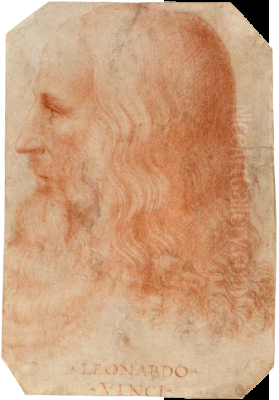

Leonardo da Vinci stands as perhaps the most iconic figure of the Italian Renaissance, a man whose boundless curiosity and extraordinary talents bridged the worlds of art and science. Born Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci on April 15, 1452, in the small Tuscan town of Vinci, he was the illegitimate son of a local notary, Ser Piero da Vinci, and a peasant woman named Caterina. Despite the circumstances of his birth, his potential was recognized early on. He passed away in Amboise, France, on May 2, 1519, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire awe and fascination centuries later. His life and work embody the very essence of the "Renaissance Man" – a polymath whose genius illuminated numerous fields.

Early Life and Florentine Apprenticeship

Leonardo spent his formative years in the vibrant artistic crucible of 15th-century Florence. Around the age of 14 or 15, he was apprenticed to Andrea del Verrocchio, one of the city's leading artists. Verrocchio's workshop was a bustling center of creativity, producing not only paintings but also sculptures, goldsmith work, and decorative arts. This environment provided Leonardo with a comprehensive education in artistic techniques and craftsmanship.

In Verrocchio's studio, Leonardo learned painting, sculpture, drafting, mechanics, and chemistry. He worked alongside other talented apprentices and collaborators, including Sandro Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, and Lorenzo di Credi. Even in these early years, Leonardo's exceptional talent began to shine. Giorgio Vasari, the famed 16th-century biographer of artists, recounts the story of Leonardo painting an angel in Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ with such skill that the master supposedly resolved never to paint again. While likely apocryphal, the tale highlights Leonardo's rapidly developing prowess. His early independent works, such as the Annunciation, already display his keen observation of nature and his developing mastery of light and shadow.

The Milanese Period: Art and Science Flourish

Around 1482, seeking new opportunities, Leonardo moved to Milan to enter the service of Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. He presented himself not primarily as a painter, but as a military engineer, architect, sculptor, and musician, showcasing the breadth of his interests and abilities. He remained in Milan for nearly two decades, a period of intense activity and remarkable creativity.

During his time at the Sforza court, Leonardo undertook numerous projects. He worked on designs for a massive bronze equestrian statue honoring Ludovico's father, Francesco Sforza, a project that ultimately remained unrealized due to political upheaval and war. He also served as a court artist, painting portraits, designing festivals, and creating stage sets. Two of his most celebrated paintings date from this period: the haunting Virgin of the Rocks (two versions exist) and the iconic Lady with an Ermine, a portrait of Ludovico's mistress, Cecilia Gallerani.

It was also in Milan that Leonardo painted one of the cornerstones of Western art, The Last Supper. Commissioned for the refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery, this monumental mural depicts the dramatic moment when Christ announces that one of his apostles will betray him. Leonardo experimented with a tempera and oil medium on dry plaster, rather than traditional fresco, which unfortunately led to the painting's rapid deterioration. Despite its fragile condition, the work's powerful composition, psychological depth, and masterful portrayal of human emotion remain profoundly impactful.

Beyond painting, Leonardo's scientific and engineering pursuits flourished in Milan. He filled notebooks with detailed drawings and observations on anatomy, botany, geology, hydraulics, mechanics, and flight. He established a workshop where he trained students and collaborators, including Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio and Marco d'Oggiono, beginning the lineage of artists known as the "Leonardeschi."

Wanderings: Florence, Rome, and Beyond

Following the fall of Ludovico Sforza in 1499, Leonardo left Milan. The subsequent years saw him travel and work in various Italian cities, including Venice, Mantua, and eventually back to Florence. His return to Florence around 1500 placed him in direct competition with another rising giant of the Renaissance: Michelangelo.

This rivalry famously culminated in commissions for large battle murals in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence's town hall. Leonardo was tasked with painting the Battle of Anghiari, while Michelangelo was commissioned for the Battle of Cascina. Neither work was completed, and only preparatory studies and copies survive, yet they represent a fascinating clash of artistic titans – Leonardo's dynamic, swirling chaos versus Michelangelo's powerful, sculptural nudes.

During this second Florentine period, Leonardo also began work on what would become the world's most famous portrait: the Mona Lisa (La Gioconda), believed to depict Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine merchant. The painting's enigmatic smile, subtle modeling achieved through sfumato (smoky transitions between tones), and lifelike presence have captivated viewers for centuries. He carried the unfinished painting with him for the rest of his life.

Leonardo later spent time in Rome, from 1513 to 1516, under the patronage of Giuliano de' Medici, brother of Pope Leo X. Rome was then the center of artistic activity, dominated by the projects of Michelangelo (Sistine Chapel ceiling) and Raphael (Vatican Stanze). While Leonardo associated with figures like the architect Donato Bramante, his Roman period was less productive artistically compared to his earlier years, focusing more on scientific studies. Raphael, significantly younger than Leonardo but already a celebrated master, had clearly studied Leonardo's Florentine works, absorbing lessons in composition and psychological portrayal evident in his own Madonnas and portraits.

Final Years in France: Legacy Secured

In 1516, at the invitation of King Francis I of France, an admirer of Italian art, Leonardo moved to Amboise. The king appointed him "First Painter, Engineer, and Architect to the King" and provided him with the manor house Clos Lucé, near the royal château. Here, Leonardo spent his final years, primarily organizing his voluminous notebooks and undertaking architectural and engineering projects for the king, such as designs for a new royal palace at Romorantin.

He was accompanied in France by his most loyal pupils, Francesco Melzi and Andrea Salai (Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno). Melzi, a nobleman from Milan, became Leonardo's principal heir and executor, inheriting his manuscripts, drawings, and artistic tools. Salai, who had entered Leonardo's household as a boy and remained a companion for decades, also received a significant inheritance, including, according to some interpretations of documents, paintings possibly including the Mona Lisa at one point. Leonardo's health declined in these later years, possibly due to a stroke affecting his right hand, though he continued to draw and write with his left. He died at Clos Lucé on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67.

The Artist: Techniques and Masterpieces

Leonardo's artistic output, though relatively small compared to other Renaissance masters (only about 15-20 paintings are generally attributed to him), is characterized by profound innovation and technical mastery. He revolutionized painting through his development of sfumato, a technique using subtle gradations of tone and color to blur sharp outlines and create soft, atmospheric effects. This allowed for unprecedented realism and psychological depth, particularly visible in the Mona Lisa's elusive expression and the atmospheric landscapes of the Virgin of the Rocks.

He also mastered chiaroscuro, the use of strong contrasts between light and dark, to model forms and create dramatic tension, as powerfully demonstrated in The Last Supper and Saint John the Baptist. His compositions were carefully constructed, often employing geometric principles like the pyramid structure seen in Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, to achieve balance and harmony while conveying complex emotional and narrative content.

Beyond the aforementioned masterpieces, other significant works include the early Annunciation, the unfinished but intensely expressive Adoration of the Magi and Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, the captivating Lady with an Ermine, and the late, ambiguous Saint John the Baptist. Each work reveals his meticulous attention to detail, his deep understanding of human anatomy and psychology, and his ability to infuse traditional religious and secular subjects with new life and meaning.

The Scientist and Inventor: An Insatiable Curiosity

Leonardo's art was inextricably linked to his scientific investigations. He believed that sight was the noblest sense and that painting was a science, demanding a deep understanding of the natural world. His notebooks, thousands of pages filled with drawings and notes (often written in his characteristic mirror script, from right to left), attest to the astonishing range of his inquiries.

He conducted detailed anatomical studies, dissecting human and animal bodies to understand the structure of bones, muscles, and organs. His anatomical drawings were centuries ahead of their time in their accuracy and clarity, revealing his insights into the workings of the heart, the nervous system, and the growth of a fetus in the womb. These studies directly informed the lifelike figures in his paintings.

His fascination extended to botany, geology, hydraulics, and optics. He studied the structure of plants, the formation of rocks and river valleys, the movement of water, and the nature of light and shadow. He was a visionary inventor, sketching designs for machines that anticipated later technologies, including a helicopter-like flying machine, an armored tank, a diving suit, and various hydraulic devices. While most of these inventions were never built, they demonstrate his remarkable mechanical ingenuity and forward-thinking mind. His love for animals was also notable; he studied their movement and anatomy, expressed dismay at human cruelty towards them, and was reportedly a vegetarian.

Students and the Leonardeschi

Leonardo maintained an active workshop throughout much of his career, attracting numerous students and followers who were captivated by his style and ideas. These artists, known collectively as the "Leonardeschi," played a crucial role in disseminating his artistic innovations, particularly in Lombardy.

Francesco Melzi stands out as the most devoted disciple, meticulously preserving Leonardo's notebooks and compiling parts of them into the Treatise on Painting (Codex Urbinas), which helped spread Leonardo's theories. Melzi's own paintings closely emulate the master's soft style. Andrea Salai, though perhaps less artistically gifted, was a long-term presence in the workshop and likely assisted Leonardo on various projects.

Other notable followers include Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, known for his sensitive portraits; Andrea Solario; Bernardino Luini, whose popular works adapted Leonardo's style with a sweet, devotional quality; and Marco d'Oggiono, who produced numerous copies of Leonardo's compositions, including The Last Supper. The influence extended beyond direct pupils; artists like Andrea del Sarto in Florence and even the Venetian master Giorgione show traces of Leonardo's sfumato and compositional ideas. The Leonardesque style, characterized by its smoky modeling, gentle expressions, and complex compositions, became a dominant force in Milanese art for decades.

Anecdotes, Mysteries, and Controversies

Leonardo's life and work are shrouded in a degree of mystery and have generated numerous anecdotes and controversies. His parentage and the identity of his mother remain subjects of speculation, with some theories suggesting she may have had Middle Eastern origins. His tendency to leave works unfinished, such as the Adoration of the Magi and the Battle of Anghiari, has been attributed to his perfectionism, his easily distracted curiosity, or his restless movement between projects and patrons.

His personal life also invites intrigue. He never married and had no children. An accusation of sodomy leveled against him and others in Florence in 1476 was dismissed, but it fueled centuries of speculation about his sexuality. His close relationships with his male pupils, particularly Salai and Melzi, have been interpreted by some as romantic, though conclusive evidence is lacking. His use of mirror writing in his notebooks is often seen as an attempt to keep his ideas secret, although it might simply have been easier for him as a left-hander.

The attribution of works to Leonardo remains a contentious field. Given his limited output and the prevalence of workshop copies and imitations, definitively assigning paintings to his hand can be challenging. The recent case of the Salvator Mundi, which sold for a record price amid ongoing debates about its authenticity and condition, exemplifies these difficulties. Even established masterpieces like The Last Supper present challenges due to their poor state of preservation, making it difficult to fully appreciate their original appearance. His unconventional approach to fulfilling commissions sometimes led to disputes with patrons.

Rivalries and Relationships

The Italian Renaissance was a period of intense competition as well as collaboration among artists. Leonardo's interactions with his contemporaries shaped his career and the artistic landscape. His relationship with Andrea del Verrocchio evolved from master-apprentice to collaborator, though Leonardo soon surpassed his teacher. He maintained connections with fellow Florentines like Botticelli and Perugino.

His most famous rivalry was undoubtedly with Michelangelo. Twenty-three years younger, Michelangelo represented a different artistic temperament – passionate, focused primarily on the human form, and deeply rooted in sculpture. Their personalities clashed: Leonardo was elegant, sociable, and scientifically inclined; Michelangelo was solitary, intense, and devoutly focused on his art. Their competition for the Palazzo Vecchio murals was a public manifestation of their differing artistic visions. Vasari records instances of sharp verbal exchanges between them.

In contrast, Leonardo's influence on Raphael was more one-sided. Raphael, arriving in Florence around 1504, eagerly studied the works of both Leonardo and Michelangelo. He adopted Leonardo's pyramidal compositions, sfumato technique, and psychological nuance, integrating them into his own harmonious and graceful style, particularly evident in his Madonnas. While influenced, Raphael developed his own distinct artistic identity, becoming the third pillar of the High Renaissance alongside the two older masters. Leonardo also interacted with architects like Bramante during his time in Milan and Rome.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Leonardo da Vinci occupies a unique and towering position in the history of Western culture. He is the archetype of the Renaissance Man, demonstrating that art and science are not separate domains but complementary ways of understanding the world. His relentless curiosity drove him to explore the mysteries of nature and the human body with unparalleled depth and precision.

His artistic innovations fundamentally changed the course of painting. Sfumato and chiaroscuro, combined with his understanding of anatomy, perspective, and human emotion, created a new standard of realism and psychological complexity. Masterpieces like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper are not merely famous paintings; they are cultural touchstones, endlessly reproduced, analyzed, and reinterpreted.

His scientific notebooks reveal a mind centuries ahead of its time, filled with insights and inventions that anticipated later discoveries. Though largely unpublished during his lifetime, they represent an extraordinary testament to the power of observation and empirical investigation. Francesco Melzi's efforts to preserve and organize these notes ensured that at least some of Leonardo's theoretical knowledge could influence later generations.

Beyond his specific achievements, Leonardo's enduring legacy lies in his holistic approach to knowledge and creativity. He showed how keen observation, rigorous analysis, and imaginative synthesis could lead to profound insights in any field. His life and work continue to inspire artists, scientists, engineers, and thinkers, reminding us of the boundless potential of the human mind.

Conclusion

Leonardo da Vinci was more than a painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist, and writer; he was a phenomenon. His ability to excel across such a vast range of disciplines remains unparalleled. From the enigmatic smile of the Mona Lisa to the intricate anatomical drawings and visionary machine designs, his work reflects a profound engagement with the world in all its complexity. He sought to understand the fundamental principles governing nature and human existence, and through his art and science, he left an indelible mark on human civilization, forever embodying the spirit of the Renaissance and the enduring power of human curiosity and genius.