Ukraine provided him with endless subject matter – from the hard labor of the fields to moments of quiet contemplation, from bustling village scenes to solitary figures against the horizon. This period solidified his reputation as a master landscapist and a keen observer of rural life, distinct from the historical epics of Matejko or the purely academic styles prevalent earlier. His Ukrainian works resonated deeply within Poland, offering visions of a shared Slavic heritage and the beauty of the common folk.

The Symbolist Turn and Penetrating Portraiture

While Realism and Impressionism formed the bedrock of his style, Wyczółkowski's art also embraced Symbolism, particularly around the turn of the century, coinciding with the rise of the Young Poland movement. This artistic and literary trend emphasized individualism, emotional expression, and the exploration of national myths, legends, and spiritual themes. Wyczółkowski's engagement with Symbolism was perhaps less overt than that of contemporaries like Jacek Malczewski or Stanisław Wyspiański, but it added layers of meaning and mood to his work.

His Symbolist tendencies are visible in certain landscapes, where nature takes on a deeper, almost mystical quality. Trees, rocks, and water are sometimes imbued with anthropomorphic or spiritual significance. Works depicting the ancient Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, such as Christ at Wawel Cathedral (also known as the Wawel Crucifix), blend historical reverence with a palpable sense of mystery and spiritual weight. The cross became a recurring motif, representing faith, suffering, and national martyrdom, linking Poland's history with its Catholic identity. His association with the artist and later saint, Adam Chmielowski (Brother Albert), a key figure in Polish religious and artistic life, likely reinforced these spiritual dimensions in his work.

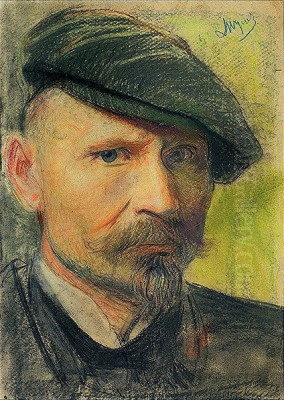

Wyczółkowski was also a highly accomplished portraitist. His portraits moved beyond mere likeness to capture the psychological essence of his sitters. He painted many prominent figures of his time, including writers, artists, and intellectuals. His 1904 portrait of the writer Stefan Żeromski, a leading figure of the Young Poland era, is a prime example. Rendered with sensitivity, it conveys the subject's intellectual intensity and perhaps a hint of melancholy. His portraits often employed sophisticated lighting and compositional strategies, sometimes incorporating elements of the sitter's profession or personality into the background, adding further layers of meaning. He utilized various techniques, including oil and pastel, adapting his approach to suit the individual subject.

Mastery of Diverse Media: Pastel and Printmaking

Leon Wyczółkowski's technical virtuosity extended beyond oil painting. He was a master of multiple media, demonstrating remarkable skill in pastel, watercolour, drawing, and various printmaking techniques. As he grew older, particularly after 1900, he showed an increasing preference for pastels. This medium allowed him to work quickly and capture subtle nuances of light and color with a delicate, powdery texture.

His pastel works, often depicting flowers, landscapes, and portraits, possess a unique luminosity and freshness. Study of Roses II (1890) showcases his early command of the medium, capturing the delicate texture and vibrant color of the flowers. His later pastels, especially those of the Tatra Mountains or forest interiors, achieve remarkable atmospheric effects, blending precision with a soft, evocative quality. The immediacy of pastel suited his Impressionistic sensibility, allowing him to record fleeting moments and light conditions directly.

Furthermore, Wyczółkowski made significant contributions to the revival of artistic printmaking in Poland. He experimented extensively with etching, lithography, and algraphy. His graphic works often revisited themes from his paintings but explored them through the unique possibilities of line, tone, and texture offered by printmaking. Notable examples include his lithographic series depicting the architecture of Gdańsk, Warsaw, and Lublin, as well as his evocative etchings in the Impressions from the Baltic Sea series. His prints were not mere reproductions but original artistic statements, demonstrating his deep understanding of graphic processes. His dedication to printmaking helped elevate its status as a fine art form in Poland.

Japonisme and the Elegance of Still Life

Like many European artists at the turn of the century, Wyczółkowski was fascinated by Japanese art, a phenomenon known as Japonisme. This interest was significantly fueled by his friendship with Feliks "Manggha" Jasieński, a prominent critic and collector of Japanese art whose extensive collection would later form the basis of the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology in Kraków. Jasieński's enthusiasm and collection provided Wyczółkowski with direct access to Japanese prints (ukiyo-e), ceramics, and textiles.

The influence of Japanese aesthetics is discernible in Wyczółkowski's work, particularly in his still lifes and flower studies, but also in his approach to composition and perspective in some landscapes. He admired the bold compositions, flattened perspectives, decorative patterns, and calligraphic lines found in Japanese prints. This influence can be seen in the way he arranged objects in his still lifes, often employing asymmetrical compositions and focusing on the inherent beauty of form and color.

His still lifes, especially those featuring flowers, porcelain, or arrangements of objects against decorative fabrics, became a significant part of his oeuvre. He treated these subjects with the same seriousness and artistic rigor as his landscapes or portraits. Works featuring chrysanthemums, roses, or peonies showcase his exquisite sensitivity to color, texture, and light, often combined with compositional principles subtly borrowed from Japanese art. His collaboration and discussions with Jasieński were instrumental in developing this aspect of his art, making him a master of the still life genre in Polish art.

The Young Poland Movement and Contemporaries

Leon Wyczółkowski was a central figure in the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement, which dominated Polish cultural life from roughly 1890 to 1918. This movement, analogous to Art Nouveau and Symbolism elsewhere in Europe, sought artistic renewal and the expression of a modern Polish identity, often drawing inspiration from folklore, nature, history, and psychology. Wyczółkowski embodied many of its ideals: a commitment to artistic excellence, an interest in diverse techniques, a deep connection to Polish landscape and culture, and an exploration of mood and symbolism.

He was closely associated with other leading artists of the movement. Besides his teacher Matejko and influences like Gerson and Chmielowski, his contemporaries included the Symbolist painters Jacek Malczewski and Stanisław Wyspiański (who was also a playwright and designer), the Impressionist-influenced Józef Pankiewicz, and fellow professor at the Kraków Academy, Józef Mehoffer, known for his stained glass and paintings. He also interacted with painters like Wojciech Kossak, known for historical and military scenes.

Wyczółkowski was a co-founder and active member of the "Sztuka" (Art) Society of Polish Artists, established in Kraków in 1897. This society aimed to promote high standards in Polish art and organize independent exhibitions, free from the constraints of older academic institutions. "Sztuka" brought together many leading artists of the Young Poland generation, fostering collaboration and dialogue. Wyczółkowski regularly exhibited with the society, contributing significantly to its prestige and influence both within Poland and internationally through exhibitions held abroad. His involvement underscored his commitment to the collective advancement of Polish art during this vibrant period.

Academic Career and Lasting Influence

Beyond his prolific artistic output, Leon Wyczółkowski played a crucial role in shaping the next generation of Polish artists through his teaching career. In 1895, he was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, a position he held until 1911. During his tenure, he taught painting and drawing, influencing numerous students who would go on to become significant artists in their own right. His teaching methods likely reflected his own artistic evolution, emphasizing solid draftsmanship alongside an appreciation for color, light, and direct observation of nature.

His influence extended beyond Kraków. Later in his career, from 1934 until his death, he served as a professor and head of the Graphic Arts department at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. This appointment acknowledged his mastery and significant contributions to Polish printmaking. His dedication to teaching ensured that his artistic principles and technical knowledge were passed down, contributing to the continuity and development of Polish art in the twentieth century.

His impact as an educator complemented his artistic achievements. He was respected not only for his talent but also for his dedication to his students and his role in the institutional life of Polish art academies. His long career as both a practicing artist and an influential professor solidified his position as a patriarch of modern Polish art, admired by colleagues and students alike.

Later Life, Legacy, and the Bydgoszcz Connection

In his later years, Wyczółkowski continued to work, though his focus shifted more towards pastels and graphic arts. He spent considerable time at his manor house in the village of Gościeradz near Bydgoszcz, which he acquired in 1922. The surrounding landscape, particularly the ancient trees of the Tuchola Forest, provided new inspiration. His connection to the Bydgoszcz region became particularly significant for his legacy.

Recognizing the importance of preserving his artistic heritage, Wyczółkowski made a substantial donation of his works – paintings, drawings, prints, personal memorabilia, and studio equipment – to the city of Bydgoszcz. This generous gift formed the core collection of what would eventually become the Leon Wyczółkowski District Museum (Muzeum Okręgowe im. Leona Wyczółkowskiego w Bydgoszczy). Established formally after his death, this museum remains the most important center for the study and appreciation of his life and work, housing the largest single collection of his art and related archival materials.

Leon Wyczółkowski died in Warsaw on December 27, 1936. He was buried in the village cemetery in Wtelno, near Gościeradz, according to his wishes. His death marked the end of an era for Polish art, but his legacy was firmly secured through his vast body of work, his influence as a teacher, and the dedicated museum in Bydgoszcz. He is also remembered for his advocacy for nature conservation, particularly his efforts that contributed to the protection of the ancient yews in the Wierzchlas reserve, now named in his honor.

Major Collections and Exhibitions

The primary repository for Leon Wyczółkowski's work is the Leon Wyczółkowski District Museum in Bydgoszcz. This institution not only holds a vast collection spanning his entire career and all media but also actively researches and promotes his legacy through permanent and temporary exhibitions, publications, and educational programs. It offers an unparalleled insight into his artistic world, including reconstructions of his living and working spaces.

Significant collections of his work are also held by Poland's major national museums. The National Museum in Kraków, where Wyczółkowski spent much of his formative and professional life, possesses numerous important paintings, pastels, and prints. The National Museum in Warsaw also holds key works, including the famous Girl from the Highlands in a Yellow Kerchief (Góralka / Wiejska dziewczyna w żółtej chuście), which was looted during World War II and recovered and returned to the museum in 2020.

Other institutions, such as the Regional Museum in Poznań and the Royal Castle in Warsaw, also hold works by Wyczółkowski and have hosted significant exhibitions dedicated to his art over the years. His works frequently appear in retrospectives of Polish art and thematic exhibitions focusing on Realism, Impressionism, Symbolism, and the Young Poland movement. Furthermore, his paintings and prints are highly sought after by private collectors and regularly achieve high prices at auction, attesting to his enduring market value and artistic importance.

Critical Reception and Enduring Significance

Leon Wyczółkowski is universally acclaimed as one of the giants of Polish art. Academic and critical consensus places him among the most important Polish painters and printmakers of his generation, a key figure bridging the nineteenth-century traditions and the modernism of the twentieth century. His mastery across multiple media – oil, pastel, watercolour, etching, lithography – is widely recognized, as is his exceptional skill as a draftsman and colorist.

He is celebrated for his profound connection to the Polish landscape and his ability to capture its specific character and atmosphere. His depictions of the Tatra Mountains, the Ukrainian steppes, the Baltic coast, and the forests of Poland are considered iconic representations of the national scenery. His sympathetic portrayal of rural life and labor resonated deeply within a society grappling with issues of national identity and social change. His contributions to portraiture and still life are also highly valued.

While overwhelmingly positive, some critical discussions might touch upon perceived limitations. Occasionally, commentators might suggest that his focus remained largely within the established genres of landscape, portrait, and still life, perhaps engaging less directly with radical avant-garde experiments than some of his European contemporaries. Some might argue that certain works prioritize technical brilliance or formal concerns over deeper social or political commentary, although his connection to the national spirit via landscape and history is undeniable. These minor points, however, do little to diminish his overall stature.

His legacy endures through his vast artistic output, preserved in major museums, and through the continued appreciation of his unique synthesis of Realism, Impressionism, and Symbolism, all filtered through a distinctly Polish sensibility. He remains a beloved figure in Polish culture, representing a period of great artistic vitality and national aspiration.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Leon Wyczółkowski's career spanned a dynamic period in Polish and European art history. From his early training under the masters of Polish Realism and historical painting like Gerson and Matejko, through his absorption of French Impressionism, to his mature engagement with Symbolism and the ideals of the Young Poland movement, he forged a path that was both deeply personal and profoundly influential. His sensitivity to light and color, his technical versatility, and his deep love for the landscapes and people of Poland and Ukraine resulted in a body of work that continues to captivate viewers.

As a painter, printmaker, and educator, Wyczółkowski left an indelible mark on Polish culture. His ability to convey the beauty of nature, the dignity of labor, the psychology of individuals, and the subtle moods of Symbolism secured his place in the pantheon of Polish art. Through institutions like the dedicated museum in Bydgoszcz and the presence of his works in national collections, the enduring vision of Leon Wyczółkowski remains accessible, continuing to inspire and enrich our understanding of Polish art history.